.

In the purest landscape, the human subject is the immortality of the soul by the faithfulness of love: in both the Turner landscapes it is the death of the body by the impatience and error of love. The one is the first glimpse of Hesperia to Æsacus:[*]

"Aspicit Hesperien patria Cebrenida ripa,

Injectos humeris siccantem sole capillos:"

in a few moments to lose her forever. The other is a mythological subject of deeper meaning, the death of Procris.

94. I just now referred to the landscape by John Bellini in the National Gallery as one of the six best existing of the purist school, being wholly felicitous and enjoyable. In the foreground of it indeed is the martyrdom of Peter Martyr; but John Bellini looks upon that as an entirely cheerful and pleasing incident; it does not disturb or even surprise him, much less displease in the slightest degree.

Now, the next best landscape[**] to this, in the National Gallery, is a Florentine one on the edge of transition to the Greek feeling; and in that the distance is still beautiful, but misty, not clear; the flowers are still beautiful, but—intentionally—of the color of blood; and in the foreground lies the dead body of Procris, which disturbs the poor painter greatly; and he has expressed his disturbed mind about it in the figure of a poor little brown—nearly black—Faun, or perhaps the god Faunus himself, who is much puzzled by the death of Procris, and stoops over her, thinking it a woeful thing to find her pretty body lying there breathless, and all spotted with blood on the breast.

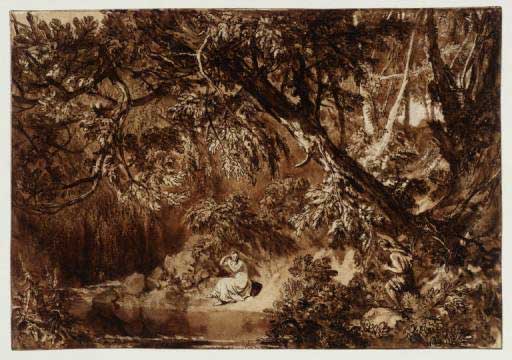

95. You remember I told you how the earthly power that is necessary in art was shown by the flight of Dædalus to the 'ερπετον Minos. Look for yourselves at the story of Procris as related to Minos in the fifteenth chapter of the third book of Apollodorus; and you will see why it is a Faun who is put to wonder at her, she having escaped by artifice from the Bestial power of Minos. Yet she is wholly an earth-nymph, and the son of Aurora must not only leave her, but himself slay her; the myth of Semele desiring to see Zeus, and of Apollo and Coronis, and this having all the same main interest. Once understand that, and you will see why Turner has put her death under this deep shade of trees, the sun withdrawing his last ray; and why he has put beside her the low type of an animal's pain, a dog licking its wounded paw.

96. But now, I want you to understand Turner's depth of sympathy farther still. In both these high mythical subjects the surrounding nature, though suffering, is still dignified and beautiful. Every line in which the master traces it, even where seemingly negligent, is lovely, and set down with a meditative calmness which makes these two etchings capable of being placed beside the most tranquil work of Holbein or Dürer. In this "Cephalus" especially, note the extreme equality and serenity of every outline. But now here is a subject of which you will wonder at first why Turner drew it at all. It has no beauty whatsoever, no specialty of picturesqueness; and all its lines are cramped and poor.

The crampness and the poverty are all intended. This is no longer to make us think of the death of happy souls, but of the labor of unhappy ones; at least, of the more or less limited, dullest, and—I must not say homely, but—unhomely life of the neglected agricultural poor.

It is a gleaner bringing down her one sheaf of corn to an old watermill, itself mossy and rent, scarcely able to get its stones to turn. An ill-bred dog stands, joyless, by the unfenced stream; two country boys lean, joyless, against a wall that is half broken down; and all about the steps down which the girl is bringing her sheaf, the bank of earth, flowerless and rugged, testifies only of its malignity; and in the black and sternly rugged etching—no longer graceful, but hard, and broken in every touch—the master insists upon the ancient curse of the earth—"Thorns also and Thistles shall it bring forth to thee."

97. And now you will see at once with what feeling Turner completes, in a more tender mood, this lovely subject of his Yorkshire stream, by giving it the conditions of pastoral and agricultural life; the cattle by the pool, the milkmaid crossing the bridge with her pail on her head, the mill with the old millstones, and its gleaming weir as his chief light led across behind the wild trees.

*) Ovid, "Metamorphoses," XI. 769

**) (Of the Purist school.)

See also : Greek Mythology. Paintings, Drawings

| Ancient Greece

Science, Technology , Medicine , Warfare, , Biographies , Life , Cities/Places/Maps , Arts , Literature , Philosophy ,Olympics, Mythology , History , Images Medieval Greece / Byzantine Empire Science, Technology, Arts, , Warfare , Literature, Biographies, Icons, History Modern Greece Cities, Islands, Regions, Fauna/Flora ,Biographies , History , Warfare, Science/Technology, Literature, Music , Arts , Film/Actors , Sport , Fashion --- |

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org"

All text is available under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License