Pericles indeed, by his rank, ability, and known integrity, was enabled to exercise an independent control over the multitude—in short, to lead them instead of being led by them; for as he never sought power by improper means, he was never compelled to flatter them, but, on the contrary, enjoyed so high an estimation that he could afford to anger them by contradiction. Whenever he saw them unseasonably and insolently elated, he would with a word reduce them to alarm; on the other hand, if they fell victims to a panic, he could at once restore them to confidence. In short, what was nominally a democracy became in his hands government by the first citizen. Thucydides - History of the Peloponnesian War, Book II

Pericles or Perikles (ca. 495 BC-429 BC, Greek: Περικλῆς, Περικλής, meaning "surrounded by glory") was a prominent and influential statesman, orator and general of Athens during the city's Golden Age (specifically, between the Persian and Peloponnesian wars). He was a descendant of the renowned Alcmaeonidae family.

Pericles had such a profound influence on Athenian society that Thucydides acclaimed him as "the first citizen of Athens". As a result of his efficient governance of Athens, the period from 461 BC to 429 BC is sometimes known as "The Age of Pericles" (Though this terminology can extend to as late as 379 BC).

Pericles promoted arts and literature and his work contributed to Athens achieving its reputation as the educational and cultural centre of the Greek world. Eager to reinforce Athenian intellectual prowess, he prompted an ambitious building project that included most of the surviving structures on the Acropolis (including the Parthenon). Furthermore, Pericles fostered the blossoming of democracy, to such an extent that critics label him as a populist.[1]

Early years

Pericles was born in 495 BC[α] in the deme of Cholargos (modern day Kamatero or Peristeri), just north of Athens. He was the son of the politician Xanthippus, under whose leadership Athens had won in Mycale in 479 BC, though he had been ostracized only five years before. Pericles' mother, Agariste, was the offspring of the noble though controversial family of the Alcmaeonids. It was this dynastic marriage that boosted Xanthippus' political career. Agariste was the great-granddaughter of the tyrant of Sicyon Cleisthenes and the niece of the Athenian reformer Cleisthenes,[β] also belonging to the Alcmaeonidae family.[2] According to Herodotus[3] and Plutarch,[4] a few days before Pericles' birth, Agariste dreamed she bore a lion, an ambivalent symbolism, alluding to the unusual size of Pericles' skull. In fact, the asymmetric dimensions of his head led the comedians of his era to taunt and ridicule him.[4]

|

"We are rather a pattern to others than imitators ourselves. Its administration favors the many instead of the few; this is why it is called a democracy. If we look to the laws, they afford equal justice to all in their private differences; if to social standing, advancement in public life falls to reputation for capacity, class considerations not being allowed to interfere with merit; nor again does poverty bar the way, if a man is able to serve the state, he is not hindered by the obscurity of his condition." Pericles (Funeral Oration, Thucydides, II, 37) |

Pericles belonged to the local tribe of Acamantis (Aκαμαντίδα φυλή) and his early years were quiet. Partly because of his intrinsic introversion, he avoided public appearances, preferring his studies instead.

His family's nobility and wealth allowed him to follow his natural inclination toward education. He learned music from the masters (Damon[5] or Pythocleides[6]) and he is considered to be the first politician to attribute great importance to philosophy. He enjoyed the society of Zeno of Elea and Anaxagoras,[5] who became a close friend and influence on him. Pericles' thinking and rhetorical charisma are due partly to the philosopher’s teaching of emotional calm in the face of trouble as well as skepticism about divine phenomena.[2] His proverbial calmness and self-control are also regarded as resulting from the philosopher’s influence.[7]

His political career until 431 BC

Entering politics

If his long political career lasted more than 40 years,[8] Pericles must have entered politics about 469 BC. During all these years he endeavored to protect his privacy and to stand as a model for his compatriots. For example, he would often avoid banquets, trying to be frugal.[9]

According to tradition, Pericles made his first political appearance in 463 BC.[10] He was the leading prosecutor against Cimon, the head of the conservative party, who was accused of neglecting Athens' vital interests in Macedonia. Although Cimon was acquitted,[11] this confrontation proved that Pericles' major opponent was vulnerable.

Ostracizing Cimon

Around 462 BC-461 BC[12] the leadership of the democratic party considered it was time to take aim at Areios Pagos, which was controlled by the Athenian aristocracy. The leader of the party and mentor of Pericles, Ephialtes, proposed the shrinking of Areios Pagos’ powers. Ecclesia adopted Ephialtes' proposal without strong opposition.[13] This reform signaled the commencement of a new era of "radical democracy".[12] The democratic party gradually became dominant in Athenian politics and Pericles seemed willing to follow a populist policy in order to cajole the public. His stance can be explained by the fact that his main opponent, Cimon, was rich and generous, having no problem to donate large chunks of his fortune. In 461 BC, Pericles achieved the political elimination of his formidable opponent, using the weapon of ostracism. The ostensible accusation was that Cimon betrayed his city, acting as a friend of Sparta,[14] an accusation usually attached to the members of the conservative party.

