.

THE GREAT PERSIAN WAR.

To

MY WINTER-FRIEND

HENRY FRANCIS PELHAM.

THE

GREAT PERSIAN WAR

AND ITS PRELIMINARIES;

A STUDY OF THE EVIDENCE, LITERARY

AND TOPOGRAPHICAL.

By G. B. GRUNDY, M.A.,

LECTURER AT BRASENOSE COLLEGE, AND UNIVERSITY LECTURER

IN CLASSICAL GEOGRAPHY, OXFORD.

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS.

NEW YORK:

CHARLES SCRIBNER’S SONS.

LONDON:

JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET.

1901.

PRINTED BY

WILLIAM CLOWES AND SONS LIMITED,

LONDON AND BECCLES.

PREFACE.

The publication of a version of an old old story which has been retold in modern times by famous writers, demands an apology even at this day of the making of many books. It can only be justified in case the writer has become possessed of new evidence on the history of the period with which the story is concerned, or has cause to think that the treatment of pre-existing evidence is not altogether satisfactory from a historical point of view.

I think I can justify my work on the first of these grounds; and I hope I shall be able to do so on the second.

Within the last half-century modern criticism of great ability has been brought to bear on the histories of Herodotus and Thucydides. Much of it has been of a destructive nature, and has tended to raise serious doubts as to the credibility of large and important parts of the narratives of those authors. I venture to think that, while some of this criticism must be accepted as sound by every careful student, much of it demands reconsideration.

A large part of it has been based upon topographical evidence. Of the nature of that evidence I should like to say a few words.

Until ten years ago the only military site of first-rate importance in Greek history which had been surveyed was the Strait of Salamis, which the Hydrographic Department of the English Admiralty had included in the field of its world-wide activity. A chart of Pylos made by the same [vi]department was also available, but was quite inadequate for the historical purpose.

Since that time Marathon has been included in the survey of Attica made by the German Staff Officers for the German Archæological Institute.

