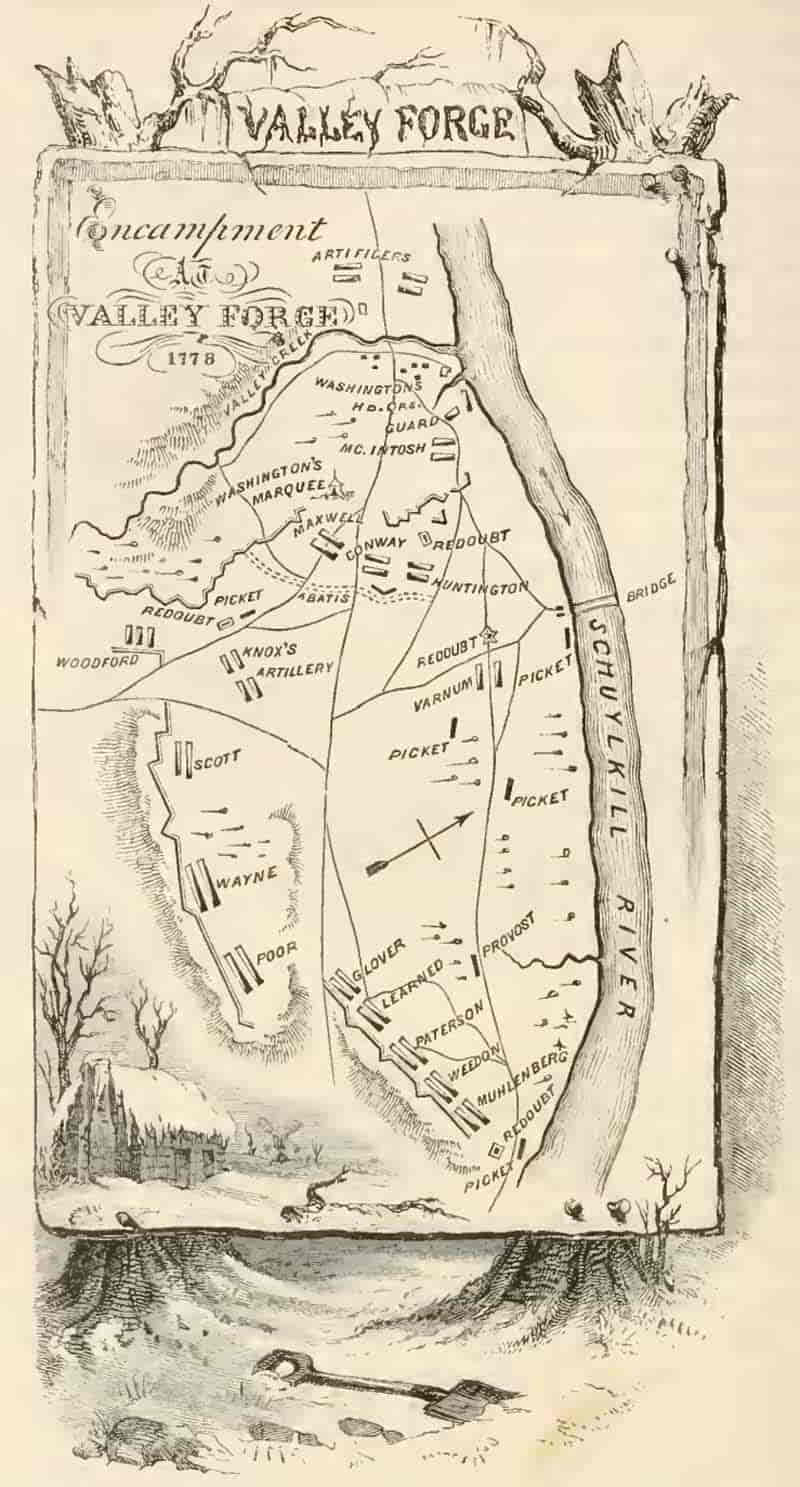

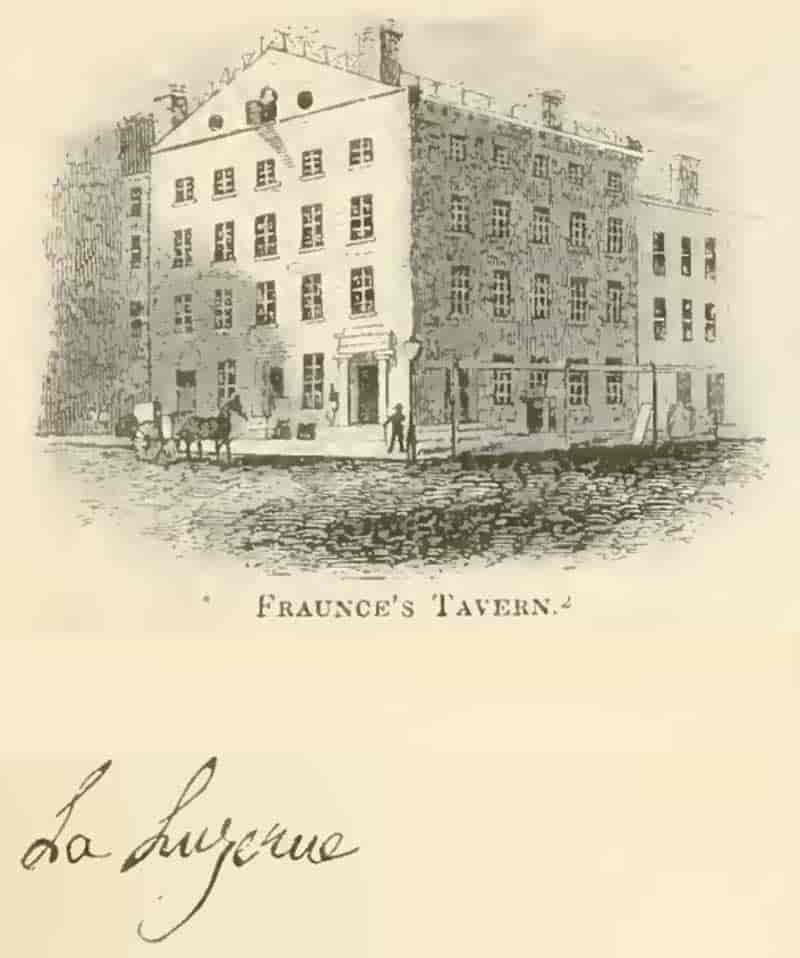

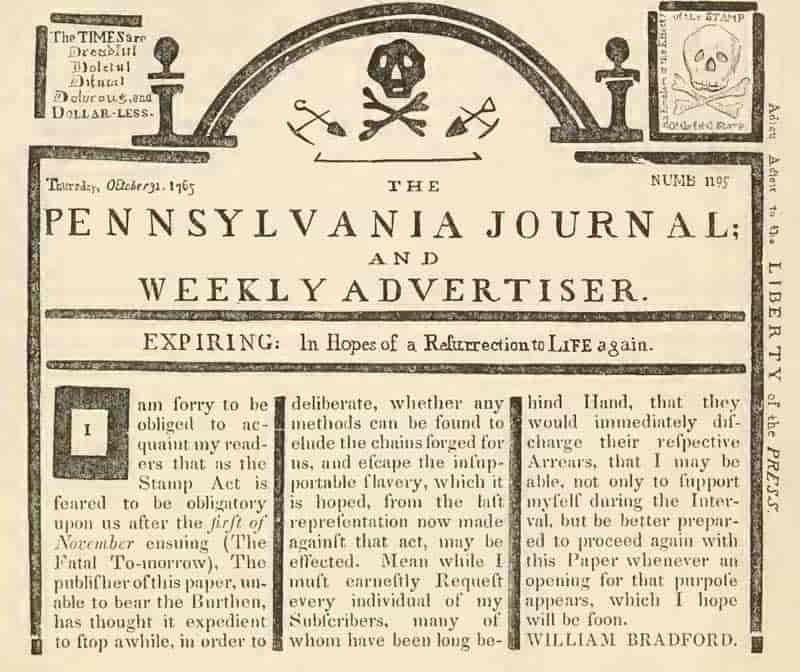

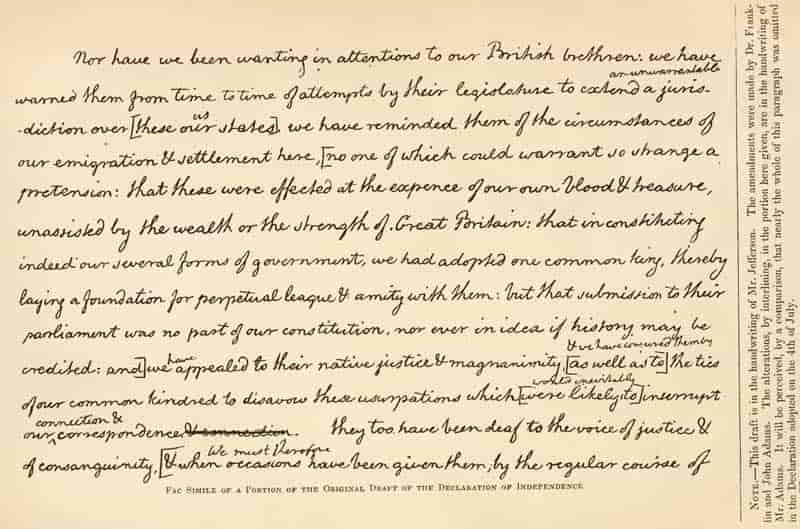

.

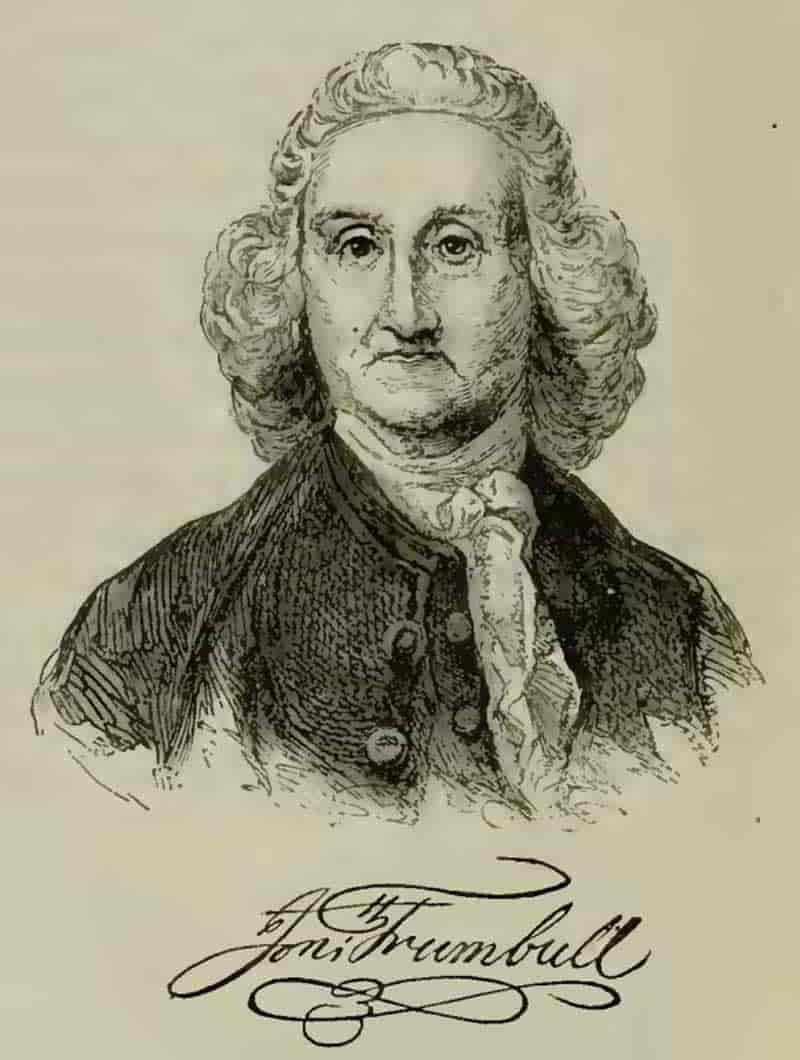

THE PICTORIAL FIELD-BOOK OF THE REVOLUTION

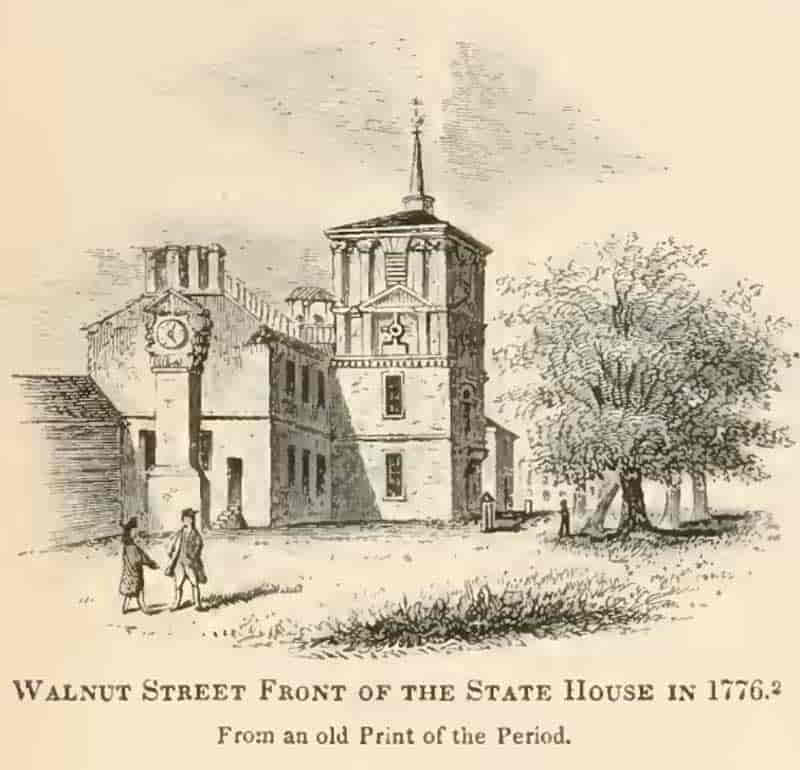

Illustrations, By Pen And Pencil, Of The History, Biography, Scenery, Relics, And Traditions Of The War For Independence.

By Benson J, Lossing,

With Several Hundred Engravings On Wood, By Lossing And Barritt, Chiefly From Original Sketches By The Author.

Volume II (of II Volumes)

Harper & Brothers, Publishers,

1 8 5 2.

TRANSCRIBER'S NOTE:

Among the several challenging issues with this two volume set were:

1. The duplication of the last eight chapters of Volume I. inserted at the beginning of Volume II.; and there given chapter numbers starting with Chapter I".

2. That the index in Volume I did not include any references to the last eight chapters. The index references to these duplicated chapters were however include in Volume II.

3. Spelling of many words and names in both volumes was inventive and variable from one paragraph to another. In proofing this file I began to believe the printer was short of "e's c's and o's" and began to substitute one for the others. I am sure I missed many of these.

4. The grammar used was often unacceptable today.

5. Nearly every page had long footnotes in extremely small print. Some of the footnotes referred to other footnotes. Many of the longer footnotes and footnotes to footnotes were placed at the bottom of succeeding pages, making the organization of these to the bottom of the page referring to them was challenging.

6. The extremely small and blurred print was often beyond the ability of the best Optical Character Recognition program available.

| Volume I. |

CONTENTS

009

CHAPTER I.

"When Freedom, from her mountain height,

Unfurl'd her standard to the air,

She tore the azure robe of night,

And set the stars of glory there.

She mingled with its gorgeous dyes

The milky baldrie of the skies,

And striped its pure celestial white

With streakings of the morning light;

Then from his mansion in the sun

She call'd her eagle-bearer down,

And gave into his mighty hand

The symbol of her choseth land."

Joseph Rodman Drake.

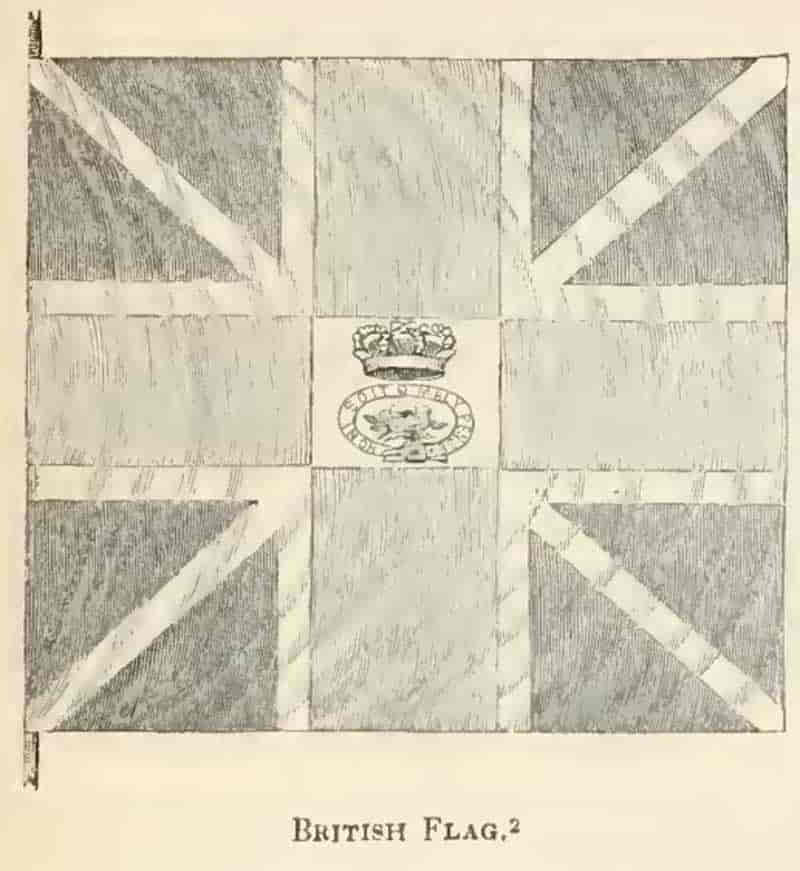

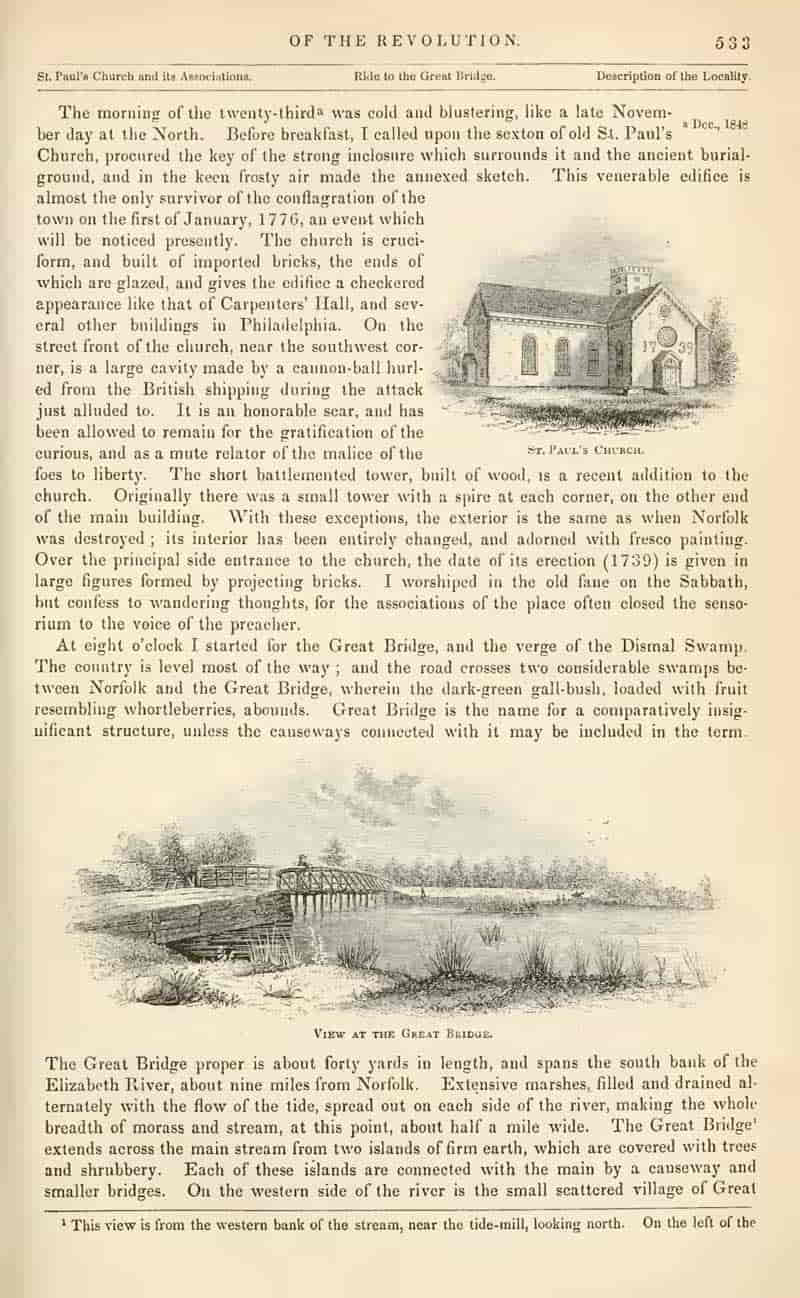

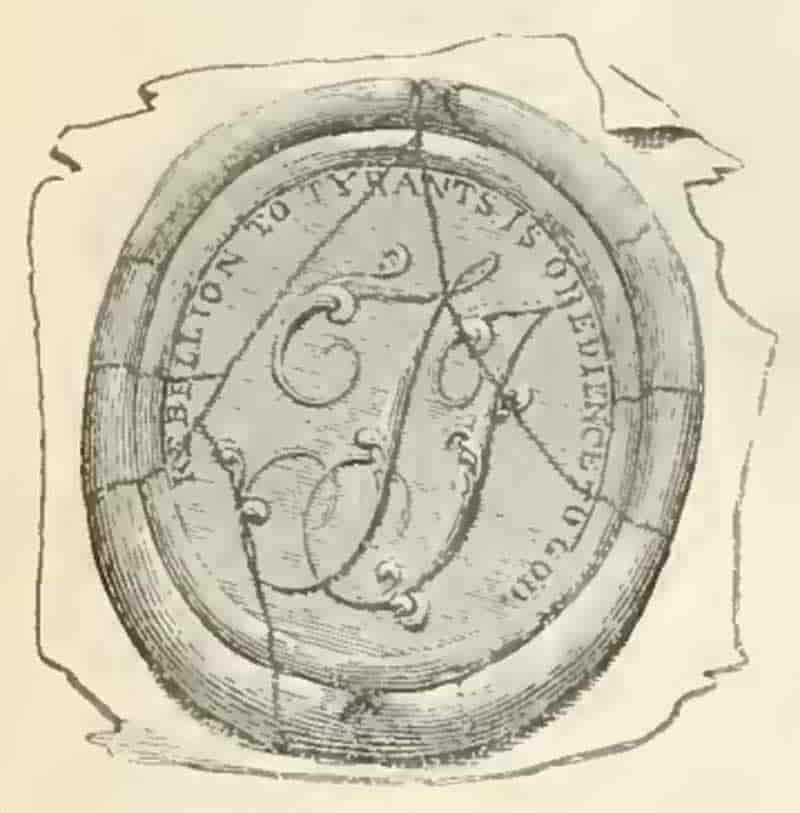

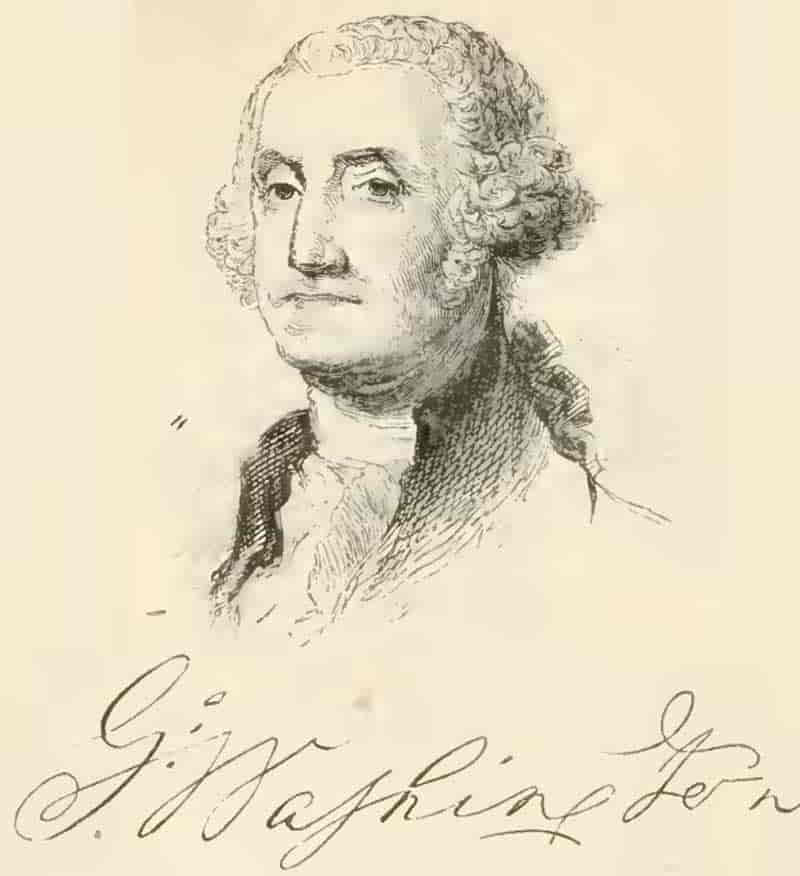

N the first of January, 1776, the new Continental army was organized, and on that day the Union FLAG OF THIRTEEN STRIPES was unfurled, for the first time, in the American camp at Cambridge. On that day the king's speech (of which I shall presently write) was received in Boston, and copies of it were sent, by a flag, to Washington. The hoisting of the Union ensign was hailed by Howe as a token of joy on the receipt of the gracious speech, and of submission to the crown. *. This was a great mistake, for at no time had Washington been more determined to attack the king's troops, and to teach oppressors the solemn lesson that "Resistance to tyranny is obedience to God."