Even after Cimon's ostracism, Pericles continued to espouse and promote a populist social policy, that is, one pleasing to the people.[13] He first proposed a decree, according to which the poor could watch theatrical plays without paying, as the state would reimburse the equivalent price. By other decrees he lowered the property requirement for the archonship (458 BC-457 BC)[15] and bestowed generous wages to all the citizens who were participating in the court of Heliaia (Ηλιαία), a reform implemented just after 454 BC[16]. His most controversial measure, however, was a law of 451 BC confining Athenian citizenship to those of Athenian parentage on both sides.[17]

Such measures impelled Pericles' critics to regard him as responsible for the gradual degeneration of the Athenian democracy. One of his prominent critics is the major modern Greek historian, K. Paparrigopoulos. According to Paparrigopoulos' point of view, Pericles sought for the expansion and stabilization of all democratic institutions.[18] Hence, he enacted a legislation enforcing the accession of the lower taxes to the political system and to the public offices. Therefore, Pericles strove to motivate all these social classes, which were previously prohibited by the status quo ante from being more active and from occupying public offices.[19] On the other hand, Cimon's firm conviction was that no further free space for democratic evolution existed. He was definite that democracy had reached its peak and Pericles’ reforms were leading to the stalemate of populism. After so many centuries, it is still extremely difficult to choose between these two conflicting cogitations. According to Paparrigopoulos, history vindicated Cimon, since Athens, after Pericles' death, sunk in the abyss of political turmoil and demagogy. Paparrigopoulos maintains that an unprecedented regression descended upon the city, whose glory perished due to the anterior populist policies of Pericles.[18]

Leading Athens

Ephialtes' murder in 461 BC[γ] paved the way for Pericles to consolidate his authority. Lacking any robust opposition after the expulsion of his most menacing opponent, the unchallengeable leader of the democratic party became the unchallengeable ruler of Athens. He remained in power almost uninterruptedly until his death in 429 BC.

The First Peloponnesian War

Pericles made his first military excursions during the First Peloponnesian War, which was caused in part by Athens' alliance with Megara and Argos and the subsequent reaction of Sparta. In 454 BC he attacked Sicyon and Acarnania.[20] He then unsuccessfully tried to take Oeniadea on the Corinthian gulf, before returning to Athens. In 451 BC, Cimon is said to have returned from exile and negotiated a five years' truce with Sparta after a proposal of Pericles, an event indicating a shift in his initial political philosophy. Pericles may have realized the importance of Cimon's contribution during the ongoing war conflicts against the Peloponnesians and the Persians. Plutarch underlines that Cimon struck a power-sharing deal with his opponent, according to which Pericles would carry through the interior affairs and Cimon would be the leader of the Athenian army, campaigning abroad.[21] If true, this deal constitutes a concession of Pericles that he was not a great strategist. Cimon defeated the Persians in the Battle of Salamis, but died of disease in 449 BC.

In the spring of 449 BC, Pericles proposed the Congress Decree, which led to a meeting ("Congress") of all Greek states in order to consider the question of rebuilding the temples destroyed by the Persians. The Congress failed because of Sparta's stance,[22] but the main question is whether Pericles' real intentions were to prompt some kind of confederation with the participation of all the Greek cities or just to assert Athenian pre-eminence. The second hypothesis seems more realistic, since no sincere and plain panhellenic visions existed during this tense period in Greece. According to T. Buckley, the objective of the Congress Decree was a new mandate for the Delian League and for the collection of "phoros" (taxes).[23]

|

"Remember, too, that if your country has the greatest name in all the world, it is because she never bent before disaster; because she has expended more life and effort in war than any other city, and has won for herself a power greater than any hitherto known, the memory of which will descend to the latest posterity." Pericles (Third Oration, Thucydides, II, 64) |

In 449 BC the Second Sacred War erupted, when Sparta detached Delphi from Phocis and rendered it independent. A year later, Pericles led the Athenian army against Delphi, in order to reinstate Phocis in its former sovereign rights on the oracle of Delphi.[24] In 447 BC Pericles engaged in his most admired excursion,[2] the expulsion of barbarians from the Thracian peninsula of Gallipoli,[25] in order to establish the Athenian population in new land. The major problem for Athens at that time were, however, the revolts of its allies (or of its subjects, to be more accurate). In 447 BC the conservatives of Thebes conspired against the democratic faction. The Athenians demanded the immediate surrender of the oligarchs, but, after their defeat at the Battle of Coronea, Pericles imposed a more moderate stance.[26] In 446 BC, a more dangerous arousal erupted. Euboea and Megara revolted and Pericles crossed over to Euboea with his troops. He was forced however to return, when the army of Sparta invaded Attica. Through briberies [27] and negotiations, Pericles repulsed the imminent threat. It is interesting to point out that, when Pericles was later audited for the handling of public money, an expenditure of 10 talents was not sufficiently justified, since the official documents just referred that the money was spent for a "very serious purpose". Nonetheless, the "serious purpose" (namely the bribery) was so obvious to the auditors that they approved the expenditure without official meddling and without even investigating the mystery.[28] Just after the deliverance of Athens from Sparta's threat, Pericles crossed back to Euboea with 50 ships and 5.000 soldiers, cracking down any opposition. He then inflicted a stringent punishment on the landowners of Chalcis, who lost their properties. The residents of Istiaia, who had butchered the crew of an Athenian trireme, were chastised more harshly, since they were uprooted and replaced by 2.000 Athenian settlers.[28] The arrangement between Sparta and Athens was ratified by the Thirty Years' Peace (winter of 446 BC–445 BC). According to this treaty, Megara was returned to the Peloponnesian League, Troezen and Achaea became independent, Aegina was to be a tributary to Athens but autonomous, and disputes were to be settled by arbitration.

