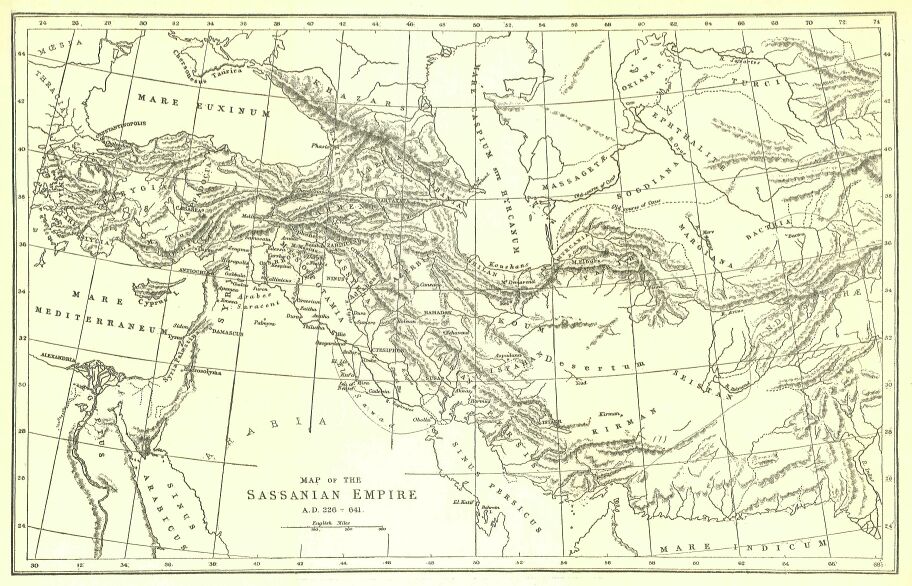

.

THE SEVEN GREAT MONARCHIES

CHAPTERS I. to XIV.

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations

CHAPTERS I. TO XIV.

WITH MAPS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

CHAPTER I.

Condition of the Persians under the Successors of Alexander—under the Arsacidce. Favor shown them by the latter—allowed to have Kings of their own. Their Religion at first held in honor. Power of their Priests. Gradual Change of Policy on the part of the Parthian Monarchs, and final Oppression of the Magi. Causes which produced the Insurrection of Artaxerxes.

"The Parthians had been barbarians; they had ruled over a nation far more civilized than themselves, and had oppressed them and their religion."

Niebuhr, Lectures on Roman History, vol. iii. p. 270.

When the great Empire of the Persians, founded by Cyrus, collapsed under the attack of Alexander the Great, the dominant race of Western Asia did not feel itself at the first reduced to an intolerable condition. It was the benevolent design of Alexander to fuse into one the two leading peoples of Europe and Asia, and to establish himself at the head of a Perso-Hellenic State, the capital of which was to have been Babylon. Had this idea been carried out, the Persians would, it is evident, have lost but little by their subjugation. Placed on a par with the Greeks, united with them in marriage bonds, and equally favored by their common ruler, they could scarcely have uttered a murmur, or have been seriously discontented with their position. But when the successors of the great Macedonian, unable to rise to the height of his grand conception, took lower ground, and, giving up the idea of a fusion, fell back upon the ordinary status, and proceeded to enact the ordinary role, of conquerors, the feelings of the late lords of Asia, the countrymen of Cyrus and Darius, must have undergone a complete change. It had been the intention of Alexander to conciliate and elevate the leading Asiatics by uniting them with the Macedonians and the Greeks, by promoting social intercourse between the two classes of his subjects and encouraging them to intermarry, by opening his court to Asiatics, by educating then in Greek ideas and in Greek schools, by promoting them to high employments, and making them feel that they were as much valued and as well cared for as the people of the conquering race: it was the plan of the Seleucidae to govern wholly by means of European officials, Greek or Macedonian, and to regard and treat the entire mass of their Asiatic subjects as mere slaves. Alexander had placed Persian satraps over most of the provinces, attaching to them Greek or Macedonian commandants as checks. Seloucus divided his empire into seventy-two satrapies; but among his satraps not one was an Asiatic—all were either Macedonians or Greeks. Asiatics, indeed, formed the bulk of his standing army, and so far were admitted to employment; they might also, no doubt, be tax-gatherers, couriers, scribes, constables, and officials of that mean stamp; but they were as carefully excluded from all honorable and lucrative offices as the natives of Hindustan under the rule of the East India Company. The standing army of the Seleucidae was wholly officered, just as was that of our own Sepoys, by Europeans; Europeans thronged the court, and filled every important post under the government. There cannot be a doubt that such a high-spirited and indeed arrogant people as the Persians must have fretted and chafed under this treatment, and have detested the nation and dynasty which had thrust them down from their pre-eminence and converted them from masters into slaves. It would scarcely much tend to mitigate the painfulness of their feelings that they could not but confess their conquerors to be a civilized people—as civilized, perhaps more civilized than themselves—since the civilization was of a type and character which did not please them or command their approval. There is an essential antagonism between European and Asiatic ideas and modes of thought, such as seemingly to preclude the possibility of Asiatics appreciating a European civilization. The Persians must have felt towards the Greco-Macedonians much as the Mohammedans of India feel towards ourselves—they may have feared and even respected them—but they must have very bitterly hated them. Nor was the rule of the Seleucidae such as to overcome by its justice or its wisdom the original antipathy of the dispossessed lords of Asia towards those by whom they had been ousted. The satrapial system, which these monarchs lazily adopted from their predecessors, the Achaemenians, is one always open to great abuses, and needs the strictest superintendence and supervision. There is no reason to believe that any sufficient watch was kept over their satraps by the Seleucid kings, or even any system of checks established, such as the Achaemenidae had, at least in theory, set up and maintained. The Greco-Macedonian governors of provinces seem to have been left to themselves almost entirely, and to have been only controlled in the exercise of their authority by their own notions of what was right or expedient. Under these circumstances, abuses were sure to creep in; and it is not improbable that gross outrages were sometimes perpetrated by those in power—outrages calculated to make the blood of a nation boil, and to produce a keen longing for vengeance. We have no direct evidence that the Persians of the time did actually suffer from such a misuse of satrapial authority; but it is unlikely that they entirely escaped the miseries which are incidental to the system in question. Public opinion ascribed the grossest acts of tyranny and oppression to some of the Seleucid satraps; probably the Persians were not exempt from the common lot of the subject races.

Moreover, the Seleucid monarchs themselves were occasionally guilty of acts of tyranny, which must have intensified the dislike wherewith they were regarded by their Asiatic subjects. The reckless conduct of Antiochus Epiphanes towards the Jews is well known; but it is not perhaps generally recognized that intolerance and impious cupidity formed a portion of the system on which he governed. There seems, however, to be good reason to believe that, having exhausted his treasury by his wars and his extravagances, Epiphanes formed a general design of recruiting it by means of the plunder of his subjects. The temples of the Asiatics had hitherto been for the most part respected by their European conquerors, and large stores of the precious metals were accumulated in them. Epiphanes saw in these hoards the means of relieving his own necessities, and determined to seize and confiscate them. Besides plundering the Temple of Jehovah at Jerusalem, he made a journey into the southeastern portion of his empire, about B.C. 165, for the express purpose of conducting in person the collection of the sacred treasures. It was while he was engaged in this unpopular work that a spirit of disaffection showed itself; the East took arms no less than the West; and in Persia, or upon its borders, the avaricious monarch was forced to retire before the opposition which his ill-judged measures had provoked, and to allow one of the doomed temples to escape him. When he soon afterwards sickened and died, the natives of this part of Asia saw in his death a judgment upon him for his attempted sacrilege.

It was within twenty years of this unfortunate attempt that the dominion of the Seleucidae over Persia and the adjacent countries came to an end. The Parthian Empire had for nearly a century been gradually growing in power and extending itself at the expense of the Syro-Macedonian; and, about B.C. 163, an energetic prince, Mithridates I., commenced a series of conquests towards the West, which terminated (about B.C. 150) in the transference from the Syro-Macedonian to the Parthian rule of Media Magna, Susiana, Persia, Babylonia, and Assyria Proper. It would seem that the Persians offered no resistance to the progress of the new conqueror. The Seleucidae had not tried to conciliate their attachment, and it was impossible that they should dislike the rupture of ties which had only galled hitherto. Perhaps their feeling, in prospect of the change, was one of simple indifference. Perhaps it was not without some stir of satisfaction and complacency that they saw the pride of the hated Europeans abased, and a race, which, however much it might differ from their own, was at least Asiatic, installed in power. The Parthia system, moreover, was one which allowed greater liberty to the subject races than the Macedonian, as it had been understood and carried out by the Seleucidae; and so far some real gain was to be expected from the change. Religious motives must also have conspired to make the Persians sympathize with the new power, rather than with that which for centuries had despised their faith and had recently insulted it.