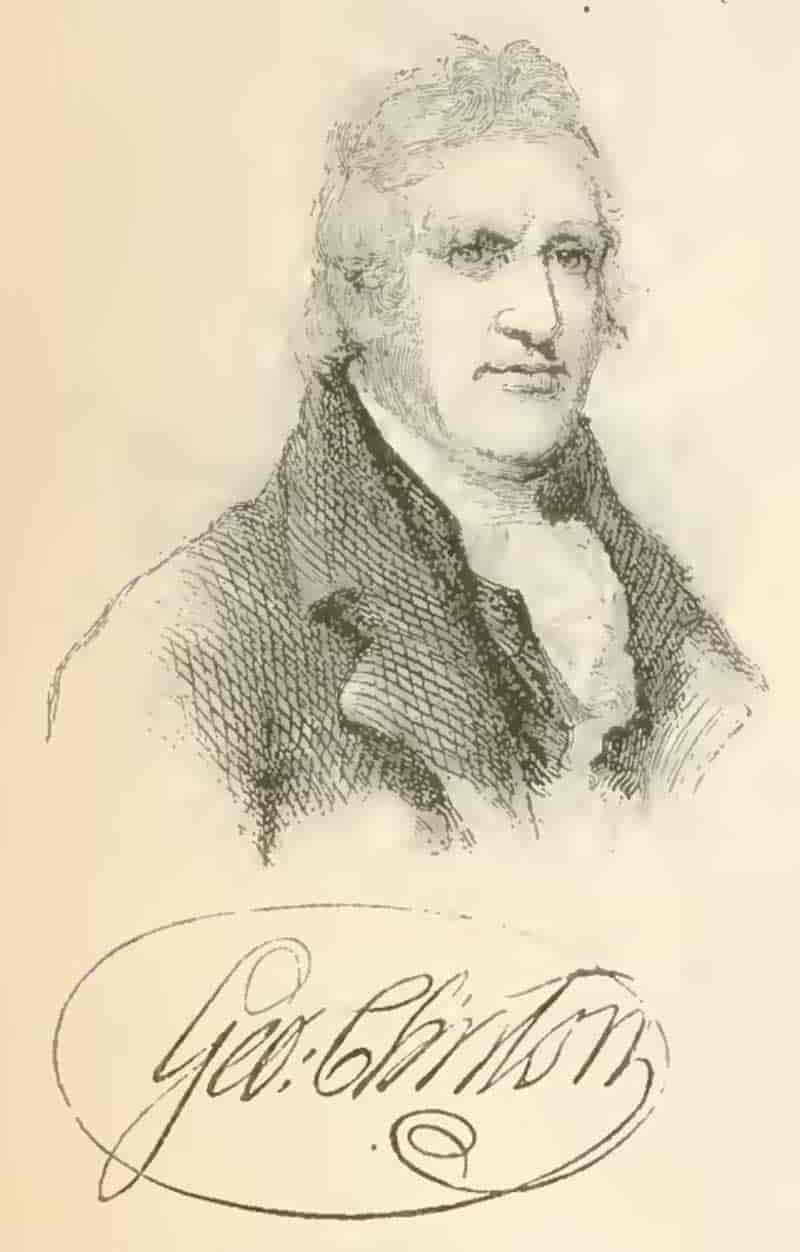

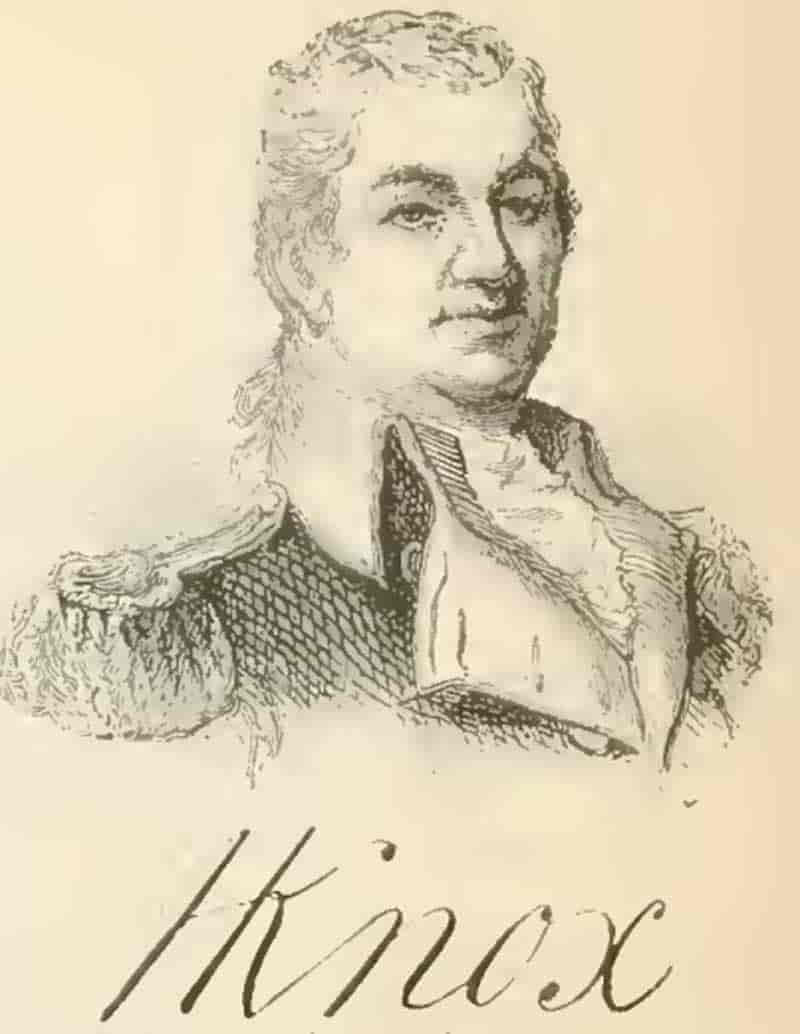

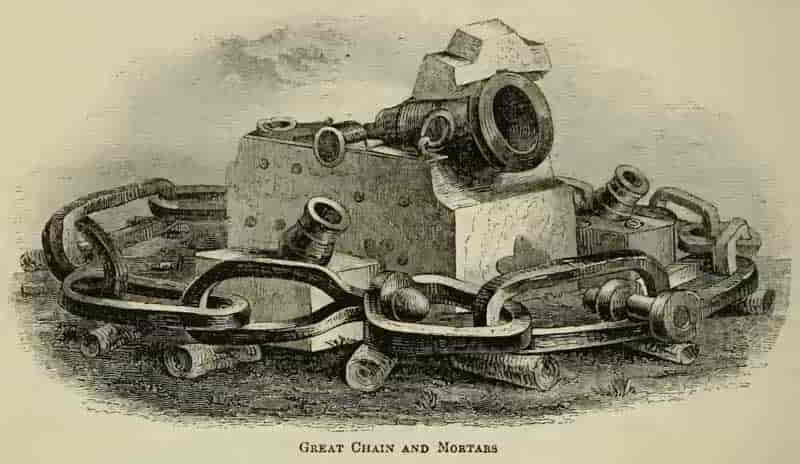

After the arrival of Colonel Knox with military stores from the north, whither he had been sent in November, the commander-in-chief resolved to attack the enemy, either by a general assault, or by bombardment and cannonade, notwithstanding the British force was then nearly equal to his in numbers, and greatly superior in experience. Knox brought with him from Fort George, on forty-two sleds, eight brass mortars, six iron mortars, two iron howitzers, thirteen brass cannons, twenty-six iron cannons, two thousand three hundred pounds of lead, and one

* Washington, in a letter to Joseph Reed, written on the 4th of January, 1776, said, "The speech I send you. A volume of them was sent out by the Boston gentry, and, farcical enough, we gave great joy to them without knowing or intending it; for on that day, the day which gave being to the new army, but before the proclamation came to hand, we had hoisted the Union flag, in compliment to the United Colonies. But behold! it was received in Boston as a token of the deep impression the speech had made upon us, and as a signal of submission. So we hear by a person out of Boston last night. By this time, I presume, they begin to think it strange that we have not made a formal surrender of our lines." The principal flag hitherto used by the army was plain crimson. Referring to the reception of the king's speech, the Annual Register (1776) says, "So great was the rage and indignation [of the Americans], that they burned the speech, changed their colors from a plain red ground which they had hitherto used, to a flag with thirteen stripes, as a symbol of the number and union of the colonies." The blue field in one corner, with thirteen stars, was soon afterward adopted; and by a resolution of the Continental Congress, already referred to, passed on the 14th of June, 1777,* this was made the national flag of the United States.

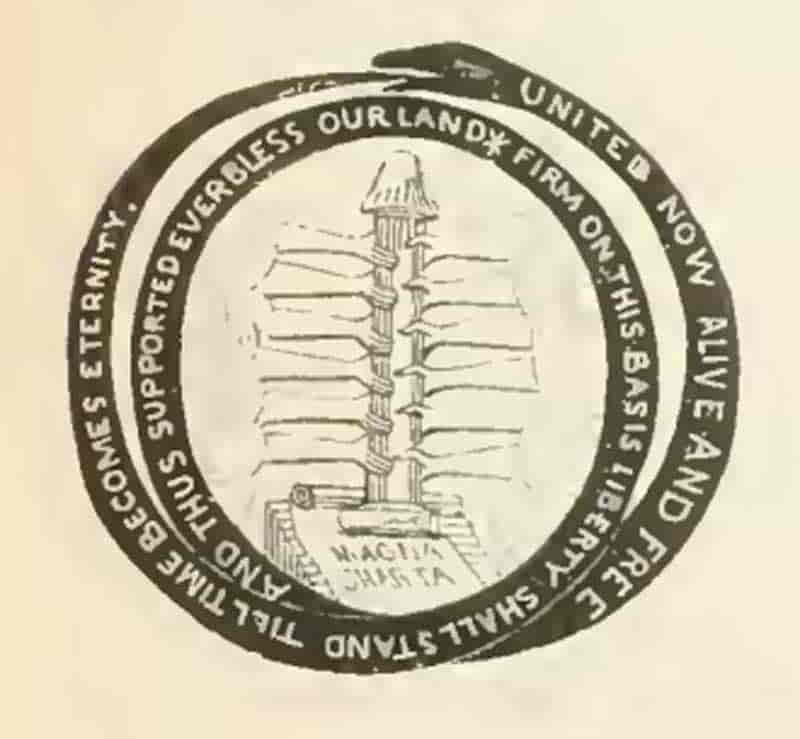

*This flag bore the device of the English Union, which distinguishes the Royal standard of Great Britain. It is composed of the cross of St. George, to denote England, and St. Andrew's cross, in the form of an X, to denote Scotland. This device was placed in the corner of the Royal Flag, after the accession of James the Sixth of Scotland to the throne of England as James the First. A picture of this device may be seen on page 321, Vol. It. It must be remembered that at thia time the American Congress had not declared the colonies "free and independent" states, and that even yet the Americans proffered their warmest loyalty to British justice, when it should redress their grievances. The British ensign was therefore not yet discarded, but it was used upon their flags, as in this instance, with the field composed of thirteen stripes, alternate red and white, as emblematic of the union of the thirteen colonics in the struggle for freedom. Ten months before, "a Union flag with a red field" was hoisted at New York, upon the Liberty-pole on the "Common," bearing the inscription—"George Rex, and the Liberties of America," and upon the other side, "No Popery." It was this British Union, on the American flag, which caused the misapprehension of the British in Boston, alluded to by Washington. It was a year and a half later (and a year after the colonies were declared to be Independent states), that, by official orders, "thirteen white stars upon a blue field" was a device substituted for the British Union, and then the "stripes and stars" became our national banner.

Plan of Attack on Boston.—Re-enforcement of the Army.—Council of War.—Number of the Troops.—Situation of Washington.

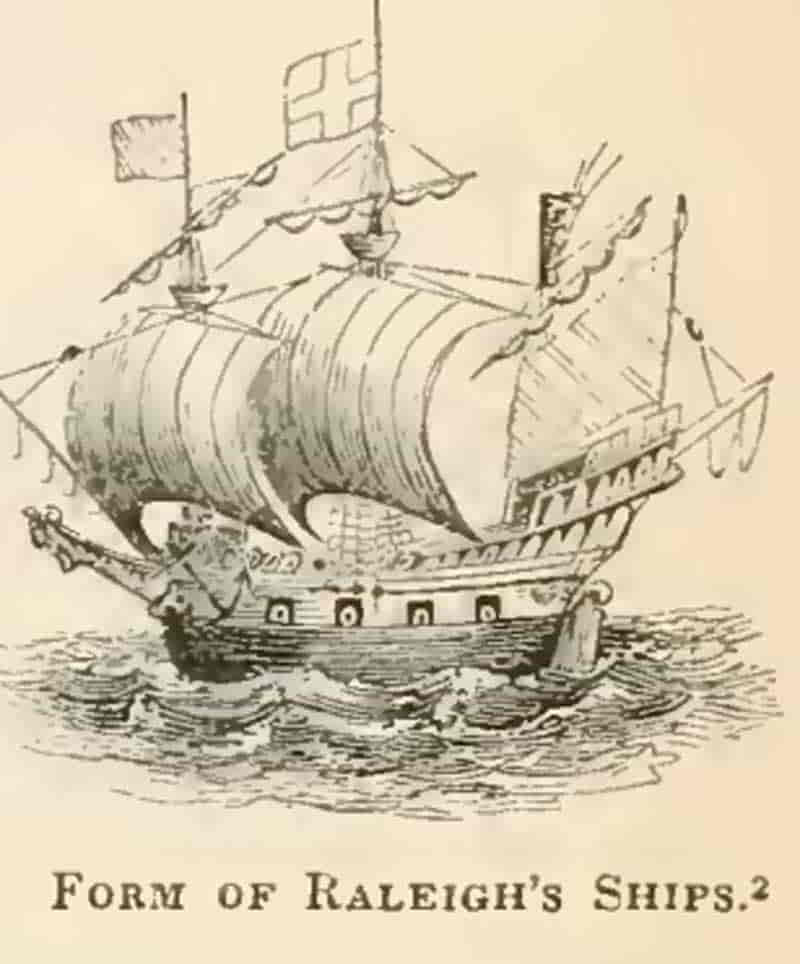

010barrel of flints. In the harbor of Boston the enemy had several vessels of war, * and upon Bunker Hill his works were very strong.

Washington's plan depended, in its execution, upon the weather, as it was intended to pass the troops over to Boston, from Cambridge, on the ice, if it became strong enough. The Neck was too narrow and too well fortified to allow him to hope for a successful effort to enter the town by that way. The assault was to be made by the Americans in two divisions, under Brigadiers Sullivan and Greene, the whole to be commanded by Major-general Putnam. Circumstances prevented the execution of the plan, and January passed by without any decisive movement on the part of either army. The American forces, however, were daily augmenting, and they were less annoyed by the British cannon than they had been, for Howe was more sparing of powder than Gage. **

The Provincial Congress of Massachusetts, at its winter session, organized the militia of the province anew. John Hancock, James Warren, and Azor Orne were appointed major generals, and thirteen regiments were formed. A new emission of paper money, to a large amount, was authorized, and various measures were adopted to strengthen the Continental army. Early in February, ten of the militia regiments arrived in camp; large supplies of ammunition had been received; intense cold had bridged the waters with ice, and Washington was disposed to commence operations immediately and vigorously. He called a council February, 1776 war on 16th, to whom he communicated the intelligence, derived from careful returns, that the American army, including the militia, then amounted to a little more than seventeen thousand men, while that of the British did not much exceed five thousand fit for duty. Many of them were sick with various diseases, and the small-pox was making terrible havoc in the enemy's camp. *** Re-enforcements from Ireland, Halifax, and New York were daily expected by Howe, and the present appeared to be the proper moment to strike. But the council again decided against attempting an assault, on account of the supposed inadequacy of the undisciplined Americans for the task. They estimated the British forces at a much higher figure; considered the fact that they were double officered and possessed ample artillery, and that the ships in the harbor would do great execution upon an army on the ice, exposed to an enfilading fire. It was resolved, however, to bombard and cannonade the town as soon as a supply of ammunition should arrive, and that, in the mean time, Dorchester Heights and Noddle's Island (now East Boston) should be taken possession of and fortified. The commander-in-chief was disappointed at this decision, for he felt confident of success himself. "I can not help acknowledging," he said, in a letter February 18, 1776 to Congress, "that I have many disagreeable sensations on account of my situation; for, to have the eyes of the whole Continent fixed with anxious expectation of hearing of some great event, and to be restrained in every military operation for the want of the necessary means for carrying it on, is not very pleasing, especially as the means

* The Boyne, sixty-four guns; Preston, fifty guns; Scarborough, and another sloop, one of twenty and the other of sixteen guns, and the Mercury.

** From the burning of Charlestown to Christmas day, the enemy had fired more than two thousand shot and shells, one half of the former being twenty-four pounders. They hurled more than three hundred bombs at Plowed Hill, and one hundred at Lochraere's Point. By the whole firing on the Cambridge side they killed only seven men, and on the Roxbury side just a dozen!—Gordon, i., 418.

*** Quite a number of people, sick with this loathsome disease, were sent out of Boston; and General Howe was charged with the wicked design of attempting thus to infect the American army with the malady.

* Journals, iii., 194.

Condition of the British Troops in Boston.—A Farce and its Termination.—Bombardment of Boston.—Industry of the Patriots.

011used to conceal my weakness from the enemy conceal it also from our friends, and add to their wonder." In the midst of these discouragements Washington prepared for a bombardment.

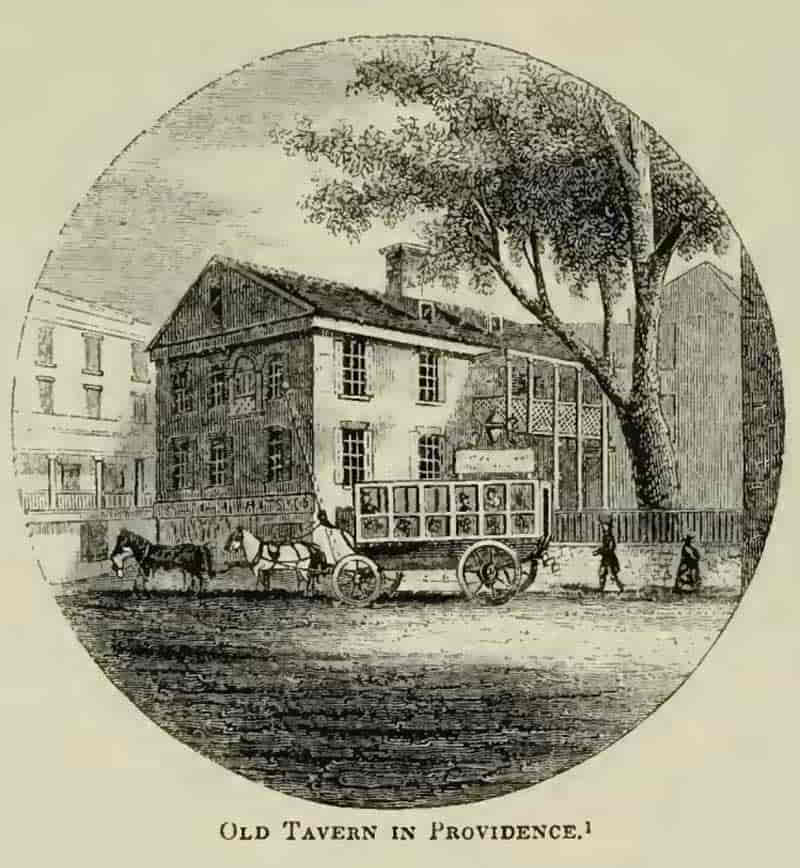

The British troops in Boston were beginning to be quite contented with their lot, and Howe felt almost as secure as if he was on the shores of Old England. He wrote to Dartmouth that he was under no apprehension of an attack from the rebels; and so confident were the Tories of the triumph of British arms, that Cecan Brush, a conceited and sycophantic Loyalist from New York, offered to raise a body of volunteers of three January 19, 1776 hundred men, to "occupy the main posts on the Connecticut River, and open a line of communication westward toward Lake Champlain," after "the subduction of the main body of the rebel force." * The enemy had also procured a plentiful supply of provisions, and the winter, up to the 1st of February, was tolerably mild. "The bay is open," wrote Colonel Moylan, from Roxbury. "Every thing thaws here except Old Put. He is still as hard as ever, crying out, 'Powder! powder! ye gods, give me powder!'" The British officers established a theater; balls were held, and a subscription had been opened for a masquerade, when Washington's operations suddenly dispelled their dream of security, and called them to lay aside the "sock and buskin," the domino, and the dancing-slipper, for the habiliments of real war. They had got up a farce called "Boston Blockaded they were now called to perform in the serio-comic drama of Boston bombarded, with appropriate costume and scenery.

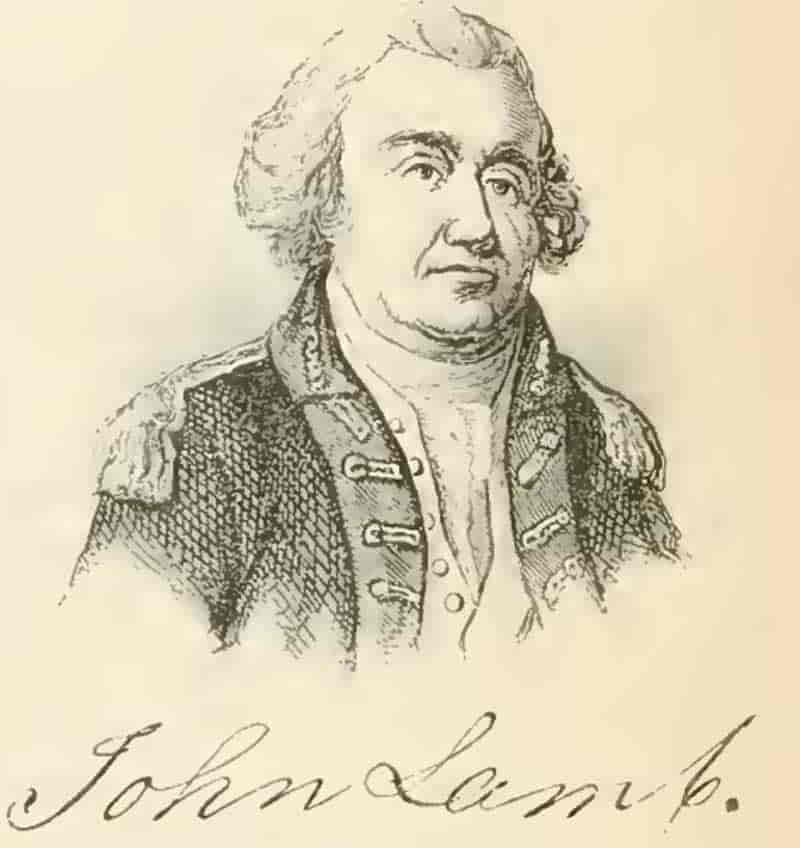

The design of Washington to fortify Dorchester Heights was kept a profound secret, and, to divert the attention of Howe, the Americans opened a severe bombardment and cannonade, on the night of the 2d of March, from the several batteries at Lechmere's Point, Roxbury, Cobble and Plowed Hills, and Lamb's Dam. Several houses in the city were shattered, and six British soldiers killed. The fire was returned with spirit, but with out serious effect. In the course of the bombardment, the Americans burst the "Congress" thirteen inch mortar, another of the same size, and three ten inch mortars.

On Sunday and Monday nights a similar cannonade was opened upon the city. March 3,4, 1776 At seven o'clock on Monday evening, General Thomas, with two thousand men, and intrenching tools, proceeded to take possession of Dorchester Heights. A train of three hundred carts, laden with fascines and hay, followed the troops. Within an hour, marching in perfect silence, the detachment reached the heights. It was separated into two divisions, and upon the two eminences already mentioned they commenced throwing up breastworks. Bundles of hay were placed on the town side of Dorchester Neck to break the rumble of the carts passing to and fro, and as a defense against the guns of the enemy, if they should be brought to bear upon the troops passing the Neck. Notwithstanding the moon was shining brightly and the air was serene, the laborers were not observed by the British sentinels. Under the direction of the veteran Gridley, the engineer at Bunker Hill, they worked wisely and well. Never was more work done in so short a time, and at dawn two forts were raised sufficiently high to afford ample protection for the forces within. They presented a formidable aspect to the alarmed Britons. Howe, overwhelmed with astonishment, exclaimed, "I know not what I shall do. The rebels have done more in one night than my whole army would have done in a month." They had done more than merely raise embankments; cannons were placed upon them, and they now completely commanded the town, placing Britons and Tories in the utmost peril.

* Frothingham; from manuscripts in the office of the Secretary of State of Massachusetts.

* This play was a burletta. The figure designed to represent Washington enters with uncouth gait, wearing a large wig, a long, rusty sword, and attended by a country servant with a rusty gun. While this farce was in course of performance on the evening of the 8th of January (1776), a sergeant entered suddenly, and exclaimed, "The Yankees are attacking our works on Bunker Hill!" The audience thought this was part of the play, and laughed immoderately at the idea; but they were soon undeceived by the voice of the burly Howe shouting, "Officers, to your alarm-posts!" The people dispersed in great confusion. The cause of the fright was the fact that Majors Knowlton, Carey, had crossed the mill-dam from Cobble Hill, and set fire to some houses in Charlestown occupied by British soldiers. They burned fight dwellings, killed one man, and brought off five prisoners.

Astonishment of the British.—Insecurity of the Fleet and Army.—Preparations for Bombarding Boston.