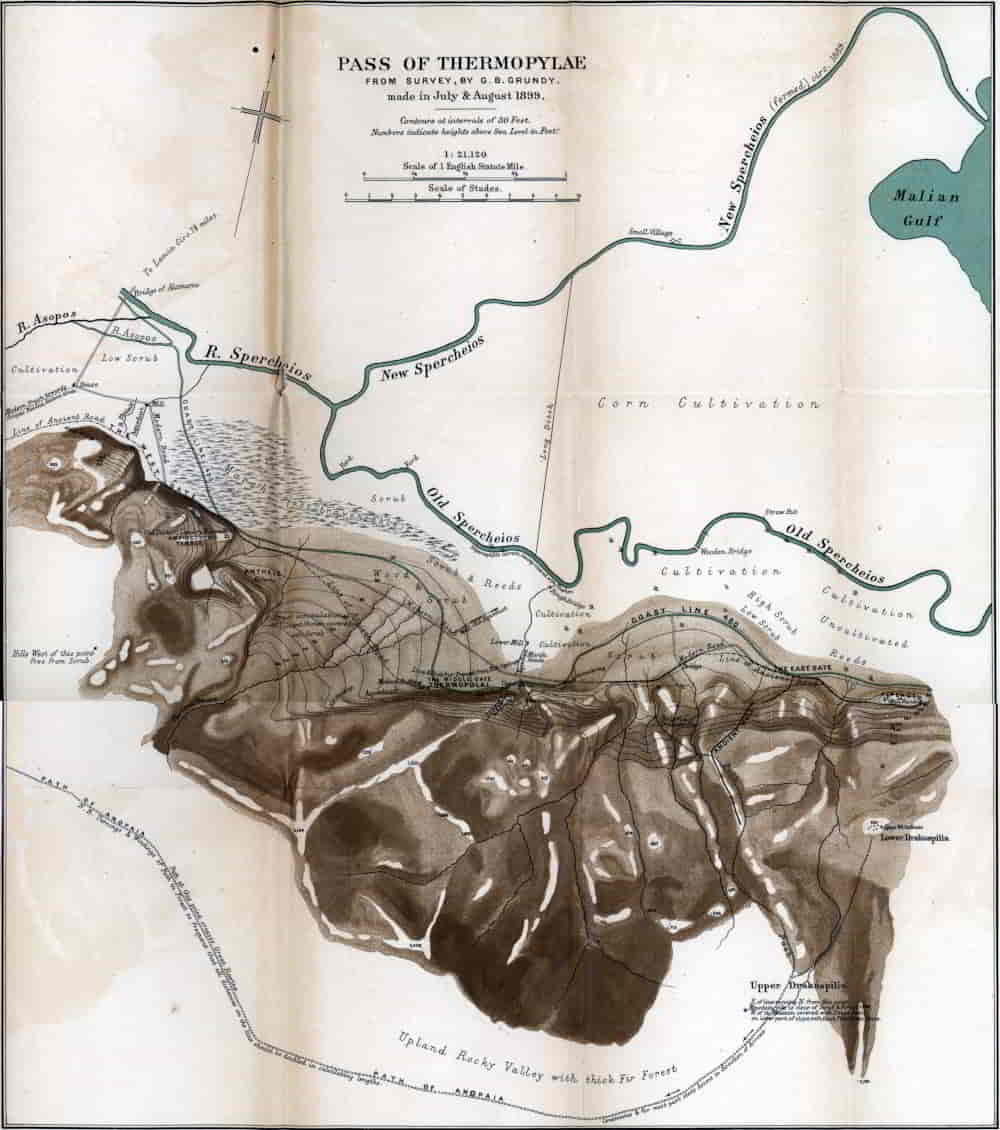

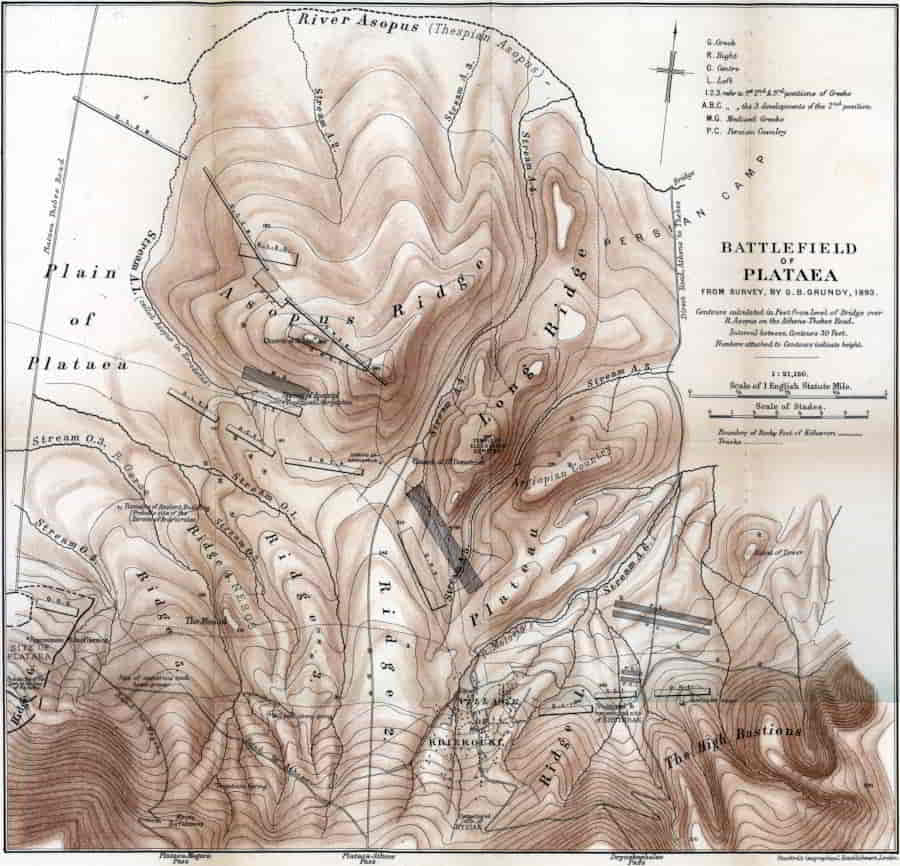

The surveys of Thermopylæ, Platæa, and Pylos, I have myself made at different times between 1892 and 1899. Pylos does not come within the scope of the present volume.

In the absence of these surveys, this side of Herodotean criticism was founded upon such sketches as Leake and other travellers had made of important historical sites, and upon the verbal description of them contained in their works.

It is superfluous to praise the labours of such inquirers. No amount of later investigation in Greek topography can ever supplant much that they have done. But I am quite certain that Leake would have been the last to claim any scientific accuracy for the sketch-maps which he made; and I think it will be agreed that maps without accuracy cannot be used for the historical criticism of highly elaborate narratives.

The present volume, deals exclusively with the Græco-Persian wars up to the end of 479 B.C. I propose to deal with the Hellenic warfare of the remainder of the fifth century in a separate volume.

Some of my conclusions are not in accord with the commonly accepted versions of the history of this period. But, when the circumstances of the work are considered, it will, I think, be conceded that such a result was almost inevitable.

I have supported my conclusions, especially in such cases as I believe them to be in disagreement with accepted views, by arguments taken from the evidence. Where those arguments are in my opinion likely to be of interest to the general reader, I have inserted them in the actual text; where they are of a very specialist character, I have put them in the form of notes.

I have but little more to say with regard to my own work in general. In the form in which I have presented [vii]it in this volume I have tried to make it constructive rather than destructive. I have, I believe, confined my destructive criticism to passages in which I found myself in conflict with accepted authorities on the subject who had presumably enjoyed equal opportunities with myself of becoming acquainted with the facts. I have purposely avoided criticism of those who, not having had the opportunity of visiting the scenes of action, but yet having made the best use of the evidence available at the time at which they wrote, have, in my opinion, been led into error by the defectiveness of the evidence they were obliged to use.

Early in the course of my inquiries, the results of investigation suggested to me that Herodotus’ evidence as an historian differs greatly in value, according as he is relating facts, or seeking to give the motives or causes lying behind them. Further investigation has tended to confirm this view. My conclusions on these two points will be made sufficiently clear in the course of this work.

In his purely military history Herodotus is dealing with a subject about which he seems to have possessed little, if any, special knowledge, and hardly any official information. The plan or design which lay behind the events which he relates can, therefore, only be arrived at, in the majority of instances, by means of an induction from the facts he mentions. This will, I think, adequately define and account for the method I have adopted in treating his evidence.

The necessity of employing various words indicating probability rather than certainty does not add adornment to style, but is inevitable under circumstances where the evidence is of the nature of that which is presented to any one who attempts to write the history of any part of the fifth century before Christ.

The spelling of Greek names is a difficulty at the present day. Many of the conventional forms are absolutely wrong. I do not, however, think that the time has yet come when it is convenient to write Sikelia, Athenai, Kerkura, etc. I have therefore used the conventional forms for well-known names, but have adopted the more correct forms for names less known, with one or two literal changes, such as “y” for upsilon, where the change [viii]is calculated to make the English pronunciation of the name approximate more closely to that of the original Greek.

As one who is from force of present circumstances laying aside, not without regret, a department of work which has been of infinite interest to him, and whose necessary discontinuance causes him the greatest regret, I may perhaps be allowed to speak briefly of my own experience to those Englishmen who contemplate work in Greece.

Firstly, as to motive: If you wish to take up such work because you have an enthusiasm for it, and because you feel that you possess certain knowledge and qualifications, take it up by all means; you will never regret having done so. It will give you that invaluable blessing,—a keen intellectual interest, lasting all your life.

But if your motive be to acquire thereby a commercial asset which may forward your future prospects, leave the work alone. You will, in the present state of feeling in England, forward those prospects much more effectively by other means.

In all work in Greece malaria is a factor which has to be very seriously reckoned with. There has been much both of exaggeration and of understatement current upon the subject. It so happens that many of the most interesting sites in Greece are in localities notoriously unhealthy —Pylos and Thermopylæ are examples in point. Of the rare visitors to Pylos, two have died there since I was at the place in August, 1895; and of the population of about two hundred fisher-folk living near the lagoon in that year, not one was over the age of forty. The malaria fiend claims them in the end, and the end comes soon. At Thermopylæ, in this last summer, I escaped the fever, but caught ophthalmia in the marshes. An Englishman who was with me, and also our Greek servant, had bad attacks of fever.

On the whole, I prefer the spring as the season for work. The summer may be very hot. During the four weeks I was at Navarino the thermometer never fell below 93° Fahrenheit, night or day, and rose to 110° or 112° in the absolute darkness of a closed house at midday. What [ix]it was in the sun at this time, I do not know. I tried it with my thermometer, forgetting that it only registered to 140°, with disastrous results to the thermometer.

At Thermopylæ in 1899 the nights were, in July and August, invariably cool, though the heat at midday was very great; so much so that you could not, without using a glove, handle metal which had been exposed to it.

The winter is, I think, a bad time for exploration,—in Northern Greece at any rate. Rain and snow may make work impossible, and the mud on the tracks in the plain must be experienced in order to be appreciated. Snow, moreover, may render the passes untraversable.

To one who undertakes survey work in circumstances similar to those in which I have been placed, the expense of travelling in Greece is considerable. Survey instruments are cumbrous, if not heavy paraphernalia. Moreover, as I have been obliged to do the work within the limits of Oxford vacations, and as the journey to Greece absorbs much time, it has been necessary for me to labour at somewhat high pressure while in the country. Twelve hours’ work a day under a Greek sun, with four hours’ work besides, demands that the doer should be in the best of condition. One is therefore obliged to engage a servant to act as cook and purveyor, since the native food and cooking are not of a kind to support a Western European in a healthy bodily state for any length of time. In case of survey, moreover, it is just as well to choose a servant who knows personally some of the people of the district in which the work is carried on, as suspicions are much more easy to arouse than to allay, and original research may connect itself in the native mind with an increase of the land-tax.