The treatment of the Persians by their Parthian lords seems, on the whole, to have been marked by moderation. Mithridates indeed, the original conqueror, is accused of having alienated his new subjects by the harshness of his rule; and in the struggle which occurred between him and the Seleucid king, Demetrius II., Persians, as well as Elymseans and Bactrians, are said to have fought on the side of the Syro-Macedonian. But this is the only occasion in Parthian history, between the submission of Persia and the great revolt under Artaxerxes, where there is any appearance of the Persians regarding their masters with hostile feelings. In general they show themselves submissive and contented with their position, which was certainly, on the whole, a less irksome one than they had occupied under the Seleucidae.

It was a principle of the Parthian governmental system to allow the subject peoples, to a large extent, to govern themselves. These peoples generally, and notably the Persians, were ruled by native kings, who succeeded to the throne by hereditary right, had the full power of life and death, and ruled very much as they pleased, so long as they paid regularly the tribute imposed upon them by the "King of Kings," and sent him a respectable contingent when he was about to engage in a military expedition. Such a system implies that the conquered peoples have the enjoyment of their own laws and institutions, are exempt from troublesome interference, and possess a sort of semi-independence. Oriental nations, having once assumed this position, are usually contented with it, and rarely make any effort to better themselves. It would seem that, thus far at any rate, the Persians could not complain of the Parthian rule, but must have been fairly satisfied with their condition.

Again, the Greco-Macedonians had tolerated, but they had not viewed with much respect, the religion which they had found established in Persia. Alexander, indeed, with the enlightened curiosity which characterised him, had made inquiries concerning, the tenets of the Magi, and endeavored to collect in one the writings of Zoroaster. But the later monarchs, and still more their subjects, had held the system in contempt, and, as we have seen, Epiphanes had openly insulted the religious feelings of his Asiatic subjects. The Parthians, on the other hand, began at any rate with a treatment of the Persian religion which was respectful and gratifying. Though perhaps at no time very sincere Zoroastrians, they had conformed to the State religion under the Achaemenian kings; and when the period came that they had themselves to establish a system of government, they gave to the Magian hierarchy a distinct and important place in their governmental machinery. The council, which advised the monarch, and which helped to elect and (if need were) depose him, was composed of two elements—-the Sophi, or wise men, who were civilians; and the Magi, or priests of the Zoroastrian religion. The Magi had thus an important political status in Parthia, during the early period of the Empire; but they seem gradually to have declined in favor, and ultimately to have fallen into disrepute. The Zoroastrian creed was, little by little, superseded among the Parthians by a complex idolatry, which, beginning with an image-worship of the Sun and Moon, proceeded to an association with those deities of the deceased kings of the nation, and finally added to both a worship of ancestral idols, which formed the most cherished possession of each family, and practically monopolized the religious sentiment. All the old Zoroastrian practices were by degrees laid aside. In Armenia the Arsacid monarchs allowed the sacred fire of Ormazd to become extinguished; and in their own territories the Parthian Arsacidae introduced the practice, hateful to Zoroastrians, of burning the dead. The ultimate religion of these monarchs seems in fact to have been a syncretism wherein Sabaism, Confucianism, Greco-Macedonian notions, and an inveterate primitive idolatry were mixed together. It is not impossible that the very names of Ormazd and Ahriman had ceased to be known at the Parthian Court, or were regarded as those of exploded deities, whose dominion over men's minds had passed away.

On the other hand, in Persia itself, and to some extent doubtless among the neighboring countries, Zoroastrianism (or what went by the name) had a firm hold on the religious sentiments of the multitude, who viewed with disfavor the tolerant and eclectic spirit which animated the Court of Ctesiphon. The perpetual fire, kindled, as it was, from heaven, was carefully tended and preserved on the fire-altars of the Persian holy places; the Magian hierarchy was held in the highest repute, the kings themselves (as it would seem) not disdaining to be Magi; the ideas—even perhaps the forms—of Ormazd and Ahriman were familiar to all; image-worship was abhorred the sacred writings in the Zend or most ancient Iranian language were diligently preserved and multiplied; a pompous ritual was kept up; the old national religion, the religion of the Achaemenians, of the glorious period of Persian ascendency in Asia, was with the utmost strictness maintained, probably the more zealously as it fell more and more into disfavor with the Parthians.

The consequence of this divergence of religious opinion between the Persians and their feudal lords must undoubtedly have been a certain amount of alienation and discontent. The Persian Magi must have been especially dissatisfied with the position of their brethren at Court; and they would doubtless use their influence to arouse the indignation of their countrymen generally. But it is scarcely probable that this cause alone would have produced any striking result. Religious sympathy rarely leads men to engage in important wars, unless it has the support of other concurrent motives. To account for the revolt of the Persians against their Parthian lords under Artaxerxes, something more is needed than the consideration of the religious differences which separated the two peoples.

First, then, it should be borne in mind that the Parthian rule must have been from the beginning distasteful to the Persians, owing to the rude and coarse character of the people. At the moment of Mithridates's successes, the Persians might experience a sentiment of satisfaction that the European invader was at last thrust back, and that Asia had re-asserted herself; but a very little experience of Parthian rule was sufficient to call forth different feelings. There can be no doubt that the Parthians, whether they were actually Turanians or no, were, in comparison with the Persians, unpolished and uncivilized. They showed their own sense of this inferiority by an affectation of Persian manners. But this affectation was not very successful. It is evident that in art, in architecture, in manners, in habits of life, the Parthian race reached only a low standard; they stood to their Hellenic and Iranian subjects in much the same relation that the Turks of the present day stand to the modern Greeks; they made themselves respected by their strength and their talent for organization; but in all that adorns and beautifies life they were deficient. The Persians must, during the whole time of their subjection to Parthia, have been sensible of a feeling of shame at the want of refinement and of a high type of civilization in their masters.

Again, the later sovereigns of the Arsacid dynasty were for the most part of weak and contemptible character. From the time of Volagases I. to that of Artabanus IV., the last king, the military reputation of Parthia had declined. Foreign enemies ravaged the territories of Parthian vassal kings, and retired when they chose, unpunished. Provinces revolted and established their independence. Rome was entreated to lend assistance to her distressed and afflicted rival, and met the entreaties with a refusal. In the wars which still from time to time were waged between the two empires Parthia was almost uniformly worsted. Three times her capital was occupied, and once her monarch's summer palace was burned. Province after province had to be ceded to Rome. The golden throne which symbolized her glory and magnificence was carried off. Meanwhile feuds raged between the different branches of the Arsacid family; civil wars were frequent; two or three monarchs at a time claimed the throne, or actually ruled in different portions of the Empire. It is not surprising that under these circumstances the bonds were loosened between Parthia and her vassal kingdoms, or that the Persian tributary monarchs began to despise their suzerains, and to contemplate without alarm the prospect of a rebellion which should place them in an independent position.

While the general weakness of the Arsacid monarchs was thus a cause naturally leading to a renunciation of their allegiance on the part of the Persians, a special influence upon the decision taken by Artaxerxes is probably to be assigned to one, in particular, of the results of that weakness. When provinces long subject to Parthian rule revolted, and revolted successfully, as seems to have been the case with Hyrcania, and partially with Bactria, Persia could scarcely for very shame continue submissive. Of all the races subject to Parthia, the Persians were the one which had held the most brilliant position in the past, and which retained the liveliest remembrance of its ancient glories. This is evidenced not only by the grand claims which Artaxorxes put forward in his early negotiations with the Romans, but by the whole course of Persian literature, which has fundamentally an historic character, and exhibits the people as attached, almost more than any other Oriental nation, to the memory of its great men and of their noble achievements. The countrymen of Cyrus, of Darius, of Xerxes, of Ochus, of the conquerors of Media, Bactria, Babylon, Syria, Asia Minor, Egypt, of the invaders of Scythia and Greece, aware that they had once borne sway over the whole region between Tunis and the Indian Desert, between the Caucasus and the Cataracts, when they saw a petty mountain clan, like the Hyrcanians, establish and maintain their independence despite the efforts of Parthia to coerce them, could not very well remain quiet. If so weak and small a race could defy the power of the Arsacid monarchs, much more might the far more numerous and at least equally courageous Persians expect to succeed, if they made a resolute attempt to recover their freedom.

