.

ARCHAIC ENGLAND

AN ESSAY IN DECIPHERING PREHISTORY FROM

MEGALITHIC MONUMENTS, EARTHWORKS,

CUSTOMS, COINS, PLACE-NAMES, AND

FAERIE SUPERSTITIONS

BY

HAROLD BAYLEY

AUTHOR OF “THE SHAKESPEARE SYMPHONY,” “A NEW LIGHT ON THE RENAISSANCE,”

“THE LOST LANGUAGE OF SYMBOLISM,” ETC.

“One by one tiny fragments of testimony accumulate attesting such a survival and continuance of folk memory as few men of to-day have suspected.”—Johnson

LONDON

CHAPMAN & HALL LTD.

11 HENRIETTA STREET

1919

TO

W. L. GROVES

WHO HAS GREATLY AIDED ME

CONTENTS

| CHAP | PAGE | |

| I. | Introductory | 1 |

| II. | The Magic of Words | 34 |

| III. | A Tale of Troy | 78 |

| IV. | Albion | 124 |

| V. | Gog and Magog | 186 |

| VI. | Puck | 230 |

| VII. | Oberon | 309 |

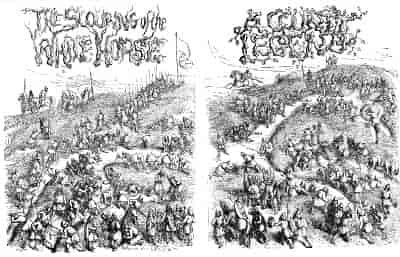

| VIII. | Scouring the White Horse | 389 |

| IX. | Bride’s Bairns | 455 |

| X. | Happy England | 522 |

| XI. | The Fair Maid | 593 |

| XII. | Peter’s Orchards | 663 |

| XIII. | English Edens | 710 |

| XIV. | Down Under | 764 |

| XV. | Conclusions | 832 |

| Appendix | 871 | |

| Appendix A: Ireland and Phœnicia. | 871 | |

| Appendix B: Perry-Dancers and Perry Stones. | 873 | |

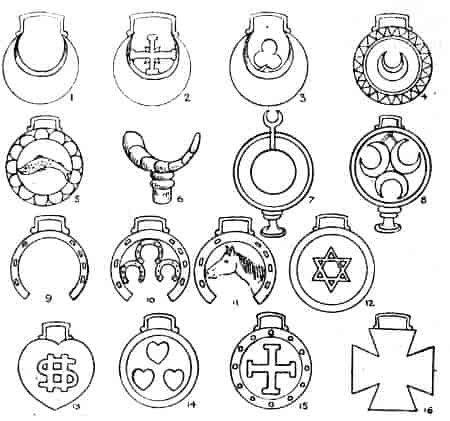

| Appendix C: British Symbols. | 874 | |

| Appendix D: Glastonbury. | 875 | |

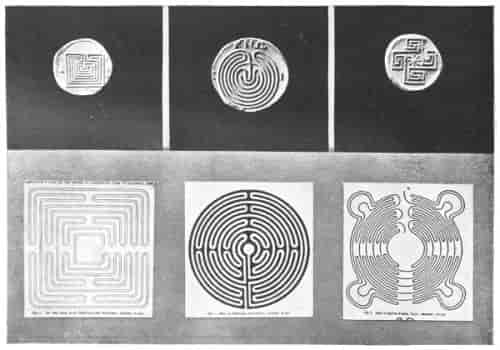

| Appendix E: The Druids and Crete. | 875 | |

| Index | 877 |

“Of all the many thousands of earthworks of various kinds to be found in England, those about which anything is known are very few, those of which there remains nothing more to be known scarcely exist. Each individual example is in itself a new problem in history, chronology, ethnology, and anthropology; within every one lie the hidden possibilities of a revolution in knowledge. We are proud of a history of nearly twenty centuries: we have the materials for a history which goes back beyond that time to centuries as yet undated. The testimony of records carries the tale back to a certain point: beyond that point is only the testimony of archæology, and of all the manifold branches of archæology none is so practicable, so promising, yet so little explored, as that which is concerned with earthworks. Within them lie hidden all the secrets of time before history begins, and by their means only can that history be put into writing: they are the back numbers of the island’s story, as yet unread, much less indexed.”—A. Hadrian Allcroft.

“It is a gain to science that it has at last been recognised that we cannot penetrate far back into man’s history without appealing to more than one element in that history. Some day it will be recognised that we must appeal to all elements in that history.”—Gomme.

“History bears and requires Authors of all sorts.”—Camden.

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

“If a man does not keep pace with his companions, perhaps it is because he hears a different drummer. Let him step to the music which he hears, however measured or far away.”—H. D. Thoreau.

This book is an application of the jigsaw system to certain archæological problems which under the ordinary detached methods of the Specialist have proved insoluble. My fragments of evidence are drawn as occasion warrants from History, Fairy-tale, Philosophy, Legend, Folklore—in fact from any quarter whence the required piece unmistakably fulfils the missing space. It is thus a mental medley with all the defects, and some, I trust, of the attractions, of a mosaic.

Ten years ago I published a study on Mediæval Symbolism, and subsequent investigation of cognate subjects has since put me in possession of some curious and uncommon information, which lies off the mainroads of conventional Thought.

The consensus of opinion upon A New Light on the Renaissance,[1] was to the effect that my theories were decidedly ingenious and up to a point tenable, yet nevertheless at present they could only be regarded as non-proven. In 1912[2] I therefore endeavoured to substantiate my earlier propositions, pushing them much further to the point of suggesting an innate connection between Symbolism and certain words—such, for example, as psyche, which means a butterfly, and psyche the anima or soul which was symbolised or represented by a butterfly. Of course I knew only too well the tricky character of the ground I was exploring and how open many of my propositions would be to attack, yet it seemed preferable rather to risk the Finger of Scorn than by a superfluity of caution ignore clues, which under more competent hands might yield some very interesting and perhaps valuable discoveries.

In the present volume I piece together a mosaic of visible and tangible evidence which is supplementary to that already brought forward, and the results—at any rate in many instances—cannot by any possibility be written off as due merely to coincidence or chance. That they will be adequate to satisfy the exacting requirements of modern criticism is, however, not to be supposed. Referring to The Lost Language, one of my reviewers cheerfully but disconcertingly observed: “He must deal as others of his school have done with all the possible readings of the history of the races of men”.[3] To sweeping and magnanimous advice of this character one can only counter the untoward experiences of the hapless “Charles Templeton,” as recounted by Mr. Stephen McKenna: “At the age of three-and-twenty Charles Templeton, my old tutor at Oxford, set himself to write a history of the Third French Republic. When I made his acquaintance, some thirty years later, he had satisfactorily concluded his introductory chapter on the origin of Kingship. At his death, three months ago, I understand that his notes on the precursors of Charlemagne were almost as complete as he desired. ‘It is so difficult to know where to start, Mr. Oakleigh,’ he used to say, as I picked my steps through the litter of notebooks that cumbered his tables, chairs, and floor.”[4]

But Mr. Templeton’s embarrassments were trifling in comparison with mine. Templeton was obviously a man of some leisure, whereas my literary hobbies have necessarily to be indulged more or less furtively in restaurants, railway trains, and during such hours and half-hours of opportunity as I can snatch from more pressing obligations. Moreover, Mr. Templeton could concentrate on one subject—History—whereas the scope of my studies compels me to keep on as good terms as may be with the exacting Muses of History, Mythology, Archæology, Philosophy, Religion, Romance, Symbolism, Numismatics, Folklore, and Etymology. I mention this not to extenuate any muzziness of thought, or sloppiness of diction, but to disarm by confession the charge that my work has been done hurriedly and here and there superficially.

With the facilities at my disposal I have endeavoured to the best of my abilities to concentrate a dozen rays on to one subject, and to mould into an harmonious and coherent whole the pith of a thousand and one items culled during the past seven years from day to day and noted from hour to hour. Differing as I do in some respects from the accepted conclusions of the best authorities, it is a further handicap to find myself in the position of Nehemiah the son of Hachaliah, who was constrained by force of circumstance to build with a sword in one hand and a trowel in the other.

To the heretic and the wayfarer it is, however, a comfortable reflection that what Authority maintains to-day it generally contradicts to-morrow.[5] Less than a century ago contemporary scholarship knew the age of the earth with such exquisite precision that it pronounced it to a year, declaring an exact total of 6000 years, and a few odd days.

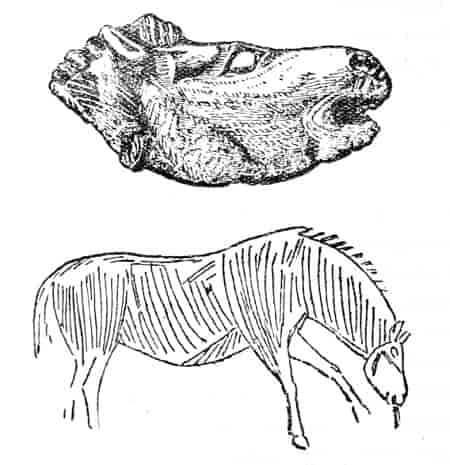

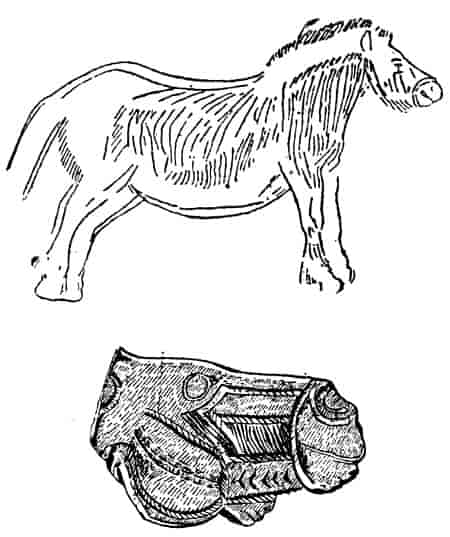

When the discoveries in Kent’s Cavern were laid before the scientific world, the authorities flatly denied their possibility, and the proofs that Man in Britain was contemporary with the mammoth, the lion, the bear, and the rhinoceros[6] were received with rudeness and inattention. Similarly the discovery of prehistoric implements in the gravel-beds at Abbeville was treated with inconsequence and insult, and it was upwards of twenty years before it was reluctantly conceded that: “While we have been straining our eyes to the East, and eagerly watching excavations in Egypt and Assyria, suddenly a new light has arisen in the midst of us; and the oldest relics of man yet discovered have occurred, not among the ruins of Nineveh or Heliopolis, not on the sandy plains of the Nile or the Euphrates, but in the pleasant valleys of England and France, along the banks of the Seine and the Somme, the Thames and the Waveney.”[7]

The fact is now generally accepted as proven by both anthropologists and archæologists, that the most ancient records of the human race exist not in Asia, but in Europe. The oldest documents are not the hieroglyphics of Egypt, but the hunting-scenes scratched on bone and ivory by the European cave-dwelling contemporaries of the mammoth and the woolly rhinoceros. Human implements found on the chalk plateaus of Kent have been assigned to a period prior to the glacial epoch, which is surmised to have endured for 160,000 years, from, roughly speaking, 240,000 to 80,000 years ago.

It is now also an axiom that the races of Europe are not colonists from somewhere in Asia, but that, speaking generally, they have inhabited their present districts more or less continuously from the time when they crept back gradually in the wake of the retreating ice.

“Written history and popular tradition,” says Sir E. Ray Lankester, “tell us something in regard to the derivation and history of existing ‘peoples,’ but we soon come to a period—a few thousand years back—concerning which both written statement and tradition are dumb. And yet we know that this part of the world—Europe—was inhabited by an abundant population in those remote times. We know that for at least 500,000 years human populations occupied portions of this territory, and that various races with distinguishing peculiarities of feature and frame, and each possessed of arts and crafts distinct from those characteristic of others, came and went in succession in those incredibly remote days in Europe. We know this from the implements, carvings, and paintings left by these successive populations, and we know it also by the discovery of their bones.”

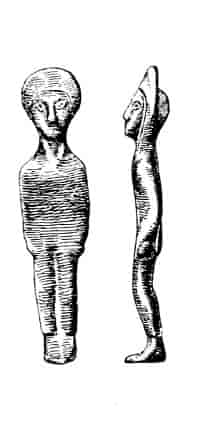

Anthropology, however, while admitting this unmeasurable antiquity for mankind, takes no count of the possibility of an amiable or cultured race in these islands prior to the coming of the Roman legions. It traces with equanimity the modern Briton evolving in unbroken sequence from the primitive cave-dweller, and it points with self-complacency to the fact that even as late as the Battle of Hastings some of Harold’s followers were armed with stone axes. There has, however, recently been unearthed near Maidstone the skull of a late palæolithic or early neolithic man, whose brain capacity was rather above the average of the modern Londoner. The forehead of this 15,000 year-old skull is well formed, there are no traces of a simian or overhanging brow, and the individual himself might well, in view of all physical evidence, have been a primeval sage rather than a primeval savage.

The high estimation in which the philosophy of prehistoric Briton was regarded abroad may be estimated from the testimony of Cæsar who states: “It is believed that this institution (Druidism) was founded in Britannia, and thence transplanted into Gaul. Even nowadays those who wish to become more intimately acquainted with the institution generally go to Britannia for instruction’s sake.”

It has been claimed for the Welsh that they possess the oldest literature in the oldest language in Europe. Giraldus Cambrensis, speaking of the Welsh Bards, mentions their possession of certain ancient and authentic books, but whether or not the traditionary poems which were first committed to writing in the twelfth century retain any traces of the prehistoric Faith is a matter of divided opinion. To those who are not experts in archaisms and are not enamoured of ink-spilling, the sanest position would appear to be that of Matthew Arnold, who observes in Celtic Literature: “There is evidently mixed here, with the newer legend, a detritus, as the geologists would say, of something far older; and the secret of Wales and its genius is not truly reached until this detritus, instead of being called recent because it is found in contact with what is recent, is disengaged, and is made to tell its own story.”[8]