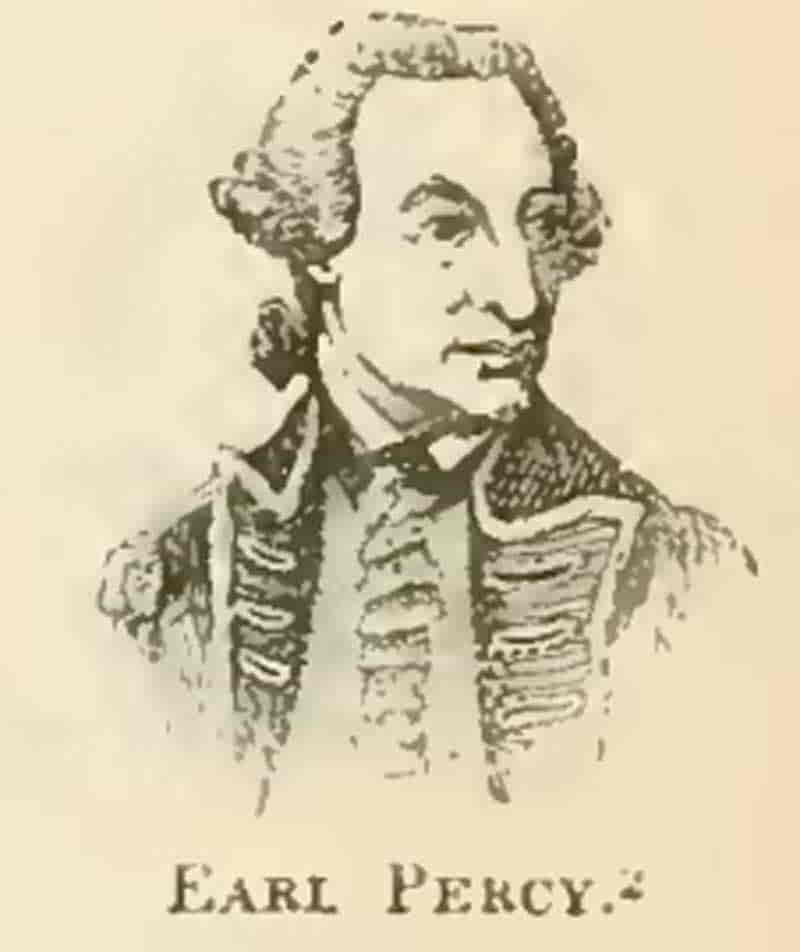

012The morning on which these fortresses were revealed to the enemy was the memorable 5th of March, the anniversary of the Boston Massacre. * The associations connected with the day nerved the Americans to more vigorous action, and they determined to celebrate and signalize the time by an act of retributive vengeance. Howe saw and felt his danger; and his anxiety was augmented when Admiral Shuldham assured him that the British fleet in the harbor must be inevitably destroyed when the Americans should get their heavy guns and mortars upon the heights. Nor was the army in the city secure. It was therefore resolved to take immediate measures to dislodge the provincials. Accordingly, two thousand four hundred men were ordered to embark in transports, rendezvous at Castle William, and, under the gallant Earl Percy, make an attack that night upon the rebel works. * Washington was made acquainted with this movement, and, supposing the attack was to be made immediately, sent a re-enforcement of two thousand men to General Thomas. Labor constantly plied its hands in strengthening the works. As the hills on which the redoubts were reared were very steep, rows of barrels, filled with loose earth, were placed outside the breastworks, to be rolled down upon the attacking column so as to break their ranks; a measure said to have been suggested by Mifflin. All was now in readiness. It was a mild, sunny day. The neighboring heights were crowded with people, expecting to see the bloody tragedy of Breed's Hill acted again. Washington himself repaired to the intrenchments, and encouraged the men by reminding them that it was the 5th of March. The commander-in-chief and the troops were in high spirits, for they believed the long-coveted conflict and victory to be near.

While these preparations were in progress on Dorchester Heights, four thousand troops, in two divisions, under Generals Sullivan and Greene, were parading at Cambridge, ready to be led by Putnam to an attack on Boston when Thomas's batteries should give the signal. They were to embark in boats in the Charles River, now clear of ice, under cover of three floating batteries, and, assaulting the city at two prominent points, to force their way to the works on the Neck, open the gates, and let in the troops from Roxbury.

Both parties were ready for action in the afternoon; but a furious wind that had arisen billowed the harbor, and rolled such a heavy surf upon the shore where the boats of the enemy were obliged to land, that it was unsafe to venture. During the night the rain came down in torrents, and a terrible storm raged all the next day. Howe abandoned his plan, and Washington, greatly disappointed, returned to his camp, leaving a strong force to guard the works on Dorchester Heights.

The situation of Howe was now exceedingly critical. The fleet and army were in peril, and the loyal inhabitants, greatly terrified, demanded that sure protection which Howe had March 1776 so often confidently promised. He called a council of officers on the 7th, when it was resolved to save the army by evacuating the town. This resolution spread great consternation among the Tories in the city, for they dreaded the just indignation of the patriots when they should return. They saw the power on which they had leaned as almost invincible growing weak, and quailing before those whom it had affected to despise. They well knew that severe retribution for miseries which they had been instrumental in inflicting, surely awaited them, when British bayonets should leave the peninsula and the excited patriots should return to their desolated homes. The dangers of a perilous voyage to a strange land seemed far less fearful than the indignation of the oppressed Americans, and the Loyalists resolved to brave the former rather than the latter. They began, therefore, to prepare for a speedy departure; merchandise, household furniture, and private property of every kind were crowded on board the ships. Howe had been advised by Dartmouth, in

* The day, usually observed in Boston, was now commemorated at Watertown, notwithstanding the exciting events occurring in the city and vicinity. The Reverend Peter Thacher delivered an oration on the occasion.—Bradford, 94.

** Three weeks previously, suspecting that the Americans were about to take possession of Dorchester Neck, Howe sent a detachment from Castle William, under Lieutenant-colonel Leslie, and some grenadiers and light infantry, under Major Musgrove, to destroy every house and other cover on the peninsula. They passed over on the ice, executed their orders, and took six of the American guard prisoners.

Condition of the Patriots in Boston.—Tacit Agreement to spare the Town.—Cannonade renewed.—Commission to plunder.

013November, to evacuate Boston, but excused himself by pleading that the shipping was inadequate. He was now obliged to leave with less, and, in addition to his troops, take with him more than one thousand refugee Loyalists, and their effects. Ammunition and warlike magazines of all kinds were hurried on board the vessels; heavy artillery, that could not be carried away, was dismounted, spiked, or thrown into the sea, and some of the fortifications were demolished. The number of ships and transports was about one hundred and fifty; but these were insufficient for the conveyance of the multitude of troops and inhabitants, their most valuable property, and the quantity of military stores to be carried away. *

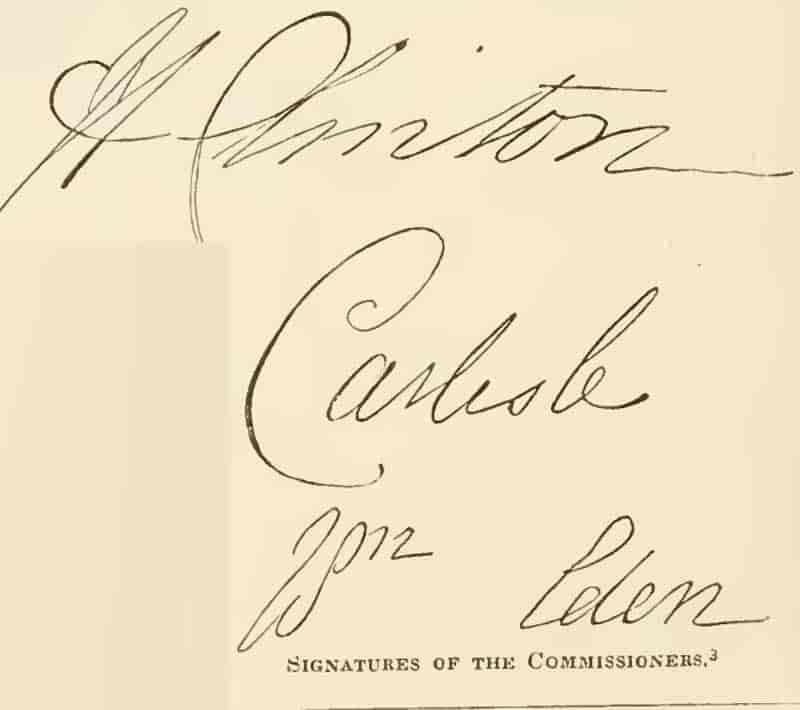

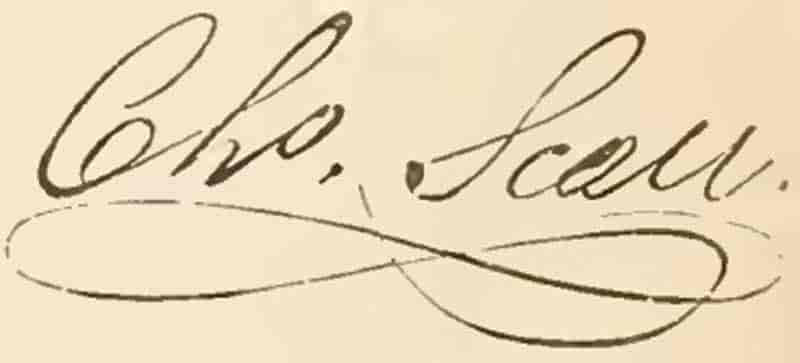

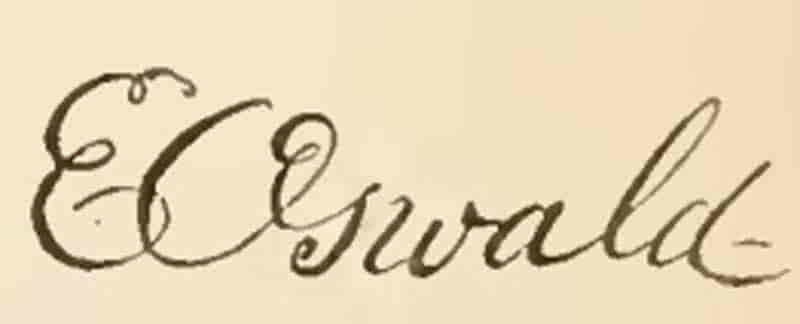

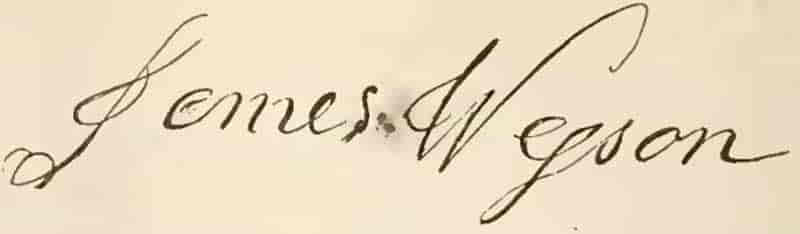

The few patriots who remained in Boston now felt great anxiety for the fate of the town. They saw the preparations for departure, and were persuaded that the enemy, smarting under the goadings of disappointed pride and ambition, would perform some signal act of vengeance before leaving—probably set fire to the city. ** Actuated by these surmises (which were confirmed by the threat of Howe that he would destroy the town if his army was molested in departing), and by the fearful array of ships which the admiral had arranged around the city, a delegation of the most influential citizens communicated with the British commander, through General Robertson. The conference resulted in a promise, on the part of Howe, that, if Washington would allow him to evacuate quietly, the town should be spared. A communication to this effect, signed by four leading men—John Scoliay, Timothy Newell, Thomas Marshall, and Samuel Austin—was sent to the camp at Roxbury without any special address. It was received by Colonel Learned, who carried it to Washington. The commander-in-chief observed, that as it was an unauthenticated paper, without an address, and not obligatory upon General Howe, he would take no notice of it. Learned communicated this answer to the persons through whom the address from Boston was received. Although entirely non-committal, it was received as a favorable answer, and both parties tacitly consented to the arrangement.

Washington, however, did not relax his vigilance, and continued his preparations for an assault upon Boston if the enemy did not speedily leave. A battery was placed near the water on Dorchester Neck on the 9th, to annoy the British shipping. On the same March 1776 night a detachment marched to Nooks' Hill, a point near the city completely commanding it, and planted a battery there. A fire imprudently kindled revealed their labor in progress to the enemy. A severe cannonade was immediately opened upon the patriots from the British batteries in the city. This was a signal for a general discharge of cannons and mortars from the various American batteries, and until dawn there was a continual roar of heavy guns. More than eight hundred shot were fired during the night. It was a fearful hour for the people of Boston, and all the bright anticipations of a speedy termination of the dreadful suspense in which for months they had lingered were clouded. But the belligerents were willing to avoid bloodshed. Washington determined to have possession of Boston at all events, but preferred to take it peaceably; while Howe, too cautious to risk a general action, and desirous of employing his forces in some quarter of the colonics where better success might be promised, withheld his cannonade in the morning, and hastened his preparations for evacuation.

And now a scene of great confusion ensued. Those who were about to leave and could not carry their furniture with them, destroyed it; the soldiers broke open and pillaged many stores; and Howe issued an order to Crean Brush, ** who had fawned at his feet ever since the siege began, to seize all clothing and dry goods not in possession of Loyalists, and place

* General Howe's official account.

** Congress gave Washington instructions in the Autumn to destroy Boston if it should be necessary to do so in order to dislodge the enemy. This instruction was given with the full sanction of many patriots who owned much property in the city. John Hancock, who was probably the largest property holder in Boston, wrote to Washington, that, notwithstanding such a measure would injure him greatly, he was anxious the thing should be done, if it would benefit the cause. Never were men more devoted than those who would be the greatest sufferers.

*** This order, which is dated March 10th, 1776, is in the office of the Secretary of State of Massachusetts, and bears Howe's autograph.—Frothingham.

Bad Conduct of the British Troops.—The Embarkation.—Entrance of the Americans into the City.—The Refugees.

014them on board two brigantines in the harbor. This authorized plunder caused great distress, for many of the inhabitants were completely stripped. Shops and dwellings were broken open and plundered, and what goods could not be carried away were wantonly destroyed.

These extremes were forbidden in general order the next day, but the prohibition March 12. was little regarded.

On the 15th, the troops paraded to march to the vessels, the inhabitants being ordered to remain in their houses until the army had embarked. An easterly breeze sprang up, and the troops were detained until Sunday, the 17th. In the mean while, they did much mischief by destroying and defacing furniture, and throwing valuable goods into the river. They acted more like demons than men, and had they not been governed by officers possessed of some prudence and honor, and controlled by a fear of the Americans, the town would doubtless have suffered all the horrors of sack and pillage.

Early on Sunday morning, the embarkation of the British army and of the Loyalists commenced. The garrison on Bunker Hill left it at about nine o'clock. Washington observed these movements, and the troops in Cambridge immediately paraded. Putnam with six regiments embarked in boats on the Charles River, and landed at Sewall's Point. The sentinels on Bunker Hill appeared to be at their posts, but, on approaching, they were observed to be nothing but effigies; not a living creature was within the British works. With a loud shout, that startled the retreating Britons, the Americans entered and took possession. When this was effected, the British and Tories had all left Boston, and the fleet that was to convey them away was anchored in Nantasket Roads, where it remained ten days. * A detachment of Americans entered the city, and took possession of the works and the military stores that were left behind. ** The gates on Boston Neck were unbarred, and General Ward, with five thousand of the troops at Roxbury, entered in triumph, Ensign Richards bearing the Union flag. General Putnam assumed the command of the whole, and in the name of the Thirteen United Colonies took possession of all the forts and other defenses which the a March 18, 1776 retreating Britons had left behind. (a) On the 20th, the main body of the army, with Washington at the head, entered the city, amid the joyous greetings of hundreds, who for ten months had suffered almost every conceivable privation and insult. Their friends from the country flocked in by hundreds, and joyful was the reunion of many families that had been separated more than half a year. On the 28th, a thanksgiving sermon was preached by the Reverend Dr. Elliot, from the words of Isaiah, "Look upon Zion, the city of our solemnities: thine eye shall, see Jerusalem a quiet habitation, a tabernacle that shall not be taken down: not one of the stakes thereof shall be removed, neither shall any of the cords thereof be broken." *** It was a discourse full of hope for the future, and con-

* The whole effective British force that withdrew, including seamen, was about eleven thousand. The Loyalists, classed as follows, were more than one thousand in number: 132 who had held official stations; 18 clergymen; 105 persons from the country; 213 merchants; 382 farmers, traders, and mechanics: total 924. These returned their names on their arrival at Halifax, whither the fleet sailed. There were nearly two hundred more whose names were not registered. It was a sorrowful flight to most of them; for men of property left all behind, and almost every one relied for daily food upon rations from the army stores. The troops, in general, were glad to depart. Frothingham (page 312) quotes from a letter written by a British officer while lying in the harbor. It is a fair exhibition of the feelings of the troops: "Expect no more letters from Boston; we have quitted that place. Washington played upon the town for several days. A shell which burst while we were preparing to embark did very great damage. Our men have suffered. We have one consolation left. You know the proverbial expression, 'Neither Hell, Hull, nor Halifax can afford worse shelter than Boston.' To fresh provision I have for many months been quite an utter stranger. An egg was a rarity. The next letter from Halifax."

** So crowded were the vessels with the Loyalists and their effects that Howe was obliged to leave some of his magazines. The principal articles which were left at Castle Island and Boston were 250 pieces of cannon, great and small; four thirteen and a half inch mortars; 2500 chaldrons of sea coal; 2500 bushels of wheat; 2300 bushels of barley; 600 bushels of oats; 100 jars of oil, containing a barrel each, and 150 horses. Some of the ordnance had been thrown into the water, but were recovered by the Americans. In the hospital at Boston a large quantity of medicine was left, in which it was discovered that white and yellow arsenic was mixed! The object ean be easily guessed.—Gordon, ii., 32.

*** Isaiah, xxxiii., 20.

Condition of Boston after the Evacuation.—Troops sent to New York.—Lingering of British Vessels.—Final Departure.

015firmed the strong faith of the hundreds of listeners in the final triumph of liberty in America.

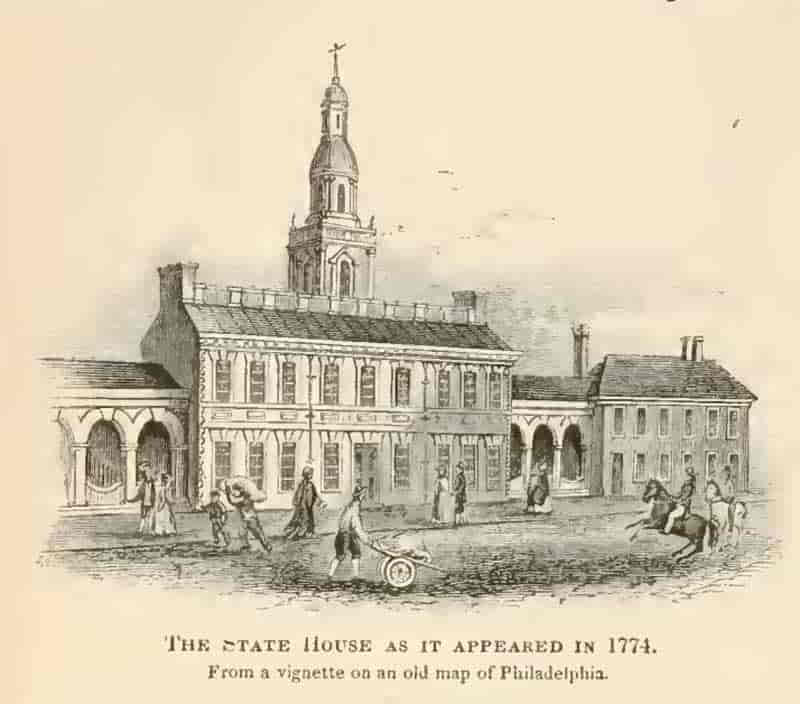

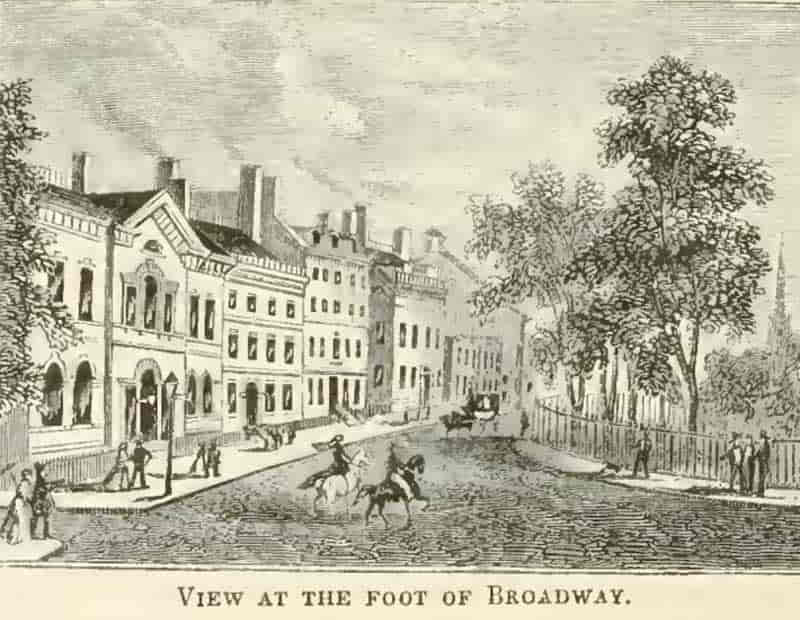

Sadness settled upon the minds of the people when the first outburst of joyous feeling had subsided, for Boston, the beautiful city—the metropolis of New England—was a desolation. Many of the finest houses were greatly injured; shade-trees were cut down; churches were disfigured; ornamental inclosures were broken or destroyed; and the public buildings were shamefully defaced. The spacious old South meeting-house, as we have seen, was changed into a riding-school; and in the stove that was put up within the arena were burned, for kindling, many rare books and manuscripts of Prince's fine library. The parsonage house belonging to this society was pulled down for fuel. The old North Chapel was demolished for the same purpose, and the large wooden steeple of the West Church was converted to the same use. Liberty Tree, noticed on page 466, vol. i., furnished fourteen cords of wood. Brattle Street and Hollis Street churches were used for barracks, and Faneuil Hall was converted into a neat theater. * A shot from the American lines, which struck the tower of Brattle Street Church, was picked up, and subsequently fastened at the point where it first struck, and there it remains.

Ignorant of the destination of Howe, and supposing it to be New York, Washington sent off five regiments, and a portion of the artillery, under General Heath, for that March 13, 1776 city. They marched to New London, where they embarked, and proceeded to New York through the Sound. On the departure of the main body of the British fleet from Nantasket Roads, Washington ordered the remainder of the army to New York, except five regiments, which were left for the protection of Boston, under General Ward. Sullivan marched on the 27th; another brigade departed on the 1st of April; and the last brigade, under Spencer, marched on the 4th. Washington, also, left Cambridge for New. York on that day. April 4

A portion of the British fleet, consisting of five vessels, still lingered in the harbor, and was subsequently joined by seven transports, filled with Highlanders. The people of Boston were under great apprehension of Howe's return. All classes of people assisted in building a fortification on Noddles Island (now East Boston) and in strengthening the other defenses. These operations were carried on under the general direction of Colonel Gridley. In May, Captain Mugford, of the schooner Franklin, a Continental cruiser, captured the British ship Hope, bound for Boston, with stores, and fifteen hundred barrels of powder. May 17 On the 19th, the Franklin and Lady Washington started on a cruise, but got aground at Point Shirly. Thirteen armed boats from the British vessels attacked them, and a sharp engagement ensued. Captain Mugford, while fighting bravely, received a mortal wound. His last words were those used nearly forty years afterward by Lawrence, "Don't give up the ship! You will beat them off!" And so they did. The cruisers escaped, and put to sea.

In June, General Lincoln proposed a plan for driving the British fleet from the harbor. It was sanctioned by the Massachusetts Assembly, and was put in execution on the 14th. He summoned the neighboring militia, and, aided by some of General Ward's regular troops, took post on Moon Island, Hoff's Neck, and at Point Anderton. A large force also collected at Pettick's Island, and Hull; and a detachment with two eighteen pounders and a thirteen inch mortar took post on Long Island. Shots were first discharged at the enemy from the latter point. The fire was briskly returned; but the commander, Commodore Banks, perceiving the perilous situation of his little fleet, made signals for weighing anchor. After blowing up the light-house, he spread his sails and went to sea, leaving Boston harbor and vicinity entirely free from an enemy, except in the few dissimulating Tories who lurked in secret places. Through a reprehensible want of foresight, no British cruisers were left in the vicinity to warn British ships of the departure of the troops and fleet. The consequence was, that several store-ships-from England soon afterward arrived, and, sailing into the harbor

* Frothingham, page 328.

Capture of Campbell and Store-ships.—Effect of the Evacuation of Boston.—Medal awarded to Washington

016without suspicion, fell into the hands of the Americans. In this way, Lieutenant-colonel Campbell and seven hundred men were made prisoners in June.

The evacuation of Boston diffused great joy throughout the colonies, and congratulatory addresses were received by Washington and his officers from various legislative bodies, assemblages of citizens, and individuals.