There are very few parts of Greece where it is dangerous to travel without an escort. Since the recent war with Turkey, the North has been a little disturbed, and brigandage has never been quite stamped out in the Œta and Othrys region. But it is not the organized brigandage of old times; nor, I believe, in the vast majority of cases, are the crimes committed by the resident population. The Vlach shepherds, who come over from Turkish Epirus in [x]the summer with their flocks, are usually the offenders. Throughout nine-tenths of the area of the country an Englishman may travel with just as much personal security as in his own land.

The Greeks are a kindly, hospitable race. The Greek peasant is a gentleman; and, if you treat him as such, he will go far out of his way to help you. If you do not, there may be disagreeables.

I cannot acknowledge all the written sources of assistance to which I have had recourse in compiling this volume, because I cannot recall the whole of a course of reading which has extended over a period of ten years.

Of Greek histories I have used especially those of Curtius, Busolt, Grote and Holm; of editions of Herodotus those of Stein and Macan. Of special books, I have largely used the French edition of Maspero’s “Passing of the Empires,” and Rawlinson’s “Herodotus.” I have read Hauvette’s exhaustive work on “Hérodote, Historien des Guerres Médiques.” I have not, however, been able to use it largely, as I find that my method of dealing with the evidence differs very considerably from his.

Where I have consciously used special papers taken from learned serials, I have acknowledged them in the text.

Many of my conclusions on minor as well as major questions are founded on a fairly intimate knowledge of the theatre of war.1

I have dealt with the war as a whole, as well as with the major incidents of it, because it is a subject of great interest to one who, like myself, has, in the course of professional teaching, had to deal with the campaigns of modern times.

I cannot close this Preface without expressing my gratitude for the help which has been given me at various stages of my work.

Mr. Douglas Freshfield, himself a worker in historical research, and Mr. Scott Keltie gave me invaluable assistance at the time of my first visit to Greece, when I was holding the Oxford Travelling Studentship of the Royal Geographical Society.

[xi]My own college of Brasenose generously aided me with a grant in 1895, which was renewed last year.

In reckoning up the debt of gratitude, large items in it are due to my friends Mr. Pelham and Mr. Macan. As Professor of Ancient History, Mr. Pelham is ever ready to aid and encourage those who are willing to work in his department, and I am only one of many whom he has thus assisted. Such grants as I have obtained from the Craven Fund have been obtained by his advocacy, and he has often by his kindly encouragement cheered the despondency of a worker whose work can only be rewarded by the satisfaction of having done it,—a reward of which he is at times, when malarial fever is upon him, inclined to under-estimate the value.

I owe much to that personal help which Mr. Macan so kindly gives to younger workers in the same field as his own. He has also been kind enough to read through the first three chapters of this book. Though he has suggested certain amendments which I have adopted, he is in no way responsible for the conclusions at which I have arrived.

To Canon Church, of Wells, I am deeply indebted for those illustrations which have been made from the beautiful collection of Edward Lear’s water-colour sketches of Greece which he possesses.

My father, George Frederick Grundy, Vicar of Aspull, Lancashire, has read through all my proofs, and has done his best to make the rough places smooth. I have every reason to be grateful for this labour undertaken with fatherly love, and, I may add, with parental candour.

The chapters in this volume which deal with the warfare of 480–479 were awarded the Conington Prize at Oxford, given in the year 1900.

G. B. GRUNDY.

Brasenose College, Oxford,

October, 1901.

[xii]

NOTE.

Note.—After nearly a year spent in learning the principles and practice of surveying, I went to Greece in the winter of 1892–93, and made

- A survey of the field of Platæa;

- A survey of the town of Platæa;

- A survey of the field of Leuctra.

I also examined

- The western passes of the Kithæron range;

- The roads leading to them from Attica by way of Eleusis and Phyle respectively;

- The great route from Thebes northward, west of Kopais, as far as Lebadeia and Orchomenos.

In the summer of 1895 I revisited Greece.

During that visit I did the following work:—

- A survey of Pylos and Sphakteria;

- An examination of the great military route from Corinth to Argos, and from Argos, by way of Hysiæ, to Tegea;

- An examination of the military ways from the Arcadian plain into the Eurotas valley;

- I also followed and examined the great route from the Arcadian plain to Megalopolis, and thence to the Messenian plain;

- An examination of the site of Ithome.

In the recent summer of 1899 I did further work abroad in reference to Greek as well as Roman history. The Greek portion consisted of:—

- A visit to the site of and museums of Carthage, with a view to ascertaining the traceable effects of Greek trade and Greek influence in the Phœnician city;

- A detailed examination, lasting ten days, of the region and site of Syracuse;

- An examination of the field of Marathon, which I had previously visited, though under adverse circumstances of weather, in January, 1893;

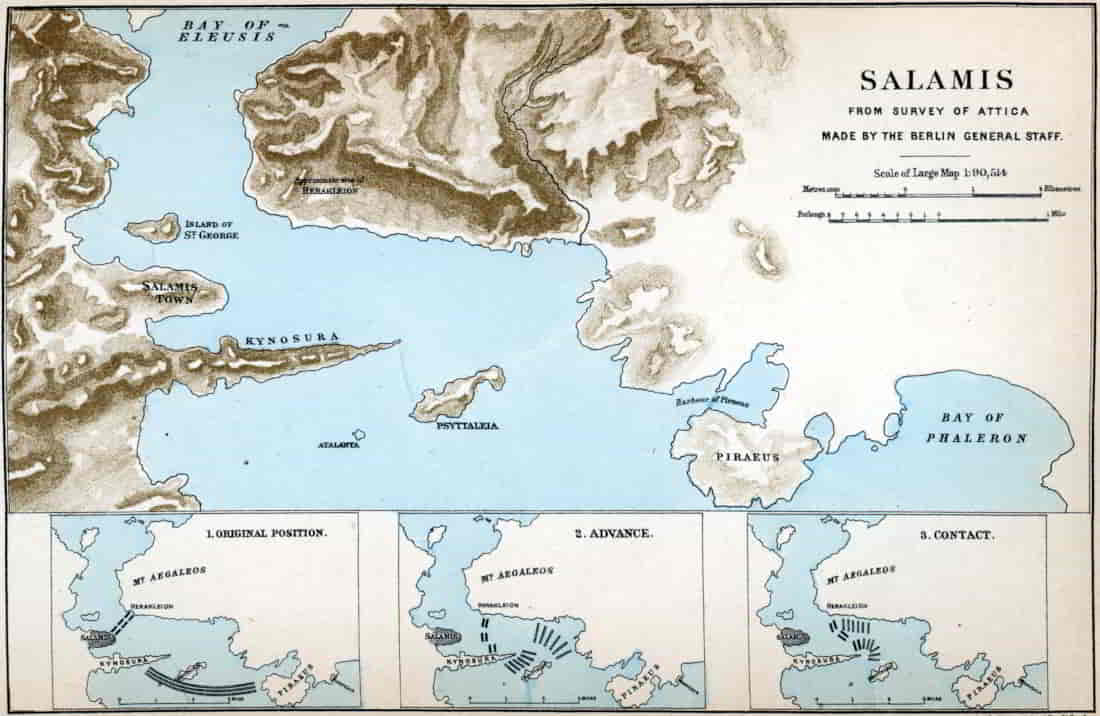

- A very careful examination of Salamis strait;