The final battle with the conservatives

In 444 BC, the conservative and the democratic faction confronted each other in a fierce strife. The new ambitious leader of the conservatives, Thucydides, son of Melesias, accused Pericles of profligacy, criticizing the way his political opponent spent the money for the ongoing building plan. Thucydides managed, initially, to incite the passions in ecclesia in his favor, but, when the leader of the democrats took the floor, he put the conservatives in the shade. Pericles responded resolutely and wittily, proposing to reimburse the city for all the expenses from his private property, under the term that he would make the inscriptions of dedication in his own name.[29] His shrewd stance was greeted with applause and Thucydides suffered an unexpected defeat. In 442 BC, the Athenian rabble ostracized Thucydides for 10 years[29] and Pericles remained once again the unchallenged suzerain of the Athenian political arena.

Athens' rule over its alliance

Pericles wanted to stabilize Athens' dominance over its alliance and to enforce its preeminence in Greece. Through various measures, he turned the Delian League into an Athenian empire. In 454 BC, the treasury of the alliance was transferred from Delos to Athens and around 447 BC Clearcus proposed the Coinage Decree, which imposed Athenian silver coinage, weights and measures on all of the allies.[23] According to one of the decree's most stringent provisions, surplus from a minting operation was to go into a special fund, and one proposing to do otherwise was subject to the death penalty.[30]

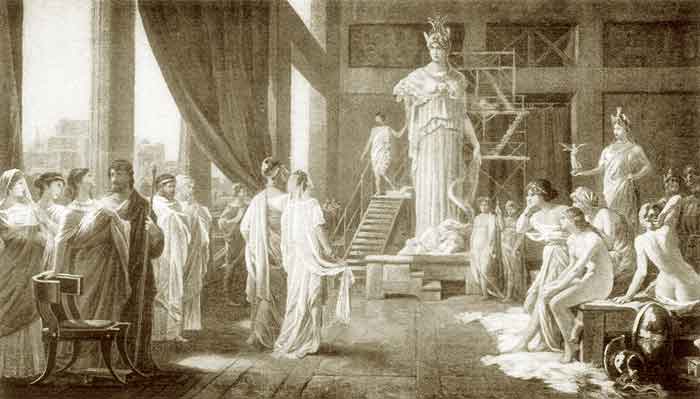

It was from the alliance's treasury that Pericles drew the necessary funds, in order to materialize his ambitious building plan centered on the "Periclean Acropolis"; a plan that included the Propylaea, the Parthenon and the golden statue of Athena, sculpted by Pericles’ friend, Phidias.[31] In 449 BC Pericles proposed a decree, allowing the use of 9.000 talents to finance the massive rebuilding program of Athenian temples.[23] Decrees like the ones mentioned reveal Athens' will to exert a more solid leadership over its allies. A. Vlachos points out that the utilization of the alliance's treasury, initiated and executed by Pericles, is one of the worst defalcations throughout human history; a defelcation that financed, however, some of the most marvellous artistic creations.[32]

The Samian War

The Samian War was the last important military event before the Peloponnesian War. After Thucydides' ostracism, Pericles was being continuously reelected to the generalship, the only office he ever officially occupied, although he constituted the absolute ruler of Athens. In 440 BC Samos was at war with Miletus and the Athenians were asked to play the role of mediator. Nonetheless, the Samians did not display the adequate level of obedience and Pericles passed a decree for his expedition to Samos, "alleging against its people that, though they were ordered to break off their war against the Milesians, they were not complying".[δ] In a naval battle the Athenians led by Pericles and the other 9 generals defeated the forces of Samos and imposed on the island an administration pleasing to them.[33] When the Samians revolted against the government which had been appointed by Athens, Pericles besieged the rebels. He compelled them to capitulate after a tough siege of 8 months, which resulted in huge discontent among the Athenian sailors.[34] Pericles also subdued Byzantium and, when he returned to Athens, he delivered the funeral oration for the soldiers who died in the expedition himself.