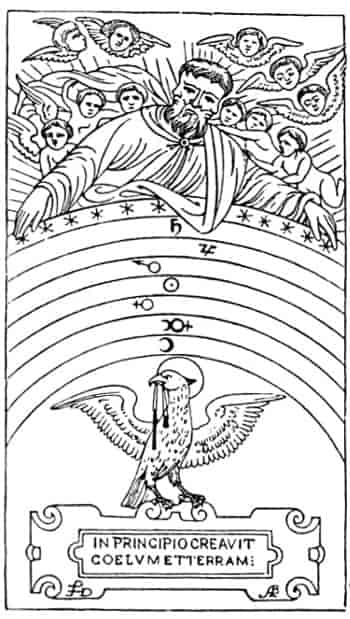

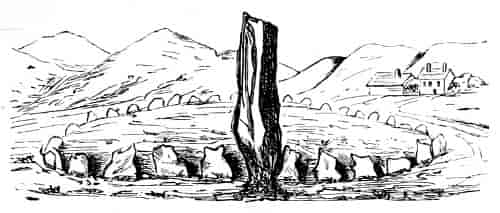

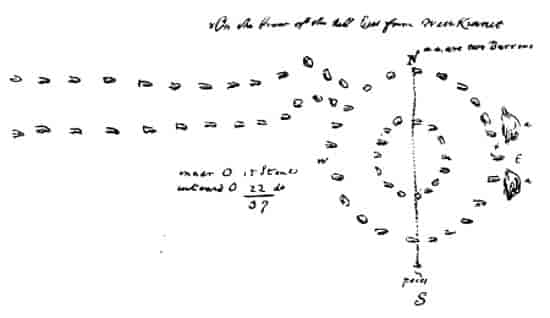

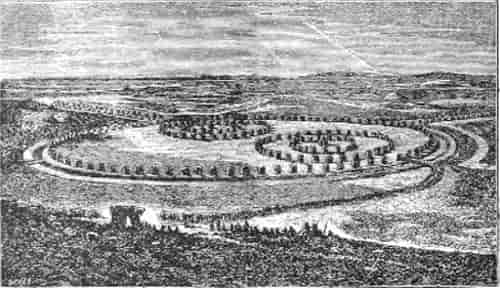

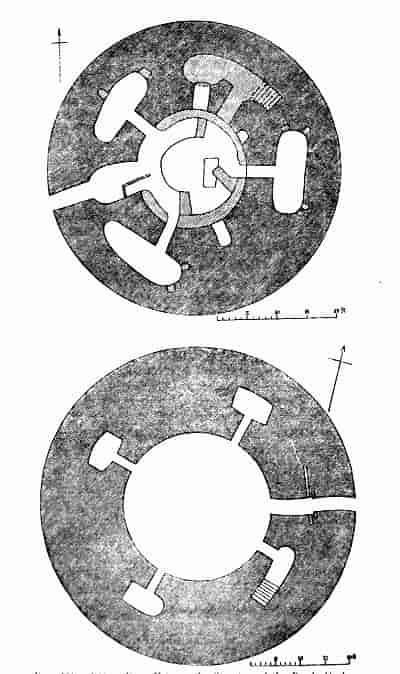

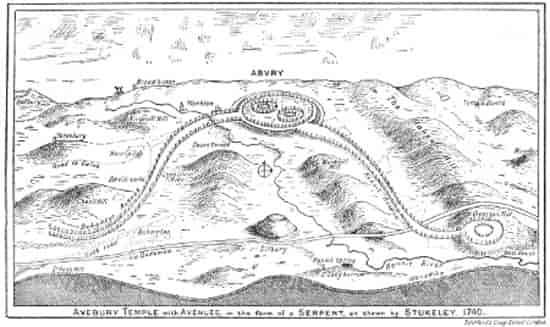

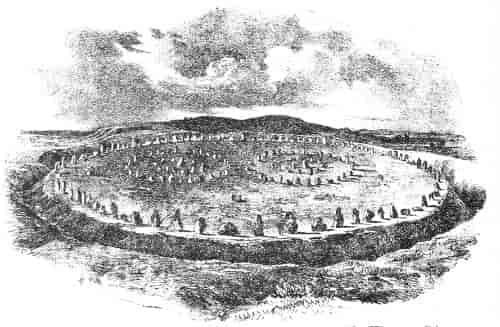

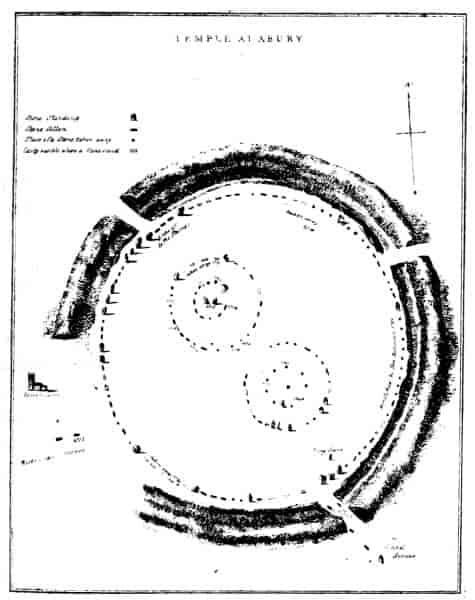

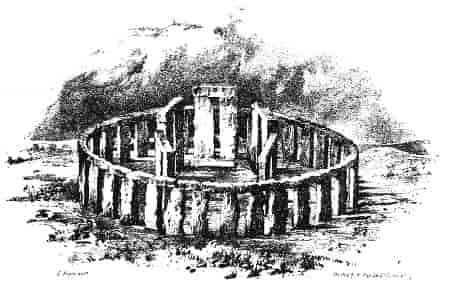

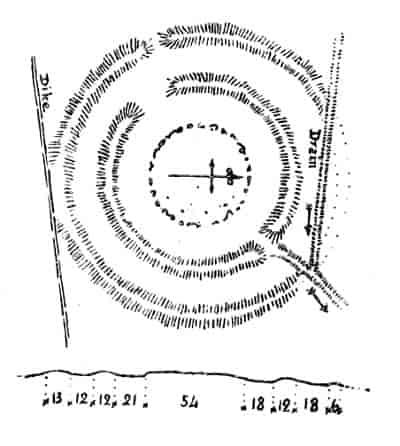

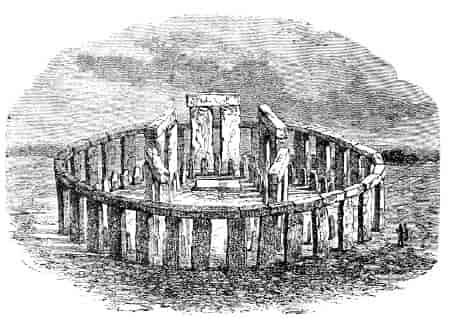

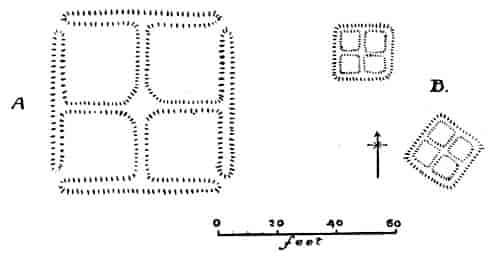

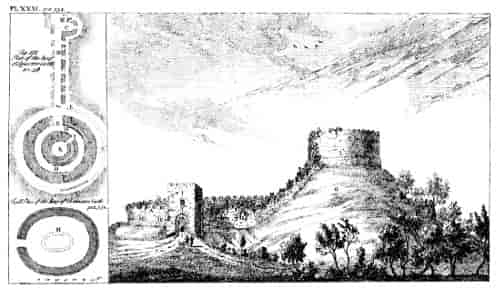

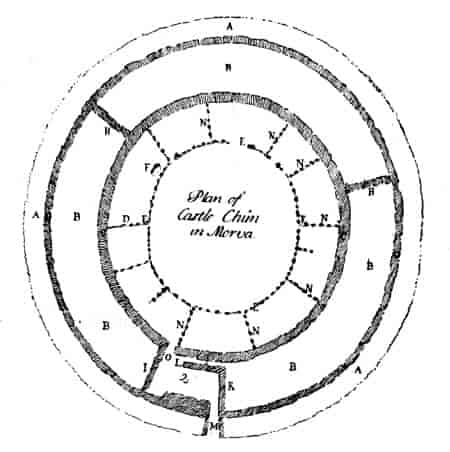

The word “founded,” as used by Cæsar, implies an antiquity for British institutions which is materially confirmed by the existence of such monuments as Stonehenge, and the more ancient Avebury. Whether these supposed “appendages to Bronze age burials” were merely sepulchral monuments, or whether they ever possessed any intellectual significance, does not affect the fact that Great Britain, and notably England, is richer in this class of monument than any other part of the world.[9]

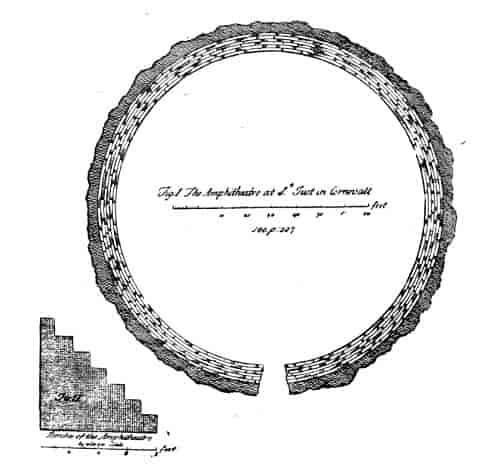

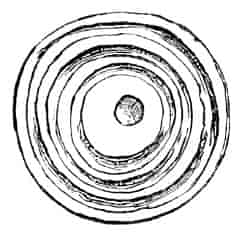

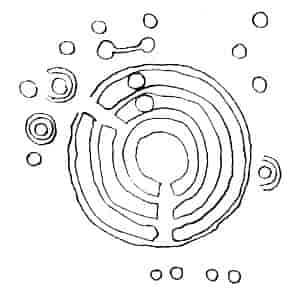

Circles being essentially and pre-eminently English it is disappointing to find the most modern handbook on Stonehenge stating: “In all matters of archæology it is constantly found that certain questions are better left in abeyance or bequeathed to a coming generation for solution”.[10] Every one sympathises with that weary feeling, but nevertheless the present generation now possesses quite sufficient data to enable it to shoulder its own responsibilities and to pass beyond the stereotyped and hackneyed formula “sepulchral monument”. I hold no brief on behalf of the Druids—indeed one must agree that the Celtic Druids were much more modern than the monuments associated with their name—nevertheless the theory that these far-famed philosophers were mere wise men or witch doctors, with perhaps a spice of the conjuror, is a modern misapprehension with which I am nowise in sympathy. Valerius Maximus (c. A.D. 20) was much better informed and therefore more cautious in his testimony: “I should be tempted to call these breeches-wearing gentry fools, were not their doctrine the same as that of the mantle-clad Pythagoras”.

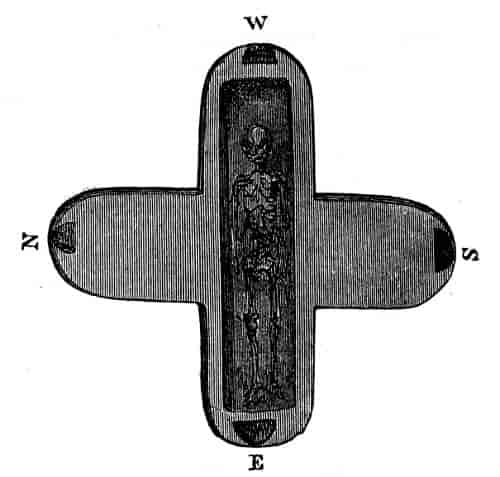

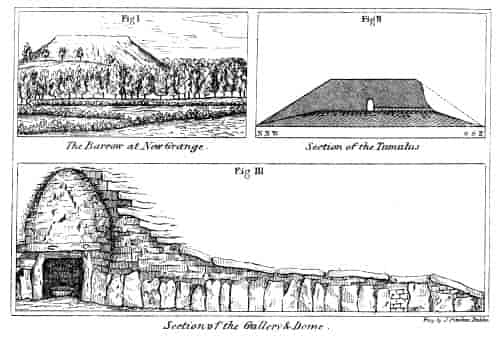

Druids or no Druids there must at some period in our past have been interesting and enterprising people in these islands. At Avebury, near Marlborough, is Silbury Hill, an earth mound, which is admittedly the vastest artificial hill in Europe. Avebury itself is said to constitute the greatest megalithic monument in Europe, and nowhere in the world are tumuli more plentiful than in Great Britain. On the banks of the Boyne is a pyramid of stones which, had it been situated on the banks of the Nile, would probably have been pronounced the oldest and most venerable of the pyramids. In the Orkneys at Hoy is almost the counterpart to an Egyptian marvel which, according to Herodotus, was an edifice 21 cubits in length, 14 in breadth, and 8 in height, the whole consisting only of one single stone, brought thither by sea from a place about 20 days’ sailing from Sais. The Hoy relic is an obelisk 36 feet long by 18 feet broad, by 9 feet deep. “No other stones are near it. ’Tis all hollowed within or scooped by human art and industry, having a door at the east end 2 feet square with a stone of the same dimension lying about 2 feet from it, which was intended no doubt to close the entrance. Within, there is at the south end of it, cut out, the form of a bed and pillow capable to hold two persons.”[11]

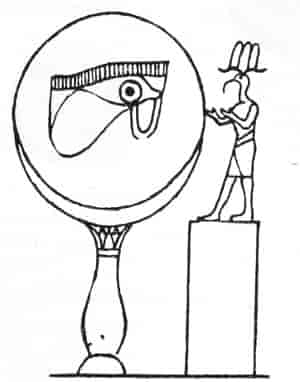

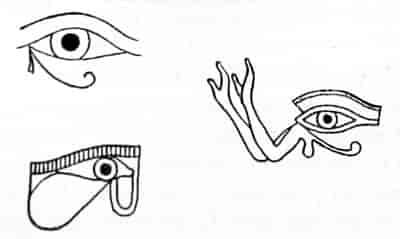

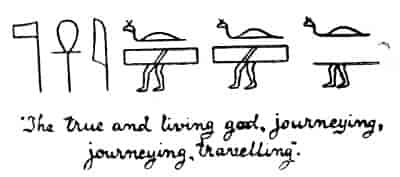

Sir John Morris-Jones has noted remarkable identities between the syntax of Welsh and that of early Egyptian: Gerald Massey, in his Book of the Beginnings, gives a list of 3000 close similarities between English and Egyptian words; and the astronomical inquiries of Sir Norman Lockyer have driven him to conclude: “The people who honoured us with their presence here in Britain some 4000 years ago, had evidently, some way or other, had communicated to them a very complete Egyptian culture, and they determined their time of night just in the same way that the Egyptians did”.

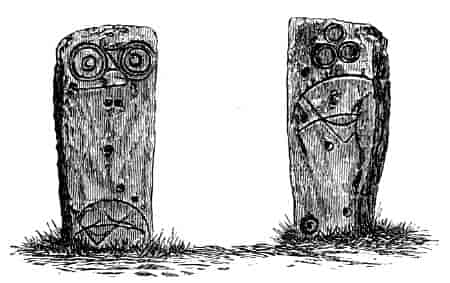

It used to be customary to attribute all the mysterious edifices of these islands, including stones inscribed with lettering in an unknown script, to hypothetical wanderers from the East. Nothing could have been more peremptory than the manner in which this theory was enunciated by its supporters, among whom were included all or nearly all the great names of the period. To-day there is a complete volte face upon this subject, and the latest opinion is that “not a particle of evidence has been adduced in favour of any migration from the East”.[12] When one remembers that only a year or two ago practically the whole of the academic world gave an exuberant and unqualified adherence to the theory of Asiatic immigration it is difficult to conceive a more chastening commentary upon the value of ex cathedra teaching.

Happily it was an Englishman[13] who, seeing through the futility of the Asiatic theory, first pointed out the now generally accepted fact that the cradle of Aryan civilisation, if anywhere at all, was inferentially in Europe. The assumption of an Asiatic origin was, however, so firmly established and upheld by the dignity of such imposing names that the arguments of Dr. Latham were not thought worthy of reply, and for sixteen years his work lay unheeded before the world. Even twenty years after publication, when the new view was winning many adherents, it was alluded to by one of the most learned Germans as follows: “And so it came to pass that in England, the native land of fads, there chanced to enter into the head of an eccentric individual the notion of placing the cradle of the Aryan race in Europe”.

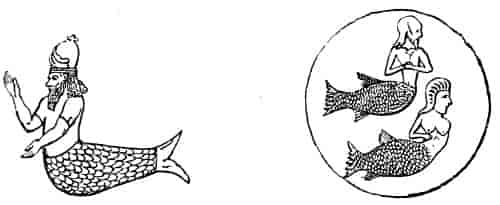

The whirligig of Time has now once again shifted the focus of archæological interest at the moment from Scandinavia to Crete, where recent excavations have revealed an Eldorado of prehistoric art. It is now considered that the civilisation of Hellas was a mere offshoot from that of Crete, and that Crete was veritably the fabulous Island of Atlantis, a culture-centre which leavened all the shores of the Mediterranean.

According to Sir Arthur Evans: “The high early culture, the equal rival of that of Egypt and Babylon, which began to take its rise in Crete in the fourth millennium before our era, flourished for some 2000 years, eventually dominating the Ægean and a large part of the Mediterranean basin. The many-storeyed palaces of the Minoan Priest-Kings in their great days, by their ingenious planning, their successful combination of the useful with the beautiful and stately, and last but not least, by their scientific sanitary arrangements, far outdid the similar works, on however vast a scale, of Egyptian or Babylonian builders.”

The sensational discoveries at Crete provide a wholly new standpoint whence to survey prehistoric civilisation, and they place the evolution of human art and appliances in the last Quaternary Period on a higher level than had ever previously been suspected.

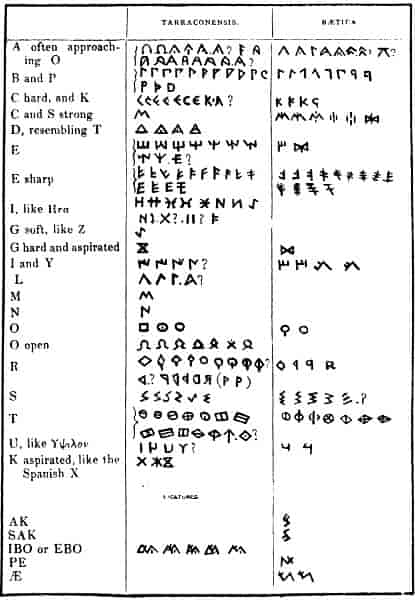

Not only have the findings in Crete revolutionised all previously current ideas upon Art, but they have also condemned to the melting-pot the cardinal article of belief that the alphabet reached us from Phœnicia. Prof. Flinders Petrie has now clearly demonstrated that even in this respect, “Beside the great historic perspective of the long use of signs in Egypt, other discoveries in Europe have opened entirely new ground. These signs are largely found used for writing in Crete, as a geometrical signary; and the discovery of the Karian alphabet, and its striking relation to the Spanish alphabet, has likewise compelled an entire reconsideration of the subject. Thus on all sides—Egyptian, Greek, and Barbarian—material appears which is far older and far more widespread than the Græco-Phœnician world; a fresh study of the whole material is imperatively needed, now that the old conclusions are seen to be quite inadequate.”

The striking connection between the Karian and the Spanish alphabet may be connoted with the fact that Strabo, mentioning the Turdetani whom he describes as the most learned tribe of all Spain, says they had reduced their language to grammatical rules, and that for 6000 years they had possessed metrical poems and even laws. Commenting upon this piece of precious information, Lardner ironically observed that although the Spaniards eagerly seized it as a proof of their ancient civilisation, they are sadly puzzled how to reconcile these 6000 years with the Mosaic chronology. He adds that discarding fable, we find nothing in their habits and manners to distinguish them from other branches of that great race, except, perhaps, a superior number of Druidical remains.[14]

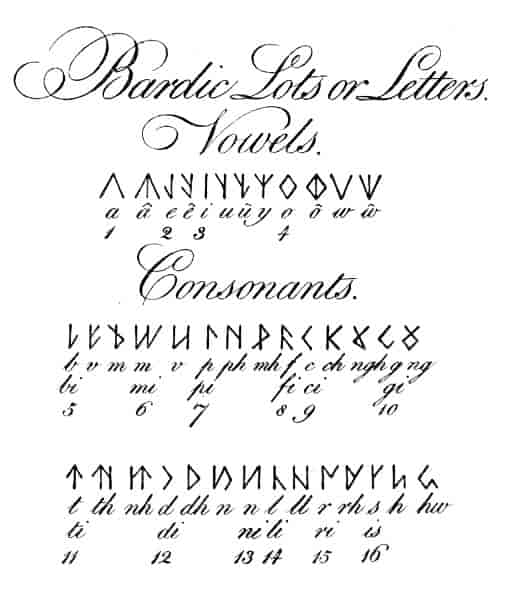

This “except” is noteworthy in view of the fact that the Celtiberian alphabet of Spain is extremely similar to the Bardic or Druidic alphabet of Britain, and also to the hitherto illegible alphabet of Ancient Crete.