- A voyage up the Euripus, and such examination of the strait at Artemisium as was necessary;

- A survey of the pass of Thermopylæ;

- A detailed examination of the path of the Anopæa;

- An examination of the Asopos ravine and the site and neighbourhood of Heraklea Trachinia;

- An examination of the route southward from Thermopylæ, through the Dorian plain, past Kytinion and Amphissa to Delphi;

- A second examination of Platæa and the passes of Kithæron.

Other parts of Greece known to me, though not visited with the intention of, or, it may be, under circumstances permitting, historical inquiry are:—

- Thessaly, going

- (a) From Volo to Thaumaki, viâ Pharsalos;

- (b) From Volo to Kalabaka (Æginion) and the pass of Lakmon;

- (c) From Volo to Tempe, viâ Larissa;

- The great route from Delphi to Lebadeia by the Schiste;

- The route up the west coast of Peloponnese from Pylos, through Triphylia and Elis to Patras;

- The neighbourhood of Missolonghi;

- Corfu and Thera (Santorin).

CONTENTS.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Greek and Persian | 1 |

| II. | Persian and Greek in Asia. The Scythian Expedition | 29 |

| III. | The Ionian Revolt | 79 |

| IV. | Persian Operations in Europe: b.c. 493–490. Marathon | 145 |

| V. | The Entr’acte: b.c. 490–480 | 195 |

| VI. | The March of the Persian Army. Preparations in Greece | 213 |

| VII. | Thermopylæ | 257 |

| VIII. | Artemisium | 318 |

| IX. | Salamis | 344 |

| X. | From Salamis to Platæa | 408 |

| XI. | The Campaign of Platæa | 436 |

| XII. | Mykale and Sestos | 522 |

| XIII. | The War as a Whole | 534 |

| XIV. | Herodotus as the Historian of the Great War | 556 |

| INDEX | 581 | |

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS.