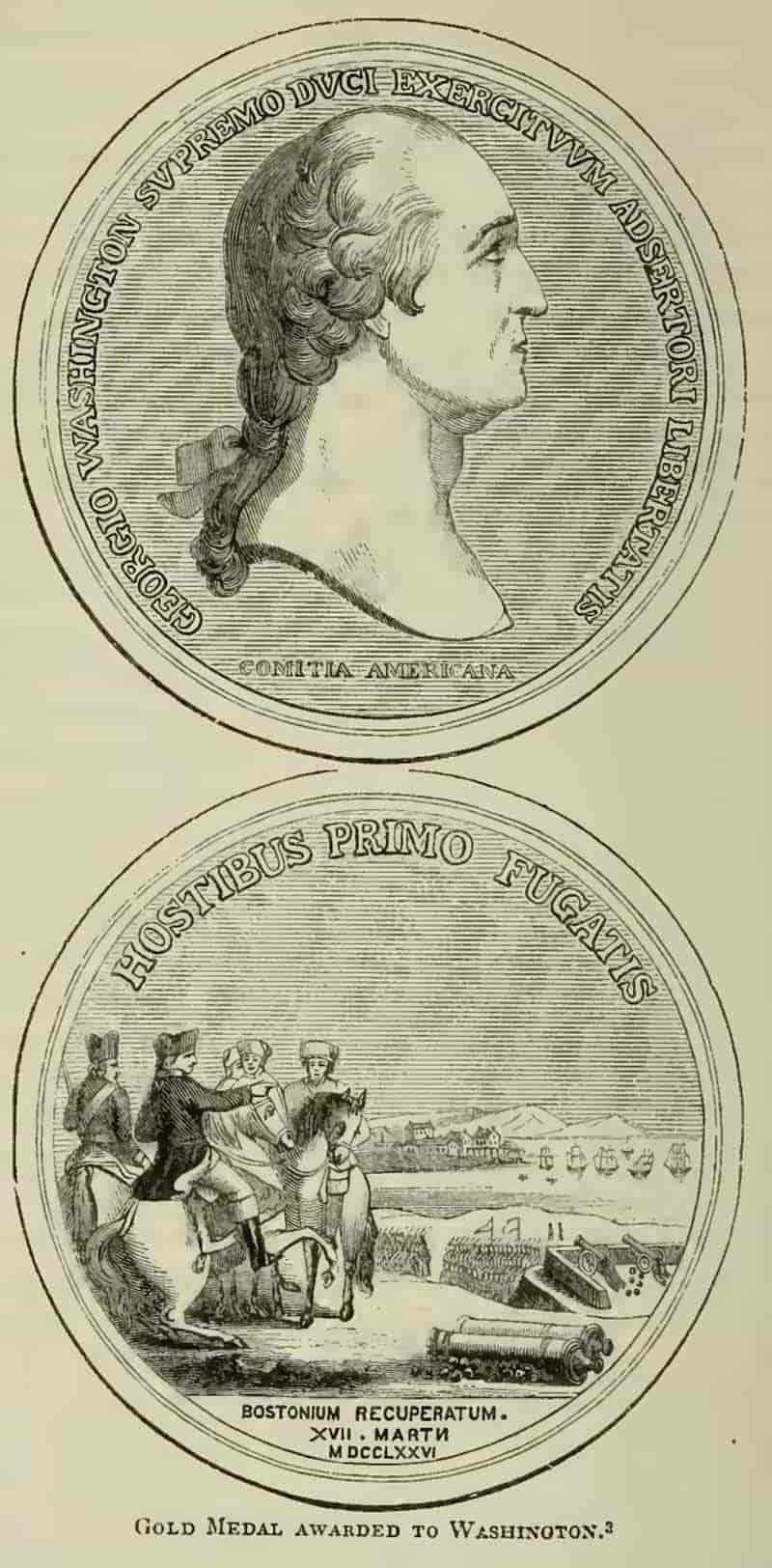

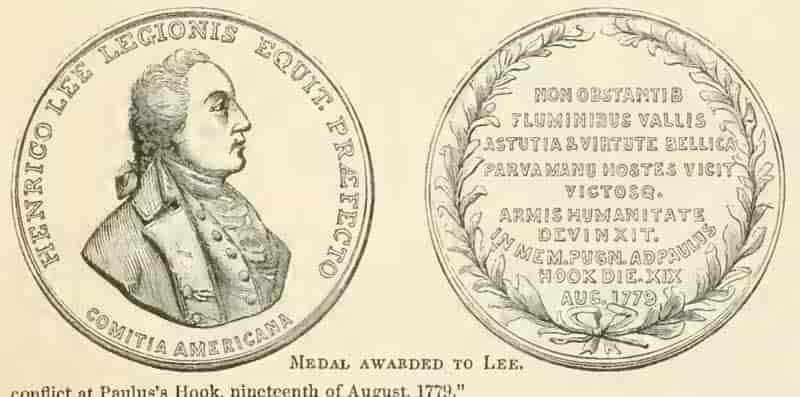

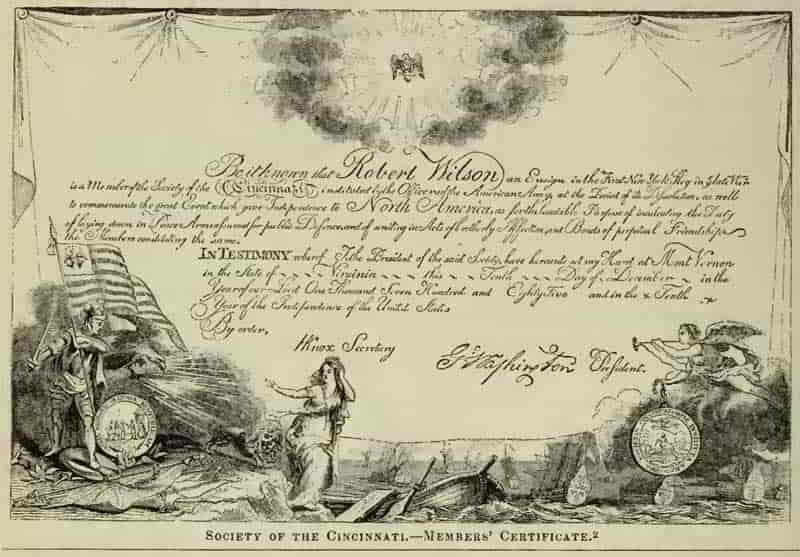

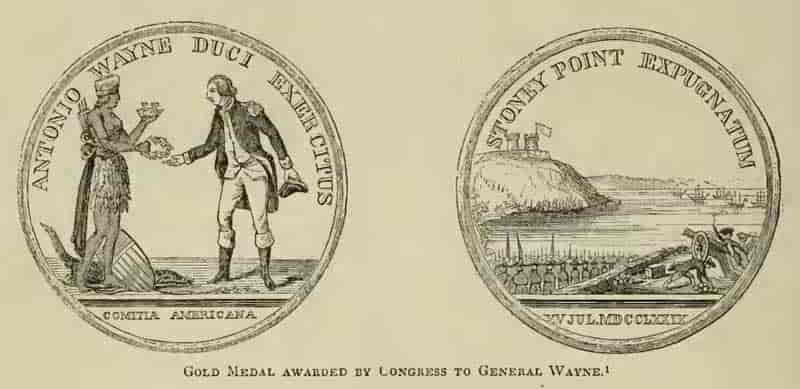

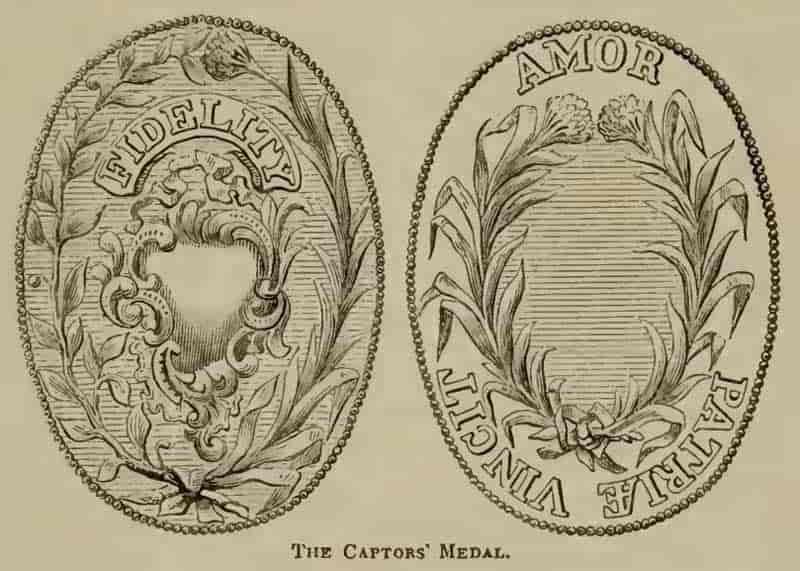

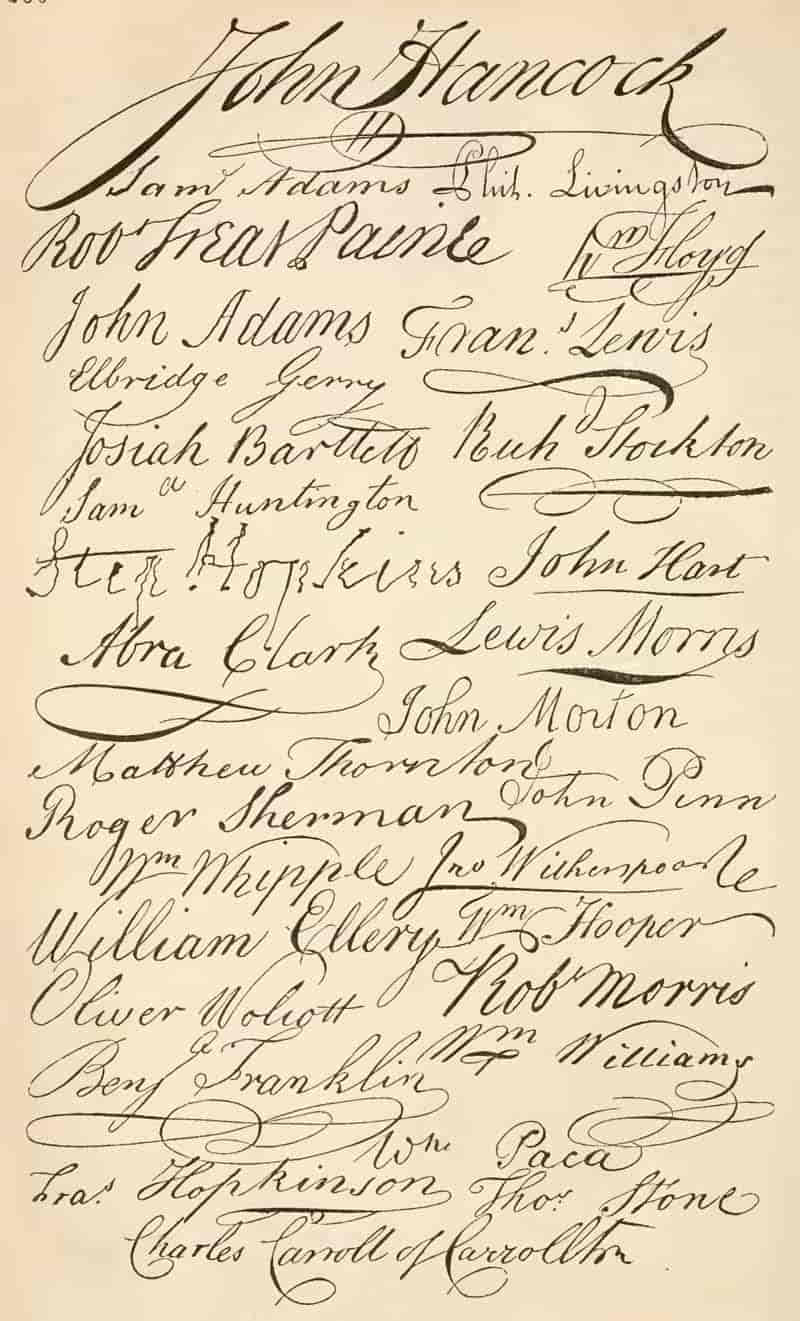

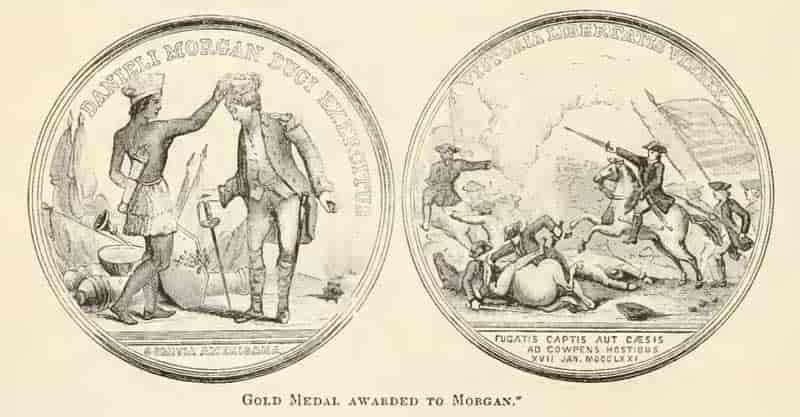

The Continental Congress received intelligence of the evacuation, by express, on the 25th of March, and immediately, on motion of John Adams, passed a vote of thanks to the commander-in-chief and the soldiers under his command, and also ordered a gold medal to be struck and presented to the general. John Adams, John Jay, and Stephen Hopkins were appointed a committee to prepare a letter of thanks and a proper device for the medal. *

The intelligence of this and other events at Boston within the preceding ten months produced great excitement in England, and attracted the attention of all Europe. The British Parliament exhibited violent agitations, and party lines began to be drawn almost as definitely among the English people, on American affairs, as in the colonies. In the spring, strong measures had been proposed, and some were adopted, for putting down the rebellion, and these had been met by counter action on the part of the American Congress. ** During the summer, John Wilkes, then Lord Mayor of London, and his party, raised a storm of indignation against government in the English capital. He presented a violent address to the king in the name of the livery of London,

* Journals of Congress, ii., 104.

** Congress issued a proclamation, declaring that "whatever punishment shall be inflicted upon any persons in the power of their enemies for favoring, aiding, or abetting the cause of American liberty, shall be retaliated in the same kind, and in the same degree, upon those in their power, who had favored, aided, or abetted, or shall favor, aid, or abet the system of ministerial oppression." This made the Tories and the British officers cautious in their proceedings toward patriots in their power.