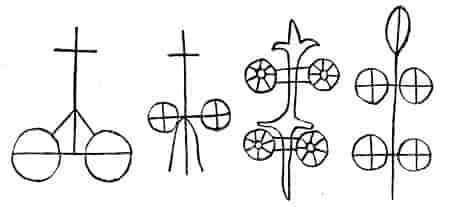

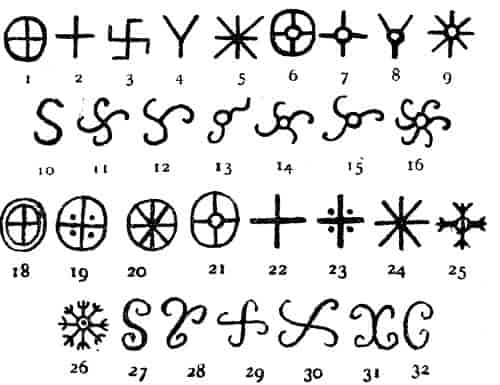

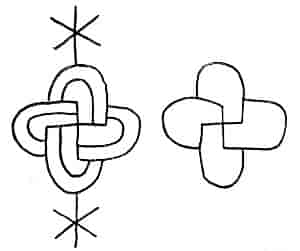

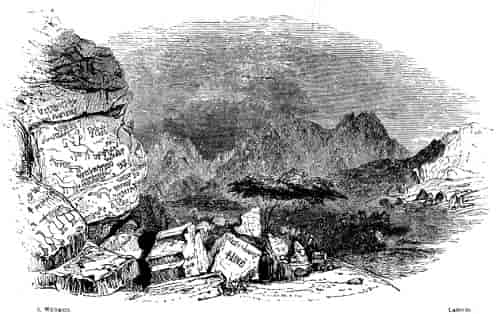

Cæsar has recorded that the Druids thought it an unhallowed thing to commit their lore to writing, though in the other public and private affairs of life they frequently made use of the Greek alphabet. That the Celts of Gaul possessed the art of writing cannot be questioned, and that Britain also practised some method of communication seems a probability. There are still extant in Scotland inscriptions on stones which are in characters now totally unknown. In Ireland, letters were cut on the bark of trees prepared for that purpose and called poet’s tables. The letters of the most ancient Irish alphabet are named after individual trees, and there are numerous references in Welsh poetry to a certain secret of the twigs which lead to the strong inference that “written” communication was first accomplished by the transmission of tree-sprigs.

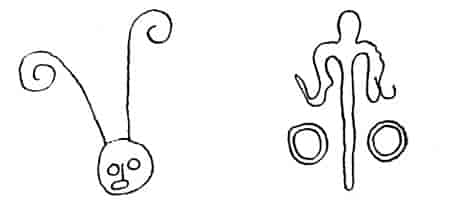

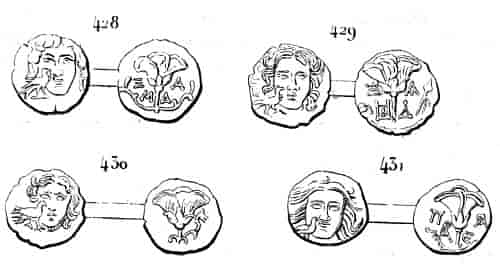

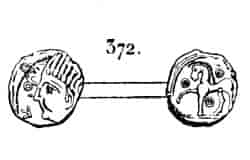

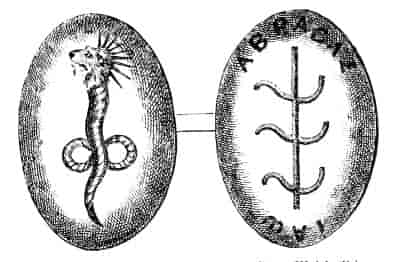

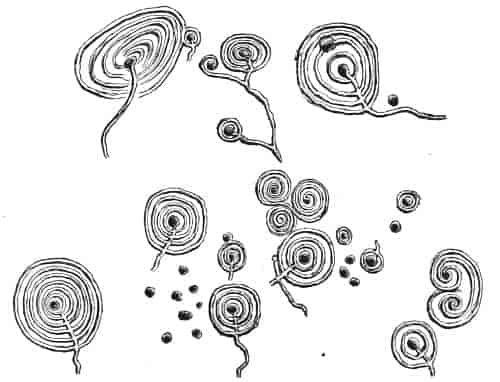

The alphabets illustrated on pages 14 and 15 have every appearance of being representations of sprigs, and it is a curious fact that not only in Ireland, but also in Arabia, alphabets of which every letter was named after trees[15] were once current.

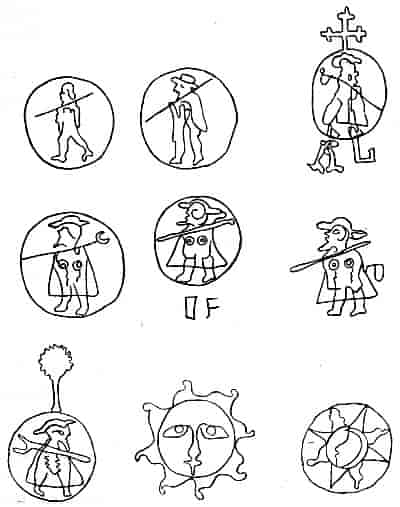

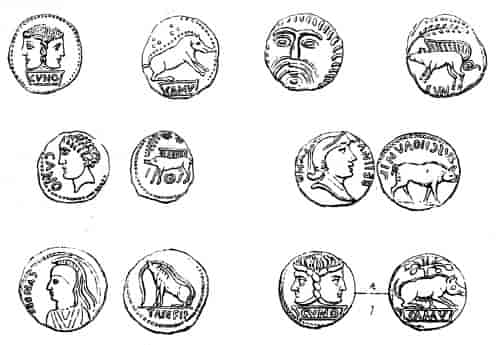

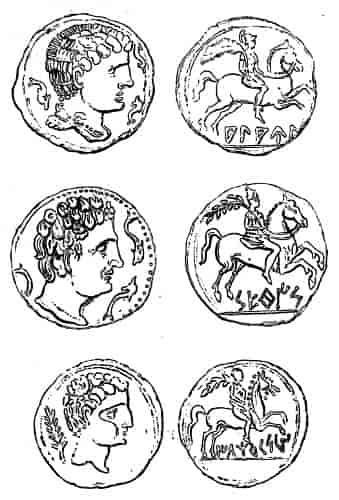

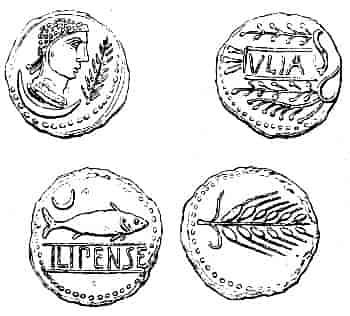

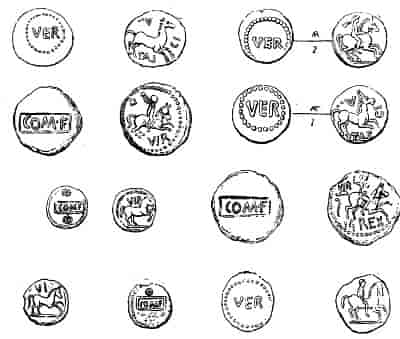

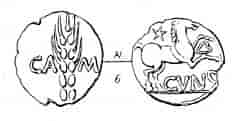

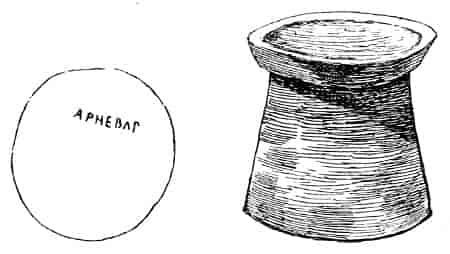

CELTIBERIAN ALPHABET, SHEWING THE DESCRIPTION OF CHARACTERS FOUND ON THE COINS OF TARRACONENSIS AND BÆTICA.

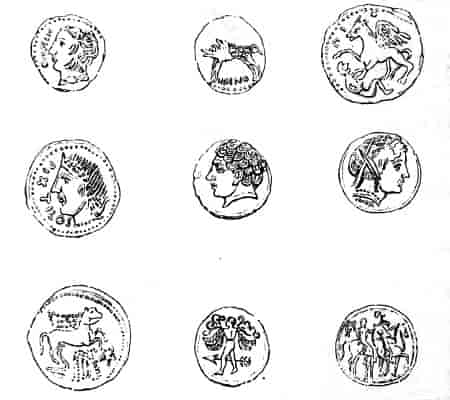

Fig. 2.—From Ancient Coins (Akerman, J. Y.).

In The Myths of Crete and Pre-Hellenic Europe, Dr. Mackenzie inquires: “By whom were Egyptian beads carried to Britain, between 1500 B.C. and 1400 B.C.? Certainly not the Phœnicians. The sea traders of the Mediterranean were at the time the Cretans. Whether or not their merchants visited England we have no means of knowing.”[16]

The material which I shall produce establishes a probability that the Cretans systematically visited Britain, and further that the tradition of the peopling of this island by men of Trojan race are well founded.

According to the immemorial records of the Welsh Bards: “There were three names imposed on the Isle of Britain from the beginning. Before it was inhabited its denomination was Sea-Girt Green-space; after being inhabited it was called the Honey Island, and after it was formed into a Commonwealth by Prydain, the Son of Aedd Mawr, it was called the Isle of Prydain. And none have any title therein but the nation of the Kymry. For they first settled upon it, and before that time no men lived therein, but it was full of bears, wolves, beavers, and bisons.”[17]

In the course of these essays I shall discuss the Kymry, and venture a few suggestions as to their cradle and community of memories and hopes. But behind the Kymry, as likewise admittedly behind the Cretans, are the traces of an even more primitive and archaic race. The earliest folk which reached Crete are described as having come with a form of culture which had been developed elsewhere, and among these neolithic settlers have been found traces of a race 6 feet in height and with skulls massive and shapely. Moreover Cretan beliefs and the myths which are based upon them are admittedly older than even the civilisation of the Tigro-Euphrates valley: and they belong, it would appear, to a stock of common inheritance from an uncertain culture centre of immense antiquity.[18]

The problem of Crete is indissolubly connected with that of Etruria, which was flourishing in Art and civilisation at a period when Rome was but a coterie of shepherds’ huts. Here again are found Cyclopean walls and the traces of some most ancient people who had sway in Italy at a period even more remote than the national existence of Etruria.[19]

We are told that the first-comers in Crete ground their meal in stone mortars, and that one of the peculiarities of the island was the herring-bone design of their wall buildings. In West Cornwall the stone walls or Giants’ Hedges are Cyclopean; farther north, in the Boscastle district, herring-bone walls are common, and in the neighbourhood of St. Just there are numerous British villages wherein the stone mortars are still standing.

The formula of independent evolution, which has recently been much over-worked, is now waning into disfavour, and it is difficult to believe otherwise than that identity of names, customs, and characteristics imply either borrowing or descent from some common, unknown source.

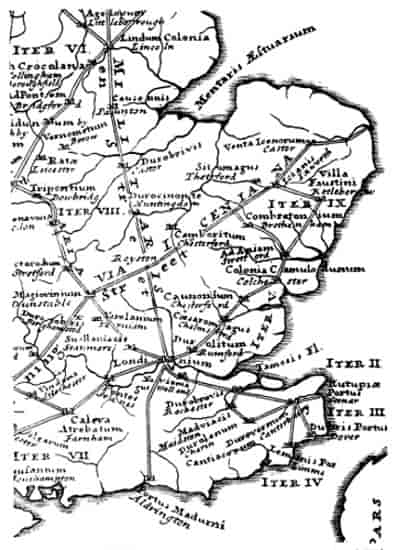

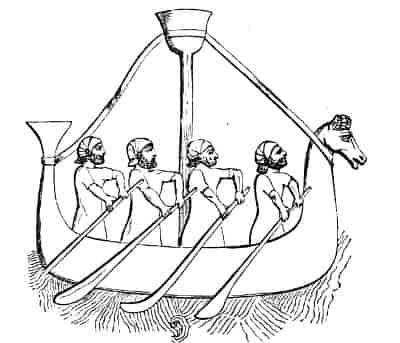

That the builders of our European tumuli and cromlechs were maritime arrivals is a reasonable inference from the fact that dolmens and cromlechs were built almost invariably near the sea.[20] These peculiar and distinctive monuments are found chiefly along the Western coasts of Britain, the Northern coast of Africa, in the isles of the Mediterranean, in the isolated, storm-beaten Hebrides, and in the remote islands of Asia and Polynesia.

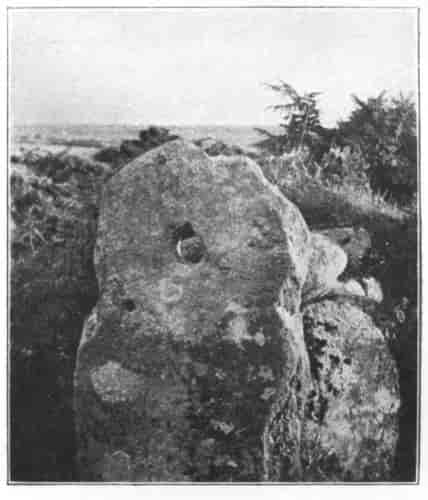

By whom was the Titanic art of cromlech-building brought alike to the British Isles and to the distant islands of the Pacific? By what guidance did frail barques compass such terrifying sea space? How were these adequately victualled for such voyages, and why were the mainlands ever quitted? How and why were the colossal stones of Stonehenge brought by ship from afar, floated down the broad waters of the prehistoric Avon, and dragged laboriously over the heights of Oare Hill? Who were the engineers who constructed artificial rocking stones and skilfully poised them where they stand to-day? “To suspend a stupendous mass of abnormous shape in such an equilibrium that it shall oscillate with the most trivial force and not fall without the greatest, is a problem unsolved so far as I know by modern engineers.”[21]

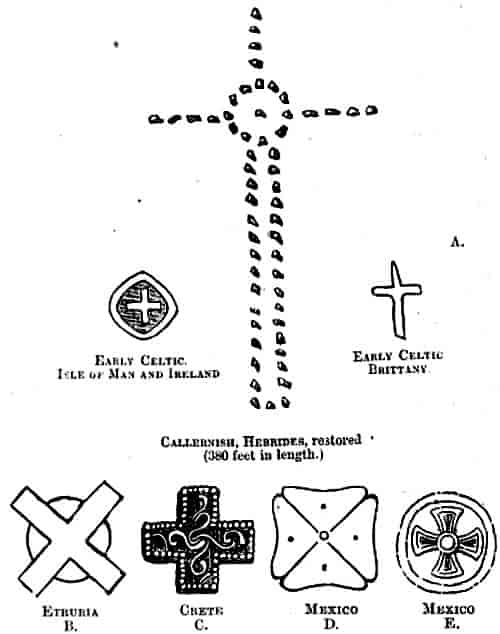

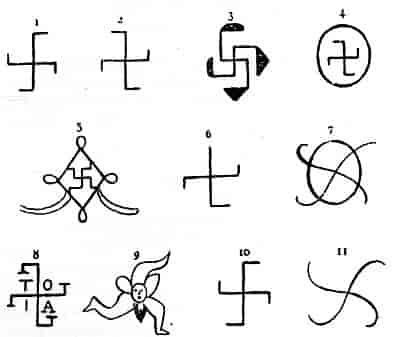

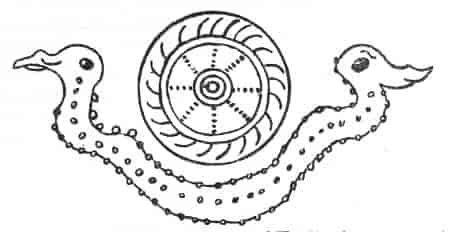

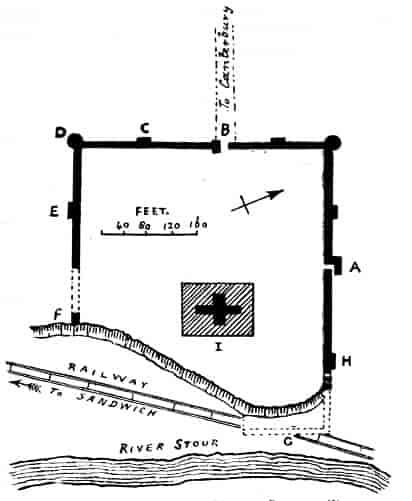

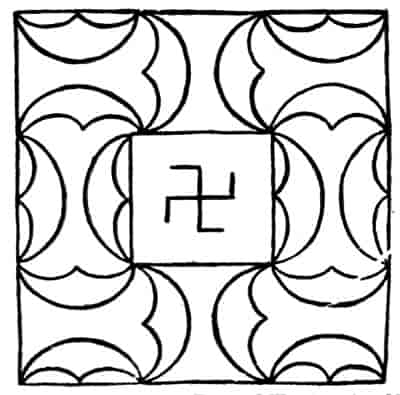

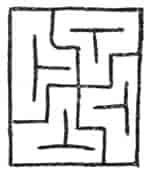

Who were the indefatigable people who, prior to all record, reclaimed the marshes of the Thames-mouth by an embankment which is intact to-day all round the river coast of Kent and Essex? Who were the horticulturists who evolved wheat and other cereals from unknown grasses and certain lilies from their unknown wild? And who were the philosophers who spun a delicate gossamer of fairy-tales over the world, and formulated the cosmic ideas which are in many extraordinary respects common alike to primitive and more advanced peoples? And why is the symbol generally entitled the Swastika cross found not only under the ruins of the most ancient Troy but also in the Thames at Battersea, and elsewhere from China to Zimbabwe? How is it that Ireland, that remote little outpost of Europe, possesses more Celtic MSS. than all the rest of Celtic Europe put together?