It is probable that Artaxerxes, in his capacity of vassal, served personally in the army with which the Parthian monarch Artabanus carried on the struggle against Rome, and thus acquired the power of estimating correctly the military strength still possessed by the Arsacidae, and of measuring it against that which he knew to belong to his nation. It is not unlikely that he formed his plans during the earlier period of Artabanus's reign, when that monarch allowed himself to be imposed upon by Caracallus, and suffered calamities and indignities in consequence of his folly. When the Parthian monarch atoned for his indiscretion and wiped out the memory of his disgraces by the brilliant victory of Nisibis and the glorious peace which he made with Macrinus, Artaxerxes may have found that he had gone too far to recede; or, undazzled by the splendor of these successes, he may still have judged that he might with prudence persevere in his enterprise. Artabanus had suffered great losses in his two campaigns against Rome, and especially in the three days' battle of Nisibis. He was at variance with several princes of his family, one of whom certainly maintained himself during his whole reign with the State and title of "King of Parthia." Though he had fought well at Nisibis, he had not given any indications of remarkable military talent. Artaxerxes, having taken the measure of his antagonist during the course of the Roman war, having estimated his resources and formed a decided opinion on the relative strength of Persia and Parthia, deliberately resolved, a few years after the Roman war had come to an end, to revolt and accept the consequences. He was no doubt convinced that his nation would throw itself enthusiastically into the struggle, and he believed that he could conduct it to a successful issue. He felt himself the champion of a depressed, if not an oppressed, nationality, and had faith in his power to raise it into a lofty position. Iran, at any rate, should no longer, he resolved, submit patiently to be the slave of Turan; the keen, intelligent, art-loving Aryan people should no longer bear submissively the yoke of the rude, coarse, clumsy Scyths. An effort after freedom should be made. He had little doubt of the result. The Persians, by the strength of their own right arms and the blessing of Ahuramazda, the "All-bounteous," would triumph over their impious masters, and become once more a great and independent people. At the worst, if he had miscalculated, there would be the alternative of a glorious death upon the battle-field in one of the noblest of all causes, the assertion of a nation's freedom.

CHAPTER II.

Situation and Size of Persia. General Character of the Country and Climate. Chief Products. Characteristics of the Persian People, physical and moral. Differences observable in the Race at different periods.

Persia Proper was a tract of country lying on the Gulf to which it has given name, and extending about 450 miles from north-west to south-east, with an average breadth of about 250 miles. Its entire area may be estimated at about a hundred thousand square miles. It was thus larger than Great Britain, about the size of Italy, and rather less than half the size of France. The boundaries were, on the west, Elymais or Susiana (which, however, was sometimes reckoned a part of Persia); on the north, Media; on the east, Carmania; and on the south, the sea. It is nearly represented in modern times by the two Persian provinces of Farsistan and Laristan, the former of which retains, but slightly changed, the ancient appellation. The Hindyan or Tab (ancient Oroatis) seems towards its mouth to have formed the western limit. Eastward, Persia extended to about the site of the modern Bunder Kongo. Inland, the northern boundary ran probably a little south of the thirty-second parallel, from long. 50° to 55°. The line dividing Persia Proper from Carmania (now Kerman) was somewhat uncertain.

The character of the tract is extremely diversified. Ancient writers divided the country into three strongly contrasted regions. The first, or coast tract, was (they said) a sandy desert, producing nothing but a few dates, owing to the intensity of the heat. Above this was a fertile region, grassy, with well-watered meadows and numerous vineyards, enjoying a delicious climate, producing almost every fruit but the olive, containing pleasant parks or "paradises," watered by a number of limpid streams and clear lakes, well wooded in places, affording an excellent pasture for horses and for all sorts of cattle, abounding in water-fowl and game of every kind, and altogether a most delightful abode. Beyond this fertile region, towards the north, was a rugged mountain tract, cold and mostly covered with snow, of which they did not profess to know much.

In this description there is no doubt a certain amount of truth; but it is mixed probably with a good deal of exaggeration. There is no reason to believe that the climate or character of the country has undergone any important alteration between the time of Nearchus or Strabo and the present day. At present it is certain that the tract in question answers but very incompletely to the description which those writers give of it. Three regions may indeed be distinguished, though the natives seem now to speak of only two; but none of them corresponds at all exactly to the accounts of the Greeks. The coast tract is represented with the nearest approach to correctness. This is, in fact, a region of arid plain, often impregnated with salt, ill-watered, with a poor soil, consisting either of sand or clay, and productive of little besides dates and a few other fruits. A modern historian says of it that "it bears a greater resemblance in soil and climate to Arabia than to the rest of Persia." It is very hot and unhealthy, and can at no time have supported more than a sparse and scanty population. Above this, towards the north, is the best and most fertile portion of the territory. A mountain tract, the continuation of Zagros, succeeds to the flat and sandy coast region, occupying the greater portion of Persia Proper. It is about two hundred miles in width, and consists of an alternation of mountain, plain, and narrow valley, curiously intermixed, and hitherto mapped very imperfectly. In places this district answers fully to the description of Nearchus, being, "richly fertile, picturesque, and romantic almost beyond imagination, with lovely wooded dells, green mountain sides, and broad plains, suited for the production of almost any crops." But it is only to the smaller moiety of the region that such a character attaches; more than half the mountain tract is sterile and barren; the supply of water is almost everywhere scanty; the rivers are few, and have not much volume; many of them, after short courses, end in the sand, or in small salt lakes, from which the superfluous water is evaporated. Much of the country is absolutely without streams, and would be uninhabitable were it not for the kanats or kareezes—subterranean channels made by art for the conveyance of spring water to be used in irrigation. The most desolate portion of the mountain tract is towards the north and north-east, where it adjoins upon the third region, which is the worst of the three. This is a portion of the high tableland of Iran, the great desert which stretches from the eastern skirts of Zagros to the Hamoon, the Helmend, and the river of Subzawur. It is a dry and hard plain, intersected at intervals by ranges of rocky hills, with a climate extremely hot in summer and extremely cold in winter, incapable of cultivation, excepting so far as water can be conveyed by kanats, which is, of course, only a short distance. The fox, the jackal, the antelope, and the wild ass possess this sterile and desolate tract, where "all is dry and cheerless," and verdure is almost unknown.

Perhaps the two most peculiar districts of. Persia are the lake basins of Neyriz and Deriah-i-Nemek. The rivers given off from the northern side of the great mountain chain between the twenty-ninth and thirty-first parallels, being unable to penetrate the mountains, flow eastward towards the desert; and their waters gradually collect into two streams, which end in two lakes, the Deriah-i-Nemek and that of Neyriz, or Lake Bakhtigan. The basin of Lake Neyriz lies towards the north. Here the famous Bendamir, and the Pulwar or Kur-ab, flowing respectively from the north-east and the north, unite in one near the ruins of the ancient Persepolis, and, after fertilizing the plain of Merdasht, run eastward down a rich vale for a distance of some forty miles into the salt lake which swallows them up. This lake, when full, has a length of fifty or sixty miles, with a breadth of from three to six. In summer, however, it is often quite dry, the water of the Bendamir being expended in irrigation before reaching its natural terminus. The valley and plain of the Bendamir, and its tributaries, are among the most fertile portions of Persia, as well as among those of most historic interest.

The basin of the Deriah-i-Nemek is smaller than that of the Neyriz, but it is even more productive. Numerous brooks and streams, rising not far from Shiraz, run on all sides into the Nemek lake, which has a length of about fifteen and a breadth of three or three and a half miles. Among the streams is the celebrated brook of Hafiz, the Rocknabad, which still retains "its singular transparency and softness to the taste." Other rills and fountains of extreme clearness abound, and a verdure is the result, very unusual in Persia. The vines grown in the basin produce the famous Shiraz wine, the only good wine which is manufactured in the East. The orchards are magnificent. In the autumn "the earth is covered with the gathered harvest, flowers, and fruits; melons, peaches, pears, nectarines, cherries, grapes, pomegranates; all is a garden, abundant in sweets and refreshment."

But, notwithstanding the exceptional fertility of the Shiraz plain and of a few other places, Persia Proper seems to have been rightly characterized in ancient times as "a scant land and a rugged." Its area was less than a fifth of the area of modern Persia; and of this space nearly one half was uninhabitable, consisting either of barren stony mountain or of scorching sandy plain, ill supplied with water and often impregnated with salt. Its products, consequently, can have been at no time either very abundant or very varied. Anciently, the low coast tract seems to have been cultivated to a small extent in corn, and to have produced good dates and a few other fruits. The mountain region was, as we have seen, celebrated for its excellent pastures, for its abundant fruits, and especially for its grapes. Within the mountains, on the high plateau, assafoetida (silphium) was found, and probably some other medicinal herbs. Corn, no doubt, could be grown largely in the plains and valleys of the mountain tract, as well as on the plateau, so far as the kanats carried the water. There must have been, on the whole, a deficiency of timber, though the palms of the low tract, and the oaks, planes, chenars or sycamores, poplars, and willows of the mountain regions sufficed for the wants of the natives. Not much fuel was required, and stone was the general material used for building. Among the fruits for which Persia was famous are especially noted the peach, the walnut, and the citron. The walnut bore among the Romans the appellation of "royal."