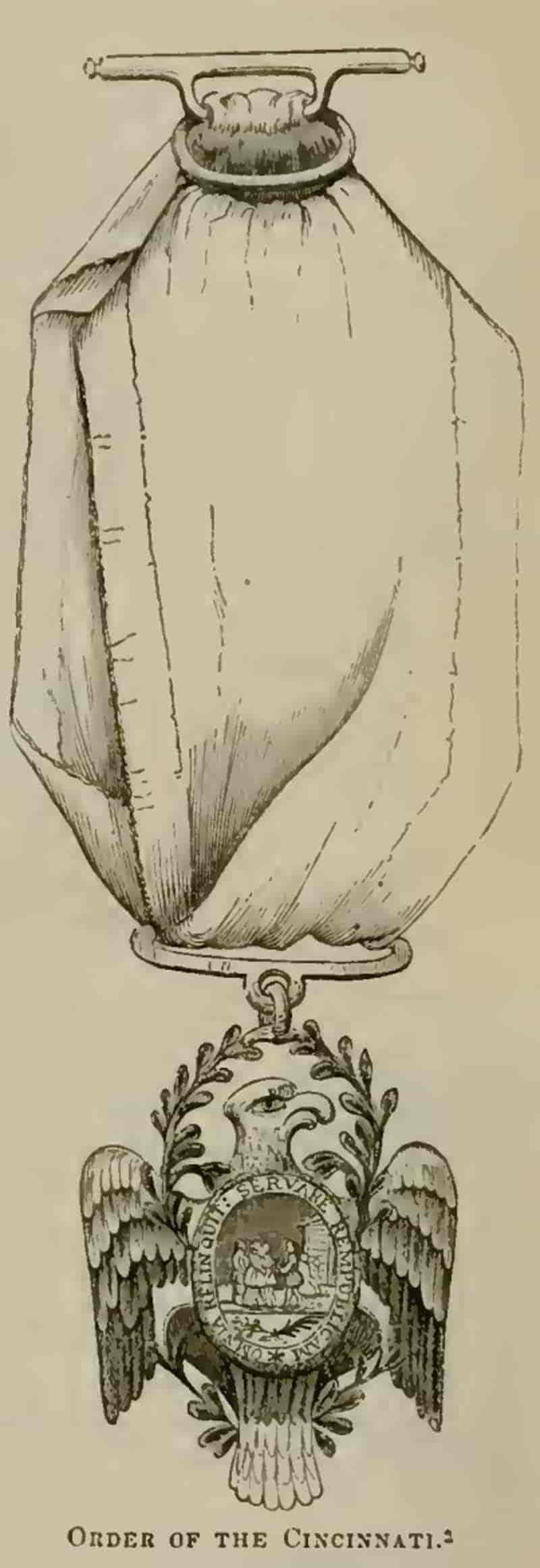

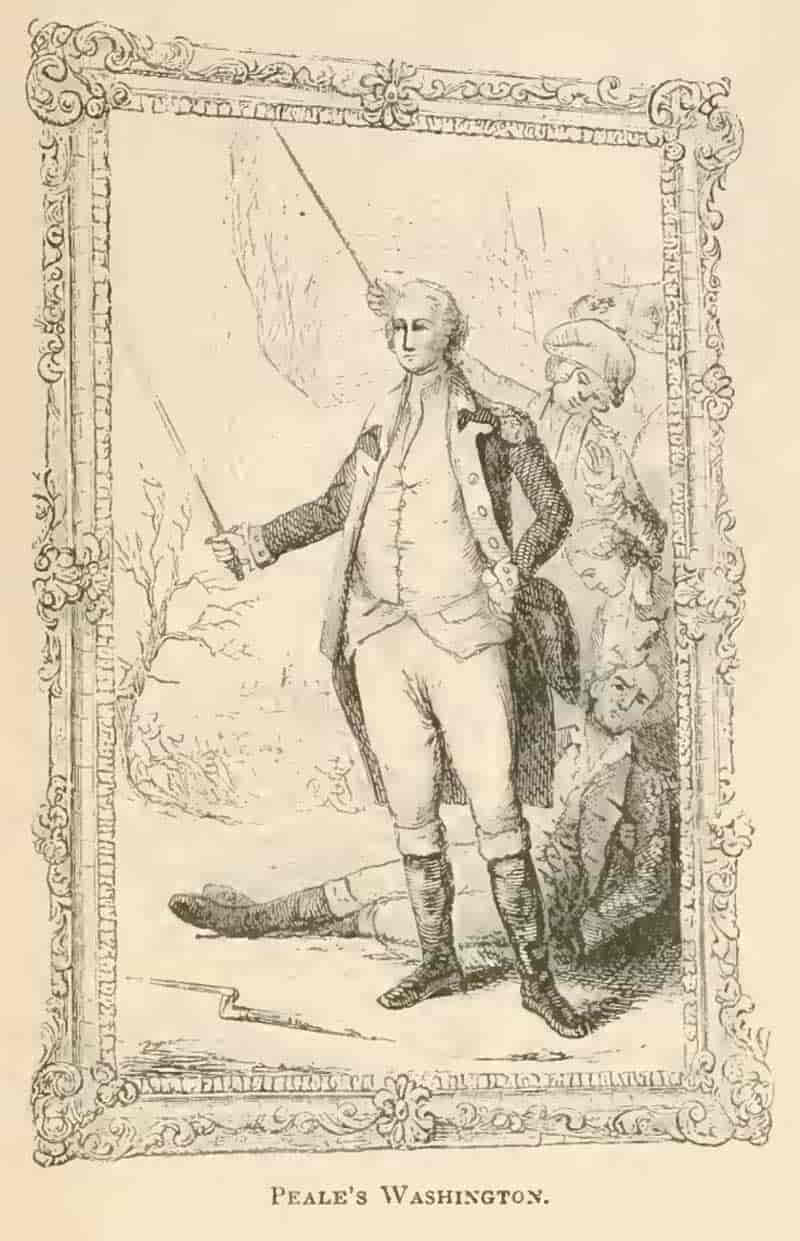

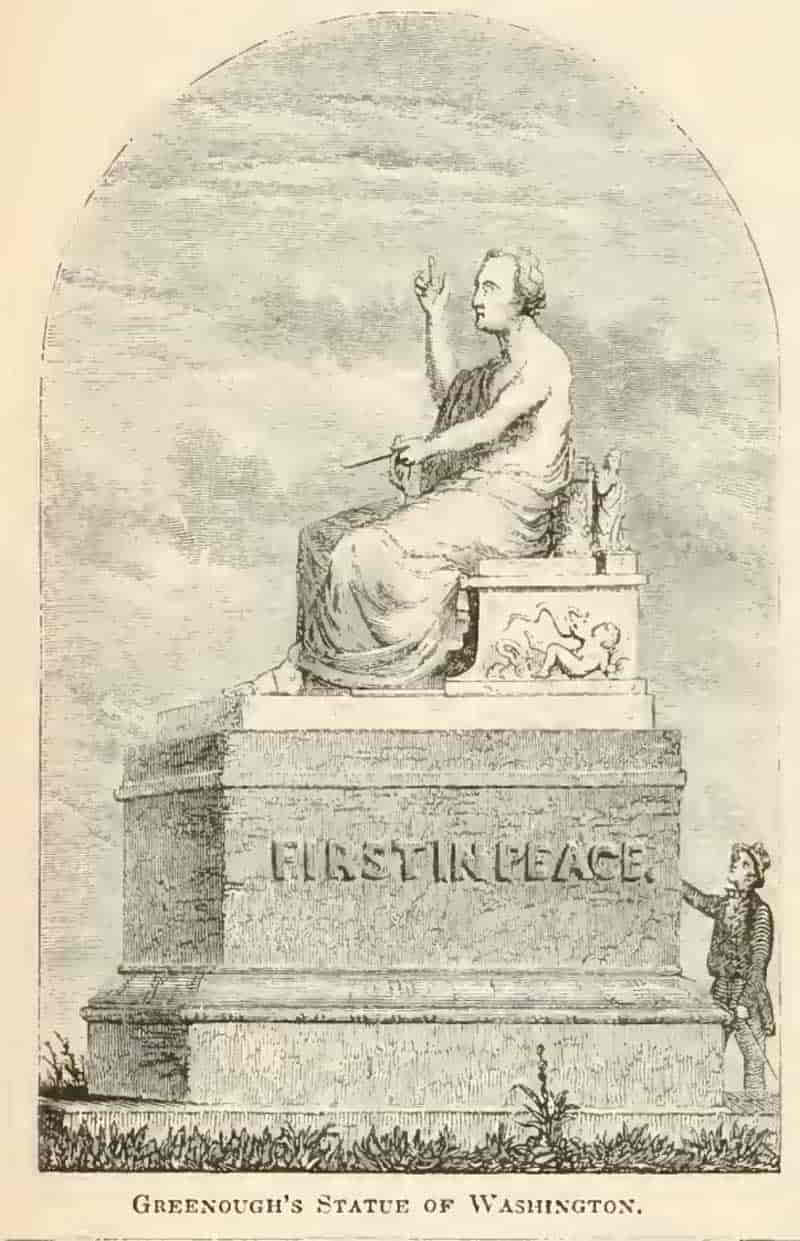

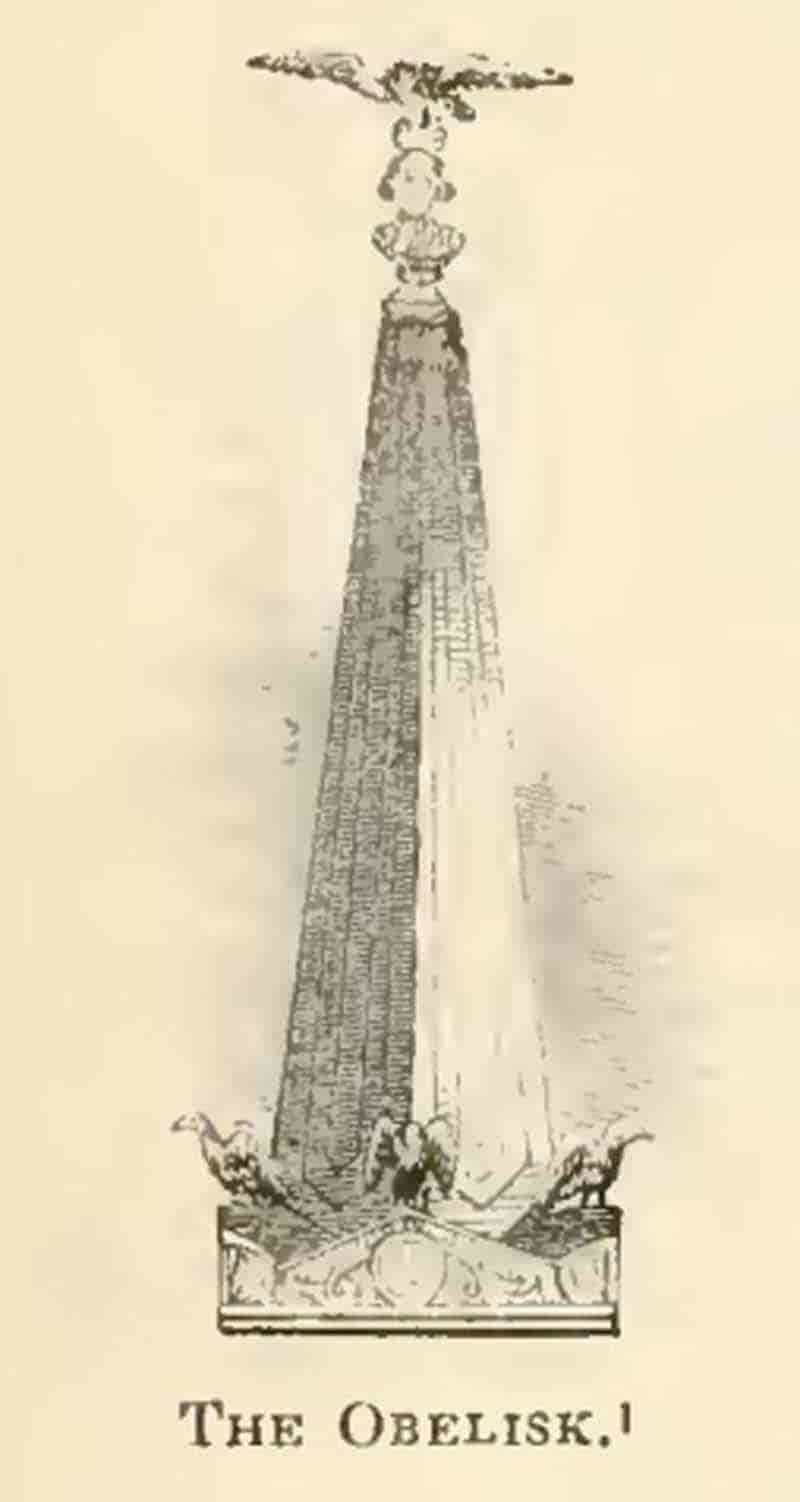

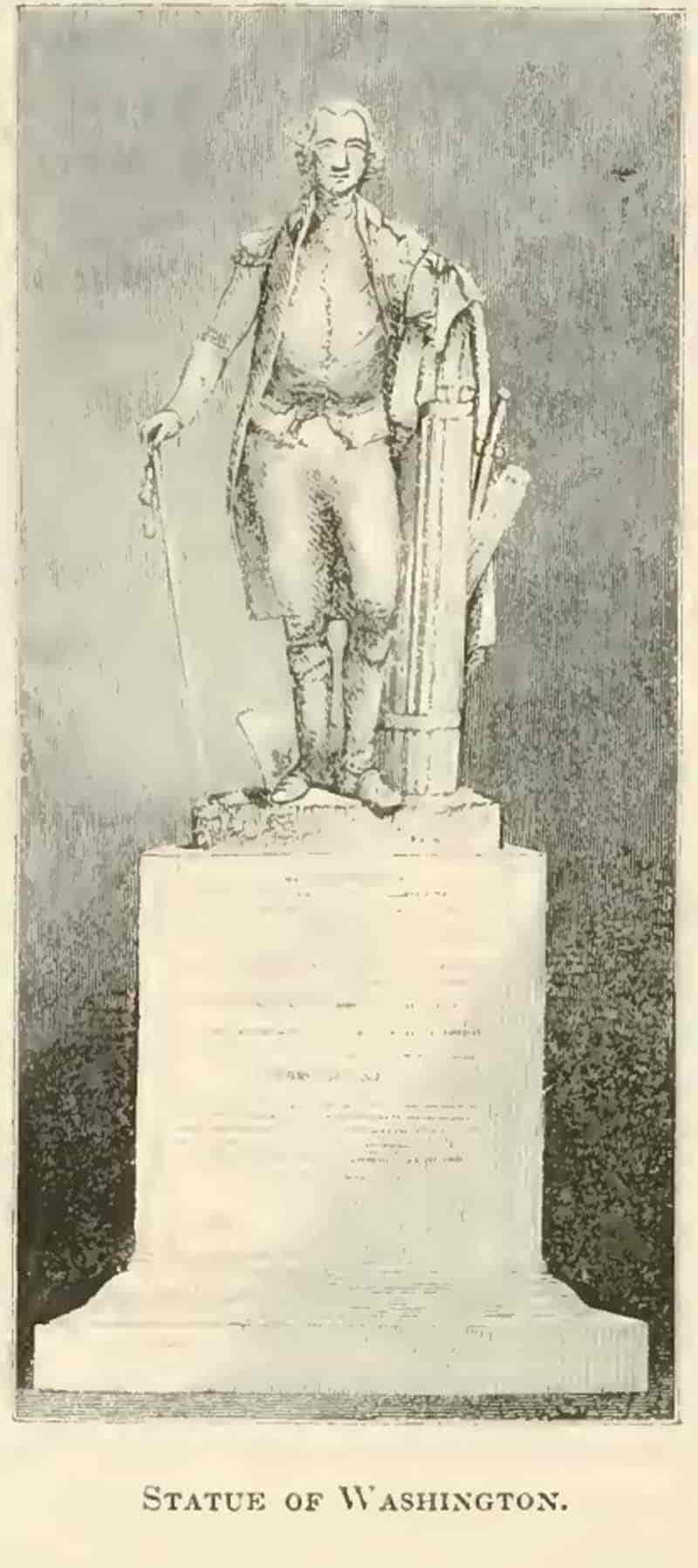

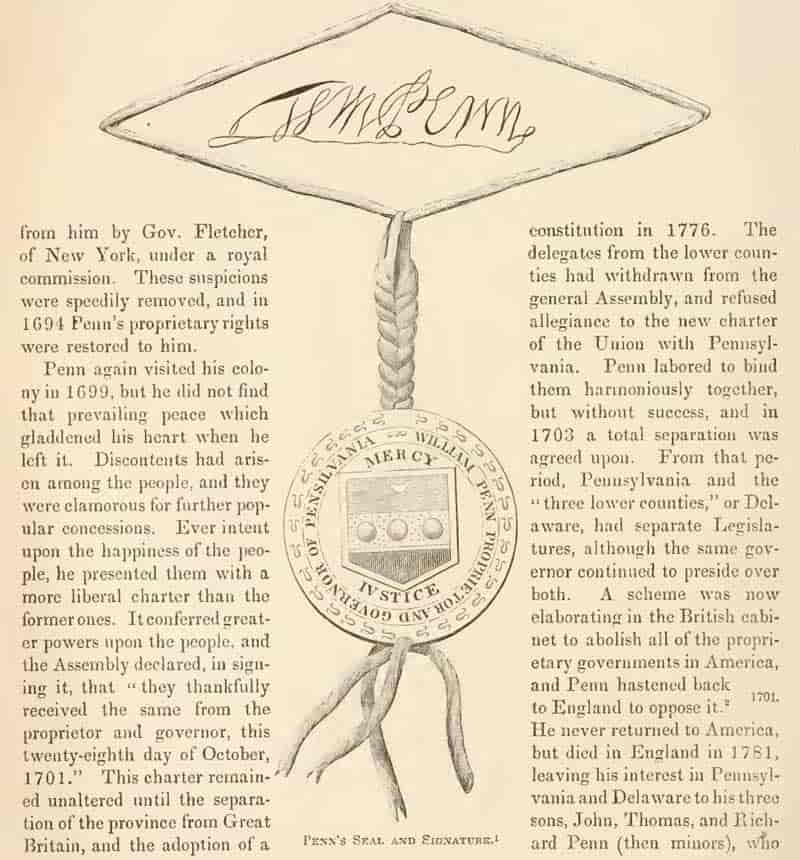

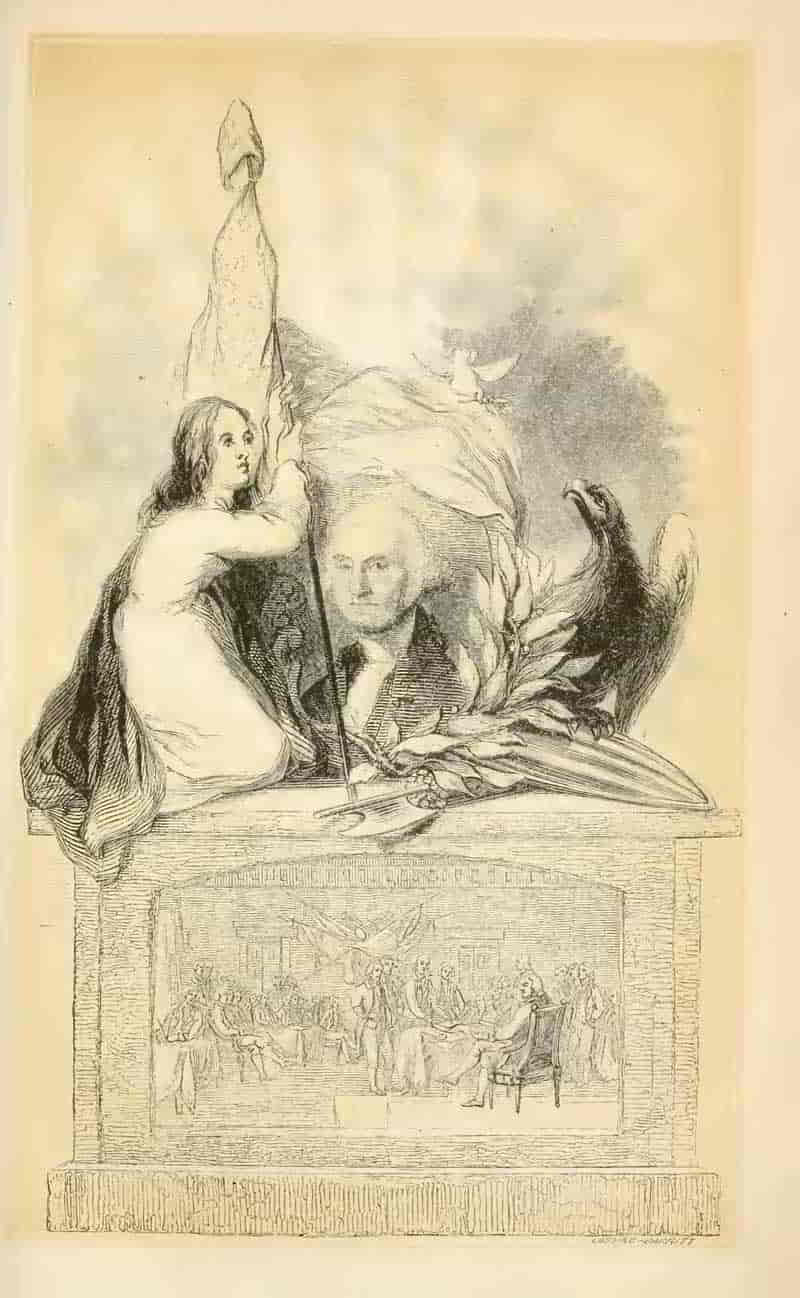

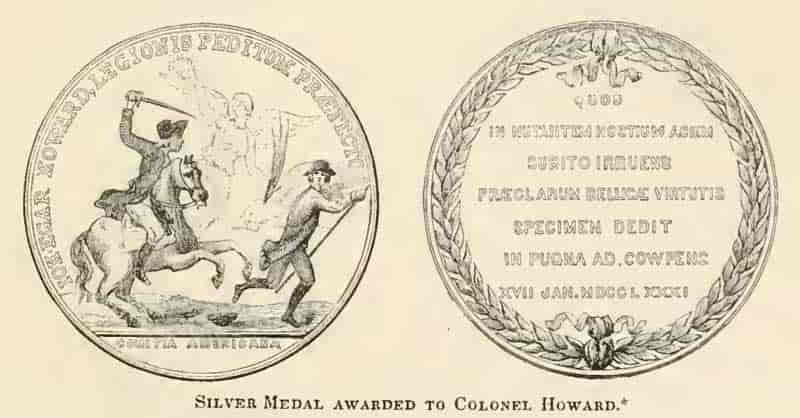

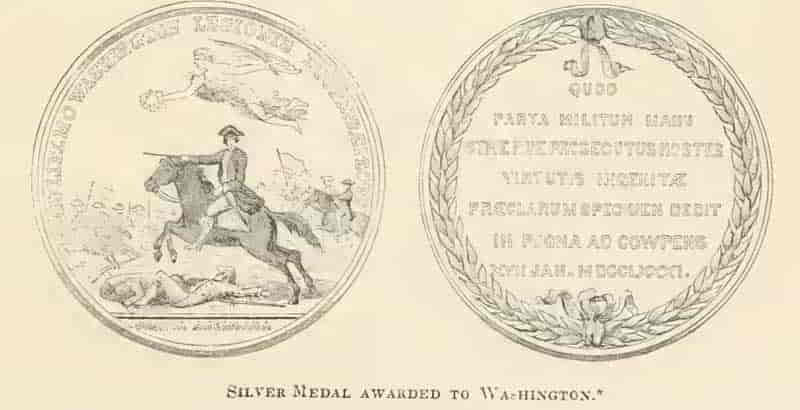

*** This drawing is the size of the medal. It was struck in Paris, from a die cut by Duvivier. The device is a head of Washington, in profile, with the Latin legend "Georgio Washington, supremo duci exercituum adsertori libertatis comitia Americana;" "The American Congress to George Washington, commander-in-chief of its armies, the assertors of freedom." Reverse: troops advancing toward a town; others marching toward the water; ships in view; General Washington in front, and mounted, with his staff, whose attention he is directing to the embarking enemy. The legend is "The enemy for the first time put to flight." The exergue under the device—"Boston recovered, 17th March, 1776."

Denunciations by John Wilkes.—The King tensed.—Boldness of the Common Council.—Governor Penn.—John Home Tooke

017in which it was asserted that it was plainly to be perceived that government intended to establish arbitrary rule in America without the sanction of the British Constitution, and that they were also determined to uproot the Constitution at home, and to establish despotism upon the ruins of English freedom. The address concluded by calling for an instant dismissal of the ministers. The king was greatly irritated, and refused to receive the address, unless presented in the corporate capacity of "mayor, aldermen, livery," &c. This refusal Wilkes denounced as a denial of the right of the city to petition the throne in any respectful manner it pleased; "a right," he said, "which had been respected even by the accursed race of Stuarts." Another address, embodying a remonstrance and petition, was prepared, and inquiry was made of the king whether he would receive it while sitting on the throne, it being addressed by the city in its corporate capacity. The king replied that he would receive it at his next levee, but not on the throne. One of the sheriffs sent by Wilkes to ask the question of his majesty, assured the king that the address would not be presented except when he was sitting upon the throne. The king replied that it was his prerogative to choose where he would receive communications from his subjects. The livery of London declared this answer to be a denial of their rights, resolved that the address and remonstrance should be printed in the newspapers, and that the city members in the House of Commons should be instructed to move for "an impeachment of the evil counselors who had planted popery and arbitrary power in America, and were the advisers of a measure so dangerous to his majesty and to his people as that of refusing to hear petitions." * The common council adopted a somewhat more moderate address and remonstrance, which the king received, but whether sitting upon the throne or at his levee is not recorded. **

On the 23d of August, the government, informed of the events of the 17th of June 1775at Charlestown, issued a proclamation for suppressing rebellion, preventing seditious correspondences, et cetera. Wilkes, as lord mayor, received orders to have this proclamation read in the usual manner at the Royal Exchange. He refused full obedience, by causing it to be read by an inferior officer, attended only by a common crier; disallowing the officers the use of horses, and prohibiting the city mace to be carried before them. The vast assembly that gathered to hear the reading replied with a hiss of scorn.

A few days afterward the respectful petition of the Continental Congress was laid before the king by Richard Penn. Earl Dartmouth soon informed Penn that the king had resolved to take no notice of it; and again the public mind was greatly agitated, particularly in London, at what was denominated "another blow at British liberty." The strict silence of ministers on the subject of this petition gave color to the charge that they had a line of policy marked out, from which no action of the Americans could induce them to deviate short of absolute submission. The Duke of Richmond determined to have this silence broken, and procured an examination of Governor Penn before the House of Lords. That examination brought to light many facts relative to the strength and union of the colonics which ministers would gladly have concealed. It revealed the truth that implicit obedience

* Pictorial History of England, v., 235.

** It was about this time that the celebrated John Horne Tooke, a vigorous writer and active politician, was involved in a proceeding which, in November, 1775, caused him to receive a sentence of imprisonment for one year, pay a fine of one thousand dollars, and find security for his good behavior for three years. His alleged crime was "a libel upon the king's troops in America." The libel was contained in an advertisement, signed by him, from the Constitutional Society (supposed to be revolutionary in its character), respecting the Americans. That society called the Lexington affair a "murder" and agreed that the sum of five hundred dollars should be raised "to be applied to the relief of the widows, orphans, and aged parents of our beloved American fellow-subjects" who had preferred death to slavery. This was a set-off against subscriptions then being raised in England for the widows and orphans of the British soldiers who had perished. The sum raised by this society was sent to Dr. Franklin, who, as we have seen, paid it over to the proper committee, when he visited the army at Cambridge, in October, under the direction of Congress. Out of the circumstance of Horne Tooke's imprisonment arose his letter to Counselor Dunning, which formed the basis of his subsequent philological work, The Diversions of Purley, published in 1780.

Strength of the Americans.—Political Change in the London Common Council.—Persecution of Stephen Sayre.

018to Congress was paid by all classes of men; that in Pennsylvania alone there were twenty thousand effective men enrolled for military service, and four thousand minute men; that the Pennsylvanians perfectly understood the art of making gunpowder; that the art of casting cannon had been carried to great perfection in the colonies; that small arms were also manufactured in the best manner; * that the language of Congress was the voice of the people; that the people considered the petition as an olive branch; and that so much did the Americans rely upon its effect, that if rejected, or treated with scorn, they would abandon all hope of a reconciliation.

On the 11th of October an address, memorial, and petition, signed by eleven hundred and seventy-one "gentlemen, merchants, and traders of London," was laid before his majesty, in which it was charged that all the troubles in America, and consequent injury to trade, arose from the bad policy pursued by Parliament; and the new proposition which had just leaked out, to employ foreign soldiers against the Americans, was denounced in unmeasured terms. A counter petition, signed by nine hundred and twenty citizens of London, was presented three days afterward, in which the conduct of the colonists was severely censured. This was followed by another on the same side, signed by ten hundred and twenty-nine persons, including the livery of London, who, a few months previously, under Wilkes, had spoken out so boldly against government. This address glowed with loyalty to the king and indignation against the rebels! Like petitions from the provincial towns, procured by ministerial agency, came in great numbers, and the government, feeling strengthened at home, contemplated the adoption of more stringent measures to be pursued in America. Suspected persons in England were closely watched, and several were arraigned to answer various charges against them. ** Lord North became the idol of the government party, and, in addition to bein feted by the nobility, and thoroughly bespattered with fulsome adulation by corporate bodies and the ministerial press, the University of Oxford had a medal struck in his honor.

Parliament assembled on the 26th of October, much earlier than common, on account of the prevalent disorders. The king, in his speech at the opening, *** after mentioning the rebellious position of the American colonies, expressed (as he had done before) his determination to act decisively. He alleged that the course of government hitherto had been moderate and forbearing! but now, as the rebellion seemed to be general, and the ob-

* I have in my possession a musket manufactured here in 1774, that date being engraved upon the breech. It is quite perfect in its construction. It was found on the battle field of Hubbardton, in Vermont, and was in the possession of the son of an American officer (Captain Barber) who was in that action. See page 146, of this volume.

** On the 23d of October (1775), Stephen Sayre, a London banker, an American by birth, was arrested on a charge of high treason, made against him by a sergeant in the Guard (also a native of America), named Richardson. He charged Sayre with having asserted that he and others intended to seize the king on his way to Parliament, to take possession of the town, and to overturn the present government. Sayre was known to be a friend to the patriots, and on this charge Lord Rochford, one of the secretaries of state, caused his papers to be seized and himself to be arrested. Sayre was committed to the Tower, from which he was released by Lord Mansfield, who granted a writ of habeas corpus. Sayre was subsequently tried and acquitted. He prosecuted Lord Rochford for seizing his papers, and the court awarded him a conditional verdict of five thousand dollars damages. The conditions proved a bar to the recovery of the money, and Sayre was obliged to suffer a heavy pecuniary loss in costs, besides the personal indignity.

*** This is the speech alluded to in the beginning of this chapter, which the British officers in Boston supposed had produced a determination on the part of the Americans to submit

Tenor of the King's Speech.—His false-Hopes.—Warm Debates in Parliament—Duke of Grafton in opposition.

019jects of the insurgents an independency of empire, they must be treated as rebels. He informed Parliament that he had increased the naval establishment, and greatly augmented the land forces, "yet in such a maimer as to be least expensive or burdensome to the kingdom." This was in reference to the employment of German troops, which I shall presently notice. He professed a desire to temper his severity with mercy, and for this purpose proposed the appointment of commissioners to offer the olive branch of peace and pardon to all offenders among "the unhappy and deluded multitude" who should sue for forgiveness, as well as for whole communities or provinces. He also expressed a hope that his friendly relations with other European governments would prevent any interference on their part with his plans. *

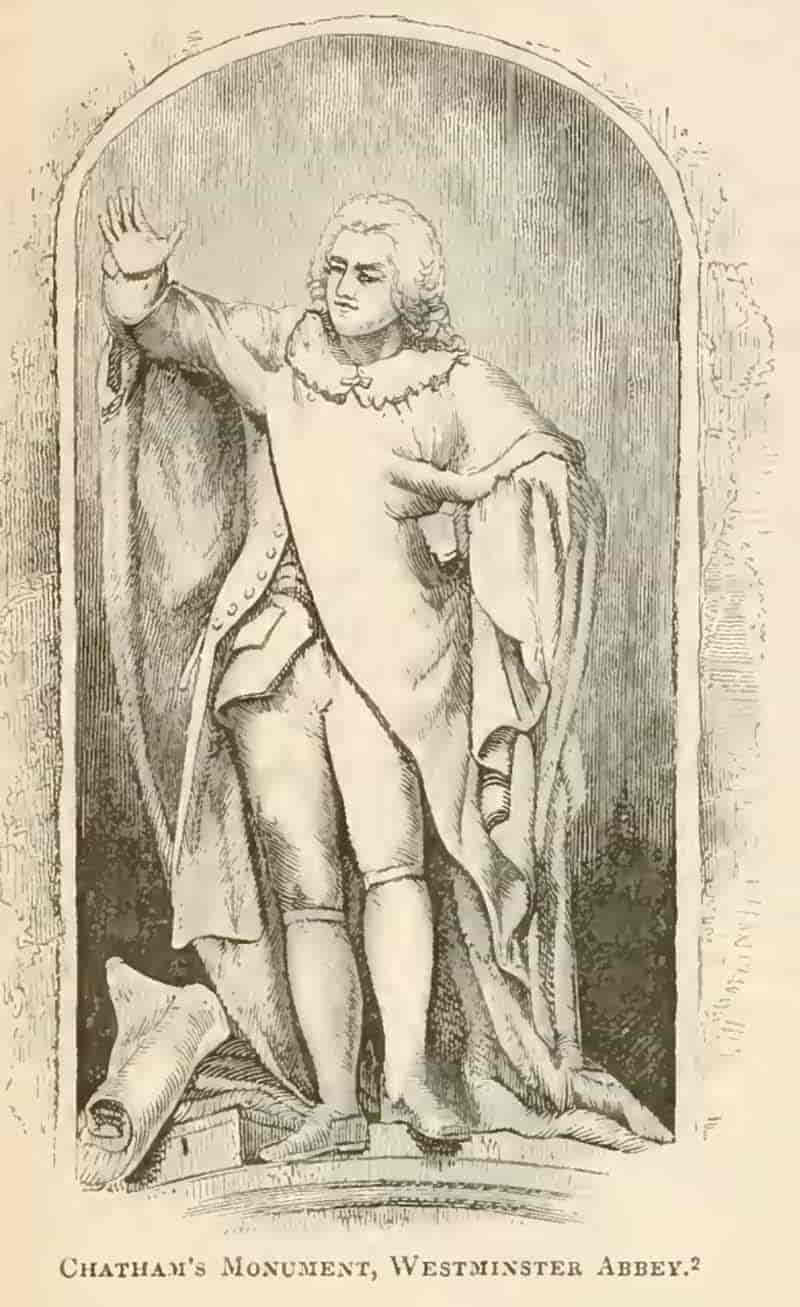

The address of Parliament responsive to the king's speech was, of course, but an echo of that document. It was firmly opposed by all the old leaders of opposition, and the management of the summer campaign in America was severely commented upon. Ministers were charged with placing their sovereign in a most contemptible position before the world, and with wresting from him the scepter of colonial power in the West. "They have acted like fools in their late summer campaign," said Colonel Barré. "The British army at Boston," he said, "is a mere wen—an excrescence on the vast continent of America. Certain defeat awaits it. Not the Earl of Chatham, nor Frederic the Great, nor even Alexander the Great, ever gained so much in one campaign as ministers have lost."

"They have lost a whole continent," said Fox; and at the same time he characterized North as "the blundering pilot who had brought the vessel of state into its present difficulties."

"It is a horrible idea, that the Americans, our brethren, shall be brought into submission to ministerial will by fleets and armies," said General Conway; and other members were equally severe upon ministers. In the Upper House, the Duke of Grafton, Lords Shelburne, Camden, Richmond, Gower, and Cavendish, and the Marquis of Rockingham, took decided ground against ministers. Chatham was very ill, and could not leave his country seat. The Duke of Grafton, one of the minority, was bold in his denunciations, and in the course of an able speech declared that he had been greatly deceived in regard to the Americans, and that nothing short of a total repeal of every act obnoxious to the colonists passed since 1763 could now restore peace. The Cabinet, of course, did not concur with his grace, and he resigned the seals of office, and took a decided stand with the opposition. ** Dr. Hinchcliffe, bishop of Peterborough, followed Grafton, and also became identified with the opposition. Thurlow and Wedderburne were North's chief supporters. The address was carried in both houses by large majorities.

Burke again attempted to lead ministers into a path of common sense and common justice, by proposing a conciliatory bill. It included a proposition to repeal the November 16, 1775 Boston Port Bill; a promise not to tax America; a general amnesty; and the calling of a Congress by royal authority for the adjustment of remaining difficulties. North was rather pleased with the proposition, for he foresaw heavy breakers ahead in the course

* The king did not reckon wisely when he relied upon the implied or even expressed promises of nonintervention on the part of other powers. He had made application to all the maritime powers of Europe to prevent their subjects from aiding the rebel colonics by sending them arms or ammunition; and they all professed a friendship for England, while, at the same time, she was the object of their bitterest jealousy and hate, on account of her proud commercial eminence and political sway. The court of Copenhagen (Denmark) had issued an edict on the 4th of October against carrying warlike articles to America. The Dutch, soon afterward, took similar action; the punishment for a violation of the edict being a fine of only four hundred and fifty dollars, too small to make shipping merchants long hesitate about the risk where such enormous profits were promised. In fact, large quantities of gunpowder were soon afterward shipped to America from the ports of Holland in glass bottles invoiced "gin." France merely warned the people that what they did for the Americans they must do upon their own risk, and not expect a release from trouble, if they should get into any, by the French admiralty courts. Spain flatly refused to issue any order.

** His office of Lord of the Privy Seal was given to Lord Dartmouth, and the office of that nobleman was filled hy his opponent, Lord George Germaine—"the proud, imperious, unpopular Sackville." Germaine had taken an active part in favor of all the late coercive measures, and he was considered the fit instrument to carry out the plans of government toward the Americans, in the capacity of Colonial Secretary.

The Colonies placed under Martial Law.—Augmentation of the Army and Navy.—Proposition to employ foreign Troops

020of the vessel of state; but he had abhorred concession, and this appeared too much like it. A large majority voted against Burke's proposition.

November 22 Lord North introduced a bill a few days afterward, prohibiting all intercourse or trade with the colonies till they should submit, and placing the whole country under martial law. This bill included a clause, founded upon the suggestion in the king's speech, to appoint resident commissioners, with discretionary powers to grant pardons and effect indemnities. * The bill was passed by a majority of one hundred and ninety-two to sixty-four in the Commons, and by seventy-eight to nineteen in the House of Lords. Eight peers protested. It became a law by royal assent on the 21st of December.

Having determined to employ sufficient force to put down the rebellion, the next necessary step was to procure it. The Committee of Supply proposed an augmentation of the navy to twenty-eight thousand men, and that eighty ships should be employed on the American station: The land forces necessary were estimated at twenty-five thousand men. The king, as Elector of Hanover, controlled the troops of that little kingdom. Five regiments of Hanoverian troops were sent to Gibraltar and Minorca, to allow the garrisons of English troops there to be sent to America. It was also proposed to organize the militia of the kingdom, so as to have an efficient force at home while the regulars should go across the Atlantic. For their support while in actual service it was proposed to raise the land-tax to four shillings in the pound. This proposition touched the pockets of the country members of Parliament, and cooled their warlike ardor very sensibly.