| TO FACE PAGE | |

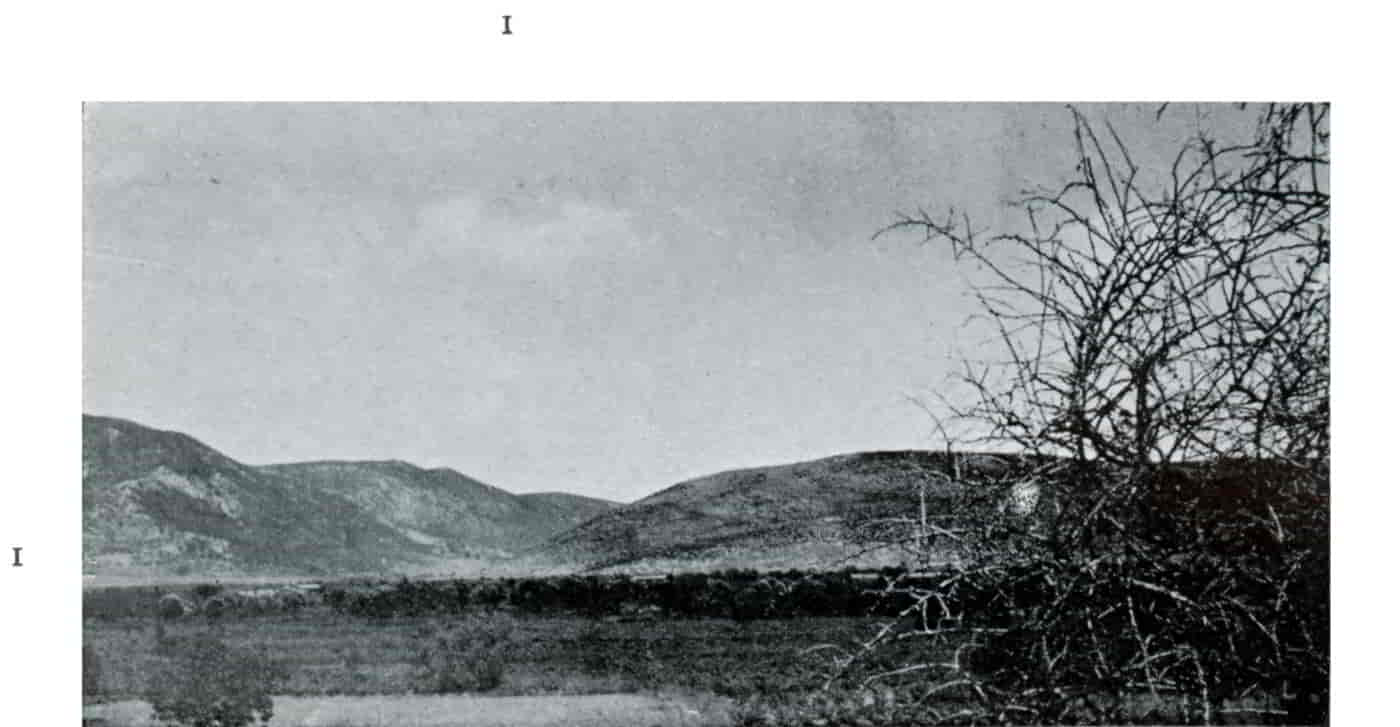

| Marathon: from the “Soros,” looking towards Little Marsh | 163 |

| The “Soros” at Marathon | 165 |

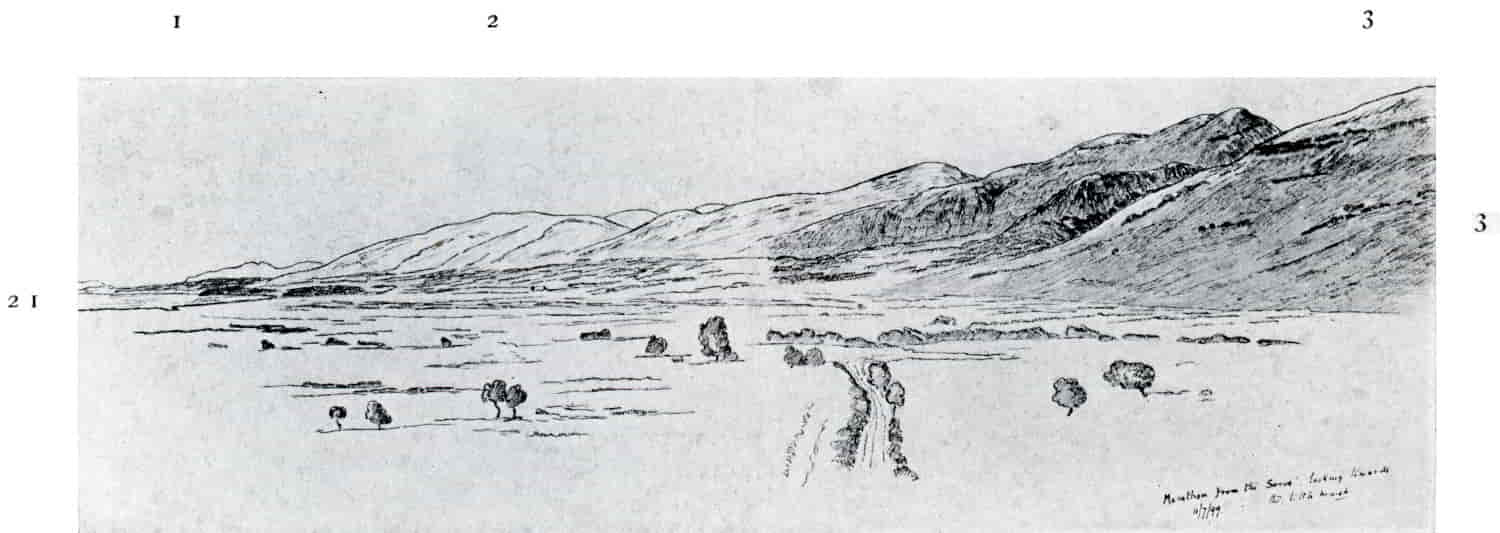