The most rational explanation of these and similar queries is seemingly a consideration of the almost world-wide tradition of a lost island, the home of a scientific world-wandering race. The legend of submerged Atlantis was related to Solon by an Egyptian priest as being historic fact, and the date of the final catastrophe was definitely set down by Plato from information given to Solon as having been about 9000 B.C. Solon was neither a fool himself nor the man to suffer fools gladly. It is admitted by geology that there actually existed a large island in the Atlantic during tertiary times, but this we are told is a pure coincidence and it is impossible to suppose any tradition existing of such an island or land.

Science has very generally denied the credibility of tradition, yet tradition has almost invariably proved truer than contemporary scholarship. Scholarship denied the possibility of finding Troy, notwithstanding the steady evidence of tradition to the mound at Hissarlik where it was eventually disclosed. Even when Schliemann had uncovered the lost city the scientists of every European capital ridiculed his pretensions, and it was only gradually that they ungraciously yielded to the irresistible evidence of their physical senses. Science similarly denied the possibility of buried cities at the foot of Vesuvius, yet popular tradition always asserted the existence of Pompeii and Herculaneum; indeed, contemporary science has so consistently scouted the possibility of every advance in discovery that mere airy dismissal is not now sufficient to discredit either the Atlantean, or any other theory. From China to Peru one finds the persistent tradition of a drowned land, a story which is in itself so preposterous as unlikely to arise without some solid grounds of reality. Thierry has observed that legend is living tradition, and three times out of four it is truer than what we call history. Sir John Morris Jones would seemingly endorse this proposition, for he has recently contended that tradition is itself a fact not always to be disposed of by the hasty assumption that all men are liars.[22]

The Irish have their own account of the Flood, according to which three ships sailed for Ireland, but two of them foundered on the way. The Welsh version runs that the first of the perilous mishaps which occurred in Britain was “The outburst of the ocean ‘Torriad lin lion,’ when a deluge spread over the face of all lands, so that all mankind were drowned with the exception of Duw-van and Duw-ach, the divine man and divine woman, who escaped in a decked ship without sails; and from this pair the island of Prydain was completely re-peopled”.

Correlated with this native version is a peculiar and, so far as my information goes, a unique tradition that previous disasters had taken place, causing the destruction of animals and vegetables then existing, of which whole races were irrevocably lost. This tradition, which is in complete harmony with the discoveries of modern geology, is thus embodied in the thirteenth Triad: “The second perilous mishap was the terror of the torrent-fire, when the earth was cloven down to the abyss, and the majority of living things were destroyed”.

It is a singular coincidence that evidence of a prehistoric torrent-fire exists certainly in Ireland, where bog-buried forests have been unearthed exhibiting all the signs of a flowing torrent of molten fire or lava. According to the author of Bogs and Ancient Forests, when the Bog of Allen in Kildare was cut through, oak, fir, yew, and other trees were found buried 20 or 30 feet below the surface, and these trees generally lie prostrated in a horizontal position, and have the appearance of being burned at the bottom of their trunks and roots, fire having been found far more powerful in prostrating those forests than cutting them down with an axe; and the great depth at which these trees are found in bogs, shows that they must have lain there for many ages.[23]

No ordinary or casual forest fire is capable of prostrating an oak or fir tree, and the implement which accomplished such terrific devastation must have been something volcanic and torrential in its character.

I am, however, not enamoured of the Atlantean or any other theory. My purpose is rather to collate facts, and as all theorising ends in an appeal to self-evidence, it is better to allow my material, for much of which I have physically descended into the deeps of the earth, to speak for itself:—we must believe the evidence of our senses rather than arguments, and believe arguments if they agree with the phenomena.[24]

Although my concordance of facts is based upon evidence largely visible to the naked eye, in a study of this character there must of necessity be a disquieting percentage of “probablys” and “possiblys”. This is deplorable, but if license be conceded in one direction it cannot be withheld in another. The extent to which guess-work is still rampant in etymology will be apparent in due course; the extent to which it is allowed license in anthropology may be judged from such reveries as the following: “Did any early members of the human family commit suicide? Probably they did; the feeble, the dying, the maimed, the weak-headed, the starving, the jealous, would be tired of life; these would throw themselves from heights or into rivers, or stab themselves or cut their throats with large and keen-edged knives of flint.”[25]

Although my own inquiries deal intimately with graves and names and epitaphs, it still seems to me a possibility that the brains which fashioned exquisitely barbed fish-hooks out of flint, and etched vivid works of art upon pebble, may also have been capable of poetic and even magnanimous ideas. It is quite certain that the artistic sense is superlatively ancient, and it is quite unproven that the lives of these early craftsmen were protracted nightmares.

Although not primarily written with that end, the present work will inter alia raise not a few doubts as to the accuracy of Green’s dictum: “What strikes us at once in the new England is that it was the one purely German nation that rose upon the wreck of Rome”. In the opinion of this popular historian the holiest spot in all these islands ought in the eyes of Englishmen to be Ebbsfleet, the site where in Kent the English visitors first landed, yet inconsequently he adds: “A century after their landing the English are still known to their British foes only as ‘barbarians,’ ‘wolves,’ ‘dogs,’ ‘whelps from the kennel of barbarism,’ ‘hateful to God and man’. Their victories seemed victories for the powers of evil, chastisement of a divine justice for natural sin.”[26]

It is an axiom among anthropologists that race characteristics do not change and that tides of immigration are more or less rapidly absorbed by the aboriginal and resident stock. Assuredly the characteristics of the German tribes have little changed, and it is extraordinary how from the time of Tacitus they have continued to display from age to age their time-honoured peculiarities. Invited and welcomed into this country as friends and allies, “in a short time swarms of the aforesaid nations came over into the island, and they began to increase so much that they became terrible to the natives themselves who had invited them”.[27]

According to Bede the first symptoms of the frightfulness which was to come were demands for larger rations, accompanied by the threat that unless more plentiful supplies were brought them they would break the confederacy and ravage all the island. Nor were they backward in putting their threats in execution. Just as the Germans ruined Louvain so the Angles razed Cambridge,[28] and in the words of Layamon “they passed to and fro the country carrying off all they found”. Already in the times of Tacitus famous for their frantic Hymns of Hate, so again we find Layamon recording “they breathed out threatenings and slaughter against the folk of the country”. Indeed Layamon uses far stronger expressions than any of those quoted by Green, and the British chronicler almost habitually refers to the alien intruders as “swine,” and “the loathest of all things”.

Instead, therefore, of being thrilled into ecstasy by the landing of the Germans at Ebbsfleet, one may more reasonably regard the episode as untoward and discreditable. It is more satisfactory to contemplate the return in the train of Duke William of Normandy of those numerous Britons who “with sorrowful hearts had fled beyond the seas,” and to appreciate that by the Battle of Hastings the temporary ascendancy of Germanic kultur was finally and irrevocably destroyed.

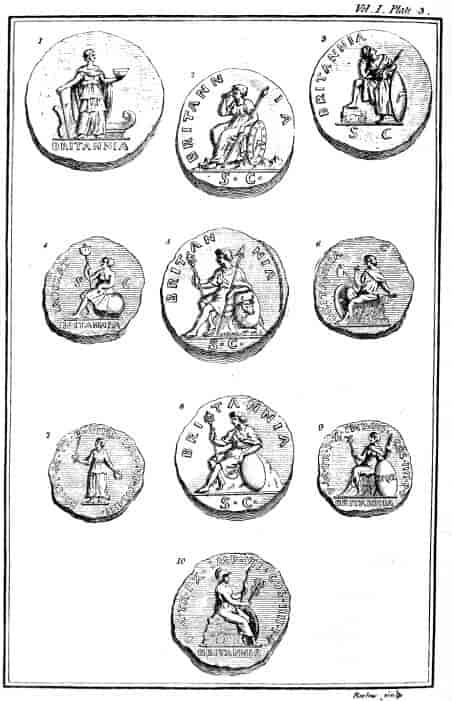

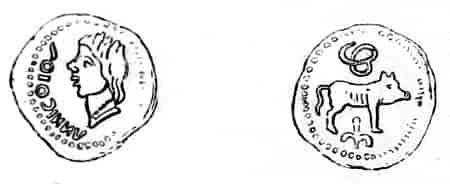

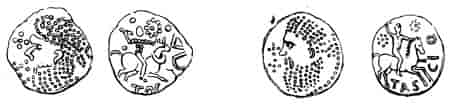

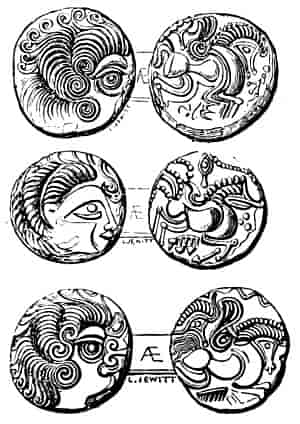

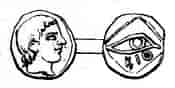

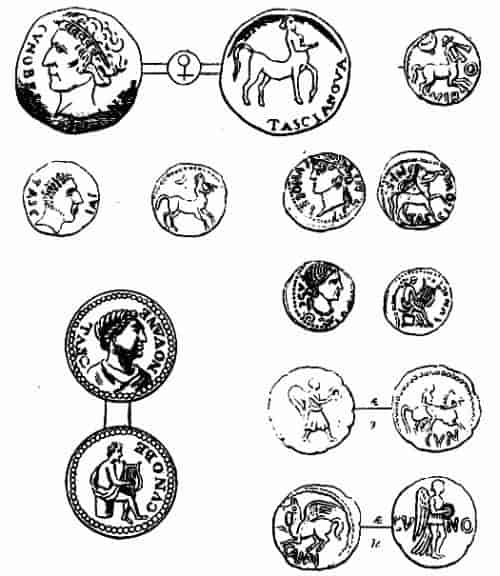

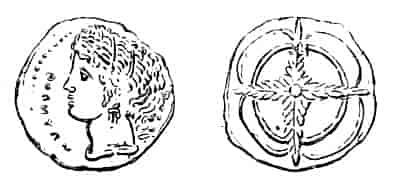

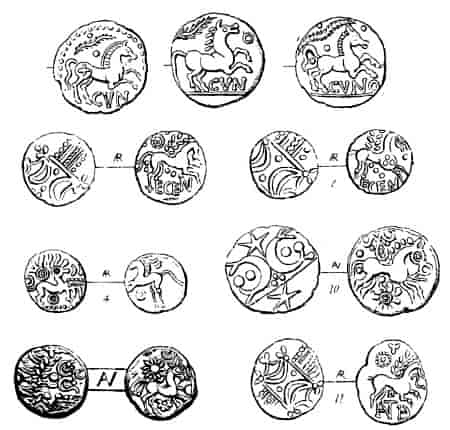

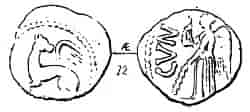

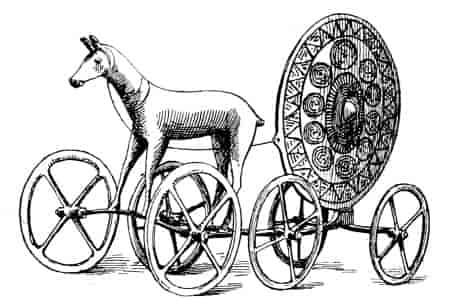

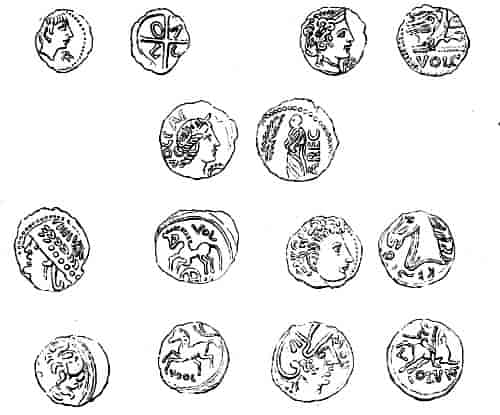

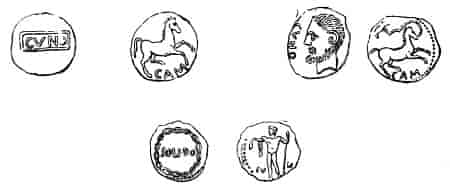

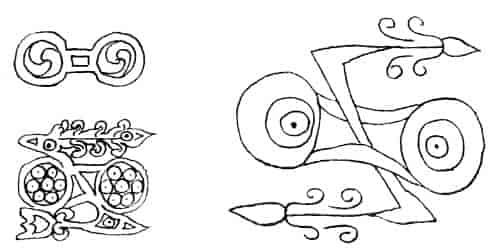

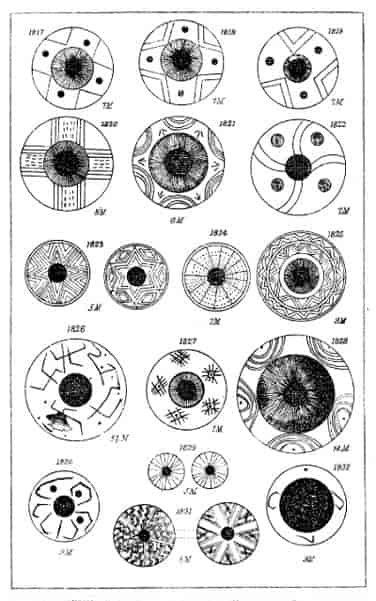

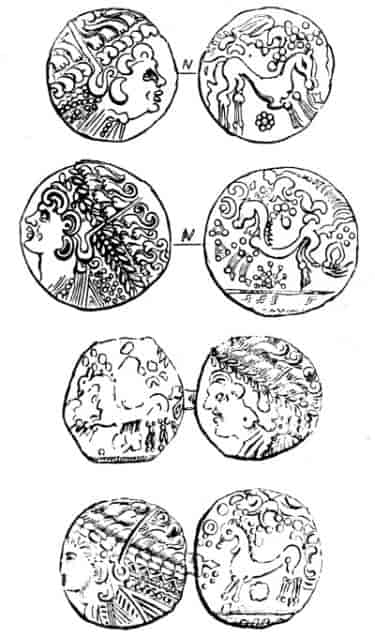

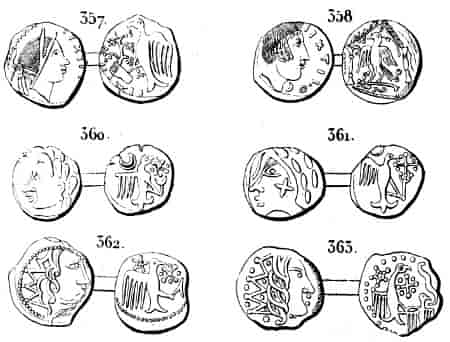

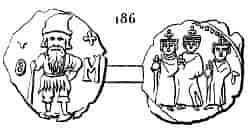

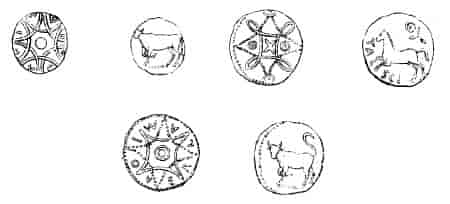

It is observed by Green that the coins which we dig up in our fields are no relics of our English fathers but of a Roman world which our fathers’ sword swept utterly away. This is sufficiently true as regards the Saxon sword, but as some of the native coins in question are now universally assigned to a period 200 to 100 years earlier than the first coming of the Romans, it is obvious that there must have been sufficient civilisation then in the country to require a coinage, and that the native Britons cannot have been the poor and backward barbarians of popular estimation.