The peace establishment at home being small, it was resolved, in accordance with suggestions previously made, to employ foreign troops. The king wrote an autograph letter to the States General of Holland, soliciting them to dispose of their Scotch brigade for service against the Americans. The request was nobly refused. A message was sent to the Parliament of Ireland requesting a supply of troops; that body complied by voting four thousand men for the American service. They servilely agreed to send men to butcher their brethren and kinsmen for a consideration; while the noble Hollanders, with a voice of rebuke, dissented, and refused to allow their soldiers to fight the strugglers for freedom, though strangers to them in blood and language. **

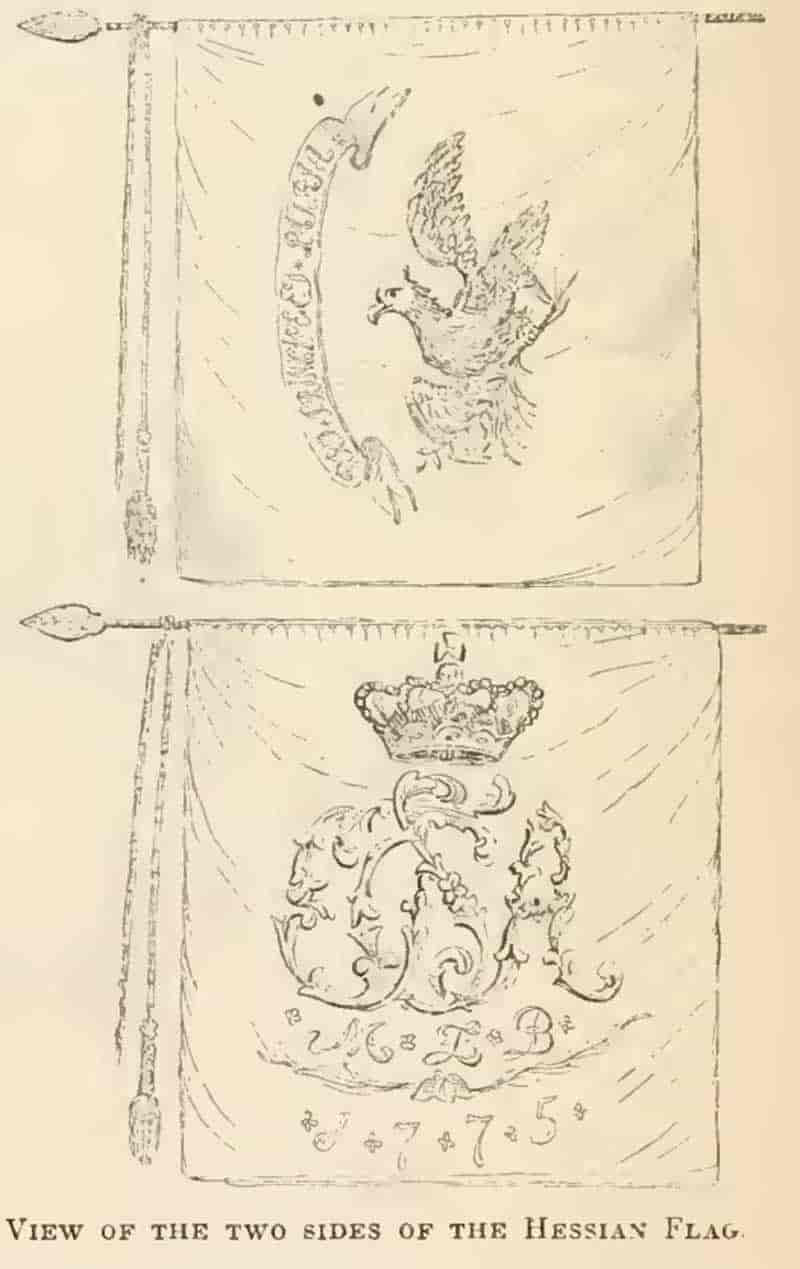

The king was more successful with some of the petty German princes. He entered into a treaty with the Landgrave of Hesse-Cassel, the Duke of Brunswick, the Prince of Hesse, and the Prince of Waldeck, for seventeen thousand men, to be employed in America. On the 29th of February, 1776, Lord North moved "that these treaties be referred to the Committee of Supply." A most vehement debate ensued in the House of Commons. Ministers pleaded necessity and economy as excuses for such a measure. "There was not time to fill the army with recruits, and hired soldiers would be cheaper in the end, for, after the war, if native troops were employed, there would be nearly thirty battalions to claim half pay." Such were the ostensible reasons; the real object was, doubtless, not so much economy, as the fear that native troops, especially raw recruits, unused to the camp, might affiliate with the insurgents. The opposition denounced the measure as not merely cruel toward the Americans, but disgraceful to the English name; that England was degrading herself by applying to petty German princes for succors against her own subjects; and that nothing would so effectually bar the way for reconciliation with the colonists as this barbarous prep-

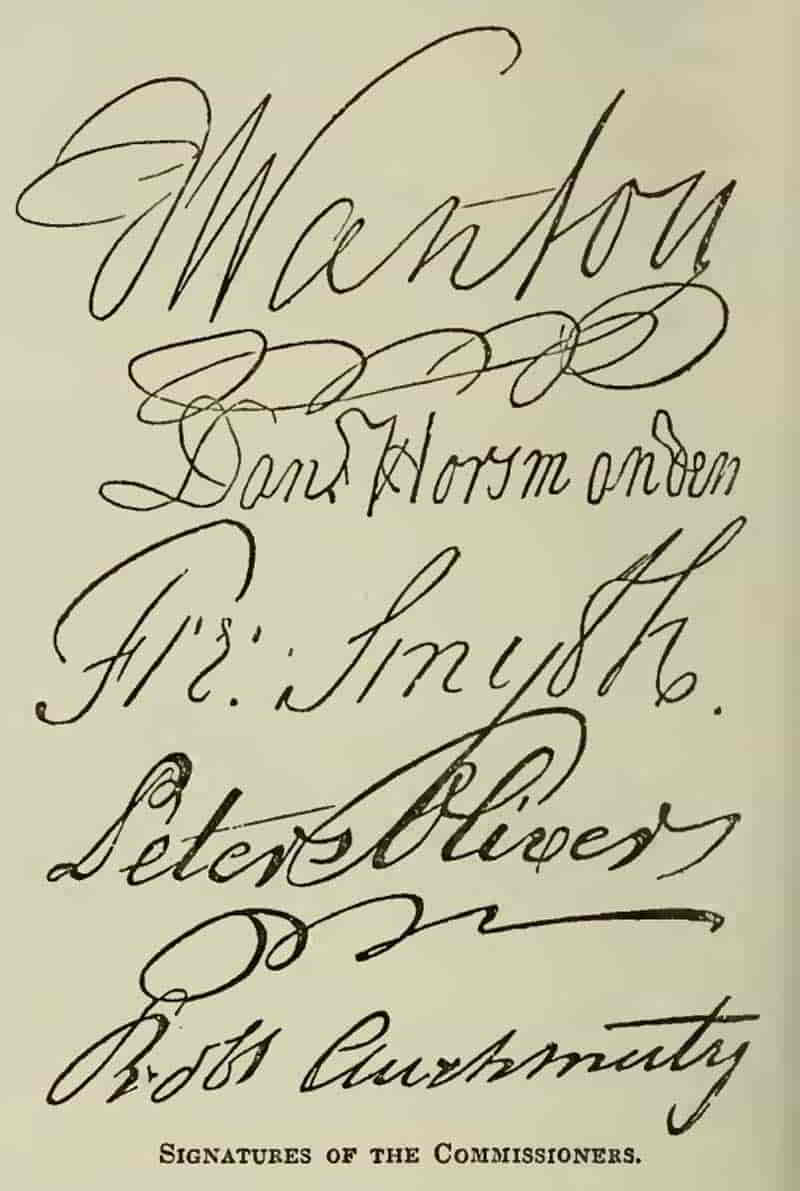

* This bill became a law, and under that clause General Howe, and his brother, Lord Howe, were appointed commissioners.

** can not forbear quoting the remarks of John Derk van der Chapelle, in the Assembly of the States of Overyssel, against the proposition. "Though not as principals, yet as auxiliaries our troops would be employed in suppressing (what some please to call) a rebellion in the American colonies; for which purpose I would rather see janisaries hired than troops from a free state. In what an odious light must this unnatural civil war appear to all Europe—a war in which even savages (if credit can be given to newspaper information) refuse to engage. More odious still would it appear for a people to take a part therein who were themselves once slaves, bore that hateful name, but at last had spirit to fight themselves free. But, above all, it must appear superlatively detestable to me, who think the Americans worthy of every man's esteem, and look upon them as a brave people, defending, in a becoming, manly, and religious manner, those rights which, as men, they derive from God, and not from the Legislature of Great Britain."

Reasons for employing German Troops.—Opposition to it in Parliament.—Terms on which the Mercenaries were hired.

021aration to enslave them. It was also intimated that the soldiers to be hired would desert as soon as they reached America; for their countrymen were numerous in the colonies, were all patriots, and would have great influence over them that they would accept land, sheathe their swords, and leave the English soldiers to do the work which their German masters sent them to perform. On the other hand, ministers counted largely upon the valor of their hirelings, many of whom were veterans, trained in the wars of Frederic the Great, and that it would be only necessary for these blood-hounds to show themselves in America to make the rebellious people lay down their arms and sue for pardon. The opposition, actuated by a sincere concern for the fair fame of their country, pleaded earnestly against the consummation of the bargain, and used every laudable endeavor to arrest the incipient action. But opposition was of little avail; North's motion for reference was carried by a majority of two hundred and forty-two to eighty-eight.

Another warm debate ensued when the committee reported on the 4th of March; 1776and in the House of Lords the Duke of Richmond moved not only to countermand the order for the mercenaries to proceed to America, but to cease hostilities altogether. The Earl of Coventry maintained that an acknowledgment of the independence of the colonies was preferable to a continuance of the war. "Look on the map of the globe," he said; "view Great Britain and North America; compare their extent, consider the soil, rivers, climate, and increasing population of the latter; nothing but the most obstinate blindness and partiality can engender a serious opinion that such a country will long continue under subjection to this. The question is not, therefore, how we shall be able to realize a vain, delusive scheme of dominion, but how we shall make it the interest of the Americans to continue faithful allies and warm friends. Surely that can never be effected by fleets and armies. Instead of meditating conquest and exhausting our strength in an ineffectual struggle, we should, wisely abandoning wild schemes of coercion, avail ourselves of the only substantial benefit we can ever expect, the profits of an extensive commerce, and the strong support of a firm and friendly alliance and compact for mutual defense and assistance." ** This was the language of wise and sagacious statesmanship—of just and honorable principles—of wholesome and vigorous thought; yet it was denounced as treasonable in its tendency, and encouraging to rebellion. The report recommending the ratification of the bargain was adopted, and the disgraceful and cruel act was consummated. The Landgrave of Hesse-Cassel agreed to furnish twelve thousand one hundred and four men; the Duke of Brunswick, four thousand and eighty-four; the Prince of Hesse, six hundred and sixty-eight, and the Prince of Waldeck, six hundred and seventy; making in all seventeen thousand five hundred and twenty-six soldiers, including the officers. Perceiving the stern necessity which compelled the British government to negotiate with them, these dealers in fighting machines drove a hard bargain with Lord George Germaine and Lord Barrington, making their price in accordance with the principle of trade, where there is a small supply for a great demand. They asked and received thirty-six dollars for each man, and in addition were to receive a considerable subsidy. The whole amount paid by the British government was seven hundred and seventy-five thousand dollars! The British king also guarantied the dominions of these princes against foreign attack. It was a capital bargain for the sellers; for, while they pocketed the enormous poll-price for their troops, they were released from the expense of their maintenance, and felt secure in their absence. Early in the spring these mercenaries, with a considerable number of troops from England and Ireland, sailed for America, under convoy of a British fleet commanded by Admiral Lord Howe. ***The fierce German

* It was estimated that, when the Revolution broke out, there were about one hundred and fifty thousand German emigrants in the American colonies, most of whom had taken sides with the patriots.

** Cavendish's Debates.

*** Admiral Howe, who was a man of fine feelings, hesitated long before he would accept the command of the fleet destined to sail against his fellow-subjects in America. In Parliament, a few days before he sailed, he spoke with much warmth upon the horrors of civil war, and "declared that he knew no struggle so painful as that between a soldier's duties as an officer and a man. If left to his own choice, he should decline serving; but if commanded, it beeame his duty, and he should not refuse to obey." General Conway said a war with our fellow-subjects in America differed very widely from a war with foreign nations, and that before an officer drew his sword against his fellow-subjects he ought to examine well his conscience whether the cause were just. Thurlow declared that such sentiments, if once established as a doctrine, must tend to a dissolution of all governments.—Pictorial History of England, v., 248.

Parliament alarmed by a Rumor.—French Emissary in Philadelphia.—Official Announcement of the Evacuation of Boston.

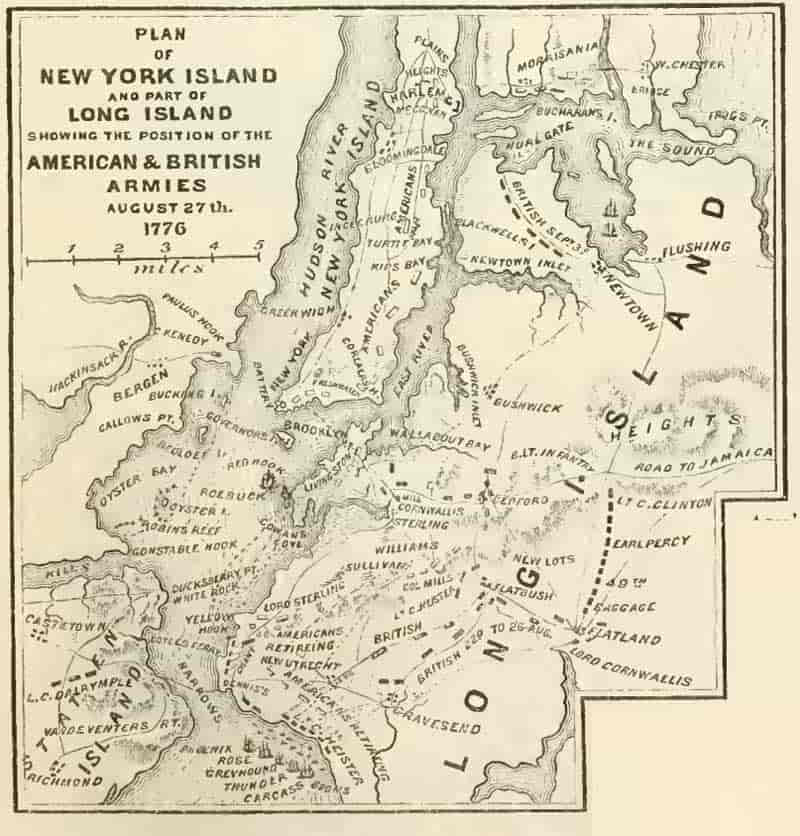

022warriors—fierce, because brutish, unlettered, and trained to bloodshed by the continental butchers—were first let loose upon the patriots in the battle of Long Island, * and thenceforth the Hessians bore a prominent part in many of the conflicts that ensued.

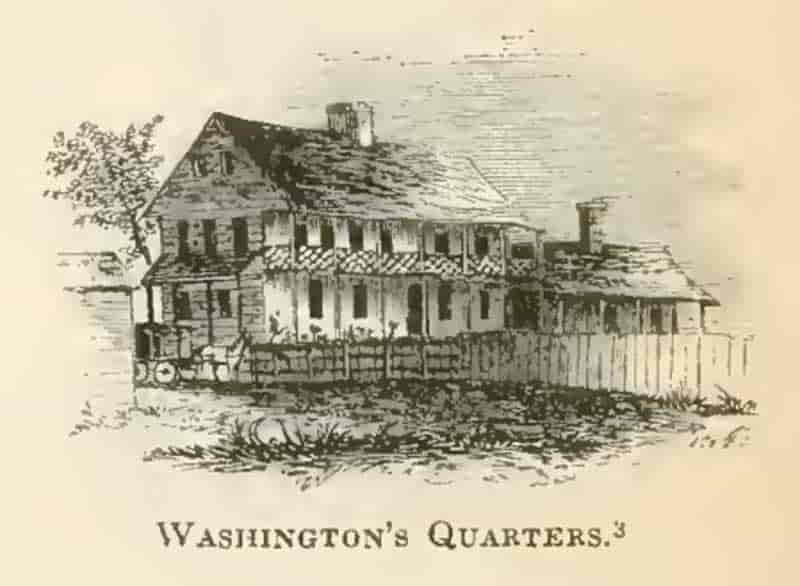

During the residue of the session of Parliament under consideration, American affairs occupied a good portion of the time of the Legislature, but nothing of great importance was done. The Duke of Grafton made an unsuccessful attempt to have an address to the king adopted, requesting that a proclamation might be issued to declare that if the colonists should, within a reasonable time, show a willingness to treat with the commissioners, or present a petition, hostilities should be suspended, and their petition be received and respected. He assured the House that both France and Spain were arming; and alarmed them by the assertion that "two French gentlemen had been to America, had conferred with Washington at his camp, and had since been to Philadelphia to confer with Congress. ** The duke's proposition was negatived.

A very brief official announcement of the evacuation of Boston appeared in the London Gazette of the 3d of May, 1776. *** Ministers endeavored to conceal full intelligence of the transaction, and assumed a careless air, as if the occurrence were of no moment. But Colonel Barré would not allow them to rest quietly under the cloak of mystery, but moved in the House of Commons for an address to his majesty, praying that copies of the dispatches of General Howe and Admiral Shuldham might be laid before the House. There, and in the House of Lords, the ministry were severely handled. Lord North declared that the army was not compelled to abandon Boston, when he well knew to the contrary; and Lord George Germaine's explanation was weak and unsatisfactory. The thunders of Burke's eloquent denunciations were opened against the government, and he declared that "every measure which had been adopted or pursued was directed to impoverish England and to emancipate America; and though in twelve months nearly one thousand dollars a man had been

* I intended to defer a notice of these German troops (generally called Hessians, because the greater portion came from Hesse and Hesse-Cassel) until the battle of Long Island should be under consideration; but the action relative to their employment occupies such a conspicuous place in the proceedings of the session of Parliament, where the most decided hostile measures against America were adopted, that here seemed the most appropriate place to notice the subject in detail. See note 2, page 164, vol. ii.

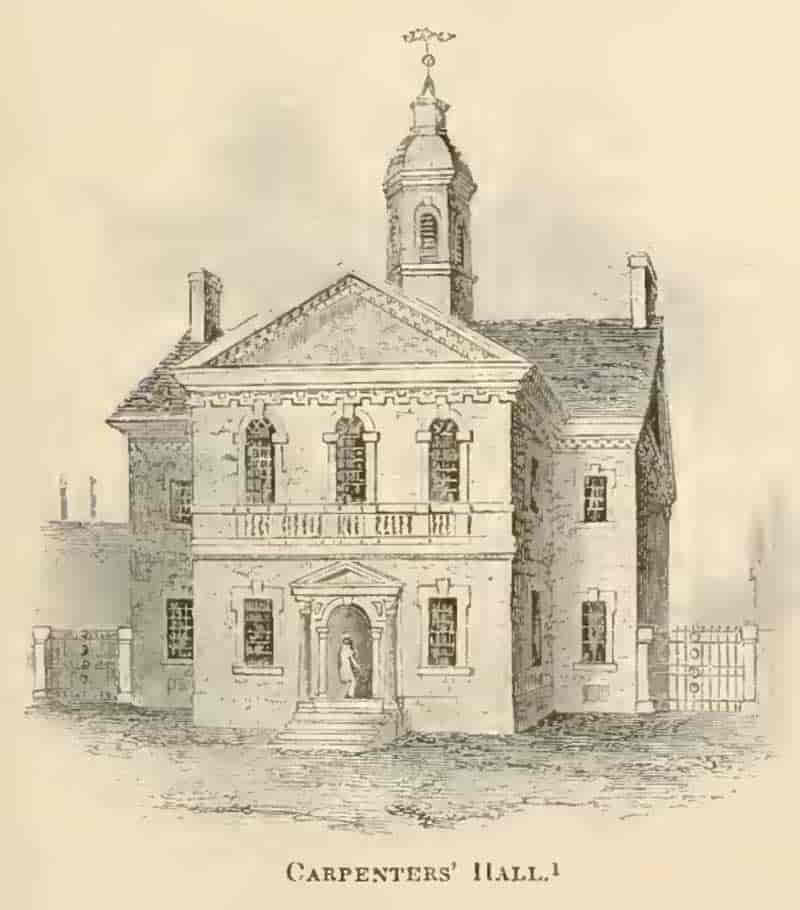

** Some time in the month of November, 1775, Congress was informed that a foreigner was in Philadelphia who was desirous of making to them a confidential communication. At first no notice was taken of it, but the intimation having been several times repeated, a committee, consisting of John Jay, Dr. Franklin, and Thomas Jefferson, was appointed to hear what he had to say. They agreed to meet him in a room in Carpenters' Hall, and, at the time appointed, they found him there—an elderly, lame gentleman, and apparently a wounded French officer. He told them that the French king was greatly pleased with the exertions for liberty which the Americans were making; that he wished them success, and would, whenever it should be necessary, manifest more openly his friendly sentiments toward them. The committee requested to know his authority for giving these assurances. He answered only by drawing his hand across his throat, and saving, "Gentlemen, I shall take care of my head." They then asked what demonstrations of friendship they might expect from the King of France. "Gentlemen," he answered, "if you want arms, you shall have them: if you want ammunition, you shall have it; if you want money, you shall have it." The committee observed that these were important, assurances, and again desired to know by what authority they were made. "Gentlemen," said he, again drawing his hand across his throat, "I shall take care of my head;" and this was the only answer they could obtain from him. He was seen in Philadelphia no more.—See Life of John Jay, written by his son, William Jay.

*** The official announcement in the Gazette was as follows: "General Howe, commander-in-chief of his majesty's forces in North America, having taken a resolution on the 7th of March to remove from Boston to Halifax with the troops under his command, and such of the inhabitants, with their effects, as were desirous to continue under the protection of his majesty's forces; the embarkation was effected on the 17th of the same month, with the greatest order and regularity, and without the least interruption from the rebels When the packet came away, the first division of transports was under sail, and the remainder were preparing to follow in a few days, the admiral leaving behind as many men-of-war as could be spared from the convoy for the security and protection of such vessels as might be bound to Boston."

Royal Approval of Howe's Course.—Opinions of the People.—Position of the Colonies.—Count Rumford. Fortifications.

023spent for salt beef and sour-krout, * the troops could not have remained ten days longer if the heavens had not rained down manna and quails."

The majority voted down every proposition to elicit full information respecting operations in America, and on the 23d of May his majesty, after expressing a hope "that his rebellious subjects would yet submit," prorogued Parliament.

The evacuation of Boston was approved by the king and his ministers, and on the day when the announcement of the event was made in London, Lord George Germaine May 3, 1776 wrote to Howe, deploring the miscarriage of the general's dispatches for the ministers, **

praising his prudence, and assuring him that his conduct had "given the fullest proofs of his majesty's wisdom and discernment in the choice of so able and brave an officer to command his troops in America."

Thus ended the Siege of Boston, where the first decided triumph of American arms over the finest troops of Great Britain was accomplished. The departure of Howe was regarded in England as a flight; the patriots viewed it as a victory for themselves. Confidence in their strength to resist oppression was increased ten-fold by this event, and doubt of final and absolute success was a stranger to their thoughts. "When the siege of Boston commenced, the colonies were hesitating on the great measures of war; were separated by local interests; were jealous of each other's plans, and appeared on the field, each with its independent army under its local colors. When the siege of Boston ended, the colonies had drawn the sword and nearly cast away the scabbard. They had softened their jealousy of each other; they had united in a political association; and the Union flag of thirteen stripes waved over a Continental army." ***

Few events of more importance than those at other large sea-port towns occurred at Boston after the flight of the British army. The Americans took good care to keep their fortifications in order, and a full complement of men to garrison them sufficiently. **** This fact

* A Dutch or German dish, made of cabbage.

*** It appears that Howe sent dispatches to England on the 23d of October, 1775. by the hands of Major Thompson, and those were the last from him that reached the ministry before the army left Boston for Halifax. Major Thompson was afterward the celebrated philosopher. Count Rumford. He was a native of Woburn, in Massachusetts, and was born on the 26th of March, 1753. He early evinced a taste for philosophy and the mechanic arts, and obtained permission to attend the philosophical lectures of Professor Winthrop at Cambridge. He afterward taught school at Rumford (now Concord), New Hampshire, where he married a wealthy young widow. In consequence of his adhesion to the British cause, he left his family in the autumn of 1775, went to England, and became a favorite of Lord George Germaine, who made him under secretary in the Northern Department. Near the close of the Revolution he was sent to New York, where he commanded a regiment of dragoons, and returning to England, the king knighted him. He became acquainted with the minister of the Duke of Bavaria, who induced him to go to Munich, where he became active in public affairs. The duke raised him to a high military rank, and made him a count of the empire. He added to his title the place of his marriage, and became Count Rumford. He was in London in 1800, and projected the Royal Institution of Great Britain. His wife, whom he abandoned, died in 1794 in New Hampshire. Count Rumford died August 20th, 1814, aged sixty-one vears. His scientific discoveries have made his name immortal. He bequeathed fifty thousand dollars to Harvard College.

*** Frothingham, page 334.

**** With the exception of Dorchester, Bunker Hill, and Roxbury, I believe there are few traces of the fortifications of the Revolution that can be certainly identified; and so much altered has been the fortress on Castle Island that it exhibits but little of the features of 1776. Every year the difficulty of properly locating the several forts becomes greater, and therefore to preserve, in this work, a record of those landmarks by which they may be identified, I condense from Silliman's Journal for 1822 an interesting article on the subject which was communicated by J. Finch, Esq., with such references as later writers have made. A recurrence to the map on page 566, vol. i., will assist the reader.