Persia, like Media, was a good nursery for horses. Fine grazing grounds existed in many parts of the mountain region, and for horses of the Arab breed even the Deshtistan was not unsuited. Camels were reared in some places, and sheep and goats were numerous. Horned cattle were probably not so abundant, as the character of the country is not favorable for them. Game existed in large quantities, the lakes abounding with water-fowl, such as ducks, teal, heron, snipe, etc.; and the wooded portions of the mountain tract giving shelter to the stag, the wild goat, the wild boar, the hare, the pheasant, and the heathcock, fish were also plentiful. Whales visited the Persian Gulf, and were sometimes stranded upon the shores, where their carcases furnished a mine of wealth to the inhabitants. Dolphins abounded, as well as many smaller kinds; and shell-fish, particularly oysters, could always be obtained without difficulty. The rivers, too, were capable of furnishing fresh-water fish in good quantity, though we cannot say if this source of supply was utilized in antiquity.

The mineral treasures of Persia were fairly numerous. Good salt was yielded by the lakes of the middle region, and was also obtainable upon the plateau. Bitumen and naphtha were produced by sources in the low country. The mountains contained most of the important metals and a certain number of valuable gems. The pearls of the Gulf acquired early a great reputation, and a regular fishery was established for them before the time of Alexander.

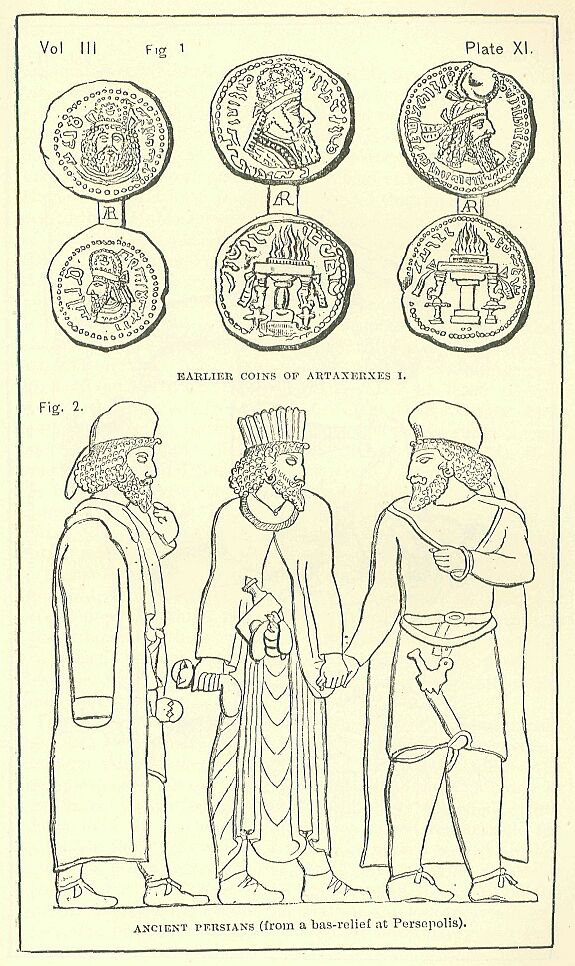

But the most celebrated of all the products of Persia were its men. The "scant and rugged country" gave birth, as Cyrus the Great is said to have observed, to a race brave, hardy, and enduring, calculated not only to hold its own against aggressors, but to extend its sway and exercise dominion over the Western Asiatics generally. The Aryan family is the one which, of all the races of mankind, is the most self-asserting, and has the greatest strength, physical, moral, and intellectual. The Iranian branch of it, whereto the Persians belonged, is not perhaps so gifted as some others; but it has qualities which place it above most of those by which Western Asia was anciently peopled. In the primitive times, from Cyrus the Great to Darius Hystaspis, the Persians seem to have been rude mountaineers, probably not very unlike the modern Kurds and Lurs, who inhabit portions of the same chain which forms the heart of the Persian country. Their physiognomy was handsome. A high straight forehead, a long slightly aquiline nose, a short and curved upper lip, a well-rounded chin, characterized the Persian. The expression of his face was grave and noble. He had abundant hair, which he wore very artificially arranged. Above and round the brow it was made to stand away from the face in short crisp curls; on the top of the head it was worn smooth; at the back of the head it was again trained into curls, which followed each other in several rows from the level of the forehead to the nape of the neck. The moustache was always cultivated, and curved in a gentle sweep. A beard and whiskers were worn, the former sometimes long and pendent, like the Assyrian, but more often clustering around the chin in short close curls. The figure was well-formed, but somewhat stout; the carriage was dignified and simple. [PLATE XI, Fig. 1.]

Simplicity of manners prevailed during this period. At the court there was some luxury; but the bulk of the nation, living in their mountain territory, and attached to agriculture and hunting, maintained the habits of their ancestors, and were a somewhat rude though not a coarse people. The dress commonly worn was a close-fitting shirt or tunic of leather, descending to the knee, and with sleeves that reached down to the wrist. Round the tunic was worn a belt or sash, which was tied in front. The head was protected by a loose felt cap and the feet by a sort of high shoe or low boot. The ordinary diet was bread and cress-seed, while the sole beverage was water. In the higher ranks, of course, a different style of living prevailed; the elegant and flowing "Median robe" was worn; flesh of various kinds was eaten; much wine was consumed; and meals were extended to a great length; The Persians, however, maintained during this period a general hardihood and bravery which made them the most dreaded adversaries of the Greeks, and enabled them to maintain an unquestioned dominion over the other native races of Western Asia.

As time went on, and their monarchs became less warlike, and wealth accumulated, and national spirit decayed, the Persian character by degrees deteriorated, and sank, even under the Achaemenian kings, to a level not much superior to that of the ordinary Asiatic. The Persian antagonists of Alexander were pretty nearly upon a par with the races which in Hindustan have yielded to the British power; they occasionally fought with gallantry, but they were deficient in resolution, in endurance, in all the elements of solid strength; and they were quite unable to stand their ground against the vigor and dash of the Macedonians and the Greeks. Whether physically they were very different from the soldiers of Cyrus may be doubted, but morally they had fallen far below the ancient standard; their self-respect their love of country, their attachment to their monarch had diminished; no one showed any great devotion to the cause for which he fought; after two defeats the empire wholly collapsed; and the Persians submitted, apparently without much reluctance, to the Helleno-Macedonian yoke.