| Marathon from the “Soros” | 187 |

| The Vale of Tempe | 231 |

| The Harbour of Corcyra | 241 |

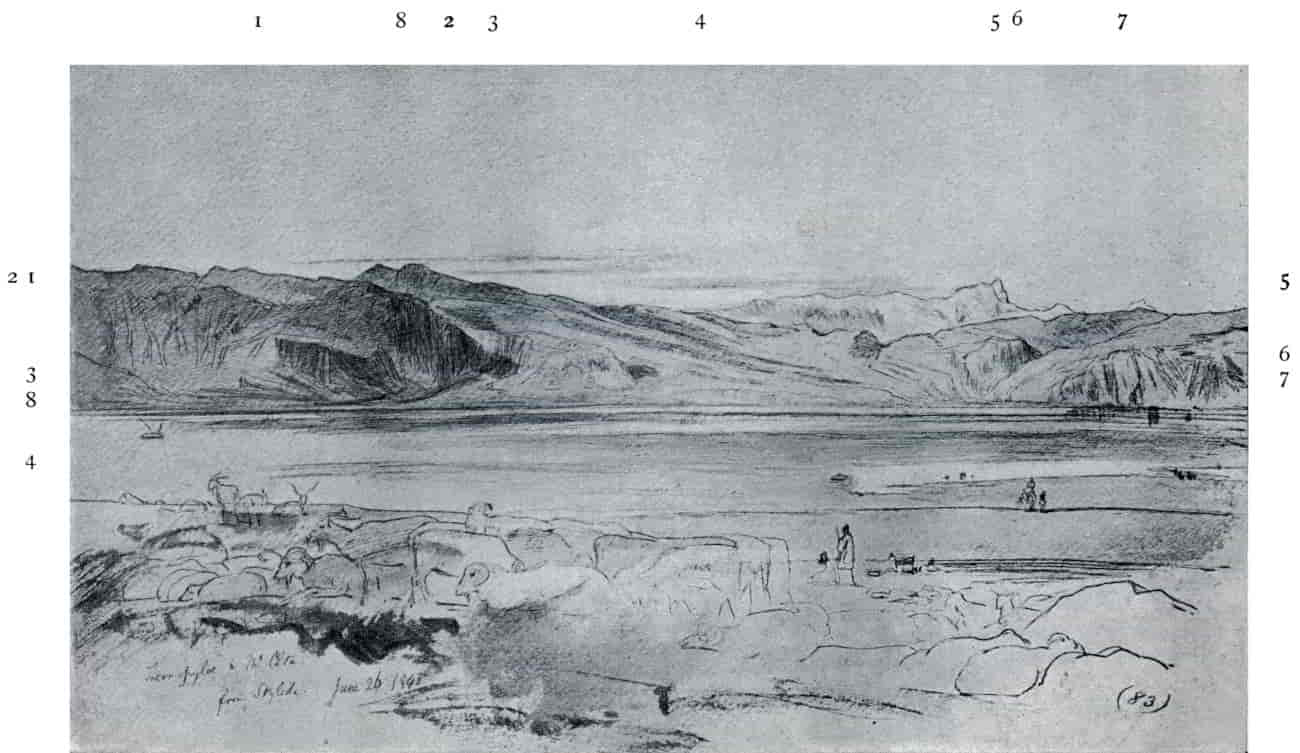

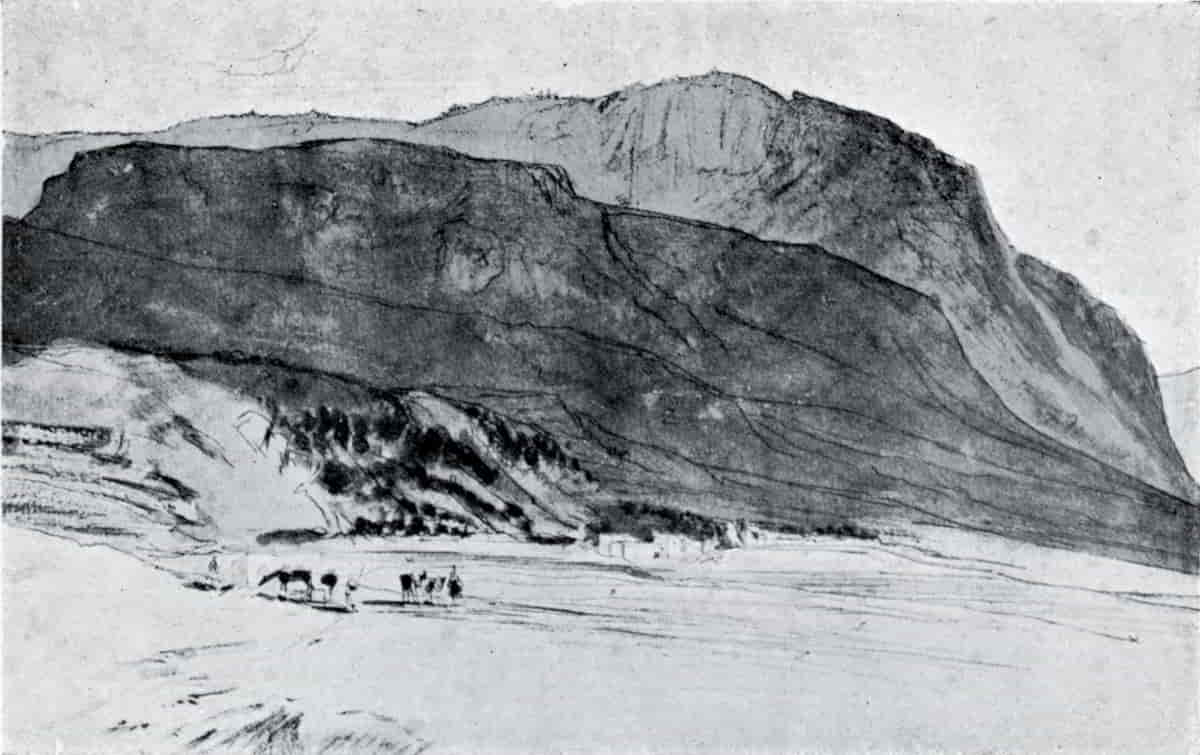