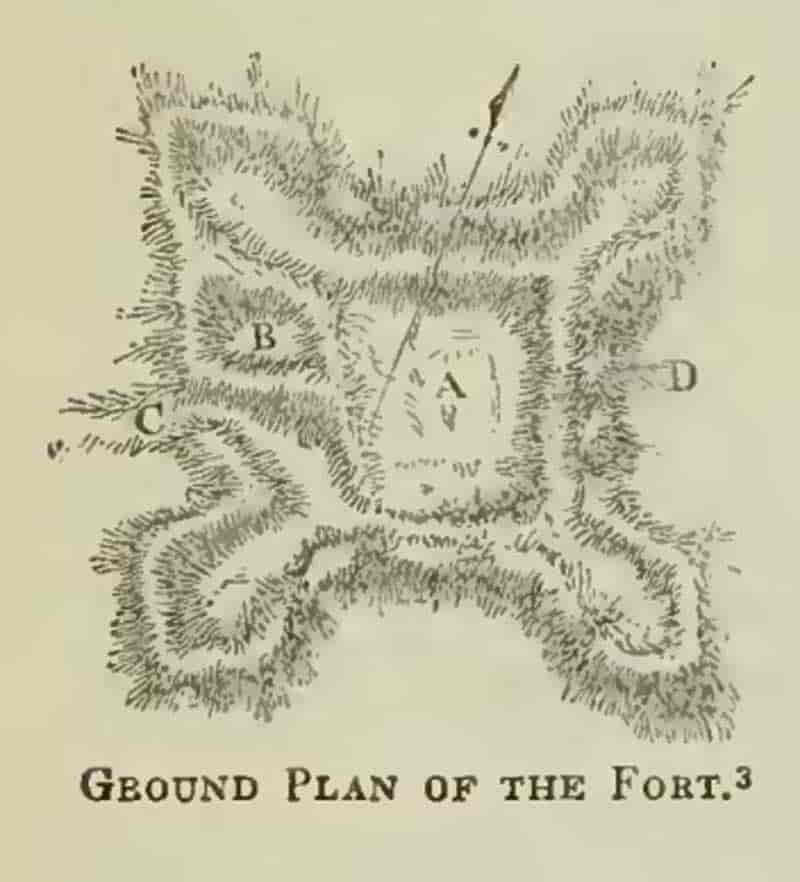

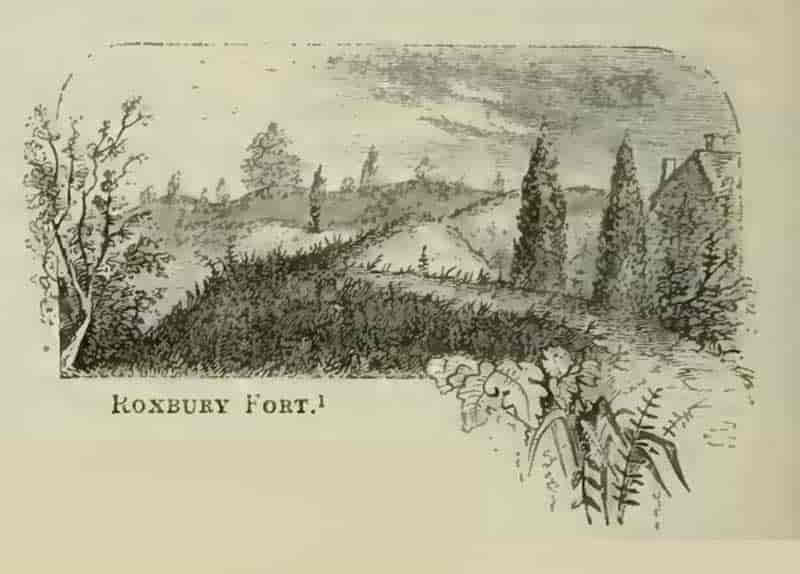

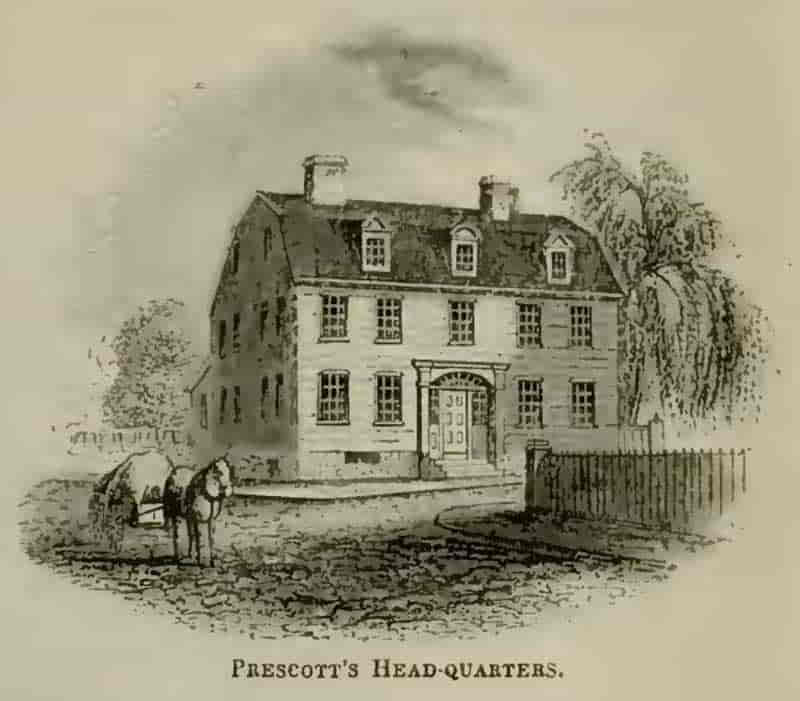

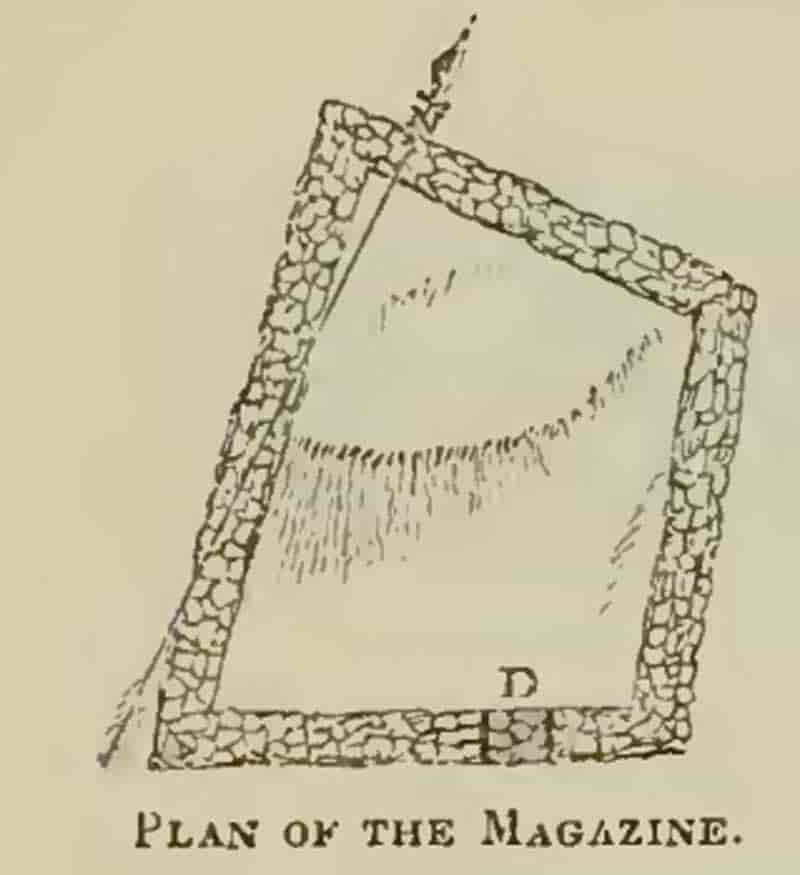

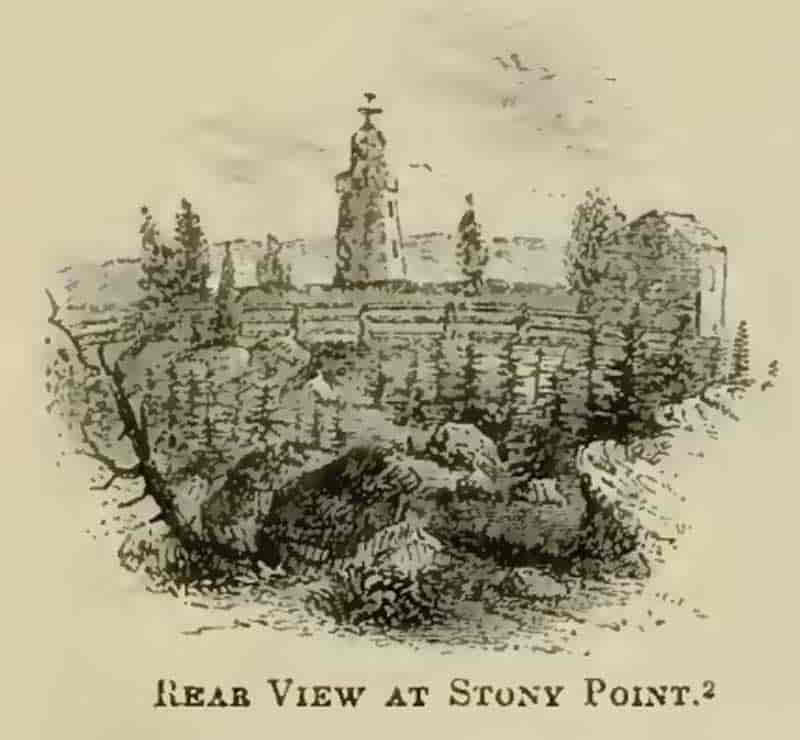

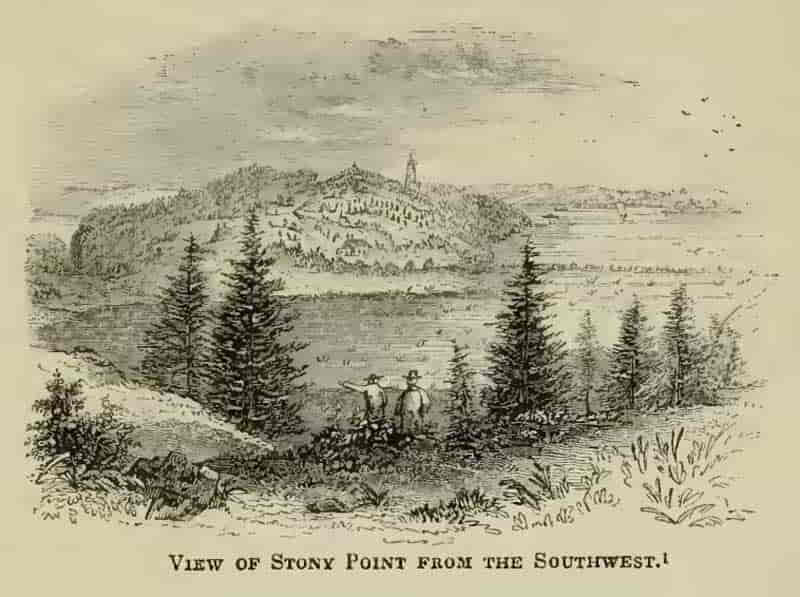

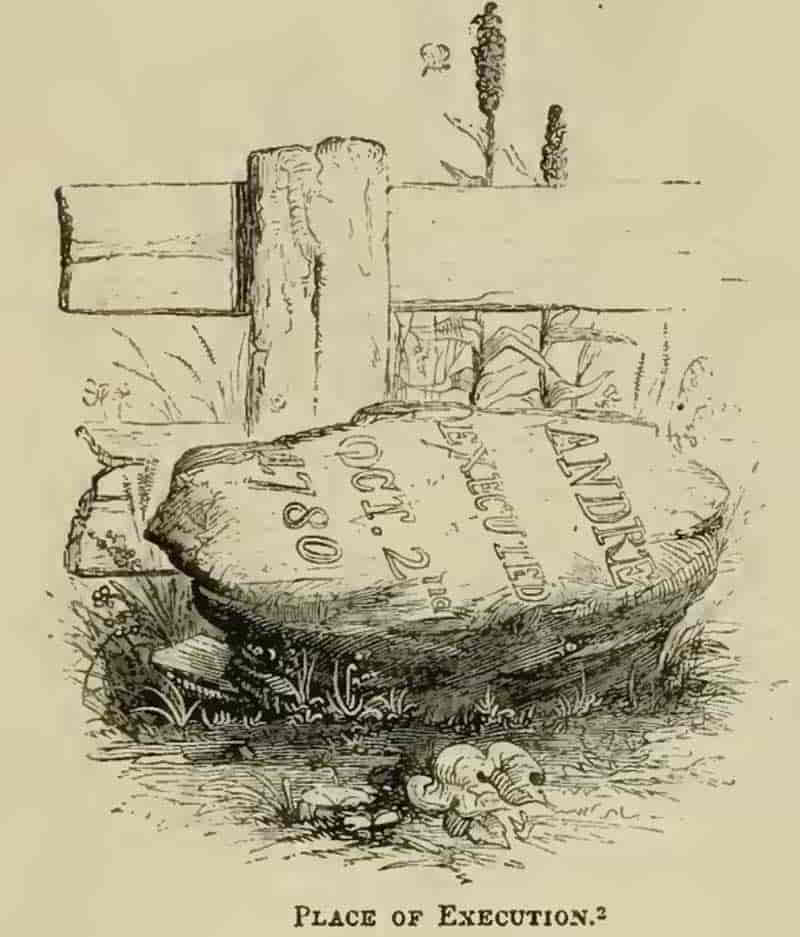

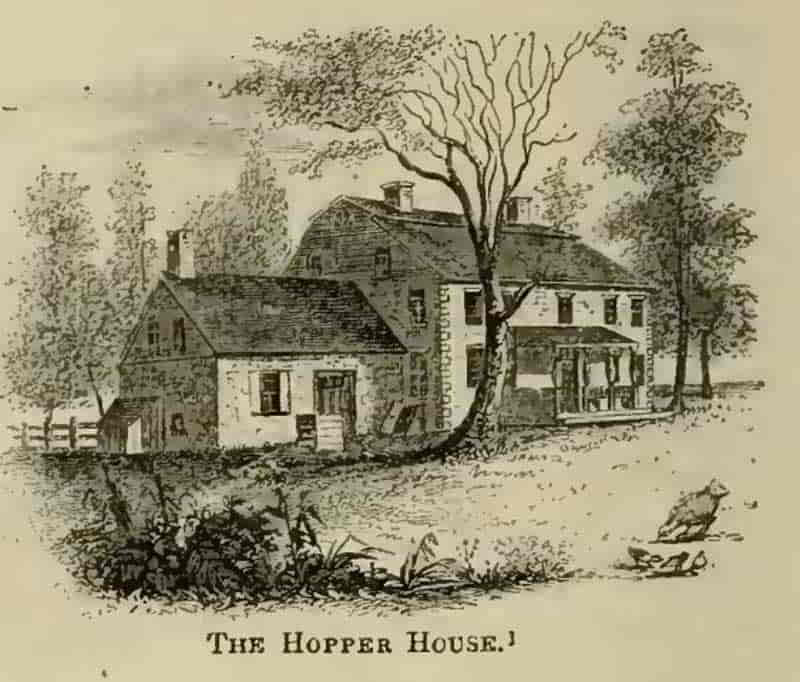

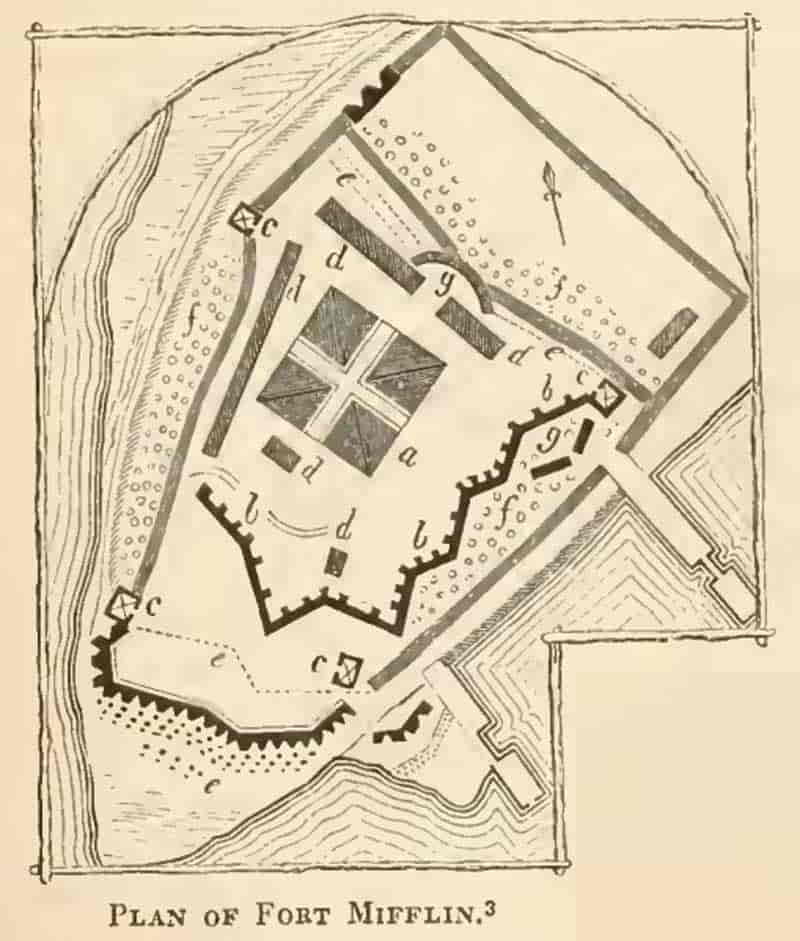

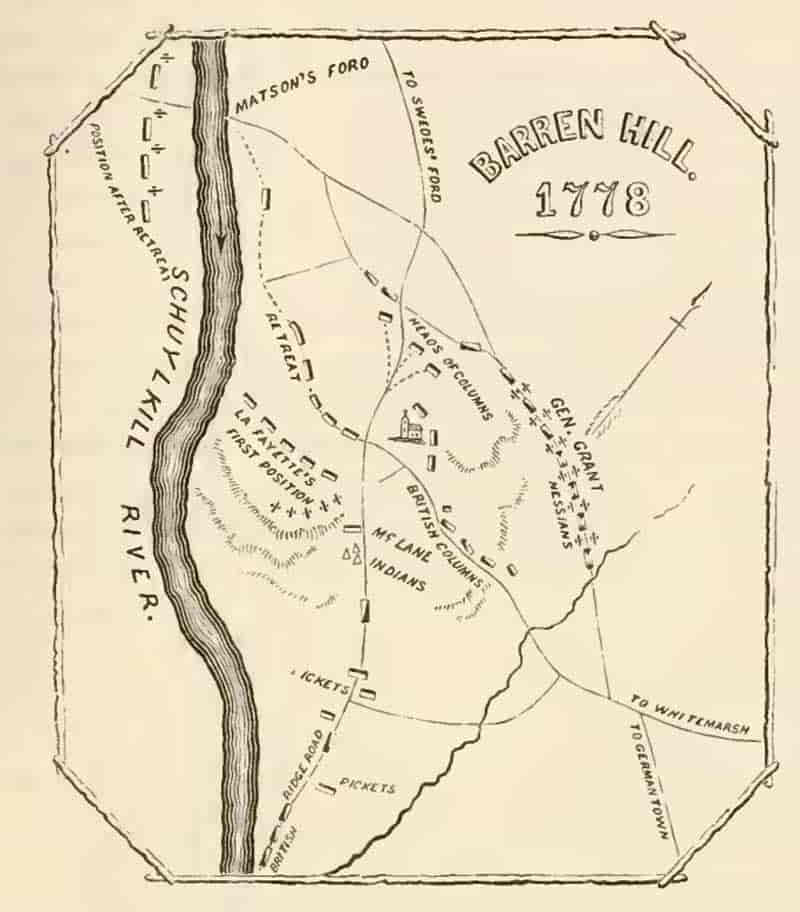

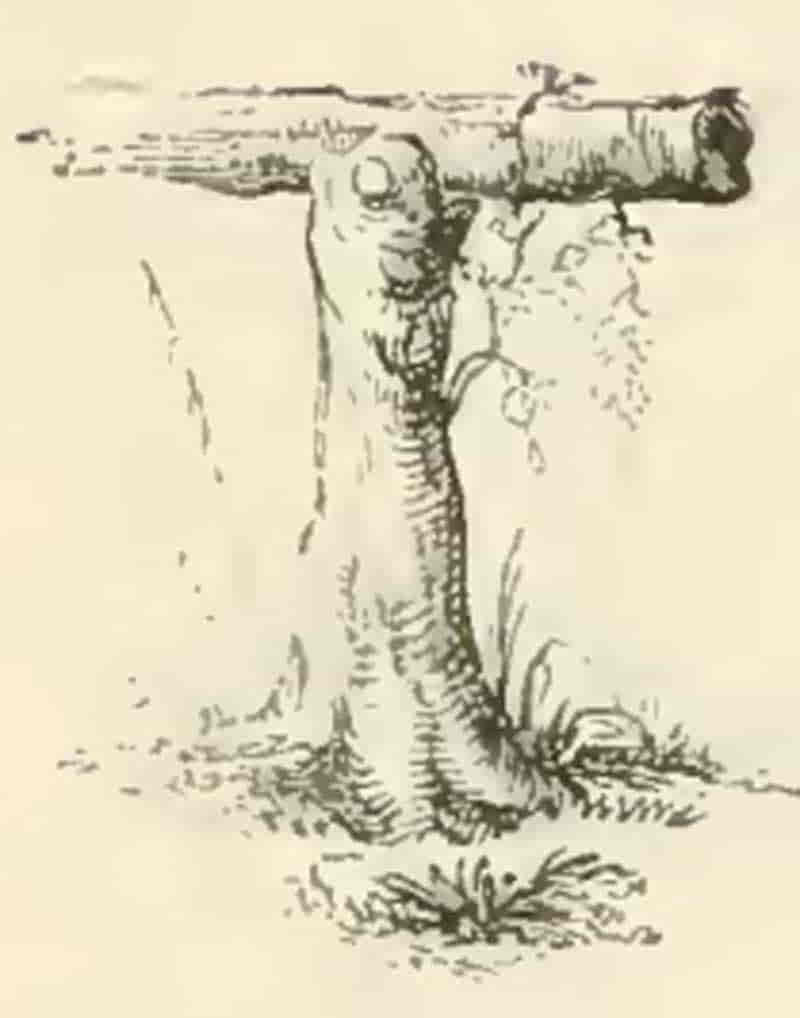

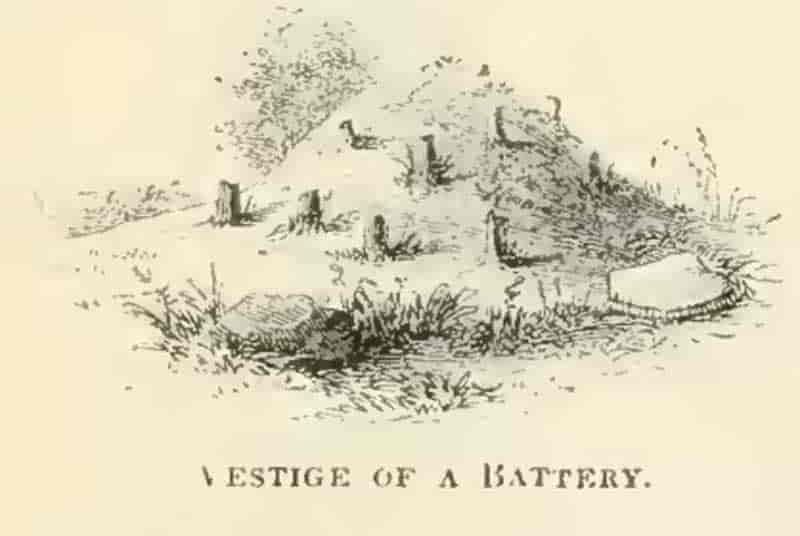

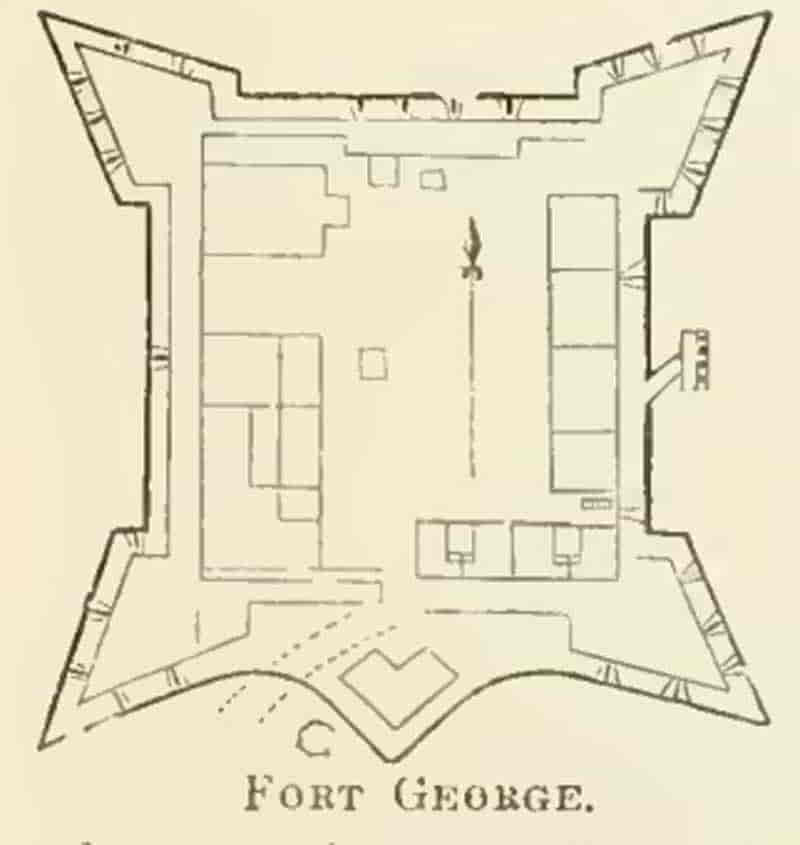

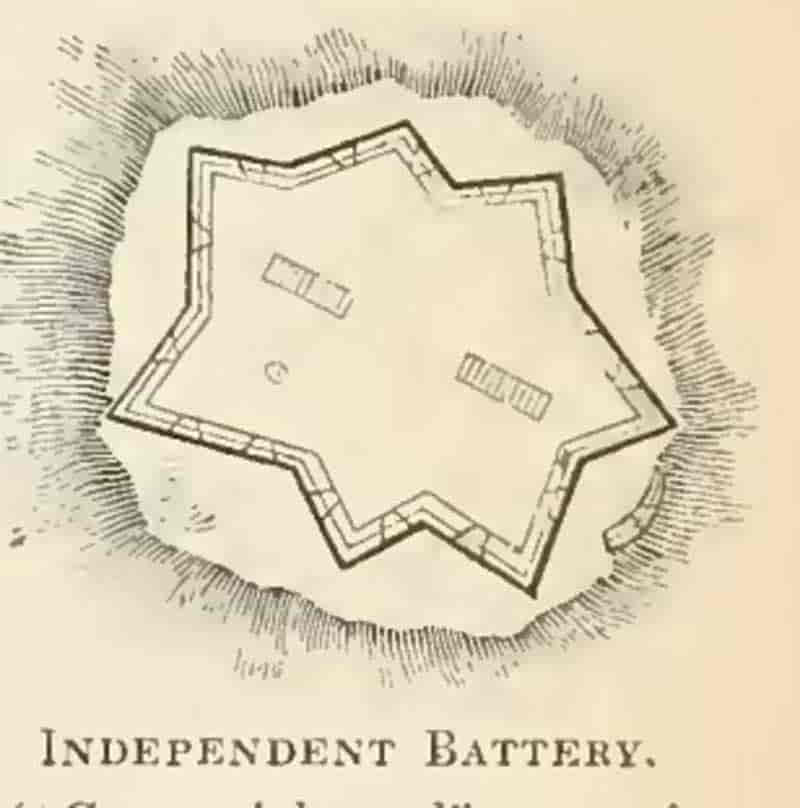

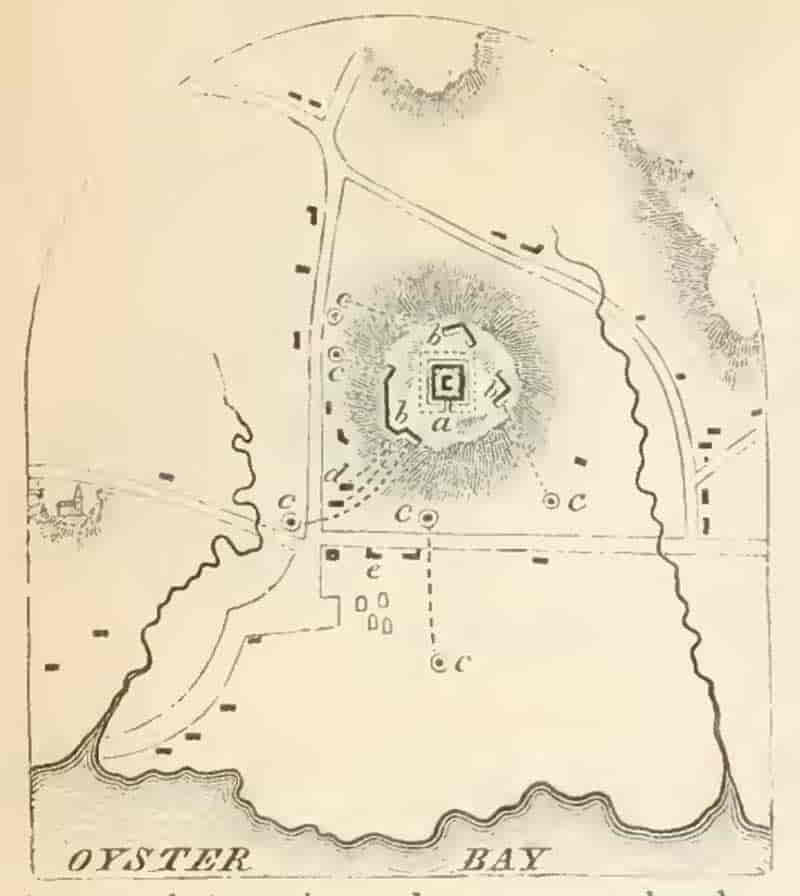

**** I. Breed's Hill and Bunker Hill.—These works were on the summits and slopes of the hills, looking toward Boston. Bunker Hill Monument now stands upon the spot where Prescott's redoubt was thrown up. II. Plowed Hill.—This fort was upon the summit of the eminence, commanding the Mystic River and the Penny Ferry. It was in a direct line from Charlestown Neck to Winter Hill, further northward. III. Cobble or Barrell's Hill.—In consequence of its strength, the fort on this hill was called Putnam's impregnable fortress. This was on the north side of Willis's Creek, in full view of Bunker and Breed's Hills, and commanding the whole western portion of the peninsula of Charlestown. IV. Lechmere's Point was strongly fortified at a spot one hundred yards from West Boston Bridge There was a causeway across the marsh, and a line of works along Willis's Creek to connect with those on Cobble Hill. V. Winter Hill.—The works at this point, commanding the Mystic and the country northward from Charlestown, were more extensive than any other American fortification around Boston. There rested the left wing of the army under General Lee, at the time of the siege of Boston. There was a redoubt near, upon the Ten Hill Farm, that commanded the Mystic; and between Winter and Prospect Hills was a re-doubt, where a quarry was opened about the year 1819. This was called White House Redoubt, in the rear of which, at a farm-house, Lee had his quarters. VI. Prospect Hill has two eminences, both of which were strongly fortified, and connected by a rampart and fosse, or ditch. These forts were destroyed in 1817. There is an extensive view from this hill. VII. The Cambridge Lines, situated upon Butler's Hill, consisted of six regular forts connected by a strong intrenchment. These were in a state of excellent preservation when Mr. Finch wrote. The Second Line of Defense might then be traced on the College Green at Cambridge. VIII. A semicircular Battery, with three embrasures, was situated on the northern shore of Charles River, near its entrance into the bay. It was rather above the level of the marsh. IX. Brookline Fort, on Sewall's Point, was very extensive. The ramparts and irregular bastion, which commanded Charles River, were very strong. The fort was nearly quadrangular. X. There was a battery on the southern shore of Muddy River, with three embrasures. Westward of this position was a redoubt; and between Stony Brook and Roxbury were three others. XI. Roxbury.—There were strong fortifications at this point, erected upon eminences which commanded Boston Neck, sometimes called Roxbury Neck. About three quarters of a mile in advance of these redoubts were The Roxbury Lines, situated northward of the town. There were two lines of intrenchments, which extended quite across the peninsula; and the ditch, filled at high water, made Boston an island. The works thrown up by Gage when he fortified Boston Neck were near the present Dover Street. Upon a higher eminence, in the rear of the Roxbury lines (at present [[1850]] west of Highland Street, on land owned by the Honorable B. F. Copeland), was Roxbury Fort,1 2 a strong quadrangular work, with bastions appears to have been on the southwest side, near which was a covered way and sally-port. I have nowhere seen a fortification of the Revolution so well preserved as this, except the old quadrangular fort or castle at Chambly, on Ground Plan of the Fort.3 the Sorel; and it is to be hoped that patriotic reverence will so consecrate the ground on which this relic lies, that unhallowed gain may never lay upon the old ramparts the hand of demolition. The history of the construction of Roxbury Fort is somewhat obscure. It is known to have been the first regular