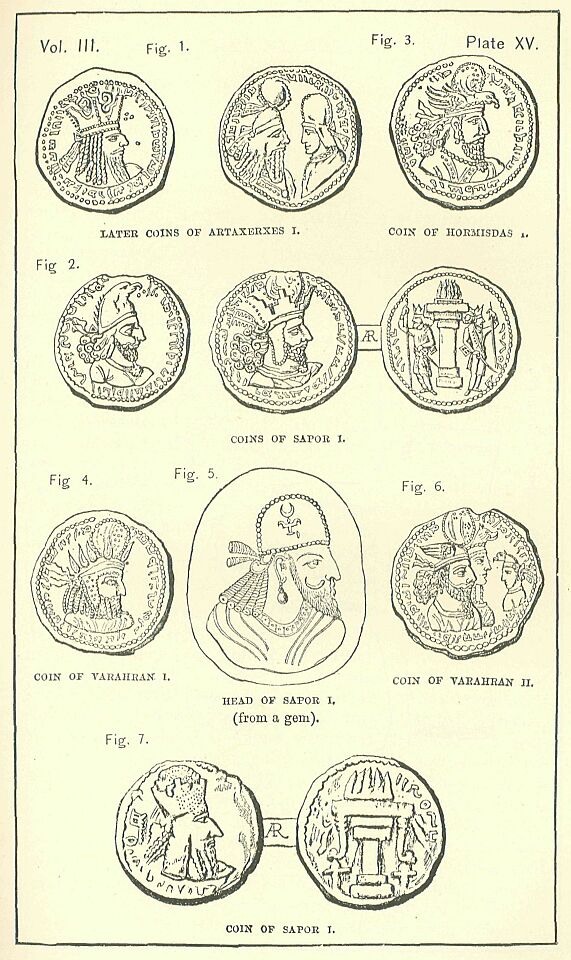

Five centuries and a half of servitude could not much improve or elevate the character of the people. Their fall from power, their loss of wealth and of dominion did indeed advantage them in one way: it but an end to that continually advancing sloth and luxury which had sapped the virtue of the nation, depriving it of energy, endurance, and almost every manly excellence. It dashed the Persians back upon the ground whence they had sprung, and whence, Antseus-like, they proceeded to derive fresh vigor and vital force. In their "scant and rugged" fatherland, the people of Cyrus once more recovered to a great extent their ancient prowess and hardihood—their habits became simplified, their old patriotism revived, their self-respect grew greater. But while adversity thus in some respects proved its "sweet uses" upon them, there were other respects in which submission to the yoke of the Greeks, and still more to that of the Parthians, seems to have altered them for the worse rather than for the better. There is a coarseness and rudeness about the Sassanian Persians which we do not observe in Achaemenian times. The physique of the nation is not indeed much altered. Nearly the same countenance meets us in the sculptures of Artaxerxes, the son of Babek, of Sapor, and of their successors, with which we are familiar from the bas-reliefs of Darius Hystapis and Xerxes. There is the same straight forehead, the same aquiline nose, the same well-shaped mouth, the same abundant hair. The form is, however, coarser and clumsier; the expression is less refined; and the general effect produced is that the people have, even physically, deteriorated. The mental and aesthetic standard seems still more to have sunk. There is no evidence that the Persians of Sassanian times possessed the governmental and administrative ability of Darius Hystapis or Artaxerxes Ochus. Their art, though remarkable, considering the almost entire disappearance of art from Western Asia under the Parthians, is, compared with that of Achaemenian times, rude and grotesque. In architecture, indeed, they are not without merit though even here the extent to which they were indebted to the Parthians, which cannot be exactly determined, must lessen our estimation of them; but their mimetic art, while not wanting in spirit, is remarkably coarse and unrefined. As a later chapter will be devoted to this subject, no more need be said upon it here. It is sufficient for our present purpose to note that the impression which we obtain from the monumental remains of the Sassanian Persians accords with what is to be gathered of them from the accounts of the Romans and the Greeks. The great Asiatic revolution of the year A.D. 226 marks a revival of the Iranic nationality from the depressed state into which it had sunk for more than five hundred years; but the revival is not full or complete. The Persians of the Sassanian kingdom are not equal to those of the time between Cyrus the Great and Darius Codomannus; they have ruder manners, a grosser taste, less capacity for government and organization; they have, in fact, been coarsened by centuries of Tartar rule; they are vigorous, active, energetic, proud, brave; but in civilization and refinement they do not rank much above their Parthian predecessors. Western Asia gained, perhaps, something, but it did not gain much, from the substitution of the Persians for the Parthians as the dominant power. The change is the least marked among the revolutions which the East underwent between the accession of Cyrus and the conquests of Timour. But it is a change, on the whole, for the better. It is accompanied by a revival of art, by improvements in architecture; it inaugurates a religious revolution which has advantages. Above all, it saves the East from stagnation. It is one among many of those salutary shocks which, in the political as in the natural world, are needed from time to time to stimulate action and prevent torpor and apathy.

CHAPTER III.

Reign of Artaxerxes I. Stories told of him. Most probable account of his Descent, Rank, and Parentage. His Contest with Artabanus. First War with Chosroes of Armenia. Contest with Alexander Severus. Second War with Chosroes and conquest of Armenia. Religious Reforms. Internal Administration and Government. Art. Coinage. Inscriptions.

Around the cradle of an Oriental sovereign who founds a dynasty there cluster commonly a number of traditions, which have, more or less, a mythical character. The tales told of the Great, which even Herodotus set aside as incredible, have their parallels in narratives that were current within one or two centuries with respect to the founder of the Second Persian Empire, which would not have disgraced the mythologers of Achaemenian times. Artaxerxes, according to some, was the son of a common soldier who had an illicit connection with the wife of a Persian cobbler and astrologer, a certain Babek or Papak, an inhabitant of the Cadusian country and a man of the lowest class. Papak, knowing by his art that the soldier's son would attain a lofty position, voluntarily ceded his rights as husband to the favorite of fortune, and bred up as his own the issue of this illegitimate commerce, who, when he attained to manhood, justified Papak's foresight by successfully revolting from Artabanus and establishing the new Persian monarchy. Others said that the founder of the new kingdom was a Parthian satrap, the son of a noble, and that, having long meditated revolt, he took the final plunge in consequence of a prophecy uttered by Artabanus, who was well skilled in magical arts, and saw in the stars that the Parthian empire was threatened with destruction. Artabanus, on a certain occasion, when he communicated this prophetic knowledge to his wife, was overheard by one of her attendants, a noble damsel named Artaducta, already affianced to Artaxerxes and a sharer in his secret counsels. At her instigation he hastened his plans, raised the standard of revolt, and upon the successful issue of his enterprise made her his queen. Miraculous circumstances were freely interwoven with these narratives, and a result was produced which staggered the faith even of such a writer as Moses of Chorene, who, desiring to confine himself to what was strictly true and certain, could find no more to say of Artaxerxes's birth and origin than that he was the son of a certain Sasan, and a native of Istakr, or Persepolis.

Even, however, the two facts thus selected as beyond criticism by Moses are far from being entitled to implicit credence. Artaxerxes, the son of Sasan according to Agathangelus and Moses, is the same as Papak (or Babek) in his own and his son's inscriptions. The Persian writers generally take the same view, and declare that Sasan was a remoter ancestor of Artaxerxes, the acknowledged founder of the family, and not Artaxerxes' father. In the extant records of the new Persian Kingdom, the coins and the inscriptions, neither Sasan nor the gentilitial term derived from it, Sasanidae, has any place; and though it would perhaps be rash to question on this account the employment of the term Sasanidae by the dynasty, yet we may regard it as really "certain" that the father of Artaxerxes was named, not Sasan, but Papak; and that, if the term Sasanian was in reality a patronymic, it was derived, like the term "Achaemenian," from some remote progenitor whom the royal family of the new empire believed to have been their founder.

The native country of Artaxerxes is also variously stated by the authorities. Agathangelus calls him an Assyrian, and makes the Assyrians play an important part in his rebellion. Agathias says that he was born in the Cadusian country, or the low tract south-west of the Caspian, which belonged to Media rather than to Assyria or Persia. Dio Cassius, and Herodian, the contemporaries of Artaxerxes, call him a Persian; and there can be no reasonable doubt that they are correct in so doing. Agathangelus allows the predominantly Persian character of his revolt, and Agathias is apparently unaware that the Cadusian country was no part of Persia. The statement that he was a native of Persepolis (Istakr) is first found in Moses of Chorene. It may be true, but it is uncertain; for it may have grown out of the earlier statement of Agathangelus, that he held the government of the province of Istakr. We can only affirm with confidence that the founder of the new Persian monarchy was a genuine Persian, without attempting to determine positively what Persian city or province had the honor of producing him.

A more interesting question, and one which will be found perhaps to admit of a more definite answer, is that of the rank and station in which Artaxerxes was born. We have seen that Agathias (writing ab. A.D. 580) called him the supposititious son of a cobbler. Others spoke of him as the child of a shepherd; while some said that his father was "an inferior officer in the service of the government." But on the other hand, in the inscriptions which Artaxerxes himself setup in the neighborhood of Persepolis, he gives his father, Papak, the title of "King." Agathangelus calls him a "noble" and "satrap of Persepolitan government;" while Herodian seems to speak of him as "king of the Persians," before his victories over Artabanus. On the whole, it is perhaps most probable that, like Cyrus, he was the hereditary monarch of the subject kingdom of Persia, which had always its own princes under the Parthians, and that thus he naturally and without effort took the leadership of the revolt when circumstances induced his nation to rebel and seek to establish its independence. The stories told of his humble origin, which are contradictory and improbable, are to be paralleled with those which made Cyrus the son of a Persian of moderate rank, and the foster-child of a herdsman. There is always in the East a tendency towards romance and exaggeration; and when a great monarch emerges from a comparatively humble position, the humility and obscurity of his first condition are intensified, to make the contrast more striking between his original low estate and his ultimate splendor and dignity.

The circumstances of the struggle between Artaxerxes and. Artabanus are briefly sketched by Dio Cassius and Agathangelus, while they are related more at large by the Persian writers. It is probable that the contest occupied a space of four or five years. At first, we are told, Artabanus neglected to arouse himself, and took no steps towards crushing the rebellion, which was limited to an assertion of the independence of Persia Proper, or the province of Fars. After a time the revolted vassal, finding himself unmolested, was induced to raise his thoughts higher, and commenced a career of conquest. Turning his arms eastward, he attacked Kerman (Carmania), and easily succeeded in reducing that scantily-peopled tract under his dominion. He then proceeded to menace the north, and, making war in that quarter, overran and attached to his kingdom some of the outlying provinces of Media. Roused by these aggressions, the Parthian monarch at length took the field, collected an army consisting in part of Parthians, in part of the Persians who continued faithful to him, against his vassal, and, invading Persia, soon brought his adversary to a battle. A long and bloody contest followed, both sides suffering great losses; but victory finally declared itself in favor of Artaxerxes, through the desertion to him, during the engagement, of a portion of his enemy's forces. A second conflict ensued within a short period, in which the insurgents were even more completely successful; the carnage on the side of the Parthians was great, the loss of the Persians small; and the great king fled precipitately from the field. Still the resources of Parthia were equal to a third trial of arms. After a brief pause, Artabanus made a final effort to reduce his revolted vassal; and a last engagement took place in the plain of Hormuz, which was a portion of the Jerahi valley, in the beautiful country between Bebahan and Shuster. Here, after a desperate conflict, the Parthian monarch suffered a third and signal defeat; his army was scattered; and he himself lost his life in the combat. According to some, his death was the result of a hand-to-hand conflict with his great antagonist, who, pretending to fly, drew him on, and then pierced his heart with an arrow.