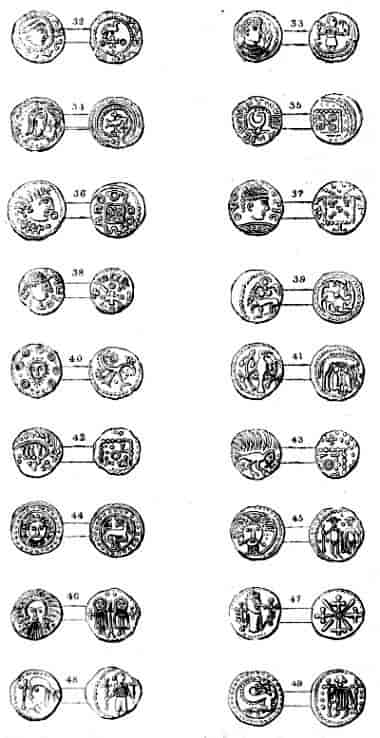

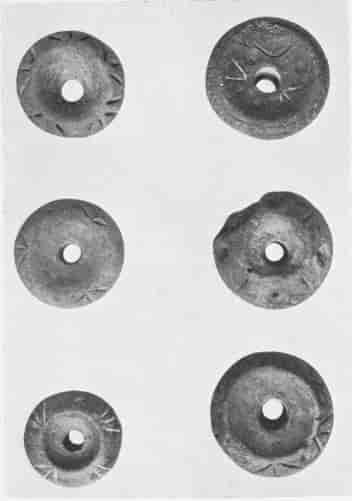

A coin is an excessively hard fact, and should be of just as high interest to the historian as a well-formed skull or any other document. To Englishmen our prehistoric coinage—a national coinage “scarcely if at all inferior to that of contemporary Rome”—[29] ought to possess peculiar and special interest, for it is practically in England alone that early coins have been discovered, and neither Scotland, Wales, nor Ireland can boast of more than very few. It is, however, an Englishman’s peculiarity that possessing perhaps the most interesting history, and some of the most fascinating relics in the world, he is either too modest or too dull to take account of them. The plate of coins illustrated on page 364, represents certain sceattae which, according to Hawkins, may have been struck during the interval between the departure of the Romans and the arrival of the Saxons. One would at least have thought that such undated minor-monuments would have possessed per se sufficient interest to ensure their careful preservation. Yet, according to Hawkins, these rude and uncouth pieces are scarce, “because they are rejected from all cabinets and thrown away as soon as discovered”.[30]

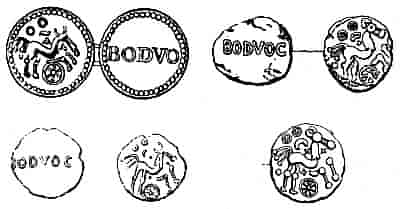

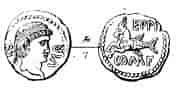

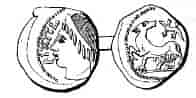

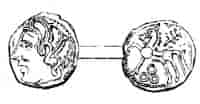

It is the considered opinion of certain British numismatists that not only all English but also Gaulish coins are barbarous and degraded imitations of a famous Macedonian original which at one time circulated largely in Marseilles. This supposititious model is illustrated on page 394, and the reader can form his own opinion as to whether or not the immense range of subjects which figure on our native money could by any possibility have unconsciously evolved from carelessness. Sir John Evans, by whom this theory was, I believe, first put forward, is himself at times hard-driven to defend it; nevertheless he does not hesitate to maintain: “The degeneration of the head of Apollo into two boars and a wheel, impossible as it may at first appear, is in fact but a comparatively easy transition when once the head has been reduced into a form of regular pattern”.[31]

My irregularity carries me to the extent of contending that our native coins, crude and uncouth as some of them may be, are in no case imitations but are native work reflecting erstwhile national ideas. The weird designs and what-nots which figure on these tokens almost certainly were once animated by meanings of some sort: they thus constitute a prehistoric literature expressed in hieroglyphics for the correct reading of which one must, in the words of Carlyle, consider History with the beginnings of it stretching dimly into the remote time, emerging darkly out of the mysterious eternity, the true epic poem and universal divine scripture.

According to Tacitus the British, under Boudicca, brought into the field an incredible multitude; that Cæsar was impressed by the density of the inhabitants may be gathered from his words: “The population is immense; homesteads closely resembling those of the Gauls are met with at every turn, and cattle are very numerous”.[32] That the handful of Roman invaders eliminated the customs and traditions of a vast population is no more likely than the supposition that British occupation has eradicated or even greatly interfered with the native faiths of India.

It is generally admitted that the Romans were most tolerant of local sensibilities, and there is no reason to assume that existing British characteristics were either attacked or suppressed. To assume that some hundreds of years later the advent of a few boat-loads of Anglo-Saxon adventurers wiped out the Romano-British inhabitants and eradicated all customs, manners, and traditions is an obvious fallacy under which the evidence of folklore does not permit us to labour. The greater probability is that the established culture imposed itself more or less upon the new-comers, more particularly in those remote districts which it was only after hundreds of years that the Saxons, by their conventional policy of peaceful penetration, punctuated by flashes of frightfulness, succeeded in dominating.

Even after the Norman Conquest there are circumstances which point to the probability that the Celtic population was much larger and more powerful than is usually supposed. Of these the most important is the fact that the signatures to very early charters supply us with names of persons of Celtic race occupying positions of dignity at the courts of Anglo-Saxon kings.[33]

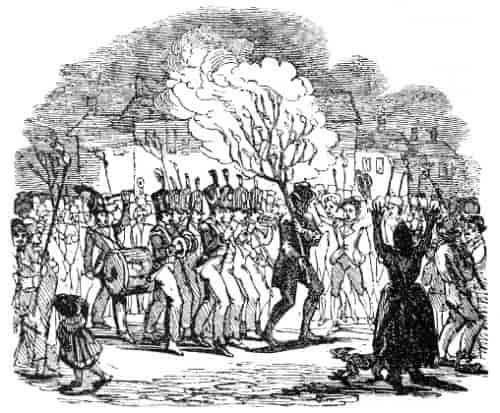

The force of custom and the apparently undying continuance of folk-memory are among the best attested phenomena of folklore. It was remarked by the elder Disraeli that tradition can neither be made nor destroyed, and if this be true in general it is peculiarly true of the stubborn and pig-headed British. Our churches stand to-day not only on the primeval inconvenient hill-sites, but frequently within the time-honoured earthwork, or beside the fairy-well. On Palm Sunday the villagers of Avebury still toil to the summit of Silbury Hill, there to consume fig cakes and drink sugared water; and on the same festival the people even to-day march in procession to the prehistoric earthwork on the top of Martinshell Hill. Our country fairs are generally held near or within a pagan earthwork, and instance after instance might be adduced all pointing to the immortality of custom and the persistent sanctity of pagan sites.

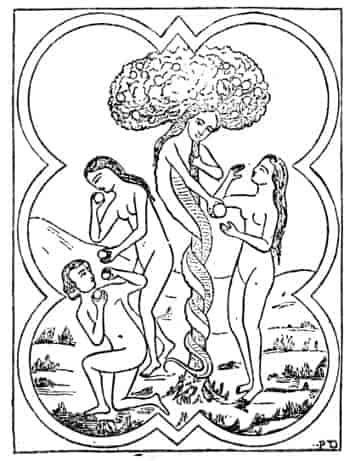

In the sixth century of our era the monk Gildas referred complacently but erroneously to the ancient British faith as being dead. “I shall not,” he says, “enumerate those diabolical idols of my country, which almost surpassed in number those of Egypt, and of which we still see some mouldering away within or without the deserted temples, with stiff and deformed features as was customary. Nor will I cry out upon the mountains, fountains, or hills, or upon the rivers, which now are subservient to the use of men, but once were an abomination and destruction to them, and to which the blind people paid divine honour.”

Notwithstanding the jeremiads of poor Gildas[34] the folk-faith survived; indeed, as Mr. Johnson says, the heathen belief has been present all the time, and need not greatly astonish us since the most advanced materialist is frequently a victim of trivial superstitions which are scouted by scientific men as baseless and absurd.

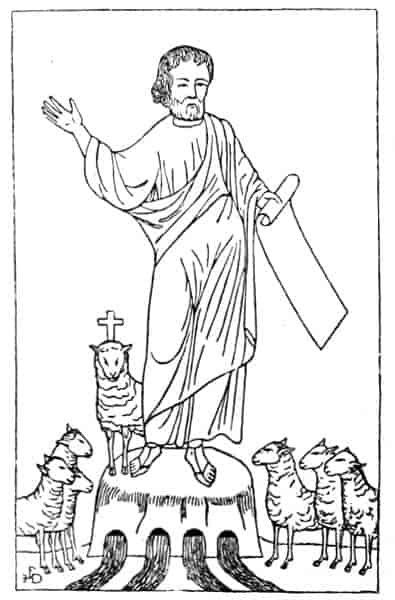

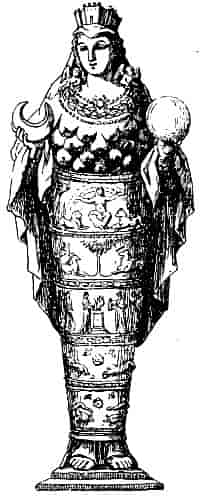

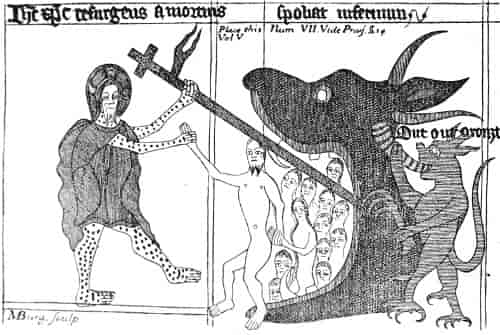

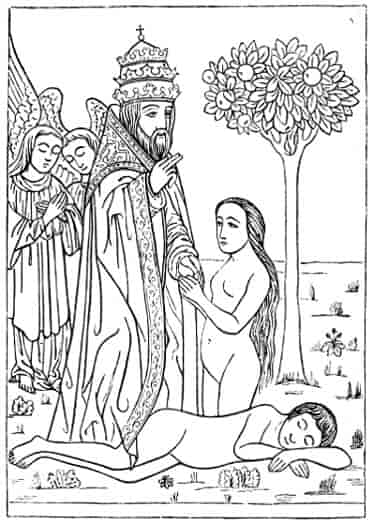

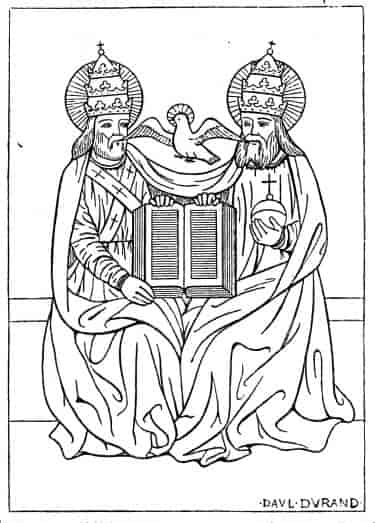

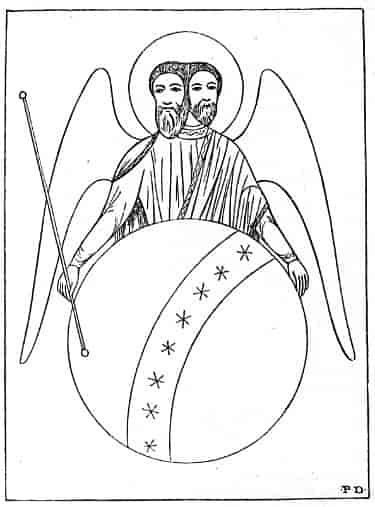

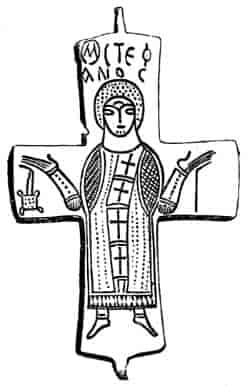

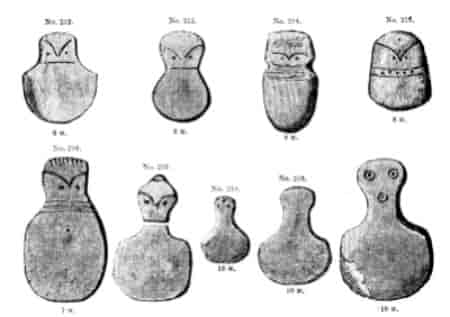

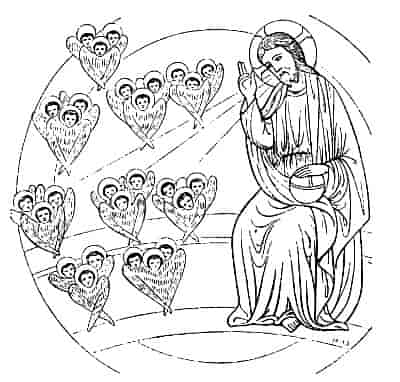

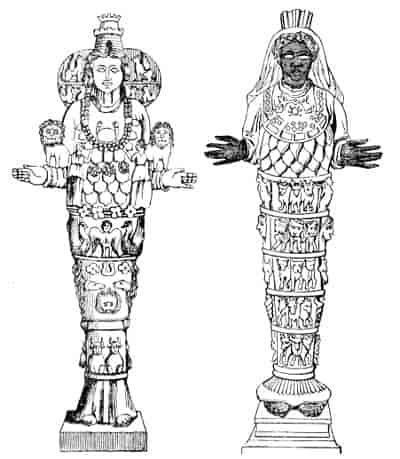

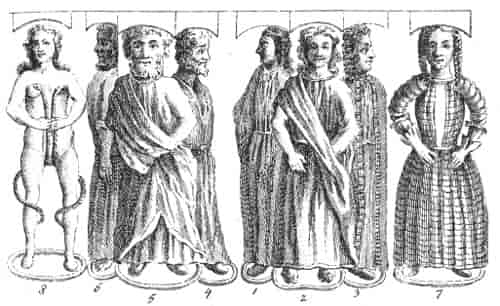

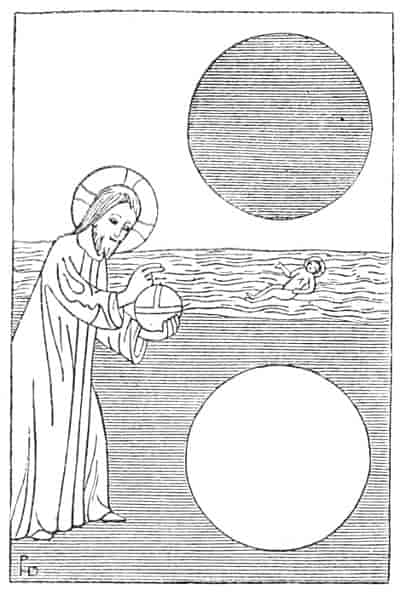

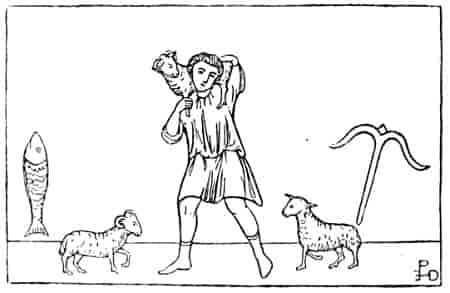

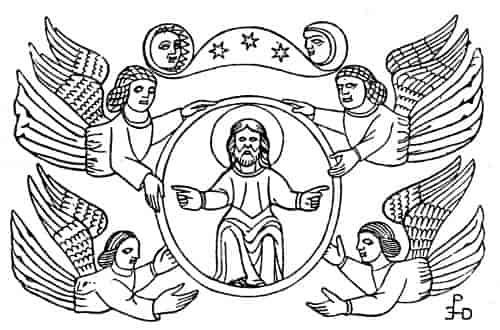

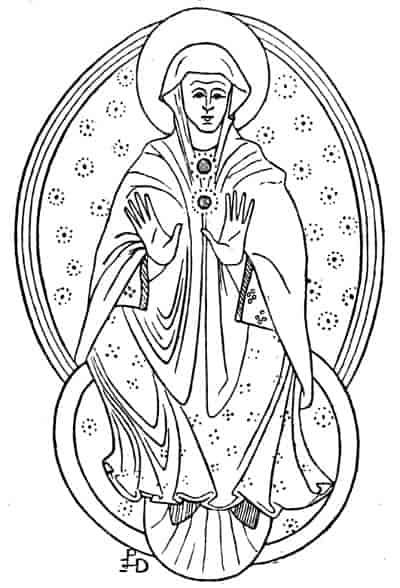

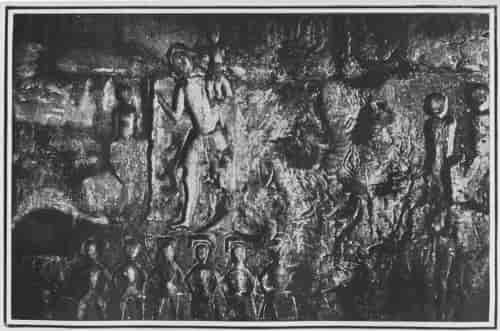

The Augustine of Canterbury, who is recorded to have baptised on one day 10,000 persons in the river Swale, recommended with pious ingenuity that the heathen temples should not be destroyed, but converted to the honour of Christ by washing their walls with holy water and substituting holy relics and symbols for the images of the heathen gods. This is an illuminating sidelight on the methods by which the images of the heathen idols were gradually transformed into the images of Christian saints, and there is little doubt that as the immemorial shrines fell into ruin and were rebuilt and again rebuilt, the sacred images were scrupulously relimned.