work erected by the Americans when they nearly circumvallated Boston. Tradition avers, that when the Rhode Island "Army of Observation," which hastened toward Boston, under Greene, after the skirmishes at Lexington and Concord, encamped at Jamaica Plains, a detachment was sent forward and commenced this redoubt at Roxbury. General Ward, who, by common consent, was captain-general of the accumulating forces, ordered them to desist, as he was about to commence a regular line of fortifications under the direction of Gridley. The Rhode Islanders, acknowledging no authority but their own Provincial Assembly, proceeded in their work; and when Washington took command of the army, he regarded this fort as the best and most eligibly located of all the works then in course of construction. During the siege of Boston, Roxbury Fort was considered superior to all others for its strength and its power to annoy the enemy. XII. Dorchester Heights.—The ancient fortifications there are covered by the remains of those erected in 1812, and have little interest except as showing the locality of the forts of the Revolution. XIII. At Nook's Hill, near South Boston Bridge, the last breast-work was thrown up by the American^ before the flight of the British. It was the menacing appearance of this suddenly-erected fort that caused Howe to hasten his departure. The engineers employed in the construction of these works were Colonel Richard Gridley, chief; Lieutenant-colonel Rufus Putnam, Captain Josiah Waters, Captain Baldwin, o! Brookfield, and Captain Henry (afterward general) Knox, assistants. These were the principal works erected and occupied by the Americans at Boston. When Mr. Finch wrote in 1822, many of these were well preserved, and he expressed a patriotic desire that they should remain so. But they are gone, and art has covered up the relics that were left. But it is not yet too late to carry out a portion of his recommendation, by which to preserve the identity of some of the localities. "The laurel, planted on the spot where Warren fell, would be an emblem of unfading honor; the white birch and pine might adorn Prospect Hill: at Roxbury, the cedar and the oak might yet retain their eminence; and upon the heights of Dorchester we would plant the laurel, and the finest trees which adorn the forest, because there was achieved a glorious victory, without the sacrifice of life!"

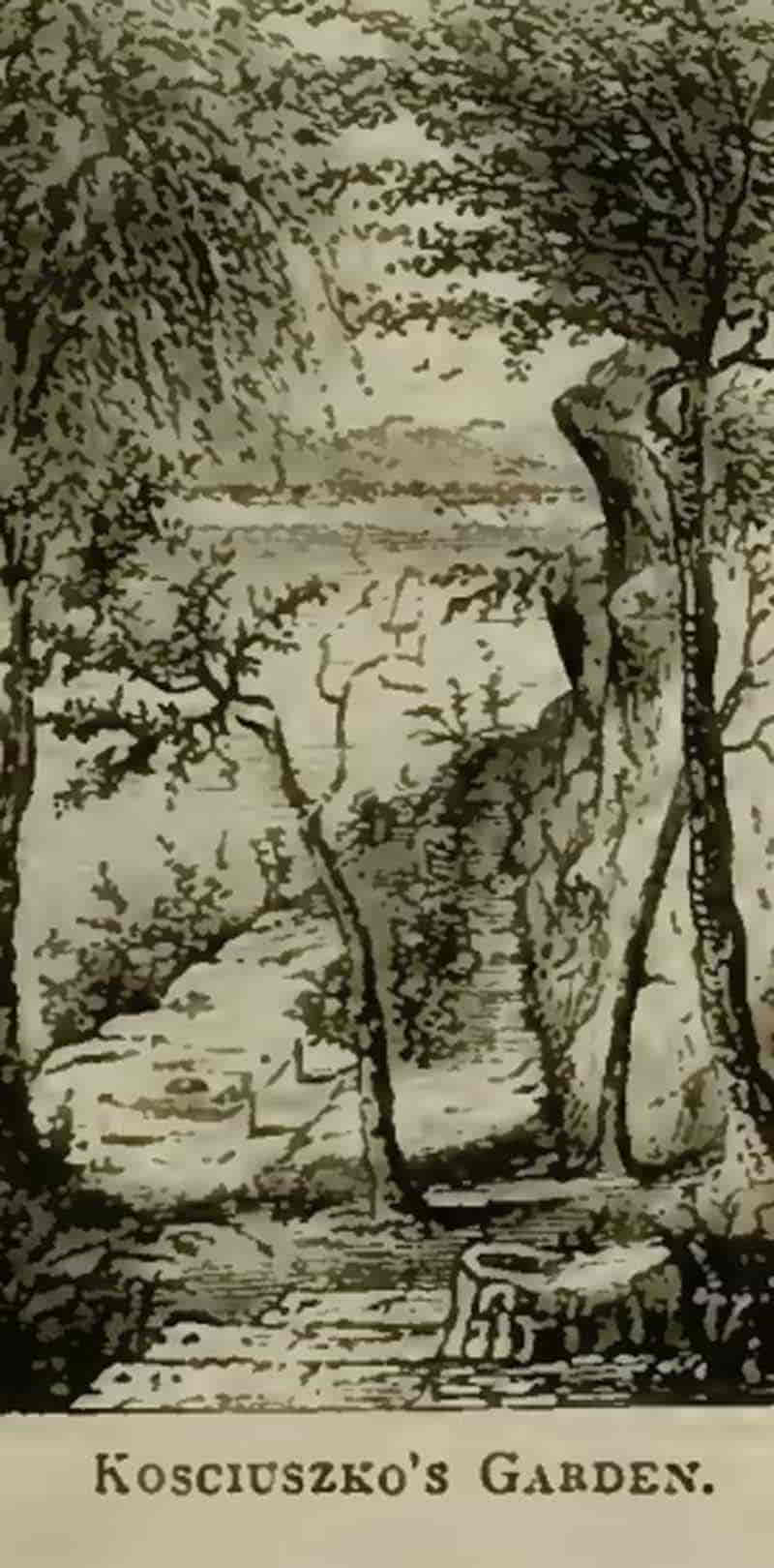

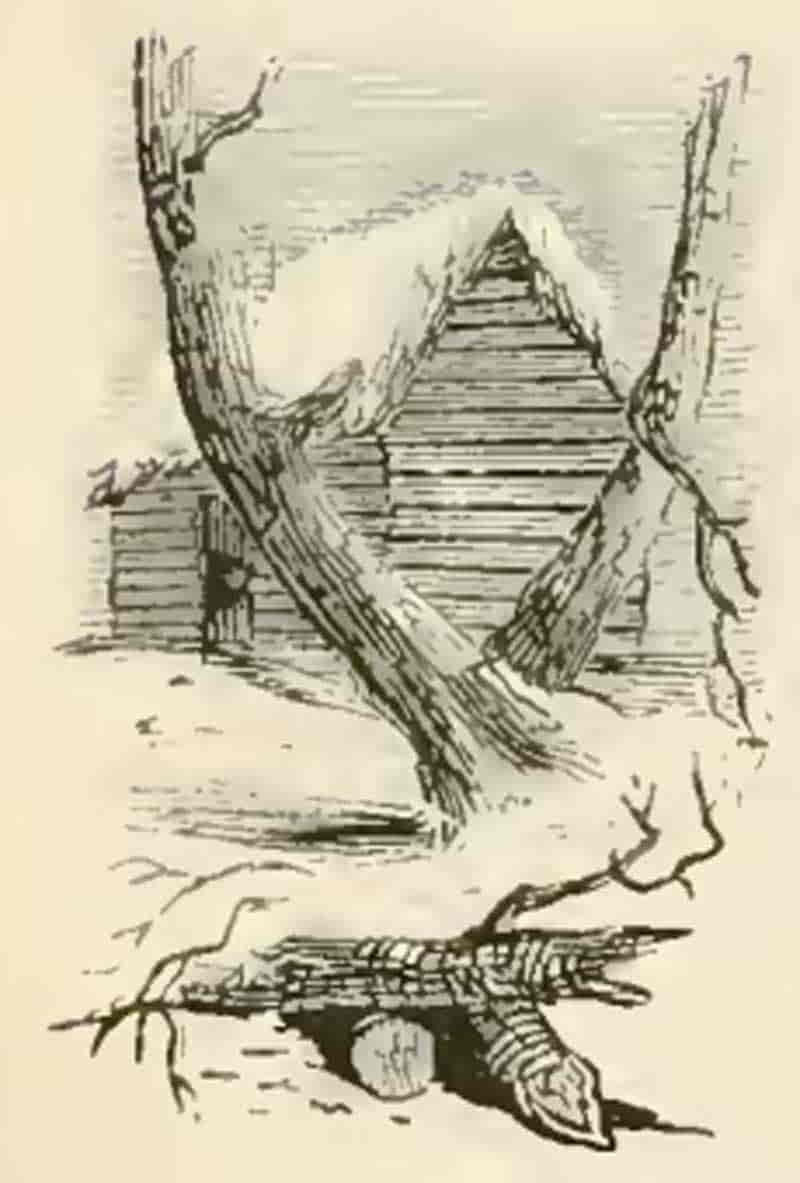

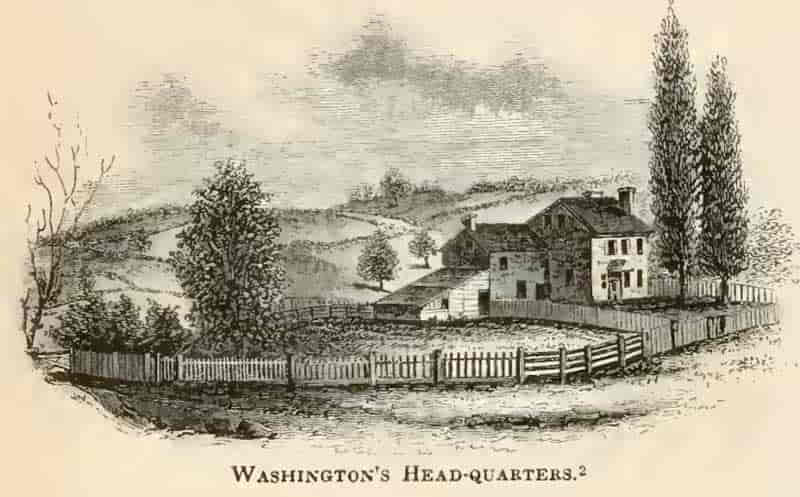

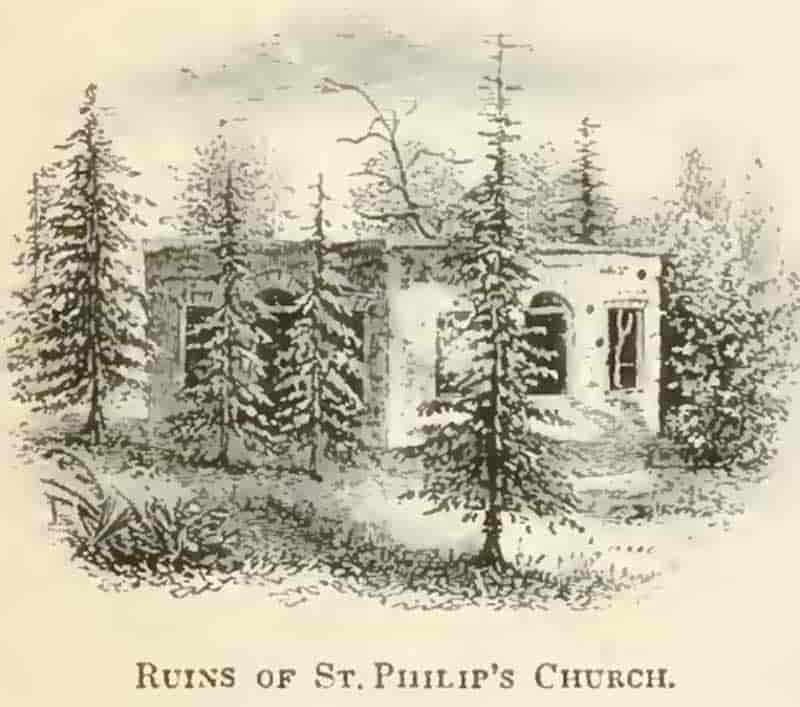

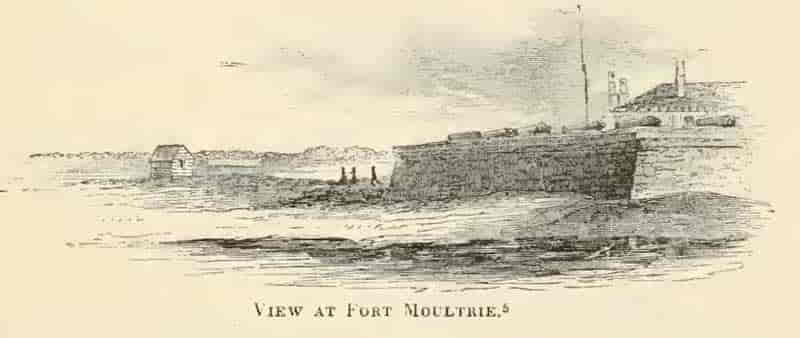

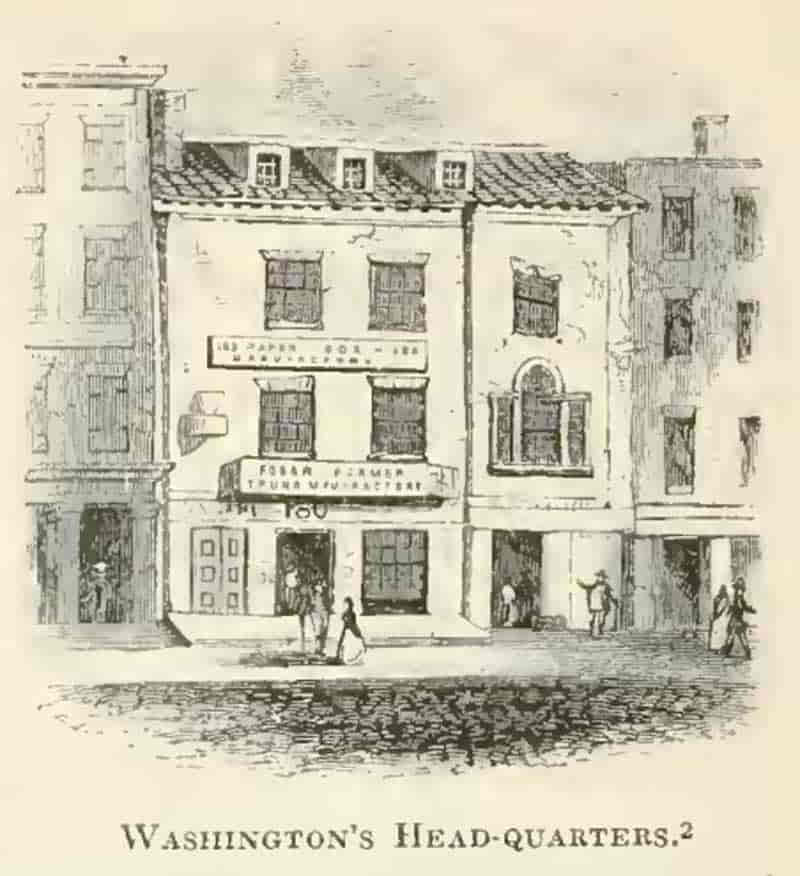

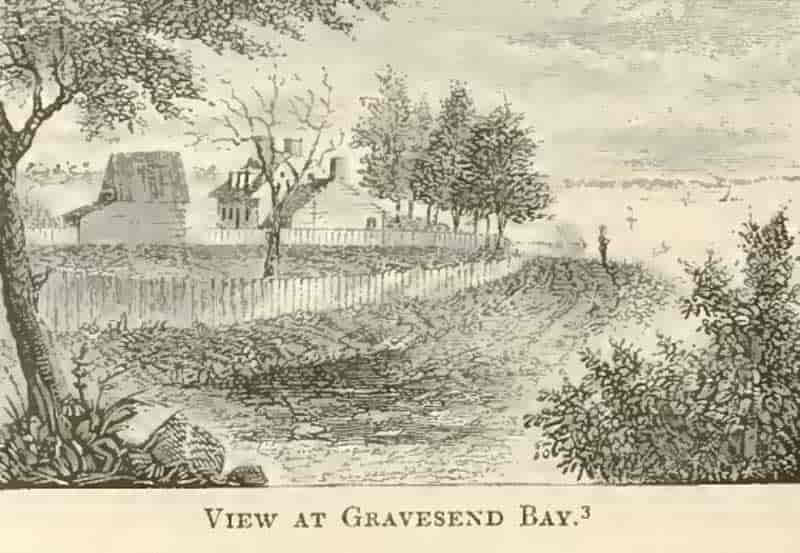

* This view is from the southwest angle of the fort. In the foreground a portion of the ramparts is seen. These are now overgrown, in part, with shrubbery. On the right is seen the house of Mr. Benjamin Perkins, on Highland Street, and extending across the picture, to the left, is the side of the fort toward Boston, exhibiting prominent traces of the embrasures for the cannons. It was a foggy day in autumn when I visited the fort, in company with Frederic Kidder, Esq., of Boston, to whose courtesy and antiquarian taste I am indebted for the knowledge of the existence of this well-preserved fortification. No distant view could be procured, and I was obliged to be content with the above sketch, made in the intervals of "sun and shower." The bald rocks on which the fort stands are huge bowlders of pudding-stone, and upon three sides these form natural revetments, which would be difficult for an enemy to scale. The embankments are from eight to fifteen feet in height, and within, the terre-plein, on which the soldiers and cannons were placed, is quite perfect.

** See map on page 566, vol. i.

*** This is a ground plan of the fort as it now appears. A is the parade; B, the magazine; C, the sally-port D, the side toward Boston.

Boston Harbor.—Remains of the Revolutionary Fortifications around Boston

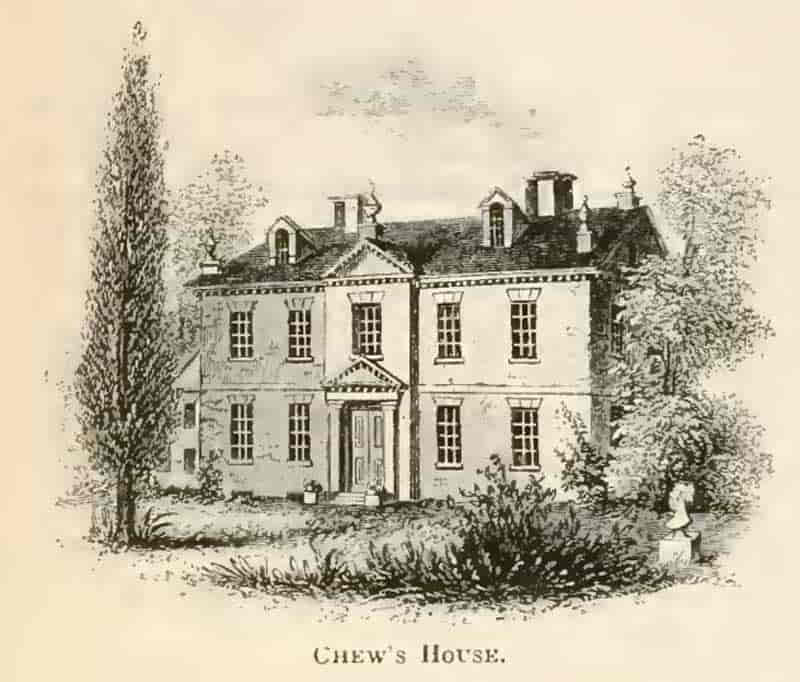

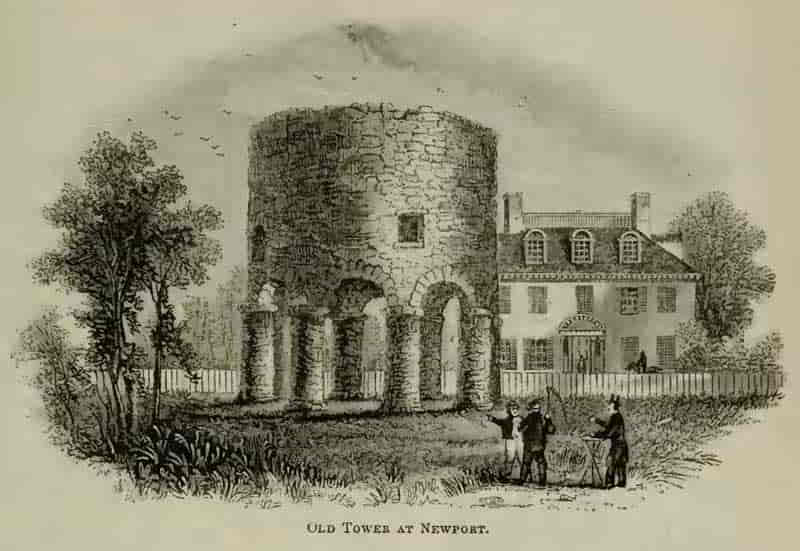

024seemed to be well known to the enemy; for while Newport and the places adjacent suffered from the naval operations of British vessels, Boston Harbor was shunned by them. Some

The "Convention Troops."—Their Parole of Honor.—Picture of the Captives.—Burgoyne in Boston