The victory of Hormuz gave to Artaxerxes the dominion of the East; but it did not secure him this result at once, or without further struggle. Artabanus had left sons; and both in Bactria and Armenia there were powerful branches of the Arsacid family, which could not see unmoved the downfall of their kindred in Parthia. Chosroes, the Armenian monarch, was a prince of considerable ability, and is said to have been set upon his throne by Artabanus, whose brother he was, according to some writers. At any rate he was an Arsacid; and he felt keenly the diminution of his own influence involved in the transfer to an alien race of the sovereignty wielded for five centuries by the descendants of the first Arsaces. He had set his forces in motion, while the contest between Artabanus and Artaxerxes was still in progress, in the hope of affording substantial help to his relative. But the march of events was too rapid for him; and, ere he could strike a blow, he found that the time for effectual action had gone by, that Artabanus was no more, and that the dominion of Artaxerxes was established over most of the countries which had previously formed portions of the Parthian Empire. Still, he resolved to continue the struggle; he was on friendly terms with Rome, and might count on an imperial contingent; he had some hope that the Bactrian Arsacidae would join him; at the worst, he regarded his own power as firmly fixed and as sufficient to enable him to maintain an equal contest with the new monarchy. Accordingly he took the Parthian Arsacids under his protection, and gave them a refuge in the Armenian territory. At the same time he negotiated with both Balkh and Rome, made arrangements with the barbarians upon his northern frontier to lend him aid, and, having collected a large army, invaded the new kingdom on the north-west, and gained certain not unimportant successes. According to the Armenian historians, Artaxerxes lost Assyria and the adjacent regions; Bactria wavered; and, after the struggle had continued for a year or two, the founder of the second Persian empire was obliged to fly ignominiously to India! But this entire narrative seems to be deeply tinged with the vitiating stain of intense national vanity, a fault which markedly characterizes the Armenian writers, and renders them, when unconfirmed by other authorities, almost worthless. The general course of events, and the position which Artaxerxes takes in his dealings with Rome (A.D. 229-230), sufficiently indicate that any reverses which he sustained at this time in his struggle with Chosroes and the unsubmitted Arsacidae must have been trivial, and that they certainly had no greater result than to establish the independence of Armenia, which, by dint of leaning upon Rome, was able to maintain itself against the Persian monarch and to check the advance of the Persians in North-Western Asia.

Artaxerxes, however, resisted in this quarter, and unable to overcome the resistance, which he may have regarded as deriving its effectiveness (in part at least) from the support lent it by Rome, determined (ab. A.D. 229) to challenge the empire to an encounter. Aware that Artabanus, his late rival, against whom he had measured himself, and whose power he had completely overthrown, had been successful in his war with Macrinus, had gained the great battle of Nisibis, and forced the Imperial State to purchase an ignominious peace by a payment equal to nearly two millions of our money, he may naturally have thought that a facile triumph was open to his arms in this direction. Alexander Severus, the occupant of the imperial throne, was a young man of a weak character, controlled in a great measure by his mother, Julia Mamaea, and as yet quite undistinguished as a general. The Roman forces in the East were known to be licentious and insubordinate; corrupted by the softness of the climate and the seductions of Oriental manners, they disregarded the restraints of discipline, indulged in the vices which at once enervate the frame and lower the moral character, had scant respect for their leaders, and seemed a defence which it would be easy to overpower and sweep away. Artaxerxes, like other founders of great empires, entertained lofty views of his abilities and his destinies; the monarchy which he had built up in the space of some five or six years was far from contenting him; well read in the ancient history of his nation, he sighed after the glorious days of Cyrus the Great and Darius Hystaspis, when all Western Asia from the shores of the AEgean to the Indian desert, and portions of Europe and Africa, had acknowledged the sway of the Persian king. The territories which these princes had ruled he regarded as his own by right of inheritance; and we are told that he not only entertained, but boldly published, these views. His emissaries everywhere declared that their master claimed the dominion of Asia as far as the AEgean Sea and the Propontis. It was his duty and his mission to recover to the Persians their pristine empire. What Cyrus had conquered, what the Persian kings had held from that time until the defeat of Codomannus by Alexander, was his by indefeasible right, and he was about to take possession of it.

Nor were these brave words a mere brutum fulmen. Simultaneously with the putting forth of such lofty pretensions the troops of the Persian monarch crossed the Tigris and spread themselves over the entire Roman province of Mesopotamia, which was rapidly overrun and offered scarcely any resistance. Severus learned at the same moment the demands of his adversary and the loss of one of his best provinces. He heard that his strong posts upon the Euphrates, the old defences of the empire in this quarter, were being attacked, and that Syria daily expected the passage of the invaders. The crisis was one requiring prompt action; but the weak and inexperienced youth was content to meet it with diplomacy, and, instead of sending an army to the East, despatched ambassadors to his rival with a letter. "Artaxerxes," he said, "ought to confine himself to his own territories and not seek to revolutionize Asia; it was unsafe, on the strength of mere unsubstantial hopes, to commence a great war. Every one should be content with keeping what belonged to him. Artaxerxes would find war with Rome a very different thing from the contests in which he had been hitherto engaged with barbarous races like his own. He should call to mind the successes of Augustus and Trajan, and the trophies carried off from the East by Lucius Verus and by Septimius Severus."

The counsels of moderation have rarely much effect in restraining princely ambition. Artaxerxes replied by an embassy in which he ostentatiously displayed the wealth and magnificence of Persia; but, so far from making any deduction from his original demands, he now distinctly formulated them, and required their immediate acceptance. "Artaxerxes, the Great King," he said, "ordered the Romans and their ruler to take their departure forthwith from Syria and the rest of Western Asia, and to allow the Persians to exercise dominion over Ionia and Caria and the other countries within the AEgean and the Euxine, since these countries belonged to Persia by right of inheritance." A Roman emperor had seldom received such a message; and Alexander, mild and gentle as he was by nature, seems to have had his equanimity disturbed by the insolence of the mandate. Disregarding the sacredness of the ambassadorial character, he stripped the envoys of their splendid apparel, treated them as prisoners of war, and settled them as agricultural colonists in Phrygia. If we may believe Herodian, he even took credit to himself for sparing their lives, which he regarded as justly forfeit to the offended majesty of the empire.

Meantime the angry prince, convinced at last against his will that negotiations with such an enemy were futile, collected an army and began his march towards the East. Taking troops from the various provinces through which he passed, he conducted to Antioch, in the autumn of A.D. 231, a considerable force, which was there augmented by the legions of the East and by troops drawn from Egypt and other quarters. Artaxerxes, on his part, was not idle. According to Soverus himself, the army brought into the field by the Persian monarch consisted of one hundred and twenty thousand mailed horsemen, of eighteen hundred scythed chariots, and of seven hundred trained elephants, bearing on their backs towers filled with archers; and though this pretended host has been truly characterized as one "the like of which is not to be found in Eastern history, and has scarcely been imagined in Eastern romance," yet, allowing much for exaggeration, we may still safely conclude that great exertions had been made on the Persian side, that their forces consisted of the three arms mentioned, and that the numbers of each were large beyond ordinary precedent. The two adversaries were thus not ill-matched; each brought the flower of his troops to the conflict; each commanded the army, on which his dependence was placed, in person; each looked to obtain from the contest not only an increase of military glory, but substantial fruits of victory in the shape of plunder or territory.

It might have been expected that the Persian monarch, after the high tone which he had taken, would have maintained an aggressive attitude, have crossed the Euphrates, and spread the hordes at his disposal over Syria, Cappadocia, and Asia Minor. But it seems to be certain that he did not do so, and that the initiative was taken by the other side. Probably the Persian arms, as inefficient in sieges as the Parthian, were unable to overcome the resistance offered by the Roman forts upon the great river; and Artaxerxes was too good a general to throw his forces into the heart of an enemy's country without having first secured a safe retreat. The Euphrates was therefore crossed by his adversary in the spring of A.D. 232; the Roman province of Mesopotamia was easily recovered; and arrangements were made by which it was hoped to deal the new monarchy a heavy blow, if not actually to crush and conquer it.