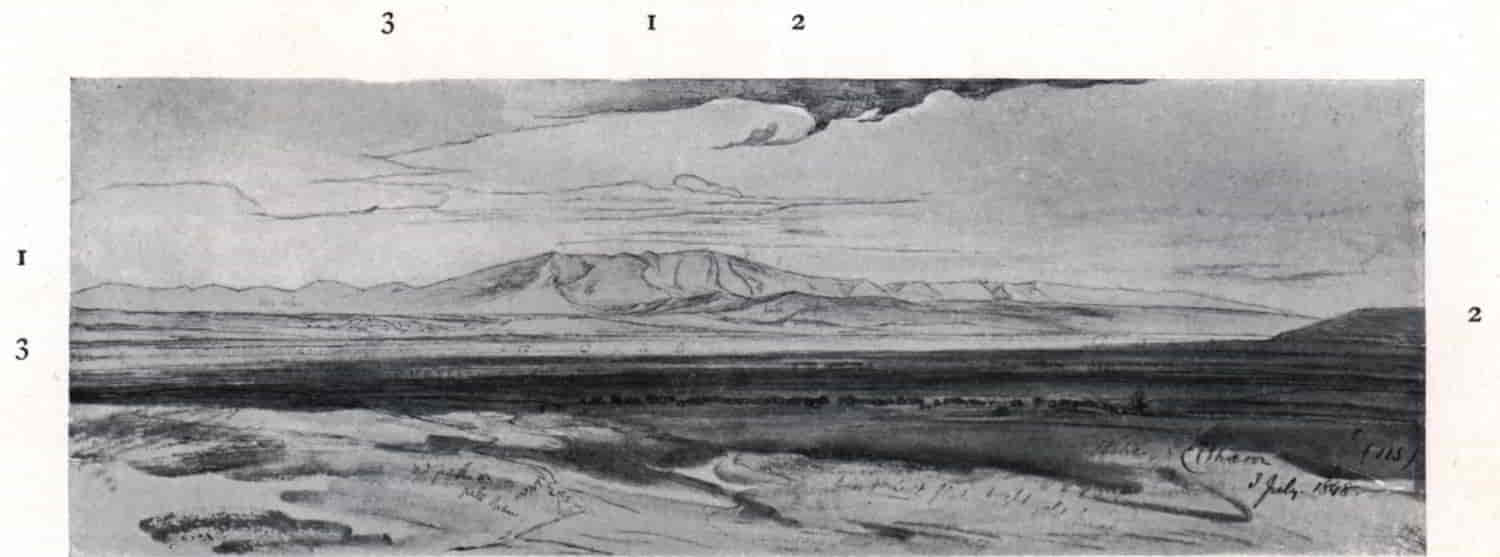

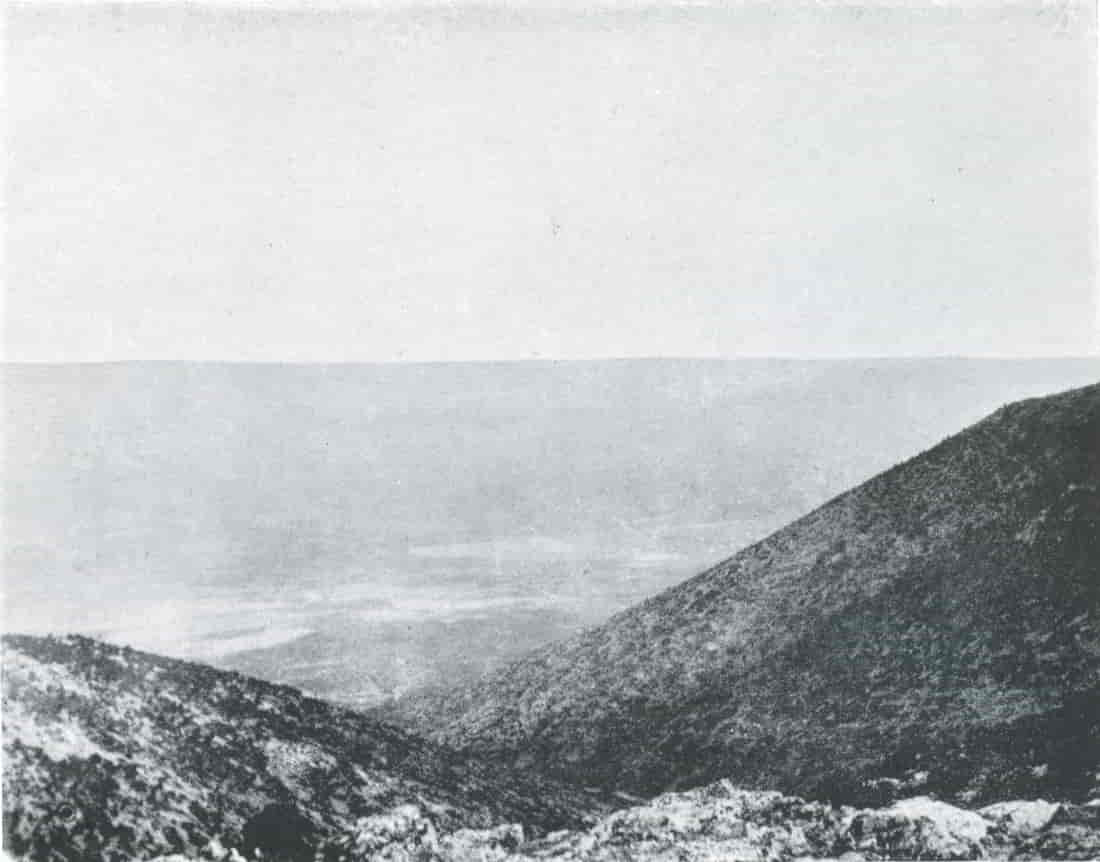

| Mountains of Thermopylæ, from Phalara | 257 |

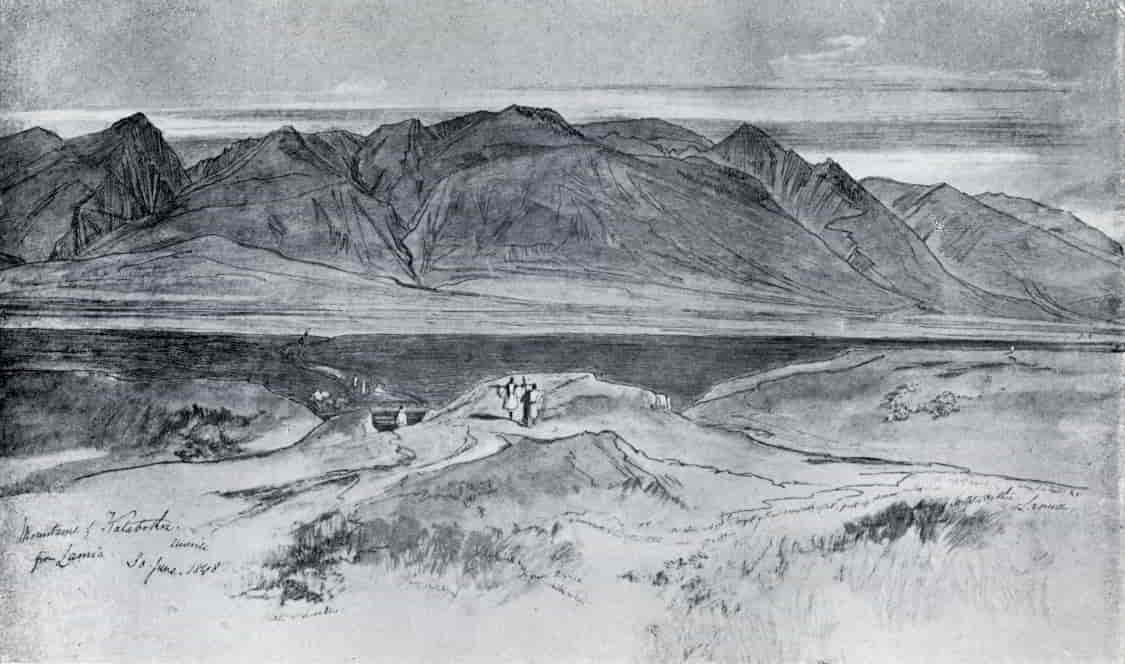