Even to-day, after 2000 years of Christian discipline, the clergy dare not in some districts interfere with the time-honoured tenets of their parishioners. In Normandy and Brittany the priests, against their inclination, are compelled to take part in pagan ceremonials,[35] and in Spain quite recently an archbishop has been nearly killed by his congregation for interdicting old customs.[36]

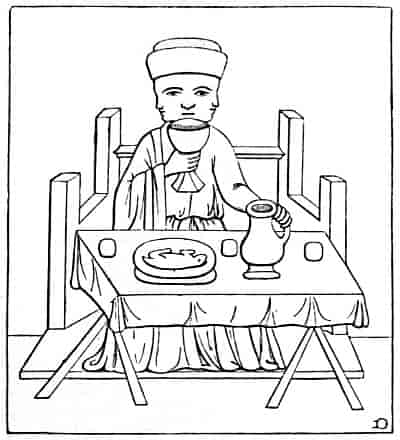

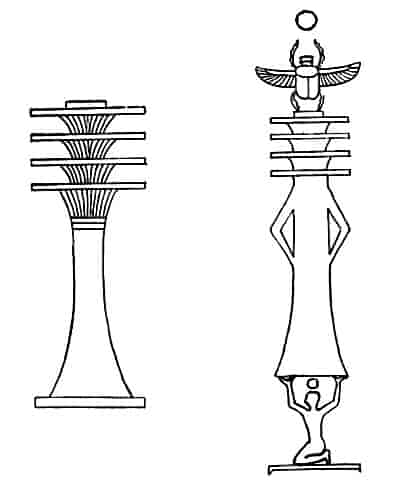

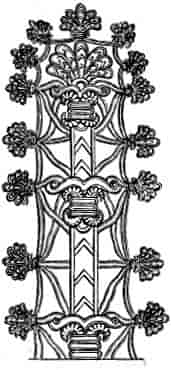

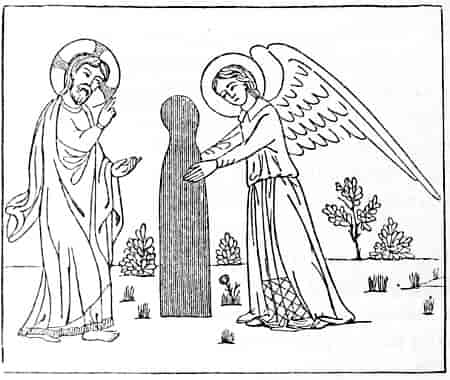

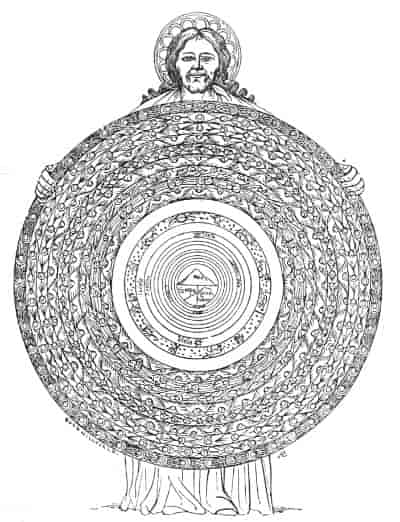

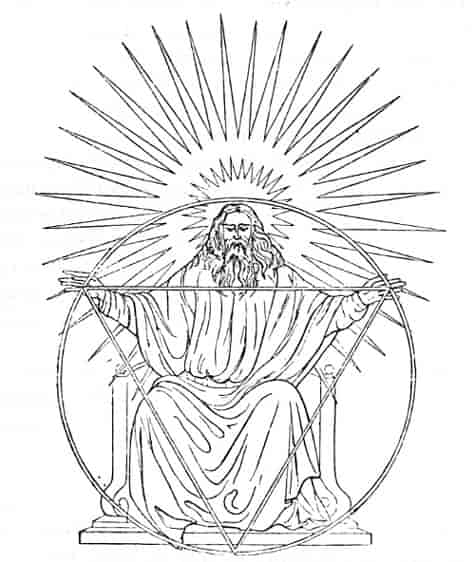

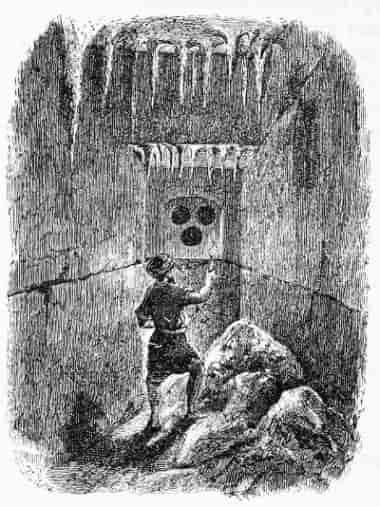

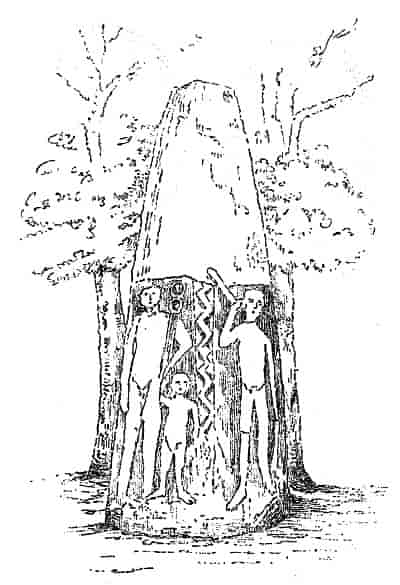

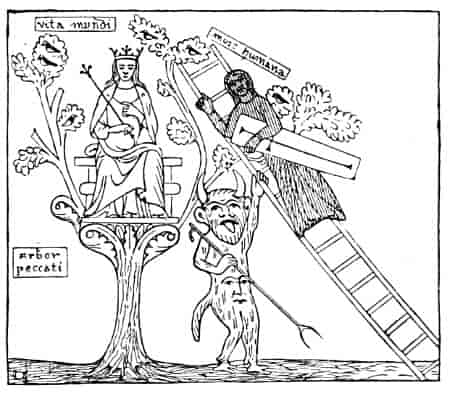

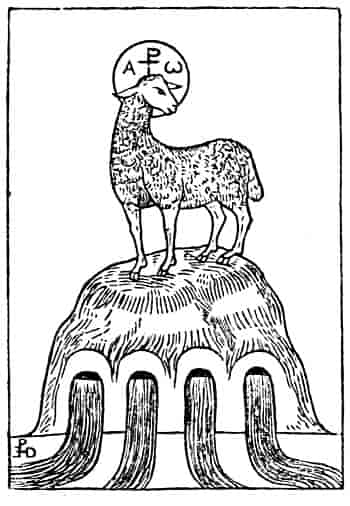

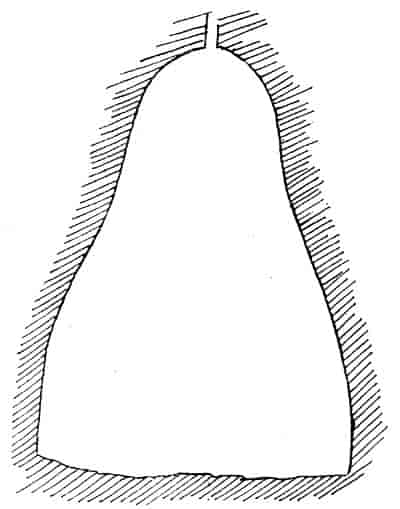

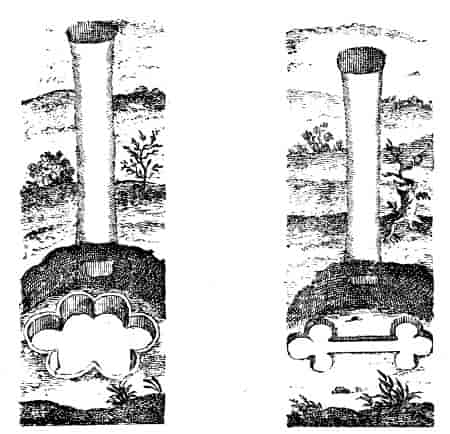

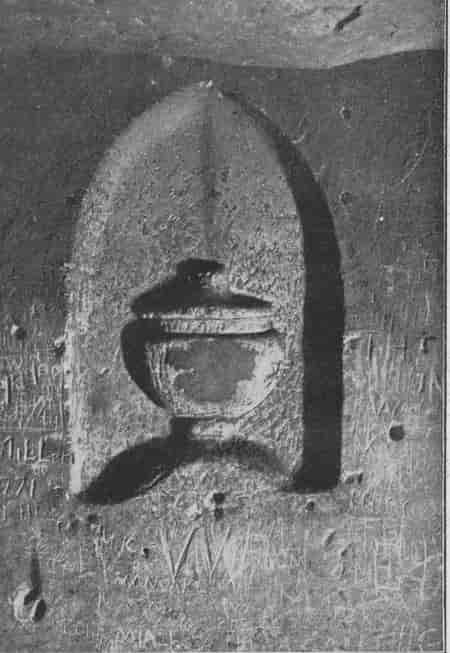

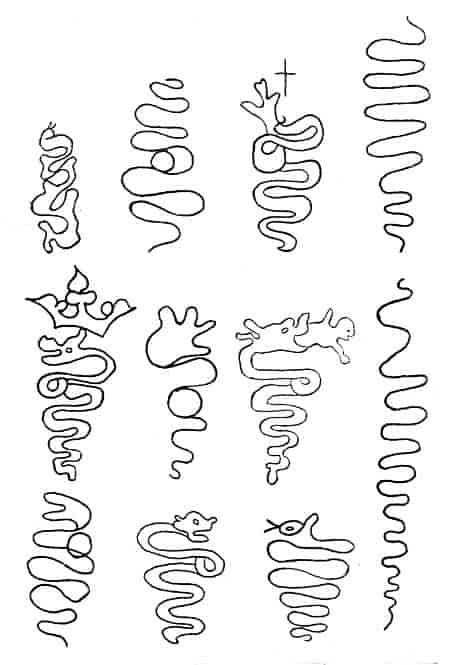

The earliest British shrines were merely stones, or caves, or holy wells, or sacred trees, or tumuli, preferably on a hill-top or in a wood. The next type is found in the monastery of St. Bride, which was simply a circular palisade encircling a sacred fire. This was in all probability similar to the earliest known form of the Egyptian temple, a wicker hut with tall poles forming the sides of the door; in front of this extended an enclosure which had two poles with flags on either side of the entrance. In the middle of the enclosure or court was a staff bearing the emblem of the God.

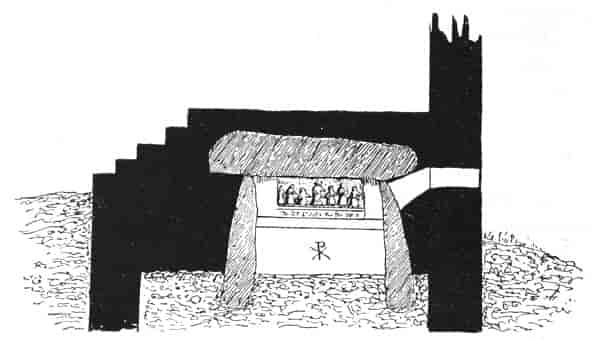

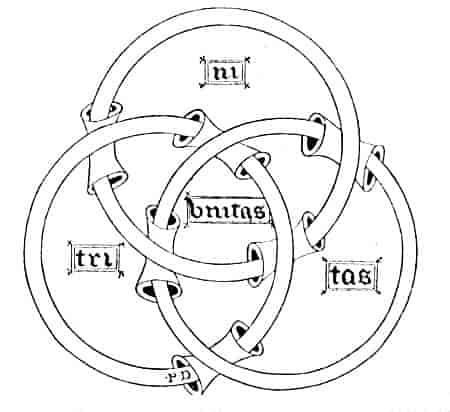

Later came stone circles and megalithic monuments in various forms, whence the connection is direct to cathedrals such as Chartres, which is said to be built largely from the remains of the prehistoric megaliths which originally stood there. There are chapels in Brittany and elsewhere built over pagan monoliths; indeed no new faith can ever do more than superimpose itself upon an older one, and statements about the wise and tender treatment of the old nature worship by the Church are euphemisms for the bald fact that Christianity, finding it impracticable to wean the heathen from their obdurate beliefs, made the best of the situation by decreeing its feasts to coincide with pre-existing festivals.

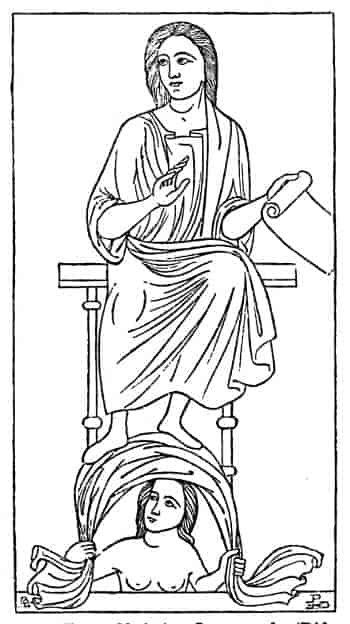

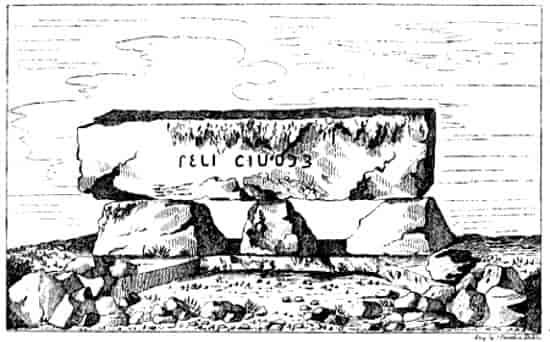

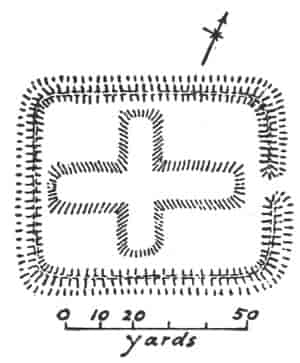

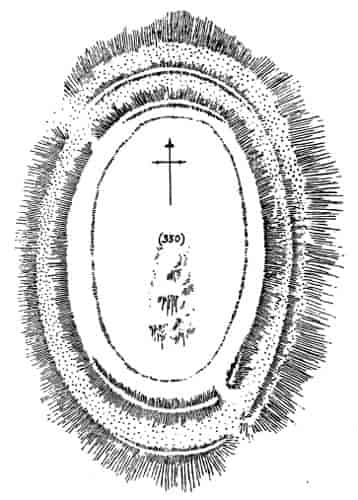

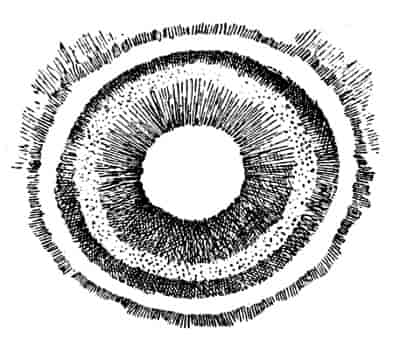

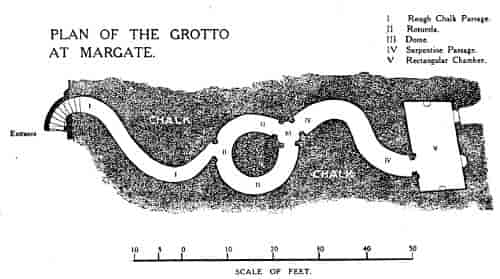

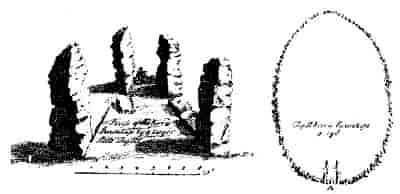

Fig. 3.—Section of the Dolmen Chapel of the Seven Sleepers near Plouaret.

It has long been generally appreciated that the lives of saints are not only for the most part mythical, but that even documentary evidence on that subject is equally suspect.[37] There is, indeed, no room to doubt that the majority of the ancient saint-stories are Christianised versions of such scraps and traditions of prehistoric mythology as had continued to linger among the folk. To the best of my belief I am the first folklorist who has endeavoured to treat The Golden Legend in a sympathetic spirit as almost pure mythology.

It is usually assumed that at any rate the Christian Church tactfully decanted the old wine of paganism into new bottles; but Christianity, as will be seen, more often did not trouble to provide even new bottles, and merely altered a stroke here and there on the labels, transforming San tan, the Holy Fire, into St. Anne, Sin clair, the Holy Light, into St. Clare, and so forth.

The first written record of Christianity in Britain is approximately A.D. 200, whence it is claimed that the Christian religion must have been introduced very near to, if not in, apostolic times. In 314 three British bishops, each accompanied by a priest and a deacon, were present at the Council at Arles, and it is commonly maintained by the Anglican Church that only a relatively small part of England owes its conversion to the Roman mission of the monk Augustine in 597.

We have it on the notable authority of St. Augustine that: “That very thing which is now designated the Christian religion was in existence among the ancients, nor was it absent even from the commencement of the human race up to the time when Christ entered into the flesh, after which true religion, which already existed, began to be called Christian”.

We should undoubtedly possess more specific evidences of the ancient faith but for the edicts of the Church that all writings adverse to the claims of the Christian religion, in the possession of whomsoever they should be found, should be committed to the fire. It is claimed for St. Patrick that he caused to be destroyed 180—some say 300—volumes relating to the Druidic system. These, said a complacent commentator, were stuffed with the fables and superstitions of heathen idolatry and unfit to be transmitted to posterity.

Mr. Westropp considers that much of value escaped destruction, for Christianity in Ireland was a tactful, warm-hearted mother, and learned the stories to tell to her children. This is true to some extent, but in Britain there are extant many bardic laments at the intolerance with which old ideas were eradicated, e.g., “Monks congregate like wolves wrangling with their instructors. They know not when the darkness and the dawn divide, nor what is the course of the wind, or the cause of its agitation; in what place it dies away or on what region it expands.” And implying that although one may be right it does not follow that all others must be wrong the same bard exclaims, “For one hour persecute me not!” and he pathetically asks: “Is there but one course to the wind, but one to the waters of the sea? Is there but one spark in the fire of boundless energy?”

In the same strain another bard, in terms not altogether inapplicable to-day, alludes to his opponents as “like little children disagreeing on the beach of the sea”.

Although bigotry and materialism have suppressed facts, stifled testimony, misrepresented witnesses, and destroyed or perverted documents, the prehistoric fairy faith was happily too deeply graven thus to be obliterated, and it is only a matter of time and study to reconstruct it. Most of the suggestions I venture to put forward are sufficiently documented by hard facts, but some are necessarily based upon “hints and equivocal survivals”.[38] At the threshold of an essay of the present character one can hardly do better than appropriate the words of Edmund Spenser:—I do gather a likelihood of truth not certainly affirming anything, but by conferring of times, language, monuments, and such like, I do hunt out a probability of things which I leave to your judgment to believe or refuse.