Alexander divided his troops into three bodies. One division was to act towards the north, to take advantage of the friendly disposition of Chosroes, king of Armenia, and, traversing his strong mountain territory, to direct its attack upon Media, into which Armenia gave a ready entrance. Another was to take a southern line, and to threaten Persia Proper from the marshy tract about the junction of the Euphrates with the Tigris, a portion of the Babylonian territory. The third and main division, which was to be commanded by the emperor in person, was to act on a line intermediate between the other two, which would conduct it to the very heart of the enemy's territory, and at the same time allow of its giving effective support to either of the two other divisions if they should need it.

The plan of operations appears to have been judiciously constructed, and should perhaps be ascribed rather to the friends whom the youthful emperor consulted than to his own unassisted wisdom. But the best designed plans may be frustrated by unskilfulness or timidity in the execution; and it was here, if we may trust the author who alone gives us any detailed account of the campaign, that the weakness of Alexander's character showed itself. The northern army successfully traversed Armenia, and, invading Media, proved itself in numerous small actions superior to the Persian force opposed to it, and was able to plunder and ravage the entire country at its pleasure. The southern division crossed Mesopotamia in safety, and threatened to invade Persia Proper. Had Alexander with the third and main division kept faith with the two secondary armies, had he marched briskly and combined his movements with theirs, the triumph of the Roman arms would have been assured. But, either from personal timidity or from an amiable regard for the anxieties of his mother Mamsea, he hung back while his right and left wings made their advance, and so allowed the enemy to concentrate their efforts on these two isolated bodies. The army in Media, favored by the rugged character of the country, was able to maintain its ground without much difficulty; but that which had advanced by the line of the Euphrates and Tigris, and which was still marching through the boundless plains of the great alluvium, found itself suddenly beset by a countless host, commanded by Artaxerxes in person, and, though it struggled gallantly, was overwhelmed and utterly destroyed by the arrows of the terrible Persian bowmen. Herodian says, no doubt with some exaggeration, that this was the greatest calamity which had ever befallen the Romans. It certainly cannot compare with Cannae, with the disaster of Varus, or even with the similar defeat of Crassus in a not very distant region. But it was (if rightly represented by Herodian) a terrible blow. It absolutely determined the campaign. A Caesar or a Trajan might have retrieved such a loss. An Alexander Severus was not likely even to make an attempt to do so. Already weakened in body by the heat of the climate and the unwonted fatigues of war, he was utterly prostrated in spirit by the intelligence when it reached him. The signal was at once given for retreat. Orders were sent to the corps d' armee which occupied Media to evacuate its conquests and to retire forthwith upon the Euphrates. These orders were executed, but with difficulty. Winter had already set in throughout the high regions; and in its retreat the army of Media suffered great losses through the inclemency of the climate, so that those who reached Syria were but a small proportion of the original force. Alexander himself, and the army which he led, experienced less difficulty; but disease dogged the steps of this division, and when its columns reached Antioch it was found to be greatly reduced in numbers by sickness, though it had never confronted an enemy. The three armies of Severus suffered not indeed equally, but still in every case considerably, from three distinct causes—sickness, severe weather, and marked inferiority to the enemy. The last-named cause had annihilated the southern division; the northern had succumbed to climate; the main army, led by Severus himself, was (comparatively speaking) intact, but even this had been decimated by sickness, and was not in a condition to carry on the war with vigor. The result of the campaign had thus been altogether favorable to the Persians, but yet it had convinced Artaxerxes that Rome was more powerful than he had thought. It had shown him that in imagining the time had arrived when they might be easily driven out of Asia—he had made a mistake. The imperial power had proved itself strong enough to penetrate deeply within his territory, to ravage some of his best provinces, and to threaten his capital. The grand ideas with which he had entered upon the contest had consequently to be abandoned; and it had to be recognized that the struggle with Rome was one in which the two parties were very evenly matched, one in which it was not to be supposed that either side would very soon obtain any decided preponderance. Under these circumstances the grand ideas were quietly dropped; the army which had been gathered together to enforce them was allowed to disperse, and was not required within any given time to reassemble; it is not unlikely that (as Niebuhr conjectures) a peace was made, though whether Rome ceded any of her territory by its terms is exceedingly doubtful. Probably the general principle of the arrangement was a return to the status quo ante bellum, or, in other words, the acceptance by either side, as the true territorial limits between Rome and Persia, of those boundaries which had been previously held to divide the imperial possessions from the dominions of the Arsacidse.

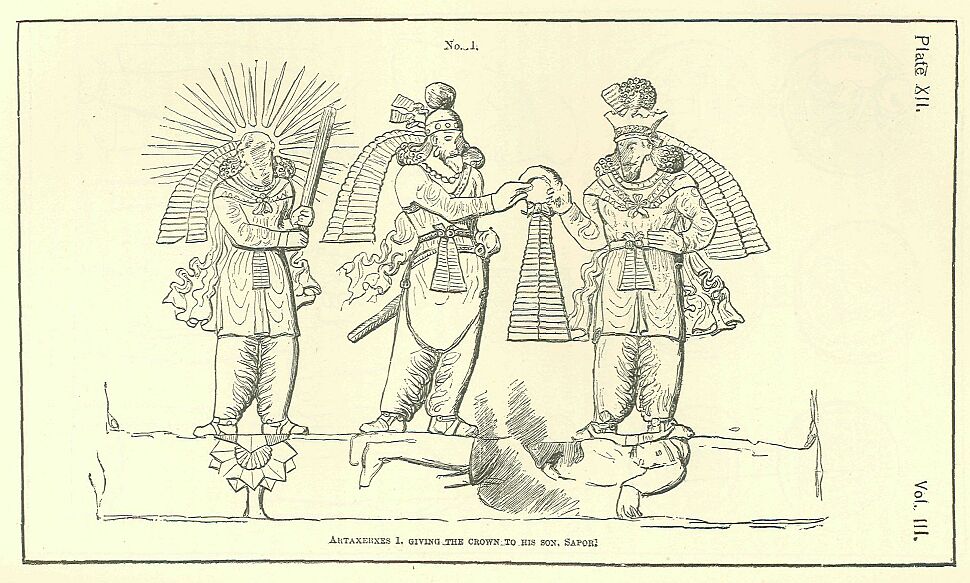

The issue of the struggle was no doubt disappointing to Artaxerxes; but if, on the one hand, it dispelled some illusions and proved to him that the Roman State, though verging to its decline, nevertheless still possessed a vigor and a life which he had been far from anticipating, on the other hand it left him free to concentrate his efforts on the reduction of Armenia, which was really of more importance to him, from Armenia being the great stronghold of the Arsacid power, than the nominal attachment to the empire of half-a-dozen Roman provinces. So long as Arsacidae maintained themselves in a position of independence and substantial power so near the Persian borders, and in a country of such extent and such vast natural strength as Armenia, there could not but be a danger of reaction, of the nations again reverting to the yoke whereto they had by long use become accustomed, and of the star of the Sasanidae paling before that of the former masters of Asia. It was essential to the consolidation of the new Persian Empire that Armenia should be subjugated, or at any rate that Arsacidae should cease to govern it; and the fact that the peace which appears to have been made between Rome and Persia, A.D. 232, set Artaxerxes at liberty to direct all his endeavors to the establishment of such relations between his own state and Armenia as he deemed required by public policy and necessary for the security of his own power, must be regarded as one of paramount importance, and as probably one of the causes mainly actuating him in the negotiations and inclining him to consent to peace on any fair and equitable terms. Consequently, the immediate result of hostilities ceasing between Persia and Rome was their renewal between Persia and Armenia. The war had indeed, in one sense, never ceased; for Chosroes had been an ally of the Romans during the campaign of Severus, and had no doubt played a part in the invasion and devastation of Media which have been described above. But, the Romans having withdrawn, he was left wholly dependent on his own resources; and the entire strength of Persia was now doubtless brought into the field against him. Still he defended himself with such success, and caused Artaxerxes so much alarm, that after a time that monarch began to despair of ever conquering his adversary by fair means, and cast about for some other mode of accomplishing his purpose. Summoning an assembly of all the vassal kings, the governors, and the commandants throughout the empire, he besought them to find some cure for the existing distress, at the same time promising a rich reward to the man who should contrive an effectual remedy. The second place in the kingdom should be his; he should have dominion over one half of the Arians; nay, he should share the Persian throne with Artaxerxes himself, and hold a rank and dignity only slightly inferior. We are told that these offers prevailed with a noble of the empire, named Anak, a man who had Arsacid blood in his veins, and belonged to that one of the three branches of the old royal stock which had long been settled at Bactria (Balkh), and that he was induced thereby to come forward and undertake the assassination of Chosroes, who was his near relative and would not be likely to suspect him of an ill intent. Artaxerxes warmly encouraged him in his design, and in a little time it was successfully carried out. Anak, with his wife, his children, his brother, and a train of attendants, pretended to take refuge in Armenia from the threatened vengeance of his sovereign, who caused his troops to pursue him, as a rebel and deserter, to the very borders of Armenia. Unsuspicious of any evil design, Ohosroes received the exiles with favor, discussed with them his plans for the subjugation of Persia, and, having sheltered them during the whole of the autumn and winter, proposed to them in the spring that they should accompany him and take part in the year's campaign. Anak, forced by this proposal to precipitate his designs, contrived a meeting between himself, his brother, and Chosroes, without attendants, on the pretext of discussing plans of attack, and, having thus got the Armenian monarch at a disadvantage, drew sword upon him, together with his brother, and easily put him to death. The crime which he had undertaken was thus accomplished; but he did not live to receive the reward promised him for it. Armenia rose in arms on learning the foul deed wrought upon its king; the bridges and the few practicable outlets by which the capital could be quitted were occupied by armed men; and the murderers, driven to desperation, lost their lives in an attempt to make their escape by swimming the river Araxes. Thus Artaxerxes obtained his object without having to pay the price that he had agreed upon; his dreaded rival was removed; Armenia lay at his mercy; and he had not to weaken his power at home by sharing it with an Arsacid partner.