Pericles led Athens' fleet against Byzantium once more in 438 BC in a demonstration of the city's imperial pre-eminence,[26] but no other noteworthy military event took place until the eruption of the Peloponnesian War. Pericles focused mostly on internal projects, such as the fortification of Athens (the building of the "middle wall" about 440 BC), and on the creation of new cleruchies, such as Andros, Naxos and Thurii (444 BC) as well as Amphipolis.[35]

Personal attacks

Pericles and his friends were never immune from attack, because in ancient Athens predominance was not equivalent to absolute rule.[36] Nonetheless, just before the eruption of the war, Pericles and two of his closest associates, Phidias and the hetaira Aspasia, confronted a series of orchestrated persecutions. Phidias was first accused of embezzling gold intended for the statue of Athena and then of impiety, because, when he wrought the battle of the Amazons on the shield of Athena, he carved out a figure that suggested himself as a bald old man lifting on high a stone with both hands, and also inserted a very fine likeness of Pericles fighting with an Amazon.[37] Pericles' enemies also found a false witness against Phidias, named Menon.

Aspasia was accused of corrupting the women of Athens in order to satisfy Pericles' perversions. All these accusations were, probably, nothing more than unproven slanders, but the whole experience was very bitter for the Athenian politician. Although Aspasia was acquitted thanks to a rare emotional outburst of Pericles, his friend, Phidias, died in prison[37] and another friend of his, Anaxagoras, was attacked by the ecclesia for his religious beliefs. Further to these initial prosecutions, the ecclesia took the liberty of attacking personally Pericles by asking him to justify the ostensible profligacy and maladministration of public money.[38] According to his critics, Pericles was so afraid of the oncoming trial that he did not let the Athenians yield to the Lacedaemonians and he "kindled into flame the threatening and smoldering war, hoping thereby to dissipate the charges made against him".[38] The fact is that, when the great war erupted, Pericles did not seem as powerful as he used to be and, consequently, Athens' imperial pre-eminence started to tremble.

The Peloponnesian War

Plutarch seems to predicate that Pericles and the Athenians incited the war, scrambling to implement their hawkish tactics "with a sort of arrogance and a love of strife".[ε] Thucydides hints at the same thing, although he admires and profoundly respects his compatriot, but the great historian has, at this point, been criticised for bias and sympathy for Sparta.[στ]

The prelude of the war

Anaxagoras and Pericles by Augustin-Louis Belle (1757 – 1841).

Pericles was convinced that the war against Sparta, which could not conceal its envy of Athens' pre-eminence, was inevitable if not welcomed. Therefore, he did not hesitate to send troops to Corcyra to reinforce the Corcyraean fleet, which was fighting against Corinth.[39] In 433 BC the enemy fleets confronted each other at the Battle of Sybota and a year later the Athenians and Corinthians fought again at the Battle of Potidaea, two military events resulting in Corinth's lasting hatred of Athens. At the same period, Pericles proposed the Megarian Decree, which was something like a modern trade embargo. According to the provisions of the decree, the Megarian merchants were excluded from the market of Athens and the ports in its empire. This ban strangled the Megarian economy and strained the fragile peace between Athens and Sparta, which was allied with Megara. According to George Cawkwell, with this decree Pericles breached the Thirty Years Peace "but, perhaps, not without the semblance of an excuse".[40] The Athenians' justification was that the Megarians had cultivated the sacred land consecrated to Demeter and had given refuge to runaway slaves, a behavior deemed by the Athenians as very impious.[41]

After consultations with its allies, Sparta sent a deputation to Athens demanding some painful concessions, such as the immediate expulsion of the Alcmaeonidae family including Pericles and the retraction of the Megarian Decree. The obvious purpose of these proposals was the instigation of a confrontation between Pericles and the rabble, something that later did happen.[42] At that time, however, the Athenians followed uncomplainingly Pericles' instructions. In the first legendary oration Thucydides puts in his mouth,[43] Pericles, being certain that Sparta does not really want peace, advised the Athenians not to yield to their opponents' demands, since they were militarily stronger, especially in terms of naval force. His opinion was that endurance constituted the key for victory. The parley officially failed when the Athenians loftily turned down Sparta's demands. In exchange for retracting the Megarian Decree, they demanded from Sparta the abrogation of its internal laws against foreigners and the autonomy of its allied cities, a request implying that Sparta's hegemony was also ruthless.[44] From that moment, both alliances marshaled for war.