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Dent, 1909.

[2] The Lost Language of Symbolism: An inquiry into the origin of certain letters, words, names, fairy-tales, folklore, and mythologies. 2 vols. London, 1912 (Williams & Norgate).

[3] Manchester Guardian, 23rd December, 1912.

[4] Sonia.

[5] “Topographical comment—I will not say criticism—has been equally inefficient. A theory is not refuted by saying ‘all the great antiquarians are against you,’ ‘the Psalter of Tara refutes that,’ or ‘O’Donovan has set the question past all doubt’. These remarks only prove that we have hardly commenced scientific archæology in this country.”—;Westropp, Thos. J., Proc. of Royal Irish Acad., vol. xxxiv., C., No. 8, p. 129.

[6] We found precisely the same things as were found by our predecessors, remains of extinct animals in the cave earth, and with them flint implements in considerable numbers. You want, of course, to know how the scientific world received these latter discoveries. They simply scouted them. They told us that our statements were impossible, and we simply responded with the remark that we had not said that they were possible, only that they were true.—Pengally, W., Kent’s Cavern. Its Testimony to the Antiquity of Man, p. 12.

[7] Lubbock, J., Prehistoric Times.

[8] In the course of his criticism the same writer pertinently observes:—

“Why, what a wonderful thing is this! We have, in the first place, the most weighty and explicit testimony—Strabo’s, Cæsar’s, Lucan’s—that this race once possessed a special, profound, spiritual discipline, that they were, to use Mr. Nash’s words, ‘Wiser than their neighbours’. Lucan’s words are singularly clear and strong, and serve well to stand as a landmark in this controversy, in which one is sometimes embarrassed by hearing authorities quoted on this side or that, when one does not feel sure precisely what they say, how much or how little. Lucan, addressing those hitherto under the pressure of Rome, but now left by the Roman Civil War to their own devices, says:—

“‘Ye too, ye bards, who by your praises perpetuate the memory of the fallen brave, without hindrance poured forth your strains. And ye, ye Druids, now that the sword was removed, began once more your barbaric rites and weird solemnities. To you only is given the knowledge or ignorance (whichever it be) of the gods and the powers of heaven; your dwelling is in the lone heart of the forest. From you we learn that the bourne of man’s ghost is not the senseless grave, not the pale realm of the monarch below; in another world his spirit survives still.’”

[9] “Circles form another group of the monuments we are about to treat of.... In France they are hardly known, though in Algeria they are frequent. In Denmark and Sweden they are both numerous and important, but it is in the British Islands that circles attained their greatest development.”—;Fergusson, J., Rude Stone Monuments, p. 47. Referring to Stanton Drew the same authority observes: “Meanwhile it may be well to point out that this class of circles is peculiar to England. They do not exist in France or Algeria. The Scandinavian circles are all very different, so too are the Irish.”—Ibid., p. 153.

[10] Stevens, F., Stonehenge To-day and Yesterday, 1916, p. 14.

[11] Toland, History of the Druids, p. 163.

[12] Schrader, O., cf. Taylor, Isaac, The Origin of the Aryans, p. 48.

[13] Latham, Dr. R. G.

[14] Spain and Portugal, vol. i., p. 16.

[15] Mr. Hammer, a German who has travelled lately in Egypt and Syria, has brought, it seems, to England a manuscript written in Arabic. It contains a number of alphabets. Two of these consist entirely of trees. The book is of authority.—Davies, E., Celtic Researches, 1804, p. 305.

[16] The Cretans were rulers of the sea, and according to Thucydides King Minos of Crete was “the first person known to us in history as having established a navy. He made himself master of what is now called the Hellenic Sea, and ruled over the Cyclades, into most of which he sent his first colonists, expelling the Carians and appointing his own sons governors; and thus did his best to put down piracy in those waters.”

[17] Jones, J. J., Britannia Antiquissima, 1866.

[18] Mackenzie, D. A., Myths of Crete, p. xxix.

[19] Gray, Mrs. Hamilton, The Sepulchres of Etruria, p. 223.

[20] This might be due to the coasts being less liable to the plough. See, however, the map of distribution, published by Fergusson, in Rude Stone Monuments.

[21] Herbert, A., Cyclops Britannica, p. 68.

[22] Taliesin, p. 23.

[23] Connellan, A. F. M., p. 337.

[24] Aristotle.

[25] Smith, Worthington, G., Man the Primeval Savage, p. 53.

[26] Short History, p. 15.

[27] Bede.

[28] The cities which had been erected in considerable numbers by the Romans were sacked, burnt, and then left as ruins by the Anglo-Saxons, who appear to have been afraid or at least unwilling to use them as places of habitation. An instance of this may be found in the case of Camboritum, the important Roman city which corresponded to our modern Cambridge, which was sacked by the invaders and left a ruin at least until the time of the Venerable Bede, 673-735.—Windle, B. C. A., Life in Early Britain, p. 14.

[29] Hearnshaw, F. J. C., England in the Making, p. 14.

[30] Hawkins, E., The Silver Coins of England, p. 17.

[31] Coins of the Ancient Britons, p. 121.

[32] Bello Gallico, Bk. v., 12, § 3.

[33] Smith, Dr. Wm., Lectures on the English Language, p. 29.

[34] The Americans would describe Gildas as a “Calamity-howler”.

[35] Le Braz, A., The Night of Fires.

[36] A Cantanzaro, dans la Calabre, la cathédrale fut le théâtre de scènes de désordre extraordinaires. Le nouvel archevêque avait dernièrement manifesté l’intention de mettre un terme à certaines coutumes qu’il considérait comme entachées de paganisme. Ses instructions ayant été méprisées, il frappa d’interdit pour trois jours un édifice religieux. La population jura de se venger et, lorsque le nouvel archevêque fit son entrée dans la cathédrale, le jour de Pâques pour célébrer la grand’ messe, la foule, furieuse, manifesta bruyamment contre lui. Comme on craignait que sa personne fût l’objet de violences, le clergé le fit sortir en hâte par une porte de derrière. Les troupes durent être réquisitionnées pour faire évacuer le cathédrale.—La Dernière Heure, April, 1914.

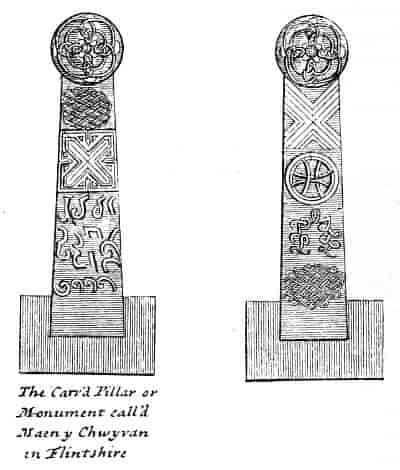

[37] There is a story told of a certain Gilbert de Stone, a fourteenth century legend-monger, who was appealed to by the monks of Holywell in Flintshire for a life of their patron saint. On being told that no materials for such a work existed the litterateur was quite unconcerned, and undertook without hesitation to compose a most excellent legend after the manner of Thomas à Becket.

[38] “Ireland being ‘the last resort of lost causes,’ preserved record of a European ‘culture’ as primitive as that of the South Seas, and therefore invaluable for the history of human advance; elsewhere its existence is only to be established from hints and equivocal survivals. Our early tales are no artificial fiction, but fragmentary beliefs of the pagan period equally valuable for topography and for mythology.”—Westropp, Thos. J., Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy, vol. xxxiv. sec. C, No. 8, p. 128.

CHAPTER II

THE MAGIC OF WORDS

“As the palimpsest of language is held up to the light and looked at more closely, it is found to be full of older forms beneath the later writing. Again and again has the most ancient speech conformed to the new grammar, until this becomes the merest surface test; it supplies only the latest likeness. Our mountains and rivers talk in the primeval mother tongue whilst the language of men is remoulded by every passing wave of change. The language of mythology and typology is almost as permanent as the names of the hills and streams.”—Gerald Massey.

It is generally admitted that place-names are more or less impervious to time and conquests. Instances seemingly without limit might be adduced of towns which have been sacked, destroyed, rebuilt, and rechristened, yet the original names—and these only—have survived. Dr. Taylor has observed that the names of five of the oldest cities of the world—Damascus, Hebron, Gaza, Sidon, and Hamath—are still pronounced in exactly the same manner as was the case thirty, or perhaps forty centuries ago, defying oftentimes the persistent attempts of rulers to substitute some other name.[39]

As another instance of the permanency of place-names, the city of Palmyra is curiously notable. Though the Greek Palmyra is a title of 2000 years’ standing, yet to the native Arab it is new-fangled, and he knows the place not as Palmyra but as Tadmor, its original and infinitely older name. Five hundred years B.C. the very ancient city of Mykenæ was destroyed and never rose again to any importance: Mykenæ was fabulously assigned to Perseus, and even to-day the stream which runs at the site is known as the Perseia.[40]

If it be possible for local names thus to live handed down humbly from mouth to mouth for thousands of years, for aught one knows they may have endured for double or treble these periods; there is no seeming limit to their vitality, and they may be said to be as imperishable and as dateless as the stones of Avebury or Stonehenge.

History knows nothing of violent and spasmodic jumps; the ideas of one era are impalpably transmitted to the next, and the continuity of custom makes it difficult to believe that the builders of Cyclopean works such as Avebury and Stonehenge, have left no imprint on our place-names, and no memories in our language. Even to-day the superstitious veneration for cromlechs and holy stones is not defunct, and it is largely due to that ingrained sentiment that more of these prehistoric monuments have not been converted into horse-troughs and pigsties.

If, as now generally admitted, there has been an unbroken and continuous village-occupation, and if, as is also now granted, our sacred places mostly occupy aboriginal and time-honoured sites, it is difficult to conceive that place-names do not preserve some traces of their prehistoric meanings. In the case of villages dedicated to some saintly man or sweetest of sweet ladies, the connection is almost certainly intact; indeed, in instances the pagan barrows in the churchyard are often actually dedicated to some saint.[41]

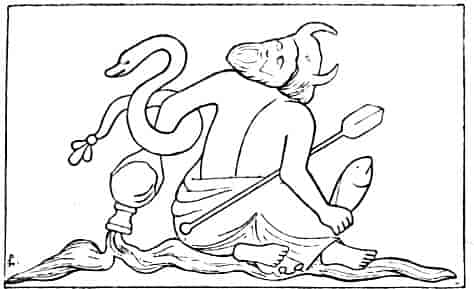

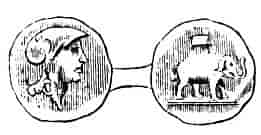

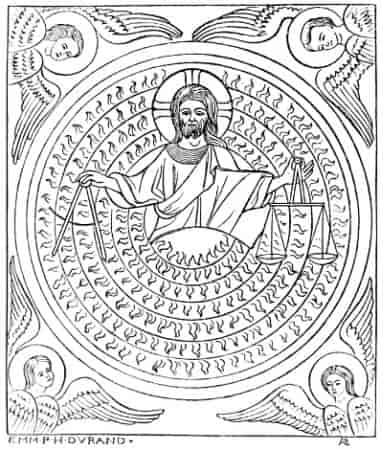

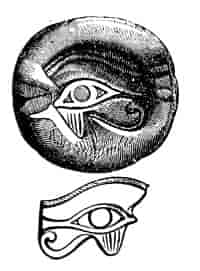

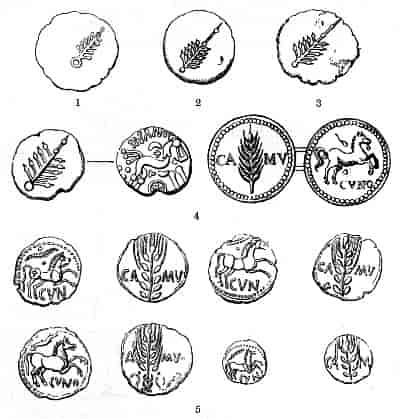

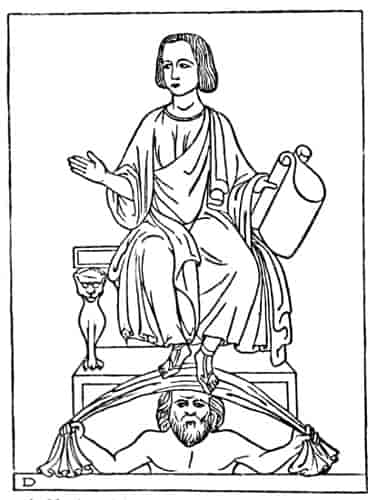

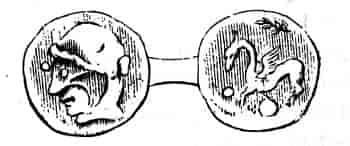

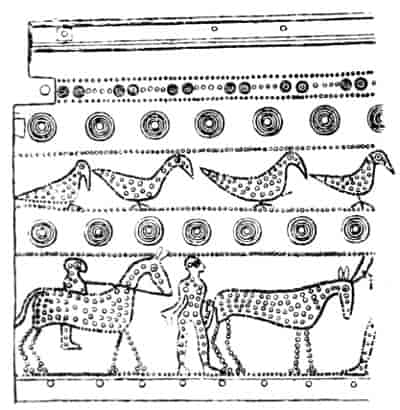

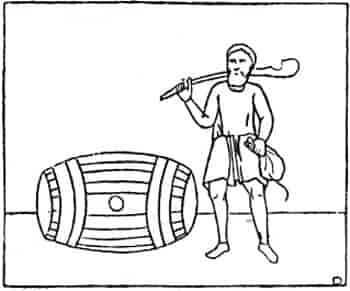

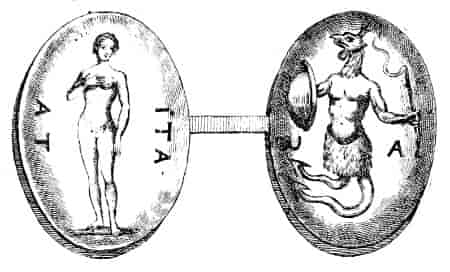

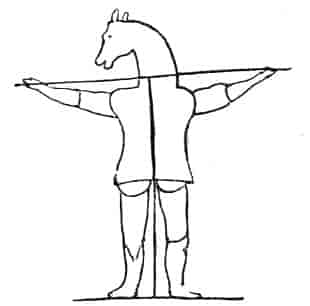

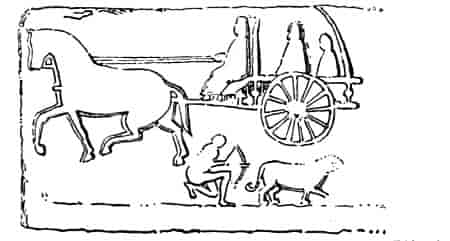

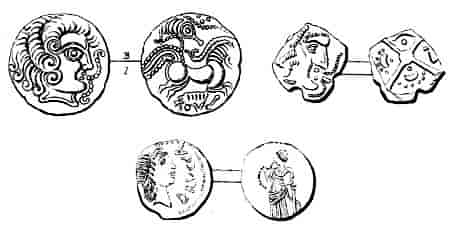

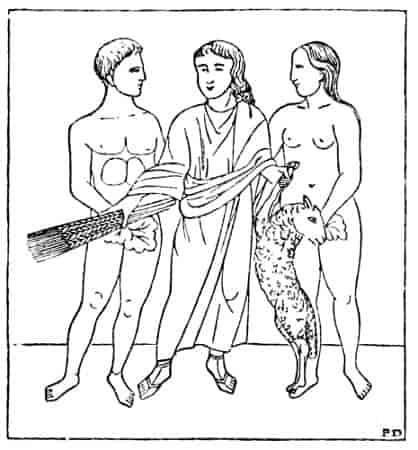

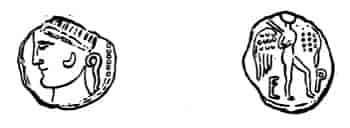

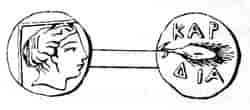

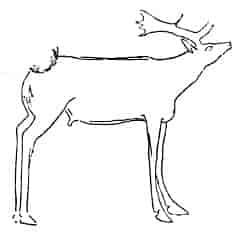

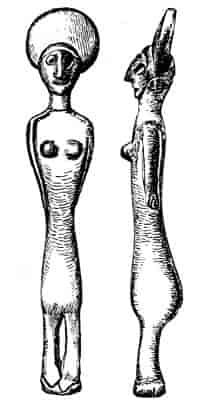

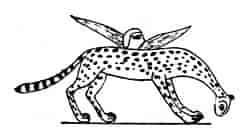

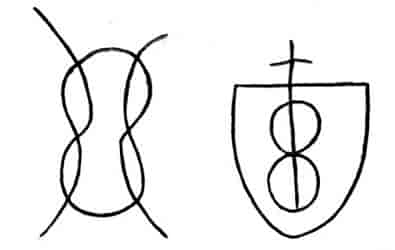

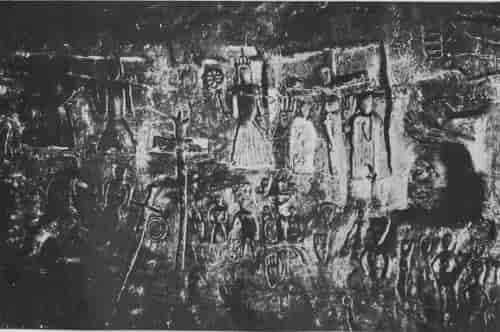

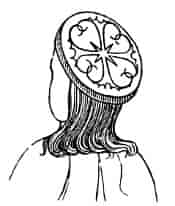

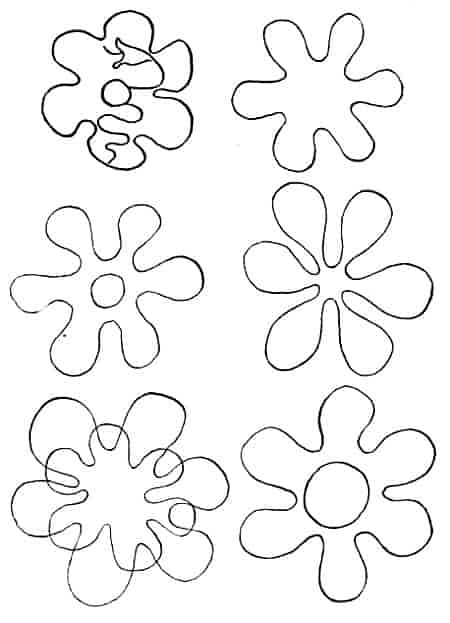

That memories of the ancient mythology sometimes hang around our British cromlechs is proved by an instance in North Wales where there still stands a table stone known locally as Llety-y-filiast, or the stone of the greyhound bitch. “This name,” says Dr. Griffith, “was given in allusion to the British Ceres or Keridwen who was symbolised by the greyhound bitch”.[42] I shall have much to say about Keridwen—“the most generous and beauteous of ladies”—meanwhile it is sufficient here to note that her symbol, the greyhound bitch, is found unmistakably upon our earliest coinage.