The Persian monarch allowed the Armenians no time to recover from the blow which he had treacherously dealt them. His armies at once entered their territory and carried everything before them. Chosroes seems to have had no son of sufficient age to succeed him, and the defence of the country fell upon the satraps, or governors of the several provinces. These chiefs implored the aid of the Roman emperor, and received a contingent; but neither were their own exertions nor was the valor of their allies of any avail. Artaxerxes easily defeated the confederate army, and forced the satraps to take refuge in Roman territory. Armenia submitted to his arms, and became an integral portion of his empire. It probably did not greatly trouble him that Artavasdes, one of the satraps, succeeded in carrying off one of the sons of Chosroes, a boy named Tiridates, whom he conveyed to Rome, and placed under the protection of the reigning emperor.

Such were the chief military successes of Artaxerxes. The greatest of our historians, Gibbon, ventures indeed to assign to him, in addition, "some easy victories over the wild Scythians and the effeminate Indians." But there is no good authority for this statement; and on the whole it is unlikely that he came into contact with either nation. His coins are not found in Afghanistan; and it may be doubted whether he ever made any eastern expedition. His reign was not long; and it was sufficiently occupied by the Roman and Armenian wars, and by the greatest of all his works, the reformation of religion.

The religious aspect of the insurrection which transferred the headship of Western Asia from the Parthians to the Persians, from Artabanus to Artaxerxes, has been already noticed; but we have now to trace, so far as we can, the steps by which the religious revolution was accomplished, and the faith of Zoroaster, or what was believed to be such, established as the religion of the State throughout the new empire. Artaxerxes, himself (if we may believe Agathias) a Magus, was resolved from the first that, if his efforts to shake off the Parthian yoke succeeded, he would use his best endeavors to overthrow the Parthian idolatry and install in its stead the ancestral religion of the Persians. This religion consisted of a combination of Dualism with a qualified creature-worship, and a special reverence for the elements, earth, air, water, and fire. Zoroastrianism, in the earliest form which is historically known to us, postulated two independent and contending principles—a principle of good, Ahura-Mazda, and a principle of evil, Angro-Mainyus. These beings, who were coeternal and coequal, were engaged in a perpetual struggle for supremacy; and the world was the battle-field wherein the strife was carried on. Each had called into existence numerous inferior beings, through whose agency they waged their interminable conflict. Ahura-Mazda (Oromazdos, Ormazd) had created thousands of angelic beings to perform his will and fight on his side against the Evil One; and Alngro-Mainyus (Arimanius, Ahriman) had equally on his part called into being thousands of malignant spirits to be his emissaries in the world, to do his work, and fight his battles. The greater of the powers called into being by Ahura-Mazda were proper objects of the worship of man, though, of course, his main worship was to be given to Ahura-Mazda. Angro-Mainyus was not to be worshipped, but to be hated and feared. With this dualistic belief had been combined, at a time not much later than that of Darius Hystaspis, an entirely separate system, the worship of the elements. Fire, air, earth, and water were regarded as essentially holy, and to pollute any of them was a crime. Fire was especially to be held in honor; and it became an essential part of the Persian religion to maintain perpetually upon the fire-altars the sacred flame, supposed to have been originally kindled from heaven, and to see that it never went out. Together with this elemental worship was introduced into the religion a profound regard for an order of priests called Magians, who interposed themselves between the deity and the worshipper, and claimed to possess prophetic powers. This Magian order was a priest-caste, and exercised vast influence, being internally organized into a hierarchy containing many ranks, and claiming a sanctity far above that of the best laymen.

Artaxerxes found the Magian order depressed by the systematic action of the later Parthian princes, who had practically fallen away from the Zoroastrian faith and become mere idolaters. He found the fire-altars in ruins, the sacred flame extinguished, the most essential of the Magian ceremonies and practices disregarded. Everywhere, except perhaps in his own province of Persia Proper, he found idolatry established. Temples of the sun abounded, where images of Mithra were the object of worship, and the Mithraic cult was carried out with a variety of imposing ceremonies. Similar temples to the moon existed in many places; and the images of the Arsacidae were associated with those of the sun and moon gods, in the sanctuaries dedicated to them. The precepts of Zoroaster were forgotten. The sacred compositions which bore that sage's name, and had been handed down from a remote antiquity, were still indeed preserved, if not in a written form, yet in the memory of the faithful few who clung to the old creed; but they had ceased to be regarded as binding upon their consciences by the great mass of the Western Asiatics. Western Asia was a seething-pot, in which were mixed up a score of contradictory creeds, old and new, rational and irrational, Sabaism, Magism, Zoroastrianism, Grecian polytheism, teraphim-worship, Judaism, Chaldae mysticism, Christianity. Artaxerxes conceived it to be his mission to evoke order out of this confusion, to establish in lieu of this extreme diversity an absolute uniformity of religion.

The steps which he took to effect his purpose seem to have been the following. He put down idolatry by a general destruction of the images, which he overthrew and broke to pieces. He raised the Magian hierarchy to a position of honor and dignity such as they had scarcely enjoyed even under the later Achaemenian princes, securing them in a condition of pecuniary independence by assignments of lands, and also by allowing their title to claim from the faithful the tithe of all their possessions. He caused the sacred fire to be rekindled on the altars where it was extinguished, and assigned to certain bodies of priests the charge of maintaining the fire in each locality. He then proceeded to collect the supposed precepts of Zoroaster into a volume, in order to establish a standard of orthodoxy whereto he might require all to conform. He found the Zoroastrians themselves divided into a number of sects. Among these he established uniformity by means of a "general council," which was attended by Magi from all parts of the empire, and which settled what was to be regarded as the true Zoroastrian faith. According to the Oriental writers, this was effected in the following way: Forty thousand, or, according to others, eighty thousand Magi having assembled, they were successively reduced by their own act to four thousand, to four hundred, to forty, and finally to seven, the most highly respected for their piety and learning. Of these seven there was one, a young but holy priest, whom the universal consent of his brethren recognized as pre-eminent. His name was Arda-Viraf. "Having passed through the strictest ablutions, and drunk a powerful opiate, he was covered with a white linen and laid to sleep. Watched by seven of the nobles, including the king, he slept for seven days and nights; and, on his reawaking, the whole nation listened with believing wonder to his exposition of the faith of Ormazd, which was carefully written down by an attendant scribe for the benefit of posterity."

The result, however brought about, which must always remain doubtful, was the authoritative issue of a volume which the learned of Europe have now possessed for some quarter of a century, and which has recently been made accessible to the general reader by the labors of Spiegel. This work, the Zendavesta, while it may contain fragments of a very ancient literature, took its present shape in the time of Artaxerxes, and was probably then first collected from the mouths of the Zoroastrian priests and published by Arda-Viraf. Certain additions may since have been made to it; but we are assured that "their number is small," and that we "have no reason to doubt" that the text of the Avesta, in the days of Arda-Viraf, was on the whole exactly the same as at present. The religious system of the new Persian monarchy is thus completely known to us, and will be described minutely in a later chapter. At present we have to consider, not what the exact tenets of the Zoroastrians were, but only the mode in which Artaxerxes imposed them upon his subjects.

The next step, after settling the true text of the sacred volume, was to agree upon its interpretation. The language of the Avesta, though pure Persian, was of so archaic a type that none but the most learned of the Magi understood it; to the common people, even to the ordinary priest, it was a dead letter. Artaxerxes seems to have recognized the necessity of accompanying the Zend text with a translation and a commentary in the language of his own time, the Pehlevi or Huzvaresh. Such a translation and commentary exist; and though in part belonging to later Sassanian times, they reach back probably in their earlier portions to the era of Artaxerxes, who may fairly be credited with the desire to make the sacred book "understanded of the people."