The first year of the war (431 BC)

In 431 BC, while peace already was on the razor's edge, Archidamus, Sparta's king, sent a new delegation to Athens, demanding the Athenians' surrender. Nevertheless, the deputation was not allowed to enter Athens, because Pericles had already passed a resolution, according to which no Spartan deputation would be welcomed, if their opponents initiated previously any hostile military actions. Since the army of Sparta was already gathered in Corinth, this manoeuvre was deemed a hostile action. Hence, Archidamus invaded Attica, but no Athenians were found there, because Pericles had previously convinced the residents to leave their farms unprotected and squeeze themselves into the city. Pericles also reassured his compatriots that, if the enemy did not plunder his farms, he would offer his property to the city. He did that being afraid that Archidamus could spare his estate, either because of their personal friendship or trying to calumniate him.[45]

|

"For heroes have the whole earth for their tomb; and in lands far from their own, where the column with its epitaph declares it, there is enshrined in every breast a record unwritten with no tablet to preserve it, except that of the heart." Pericles (Funeral Oration, Thucydides, II, 43) |

In any case, seeing the pillage, the Athenians were outraged and they started in some indirect ways to express their discontent towards their leader. In the eyes of many Athenians, Pericles drew them to war. Nonetheless, Pericles did not give in to the pressures for immediate action against the enemy and he did not revise his initial strategy. He also avoided convening the ecclesia, in an attempt to ease the tensions. At the same time, he sent a fleet of 100 ships to loot the coasts of the Peloponnese[46] and charged the cavalry to guard the ravaged farms close to the walls of the city. When the enemy retired and the pillage came to an end, Pericles proposed a decree, according to which the authorities of the city should put aside 1.000 talents and 100 ships, in case Athens was attacked by naval forces. According to the most stringent provision of the decree, even the simple proposition for a different utilization of the money or ships would entail the penalty of death.

During the autumn of 431 BC, Pericles led the Athenian forces that invaded Megara and a few months later (winter of 431 BC-430 BC) he delivered his monumental and emotional Funeral Oration,[47] honoring the Athenians who died for their city.

Last military operations and death

In 430 BC, the army of Sparta looted Attica for a second time, but Pericles was not daunted and refused to revise his initial strategy. Unwilling to engage the Spartan army in battle, he preferred to lead himself a naval force of 100 ships, which plundered once again the coasts of Peloponnese. According to Plutarch, just before the sailing of the ships an eclipse of the moon frightened the crews, but Pericles used his astronomical knowledge, taught to him by Anaxagoras, to calm them down.[48] In the summer of the same year the epidemic broke out and decimated the Athenians.[49] About the nature of the disease nobody can be sure, but, taking into consideration its symptoms, most researchers and scientists now believe that it was typhus or typhoid fever and not cholera, plague or measles.[ζ] In any case, the city's plight, caused by the epidemic, triggered a new wave of public uproar and Pericles took great pains to defend himself in his last emotional speech exposed by Thucydides.[50] This is considered to be a monumental oration, revealing Pericles' virtues but also his bitterness towards his compatriots' ingratitude. Temporarily, he managed to tame the rabble's resentment and to ride out the storm, but his internal enemies' final bid to undermine him came off; they achieved to deprive him of the generalship and to fine him with an amount of money estimated between 15 and 50 talents.[51] Ancient sources mention Cleon, a rising and dynamic protagonist of the Athenian political scene during the war, as the public prosecutor in Pericles' trial.[51]

Nevertheless, within just a year, in 429 BC, the Athenians not only forgave him but they also reelected him as strategos (general).[η] He was reinstated in command of the Athenian army and led all its military operations during 429 BC,[26] having once again under his control the levers of power. However, the death of both his legitimate sons from his first wife, Xanthippus and his beloved Paralus, hit by the epidemic, was a huge blow for Pericles. With his morale undermined, he burst into tears and not even Aspasia's companionship could console him. He legitimised his third son, Pericles the younger (Athenians allowed a change in the law that made Pericles' half-Athenian son a citizen and legitimate heir[52]), whose mother was Aspasia. He died in the autumn of 429 BC after being affected by the disease.

Just before his death, Pericles' friends were concentrated around his bed, enumerating his virtues during peace and underscoring his nine war trophies. Pericles, though moribund, heard them and interrupted them, pointing out that they forgot to mention his fairest and greatest title to their admiration; "for", said he, "no living Athenian ever put on mourning because of me".[53] Pericles lived during the first two and a half years of the Peloponnesian War and, according to Thucydides, his death constituted a disaster for Athens, since his successors were inferior to him;[54] they preferred to incite all the bad habits of the rabble and they followed an unstable policy, endeavoring to be likeable rather than useful. With these bitter comments, Thucydides not only laments the loss a man he admired, but he also heralds the flickering of Athens' unique glory and grandeur.