British.

Fig. 4.—From Evans. Fig. 5.—From Akerman.

All place-names of any real antiquity are generally composed of various languages, and like compound rocks contain fragments in juxtaposition which belong properly to different ages. The analysis of these is not difficult, as the final -hill, -ton, -ville, -ham, and so forth is usually the comparatively modern work of newcomers. Frequently the later generations forgot the original meanings of the ancient terms; and thus, for instance, at Brandon Hill in Suffolk there is the curious phenomenon of Hill Hill Hill—in three languages, i.e., bran, don, and hill. On this site the flint knappers are still at work, using practically the same rude tool as their primitive woad-painted ancestors. At Brandon not only has the art of flint-making survived, but anthropologists have noted the persistence of a swarthy and most ancient type—a persistence the more remarkable as Suffolk was supposed to be a district out of which the Britons had been wholly and irretrievably eradicated. Whether there is anything in the world to parallel the phenomenon of the Brandon flint knappers I do not know, and it may well be questioned. In the words of Dr. Rice Holmes:—The industry has been carried on since neolithic times, and even then it was ancient: for Brandon was an abode of flint makers in the Old Stone Age. Not only the pits but even the tools show little change: the picks which the modern workers use are made of iron, but here alone in Britain the old one-sided form is still retained, only the skill of the workers has degenerated: the exquisite evenness of chipping which distinguished the neolithic arrow heads is beyond the power of the most experienced knapper to reproduce.[43]

At Brandon is Broomhill; the words bran and broom will be subsequently shown to be radically the same, and I shall suggest reasons why this term, even possibly in Old Stone times, meant hill.

During recent years the study of place-names has been passing through a period of spade-work, and every available document from Doomsday Book to a Rent Roll has been scrupulously raked. The inquirer now therefore has available a remarkably interesting record of the various forms which our place-names have passed through, and he can eliminate the essential features from the non-essential. Although the subject has thus considerably been elucidated, the additional information obtained has, however, done nothing to solve the original riddle and in some cases has rendered it more complex.

The new system which is popularly supposed to have eliminated all guesswork has in reality done nothing of the kind. In place of the older method, which, in the words of Prof. Skeat, “exalted impudent assertions far above positive evidence,” it has boldly substituted a new form of guesswork which is just as reckless and in many respects is no less impudent than the old. The present fashion is to suppose that the river x or the town of y may have been the property of, or founded by, some purely hypothetical Anglo-Saxon. For example: the river Hagbourne of Berkshire is guessed to have been Hacca’s burn or brook, which possibly it was, but there is not a scintilla of real evidence one way or the other.

If one is going to postulate “Hacca’s” here and there, there is obviously a space waiting for a member of the family on the great main road entitled Akeman Street. As this ancient thoroughfare traverses Bath we are, however, told that it “received in Saxon times the significant name of Akeman Street from the condition of the gouty sufferers who travelled along it”.[44] One would prefer even a phantom Hacca to this aching man, nor does the alternatively suggested aqua, water, bring us any nearer a solution.

There sometimes appears to be no bottom to the vacuity of modern guesswork. It is seriously and not pour rire suggested that Horselydown was where horses could lie down; that Honeybrook was so designated because of its honey-sweet water, and that the name Isle of Dogs was “possibly because so many dogs were drowned in the Thames here”.[45] In what respect do these and kindred definitions, which I shall cite from standard authors of to-day, differ from the “egregious” speculations, the “wild guesses,” and the “impudent assertions” of earlier scholars?

There is in Bucks a small town now known as Kimball, anciently as Cunebal. Tradition associates this site with the British King Cymbeline or Cunobelin, and as the place further contains an eminence known as Belinsbury or Belinus Castle, the authorities can hardly avoid accepting the connection and the etymology. But for Kimbolton, which stands on a river named the Kym, the authorities—notwithstanding the river Kym—provide the purely supposititious etymology “Town of Cynebald”. There were, doubtless, thousands of Saxons whose name was Cynebald, but why Kimbolton should be assigned to any one of these hypothetical persons instead of to Cymbeline is not in any way apparent. The river name Kym is sufficient to discredit Cynebald, and the greater probability is that not only the Kym but also all our river and mountain names are pre-Saxon.

It will be seen hereafter that the name Cunobelin or Cymbeline, which the dictionaries define as meaning splendid sun, was probably adopted as a dynastic title of British chiefs, and that the effigies of Cymbeline on British coins have no more relation to any particular king than the mounted figure on our modern sovereign has to his Majesty King George V. The prefix Cym or Cuno will subsequently be seen to be the forerunner of the modern Konig or King. Hence like Kimball or Cunebal, Kimbolton on the Kym was probably a seat of a Cymbeline, and the imaginary Saxon Cynebald may be dismissed as a usurper.

Kimbolton used at one time to be known as Kinnebantum, whence it is evident that the essential part of the word is Kinne or Kim, and as another instance of the perplexing variations which are sometimes found in place-names the spot now known as Iffley may be cited. This name occurs at various periods as follows: Gifetelea, Sifetelea, Zyfteleye, Yestley, Iveclay and Iftel. This is a typical instance of the extraordinary variations which have perplexed the authorities, and is still causing them to cast vainly around for some formula or law of sound-change, which shall account satisfactorily for the problem. “We are at present,” says Prof. Wyld, “quite unable to formulate the laws of the interchange of stress in place-names, or of the effects of these in retaining, modifying, or eliminating syllables.... Until these laws are properly formulated, it cannot be said that we have a scientific account of the development of place-names. The whole thing is often little better than a conjuring trick.”[46]

No amount of brainwork has conjured any sense from Iffley, and the etymology has been placed on the shelf as “unknown”. I shall venture to suggest that the initial G, S, Z, or Y, of this name, and of many others being adjectival, the radical Ive or Iff, as being the essential, has alone survived. It will be seen that Iffley was in all probability a lea or meadow dedicated to “The Ivy Girl” or May Queen, and that quite likely it was one of the many sites where, in the language of an old poet—

I shall connote with Ivy and her maidens, not only Mother Eve, but also the clearly fabulous St. Ive. We shall see that the Lady Godiva of Coventry fame was known as Godgifu, just as Iffley was once Gifetelea, and we shall see that St. Ives in Cornwall appears in the registers alternatively as St. Yesses, just as Iffley was alternatively Yestley. Finally we shall trace the connection between Eve, the Mother of all living, and Avebury, the greatest of all megalithic monuments.

If it be objected that my method is too meticulous, and that it is impossible for mere farm- and field-names to possess any prehistoric significance, I may refer for support to the Sixth Report of the Royal Commission appointed to inventory the ancient monuments of Wales and Monmouthshire.[47] In the course of this document the Commissioners write as follows:—

“The Tithe Schedules, unsatisfactory and disappointing though many of them are, contain such a collection of place-names, principally those of fields, that the Commissioners at the outset of their inquiry determined upon a careful investigation of them. The undertaking involved in the first place the examination of hundreds of documents, many of them containing several thousands of place-names; secondly, in the case of those names which were noted for further inquiry, the necessity of discovering the position of the field or site upon the tithe map; and, thirdly, the location of the field or site on the modern six-inch ordnance sheet. This prolonged task called for much patience and care, as well as ingenuity in comparing the boundaries of eighty years ago with those of the present time.

“Of the value of this work there can be no doubt. We do not venture to express any opinion on the question whether, or to what extent, farm and field names are of service to the English archæologist; but with regard to their importance to the Welsh archæologist there can be no two opinions. The fact that the Welsh place-names are being rapidly replaced by English names, so that the local lore which is often enshrined in the former is in danger of being lost, was in itself a sufficient reason for the undertaking. The results have more than justified our decision. There is hardly a parish, certainly not one of the ancient parishes, of the principality, where the schedule of field names has not yielded some valuable results. Scores of small but in some cases important antiquities would have passed unrecorded, had it not been for the clue to their presence given by the place-name which was to be found only in the schedule to the Tithe Survey.”

In Cornwall almost every parish is named after some saintly apostle, and many of these saints are alleged to have travelled far and wide in the world founding towns and villages. It is almost a physical impossibility that this was literally true, and it becomes manifestly incredible on consideration of the miracles recorded in the lives of the travellers. As already suggested the greater probability is that the lives of the saints enshrine almost intact the traditions of pre-Christian divinities. Of the popular and most familiar St. Patrick, Borlase (W. C.), writes: “Of the reality of the existence of this Patrick, son of Calporn, we feel not the shadow of a doubt. But he was not the only Patrick, and as time went on traditions of one other Patrick at least came to be commingled with his own. We have before us the names of ten other contemporary Patricks, all ecclesiastics, and spread over Wales, Ireland, France, Spain, and Italy. The name appears to be that of a grade or order in the Church rather than a proper name in the usual sense. Thus Palladius is called also Patrick in the ‘Book of Armagh’ and the Patrick (whichever he may have been) is represented as styling Declan ‘the Patrick of the Desii,’ and Ailbhe ‘the Patrick of Munster’. When Patrick sojourned in a cave in an island in the Tyrrhene Sea he found three other Patricks there.” Precisely: and there is little doubt that our London Battersea or Patrixeye was originally an ea or island where the patricks or padres of St. Peter’s at Westminster once congregated.

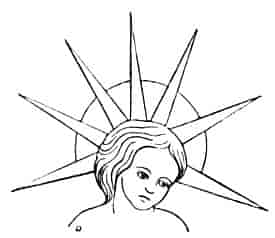

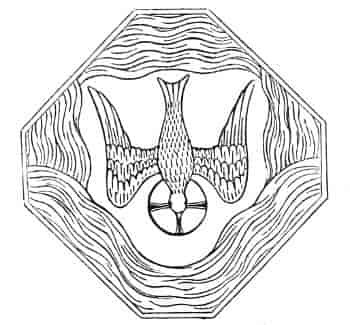

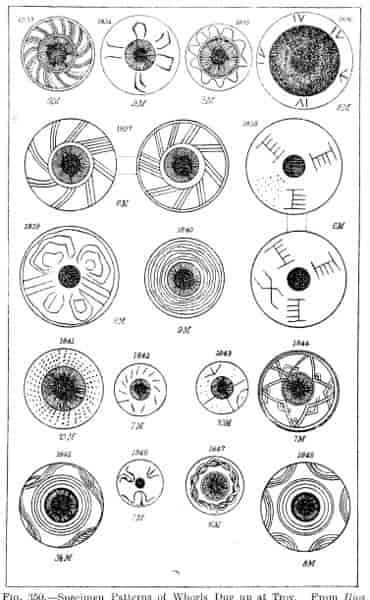

The arguments applied to St. Patrick apply equally to, say, St. Columba, or the Holy Dove, and similarly to St. Colman, a name also meaning Dove. In Ireland alone there are 200 dedications to St. Colman, and evidence will be brought forward that the archetype of all the St. Colmans and all the St. Columbas and all the Patricks was Peter the Pater, who was symbolised by petra, the stone or rock.

The so-called Ossianic poems of Gaeldom, although of “a remarkably heathenish character,” preserve the manners of and opinions of what the authorities describe as “a semi-barbarous people who were endowed with strong imagination, high courage, childlike tenderness, and gentle chivalry for women,”[48] and that the ancients were tinctured through and through with mysticism and imagination, finding tongues in trees, books in the running brooks, sermons in stones, and good in everything, is a fact which can be denied. When our words were framed and our ancient places, hills, and rivers named, I am persuaded that the world was in its imaginative childhood, and hence that traces of that state of mind may reasonably be anticipated. It is remarkable that the skulls found in the first or oldest Troy exhibit the most intellectual characteristics,[49] and in many quarters seemingly the remoter the times the purer was the theology whether in Phrygia, Egypt, India, Persia, or Great Britain. Among the Cretans “religion entered at every turn” of their social system; in Egypt even the very games and dances had a religious significance, and the evidence of folklore testifies to the same effect in Britain. It was one among the many grievances of the pessimistic Gildas that the British were “slaves to the shadows of things to come,” and this usually overlooked aspect of their character must, I think, be recognised in relation to their place-names. To a large degree the mystical element still persists in Brittany, where even to-day, in the words of Baring-Gould:—At a Pardon one sees and marvels at the wondrous faces of this remarkable people: the pure, sweet, and modest countenances of the girls, and those not less striking of the old folk. “It is,” says Durtal, “the soul which is everything in these people, and their physiognomy is modelled by it. There are holy brightnesses in their eyes, on their lips, those doors to the borders of which the soul alone can come, from which it looks forth and all but shows itself. Goodness, kindness, as well as a cloistral spirituality, stream from their faces.”[50]

What is still true of Brittany was once equally true of Britain, and although the individuality of the Gael has now largely been submerged by prosaic Anglo-Saxondom, the poetic temperament of the chivalrous and dreamy Celt was essentially a frame of mind that cared only for the heroic, the romantic, and the beautiful.

The science of etymology as practised to-day is unfortunately blind to this poetic element which was, and to some extent still is, an innate characteristic of “uncivilised” and unsophisticated peoples. Archbishop Trench, one of the original planners and promoters of The New English Dictionary, was not overstating when he wrote: “Let us then acknowledge man a born poet.... Despite his utmost efforts, were he mad enough to employ them, he could not succeed in exhausting his language of the poetical element which is inherent in it, in stripping it of blossom, flower, and fruit, and leaving it nothing but a bare and naked stem. He may fancy for a moment that he has succeeded in doing this, but it will only need for him to become a little better philologer to go a little deeper into the study of the words which he is using, and he will discover that he is as remote from this consummation as ever.”

Nevertheless, current etymology has achieved this inanity, and has so completely dismissed the animate or poetic element from its considerations that one may seek vainly the columns of Skeat and Murray for any hint or suggestion that language and imagination ever had anything in common. According to modern teaching language is a mere cluster of barbaric yawps: “No mystic bond linked word and thought together; utility and convenience alone joined them”.[51]

Words, nevertheless, were originally born not from grammarians but amid the common people, and pace Mr. Clodd they enshrine in many instances the mysticism and the superstitions of the peasantry. How can one account, for instance, for the Greek word psyche, meaning butterfly, and also soul, except by the knowledge that butterflies were regarded by the ancients as creatures into which the soul was metamorphosised? According to Grimm, the German name for stork means literally child-, or soul-bringer; hence the belief that the advent of infants was presided over by this bird. But why “hence”? and why put the cart before the horse? If one may judge from innumerable parallels of word-equivocation the legends arose not from the accident of similar words, nor from “misprision of terms,” or from any other “disease of language,” but the creatures were named because of the attendant legend. It is common knowledge that in Egypt the animal sacred to a divinity was often designated by the name of that deity; similarly in Europe the bee, a symbol of the goddess Mylitta, was called a mylitta, and a bull, the symbol of the god Thor, was named a thor. We speak to-day of an Adonis, because Adonis was a fabulously lovely youth, and parallel examples may be found on almost every hand. Irish mythology tells of a certain golden-haired hero named Bress, which means beautiful, whence we are further told that every beautiful thing in Ireland whether plain, fortress, or ale, or torch, or woman, or man, was compared with him, so that men said of them “That is a Bress”. Elsewhere and herein I have endeavoured to prove that this principle was of worldwide application, and that it is an etymological key which will open the meaning of many words still in common use. It is a correlative fact that the names of specific deities such as Horus, Hathor, Nina, Bel, etc., developed in course of time into generic terms for any Lord or God.

Very much the same principles are at work with us to-day, whence a dreadnought from the prime “Dreadnought,” and the etymologer of the future, who tries by strictly scientific methods to unravel the meaning of such words as mackintosh, brougham, Sam Browne, gladstone, boycott, etc., will find it necessary to investigate the legends attendant on those names rather than practice a formal permutation of vowels and consonants.

By common consent the quintessence of the last fifty years’ philological progress is being distilled into Sir James Murray’s New English Dictionary, and in a conciser form the same data may be found in Prof. Skeat’s Concise Etymological Dictionary of the English Language. Both these indispensable works are high watermarks of English scholarship, and whatever absurdities they contain are shortcomings not of their compilers but of the Teutonic school of philology which they exemplify. If these two standard dictionaries were able to answer even the elementary questions that are put to them it would be both idle and presumptuous to cavil, but one has only to refer to their pages to realise the ignorance which prevails as to the origin and the meaning of the most simple and everyday words.