Personal life

Pericles, following Athenian custom, was first married to one of his closest relatives and he had with his wife two sons, Xanthippus and Paralus. Nevertheless, his marriage was not a happy one. As a result, Pericles got divorced (c. 445 BC) and offered his wife to another husband with the agreement of her male relatives.[55] Unfortunately, we do not know the name of his first wife; the only information about her is that she was the wife of Hipponicus, before being married to Pericles, and the mother of Callius from this first marriage.[56]

|

"For men can endure to hear others praised only so long as they can severally persuade themselves of their own ability to equal the actions recounted: when this point is passed, envy comes in and with it incredulity." Pericles (Funeral Oration, Thucydides, II, 35) |

The woman he really adored was Aspasia, a hetaera, whose intellectual powers astonished Pericles. She became his mistress and they began to live together as if they were married. This relationship aroused many reactions and even Pericles' own son, Xanthippus, who had political ambitions, did not hesitate to slander his father.[57] Nonetheless, these persecutions did not undermine Pericles' morale, although he had to burst into tears in order to protect his beloved Aspasia, when she was accused of corrupting Athenian society. His greatest personal tragedy was the death of his sister and of both his legitimate sons, Xanthippus and Paralus, all affected by the epidemic, a calamity he never managed to overcome.

Assessments

Pericles marked a whole era and inspired conflicting judgments about his various and significant decisions, which is something normal for a political personality of his magnitude. The fact that he constituted at the same time a vigorous statesman, general and orator makes more difficult and complex the objective and comprehensive assessment of his actions.

Political leadership

While contemporary scholars, such as Sarah Ruden,[58] label Pericles as a populist, a demagogue and a hawk, most of them laud his inspired and charismatic leadership. It is true that during his youth, when he first confronted Cimon, he introduced policies, certain aspects of which could be deemed demagogic. Nonetheless, a few years later, he adopted moderation and recalled Cimon for the sake of Athens, a characteristic exhibition of public spirit. According to Plutarch, after assuming the leadership of Athens, "he was no longer the same man as before, nor alike submissive to the people and ready to yield and give in to the desires of the multitude as a steersman to the breezes".[59] It is told that, when his political opponent, Thucydides, was asked by Sparta's king, Archidamus, if he or Pericles was a better fighter, Thucydides answered without any hesitation that Pericles was a better fighter, because, even when he is defeated, he achieves to convince the audience that he won.[26] In matters of character, Pericles was above reproach in the eyes of the ancient historians, since "he kept himself untainted by corruption, although he was not altogether indifferent to money-making".[8]

Thucydides, an admirer of Pericles, maintains that Athens was "in name a democracy but, in fact, governed by its first citizen".[54] Through this laconic comment, the historian illustrates what he perceives as Pericles' charisma to lead, convince and, sometimes, manipulate. Although Thucydides mentions Pericles' fining,[54] he avoids to expose the accusations against the politician[θ] and underlines Pericles' integrity. On the other hand, in one of his dialogues, Plato rejects the glorification of Pericles[60] and puts in Socrates' mouth the following comments: "As far as I know, Pericles made the Athenians slothfull, garrulous and avaricious, by starting the system of public fees".[61] These contradicting comments make it even more difficult to figure out if Pericles was the hawkish politician who paved the way for the populism of his incompetent successors or the summa virtus of a statesman, an insurmountable pattern, as Thucydides wants to present him.

In any case, the most flattering comment of Thucydides is that Pericles "was not carried away by the people, but he was the one guiding the people",[54] namely he was not manipulated by the mob, but he was the one manipulating the mob, an ability his successors seem to have lacked.[ι]

Military achievements

From about 454 BC until his death, namely for more than 20 years, Pericles led numerous expeditions, mainly naval ones. Being always cautious, he never undertook of his own accord a battle involving much uncertainty and peril and he did not accede to the "vain impulses of the citizens".[62] He based his military policy on Themistocles' principle that Athens' predominance depends on its superior naval firepower. That is why the strengthening of the navy was one of his main preoccupations. Nonetheless, his strategic genius remains questioned and a common criticism against him is that he always was a better politician and orator than strategist.

|

"These glories may incur the censure of the slow and unambitious; but in the breast of energy they will awake emulation, and in those who must remain without them an envious regret. Hatred and unpopularity at the moment have fallen to the lot of all who have aspired to rule others." Pericles (Third Oration, Thucydides, II, 64) |

His tactics during the Peloponnesian War were also criticized. Many of his internal opponents advocated a more aggressive stance against Sparta and the pillage of Attica reinforced the voices of opposition. In an attempt to find out if the more or less passive strategy he sculpted was right and if the Athenians lost the war because of his initial choices, we must point out that Pericles' syllogism was likely more political than military in nature. He probably believed that in a prolonged war the winner would be the one who would endure more and a prosperous city like Athens met all the requirements for achieving a triumph, if its leadership could remain resolute, patient and focused on its strategic goals. And, had he lived longer, he may have attained his goals through his persistence. The problem may be that those succeeding him lacked his genius, his composure, and a clear vision. The most charismatic of his successors, Alcibiades, would have a completely different plan in mind and what may be called a dubious agenda.

Skill of oratory

Thucydides' contemporary commentators are still trying to unriddle the puzzle of Pericles' orations and to figure out if the skillful wording belongs to the Athenian statesman or if it is merely a creation of the historian.[ια] Unfortunately, it seems that this is a question nobody will ever answer with certainty,[ιβ] taking into consideration the fact that Pericles never wrote down or distributed his orations;[ιγ] Thucydides recreated three of them[63] from memory and, thereby, it cannot be ascertained that he did not add his own notions and thoughts. In any case, Pericles was a main source of his inspiration, and the orations attributed to him are one of the main reasons for studying Thucydides' influential work, especially the Funeral Oration and his emotional third oration.[50] One could not fail to note, however, that the passionate and idealistic literary style of the speeches Thucydides attributes to Pericles is completely at odds with Thucydides' own cold and analytical writing style,[ιδ] although this might be the result of the incorporation of the genre of rhetoric into the genre of historiography. That is to say, Thucydides could simply have used two different writing styles for two different purposes.

Pericles adopted "an elevated mode of speech, free from the vulgar and knavish tricks of mob-orators"[64] and, according to Diodorus Siculus, he "excelled all his fellow citizens in skill of oratory".[65] He avoided any gimmicks while orating, contrary to the passionate Demosthenes, and imposed himself with his tranquil manner of speaking,[66] with the plethora of his grandiose ideas, with his elegance and inspiration. The fact that he was quick-witted is demonstrated by the way he confronted his political opponent, Thucydides, and achieved the immediate swing of the mob in his favor. The ancient Greek writers call him "Olympian" and they vaunt him, underlining that "he was thundering and lightening and exciting Greece"[67] and he was carrying the weapons of Zeus when orating. According to Quintilian,[68] Pericles would always prepare assiduously for his orations and, before going on the rostrum, he would always pray to the Gods, so as not to utter any improper word.[69] Sir Richard C. Jebb concludes that "unique as an Athenian statesman, Pericles must have been in two respects unique also as an Athenian orator; first, because he occupied such a position of personal ascendancy as no man before or after him attained; secondly, because his thoughts and his moral force won him such renown for eloquence as no one else ever got from Athenians".[70]

Legacy

According to K. Paparrigopoulos, Pericles was "the ideal type of the perfect statesman in ancient Greece".[71] Comparing the virtues of the most prominent Athenian statesmen, the Greek historian concludes that "Cimon was surely a better general; Themistocles might have been a better politician and Demosthenes a better orator, but Pericles was, at the same time a great general, statesman and orator".[71]

He bequeathed a very influential legacy to the next generations; the monuments of the Acropolis and the culmination of classical literature are related to his name. According to K. Paparrigopoulos, "he decorated his city with masterpieces, which were sufficient to render the name of Greece immortal in our world".[71] Nowadays, humanity can still admire his living heritage, the achievements of Athenian civilization in the Golden Age of Pericles.

Notes

α. ^ Estimations about Pericles' date of birth are contradictory. C.W. Fornara and L.J. Samons II maintain that the lower terminus of his date of birth is 492/1 BC, although he may have been born by c. 500 BC or earlier.[12]

β. ^ According to Plutarch, Agariste was Cleisthenes' granddaughter,[4] but she was his niece, rather.

γ. ^ According to Aristotle, Aristodicus of Tanagra killed Ephialtes,[72] though Idomeneus accuses Pericles of the murder. However, Plutarch does not put trust in him.[21]

δ. ^ According to Plutarch, it was thought that Pericles proceeded against the Samians to gratify Aspasia of Miletus.[73]

ε. ^ Plutarch exposes these allegations without espousing them.[37] Thucydides insists, however, that the Athenian politician was still powerful.[74] A.W. Gomme[75] and A. Vlachos[76] support Thucydides' view.

στ. ^ A. Vlachos, in an excellent survey of his, maintains that Thucydides' narration gives the impression that Athens' alliance had become an authoritarian and oppressive empire, while the historian makes no comment for Sparta's equally harsh rule. A. Vlachos underlines, however, that Athens' crushing could entail a much more ruthless Spartan empire, something that indeed happened. Hence, the historian's hinted assertion that the Greek public opinion espoused Sparta's pledges of liberating Greece almost uncomplainingly seems naive and tendentious.[77] Ste Croix, for his part, argues that Athens' imperium was neither authoritarian nor unpopular but welcomed and valuable for the stability of democracy all over Greece.[78] According to Fornara-Samons, "any view proposing that popularity or its opposite can be inferred simply from narrow ideological considerations is superficial".[79]

ζ. ^ According to A.W.Gomme[80]and A. Vlachos.[81] For this issue see also Plague of Athens, typhus and typhoid fever.

η. ^ Pericles held the generalship from 444 BC till 430 BC without interruption.[36]

θ. ^ A. Vlachos criticizes the historian for this omission and maintains that Thucydides' admiration for the Athenian statesman makes him ignore not only the well-grounded accusations against him but also the mere gossips, namely the allegation that Pericles had corrupted the volatile rabble, so that to assert himself.[82]

ι. ^ Plutarch underlines, however, that "many others say that the people was first led on by him into allotments of public lands, festival-grants, and distributions of fees for public services, thereby falling into bad habits, and becoming luxurious and wanton under the influence of his public measures, instead of frugal and self-sufficing".[13]

ια. ^ According to A.Vlachos, Thucydides must have been about 30 years old, when Pericles delivered his Funeral Oration and he was probably among the audience.[83]

ιβ. ^ A. Vlachos accurately points out that "I do not want to wonder who wrote this marvellous oration; I just know that these were the words, which should have been told at the end of 431 BC".[83] According to Sir Richard C. Jebb, "the Thucydidean speeches of Pericles in Thucydides doubtless give the general ideas of Pericles with essential fidelity; it is possible, further, that they may contain recorded sayings of his like those in Aristotle: but it is certain that they cannot be taken as giving the form of the statesman's oratory".[70] J.F. Dobson believes that "though the language is that of the historian, some of the thoughts may be those of the statesman".[84] I.Th. Kakridis predicates that "the Funeral Oration is actually an almost exclusive creation of Thucydides", since "the real audience does not consist of the Athenians of the beginning of the war, but of the generation of 400 BC, which suffers under the repercussions of the defeat".[85]

ιγ. ^ That is what Plutarch predicates.[69] Nonetheless, according to Suda,[86] Pericles constituted the first orator who systematically wrote down his orations. Cicero speaks about Pericles' writings,[87] but his remarks do not seem credible. Most probably, other writers used his name.[88]

ιδ. ^ I. Kalitsounakis believes that these three speeches definitely include the main traits of Pericles' policies. He also points out that "no reader can overlook the sumptuous rythme of the Funeral Oration as a whole and the singular correlation between the impetuous emotion and the marvellous style, attributes of speech that Thucydides ascribes to no other orator but Pericles".[26]

Citations

|

Time line

Timeline of Pericles' life (c.495 BC-429 BC)

|

References

|

Primary sources (Greeks and Romans)

|

Secondary sources

|

Further reading

- Evelyn Abbott (1898). Pericles and the Golden Age of Athens. G. P. Putnam's Sons.

- Roger Brock, Stephen Hodkinson (2003). Alternatives to Athens: Varieties of Political Organization and Community in Ancient Greece. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0199258104.

- Percy Gardner (1902). Ancient Athens.

- A. J. (Arthur James) Grant (1893). Greece in the Age of Pericles. John Murray.

- Jon Hesk (2000). Deception and Democracy in Classical Athens. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521643228.

- Donald Kagan (1991). Pericles of Athens and the Birth of Democracy. The Free Press. ISBN 0684863952.

- C. Douglas Lummis (1997). Radical Democracy. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801484510.

- Josiah Ober (2001). Political Dissent in Democratic Athens: Intellectual Critics of Popular Rule. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691089817.

- P J Rhodes (2005). A History of the Classical Greek World: 478-323 BC. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 063122565X.

- Leonard Whibley (1889). A History of the Classical Greek World: 478-323 BC. University Press.

Links

|

Biographies

Pericles and the Athenian democracy

|

Further assessments about Pericles and his era

|

When the orators, who sided with Thucydides and his party, were at one time crying out, as their custom was, against Pericles, as one who squandered away the public money, and made havoc of the state revenues, he rose in the open assembly and put the question to the people, whether they thought that he had laid out much; and they saying, "Too much, a great deal," Then," said he, "since it is so, let the cost not go to your account, but to mine; and let the inscription upon the buildings stand in my name." When they heard him say thus, whether it were out of a surprise to see the greatness of his spirit or out of emulation of the glory of the works, they cried aloud, bidding him to spend on, and lay out what he thought fit from the public purse, and to spare no cost, till all were finished. Plutarch, Pericles

|

Plutarch's Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans Alcibiades and Coriolanus - Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar - Aratus & Artaxerxes and Galba & Otho |

|

Athenian statesmen | Ancient Greece Aeschines - Agyrrhius - Alcibiades - Andocides - Archinus - Aristides - Aristogeiton - Aristophon - Autocles Callistratus - Chremonides - Cleisthenes - Cleon - Critias - Demades - Demetrius Phalereus - Demochares - Democles - Demosthenes Ephialtes - Eubulus - Hyperbolos - Hypereides - Kimon - Kleophon - Lycurgus Miltiades - Moerocles - Nicias - Peisistratus - Pericles - Philinus - Phocion - Themistocles |

Pericles Of Athens And The Birth Of Democracy- , Donald Kagan

Pericles of Athens- , Vincent Azoulay

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/"

All text is available under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License

| Ancient Greece

Science, Technology , Medicine , Warfare, , Biographies , Life , Cities/Places/Maps , Arts , Literature , Philosophy ,Olympics, Mythology , History , Images Medieval Greece / Byzantine Empire Science, Technology, Arts, , Warfare , Literature, Biographies, Icons, History Modern Greece Cities, Islands, Regions, Fauna/Flora ,Biographies , History , Warfare, Science/Technology, Literature, Music , Arts , Film/Actors , Sport , Fashion --- |