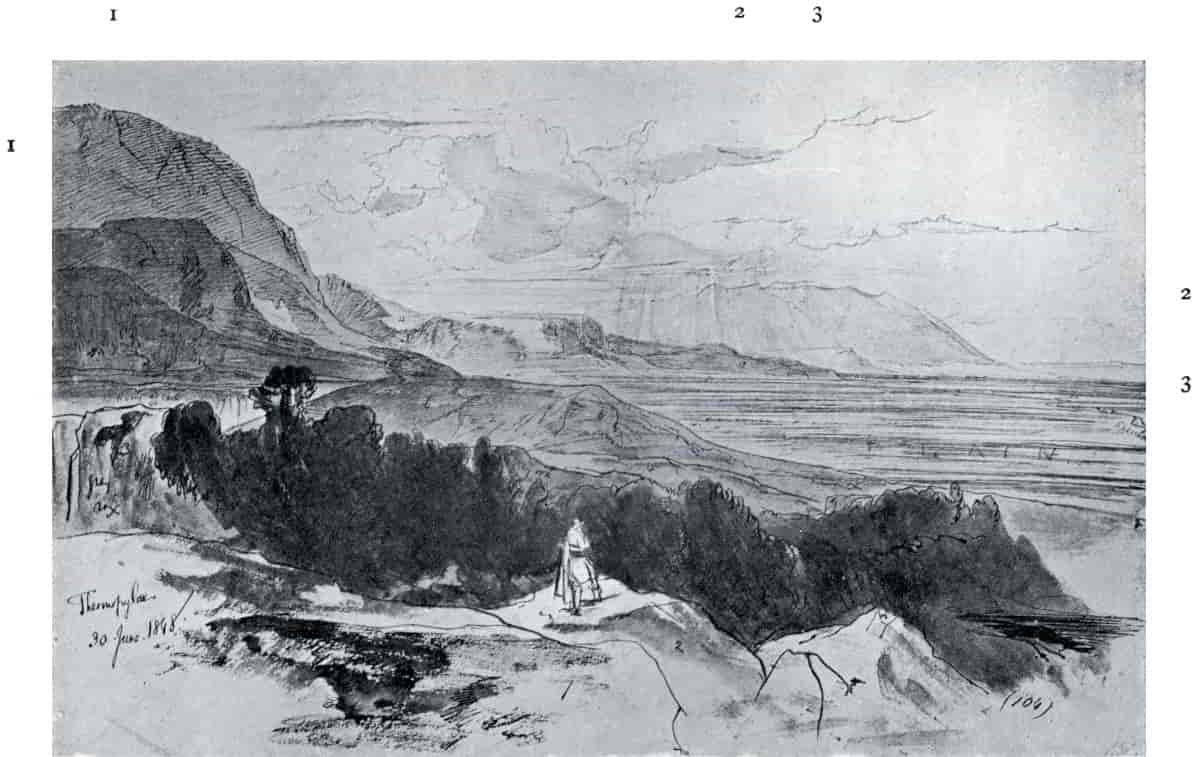

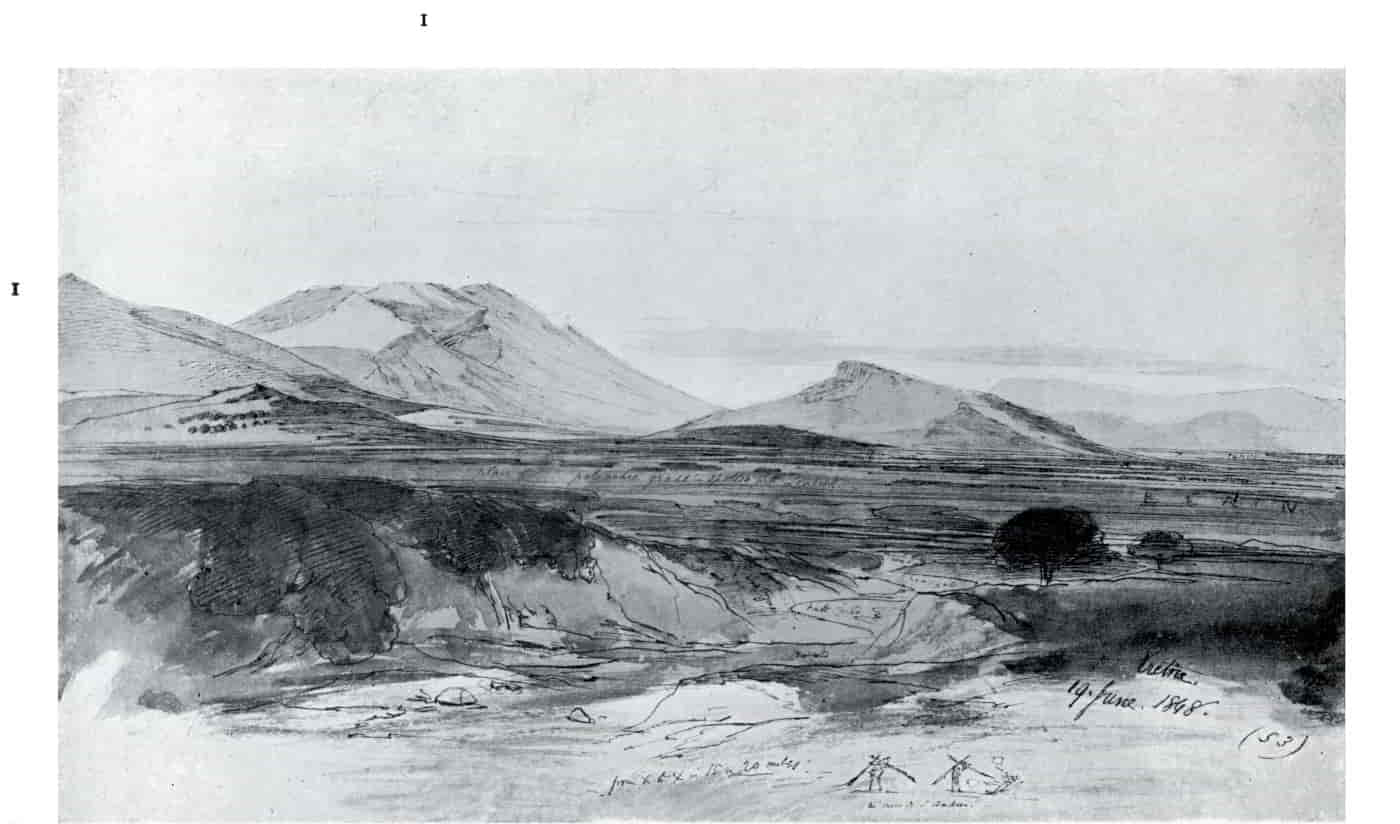

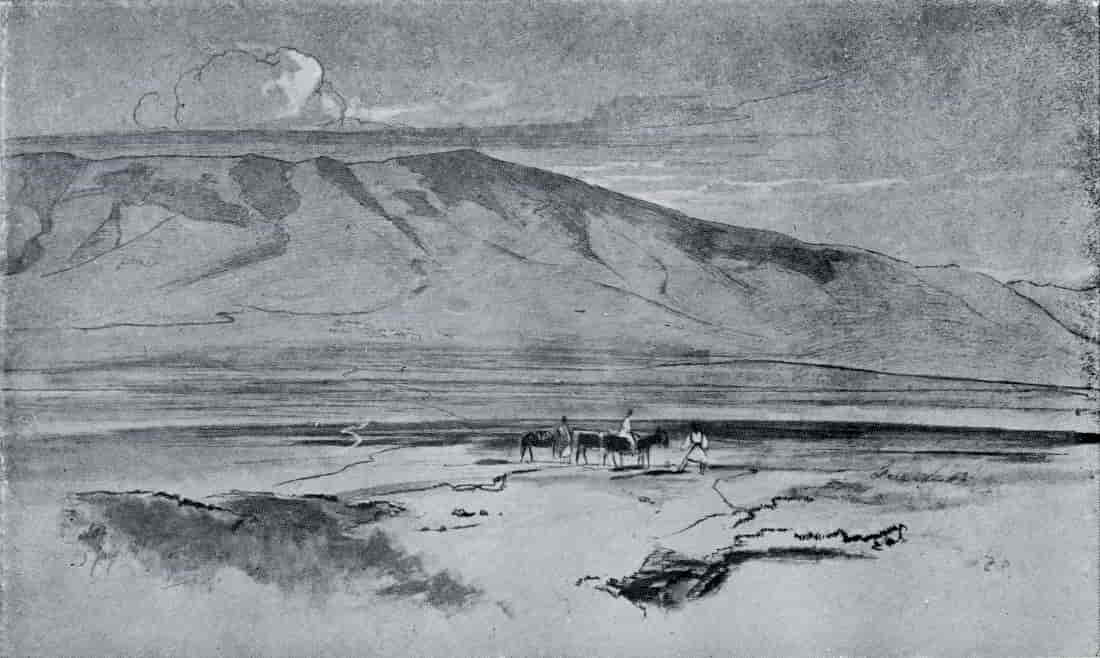

| Mount Œta and Plain of Malis | 259 |

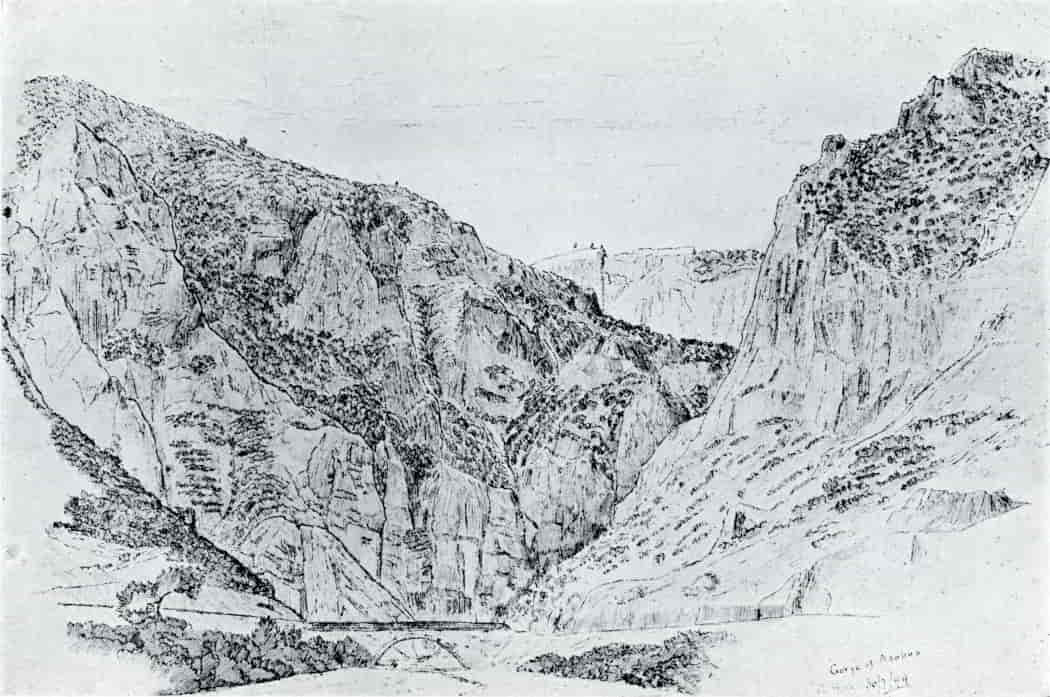

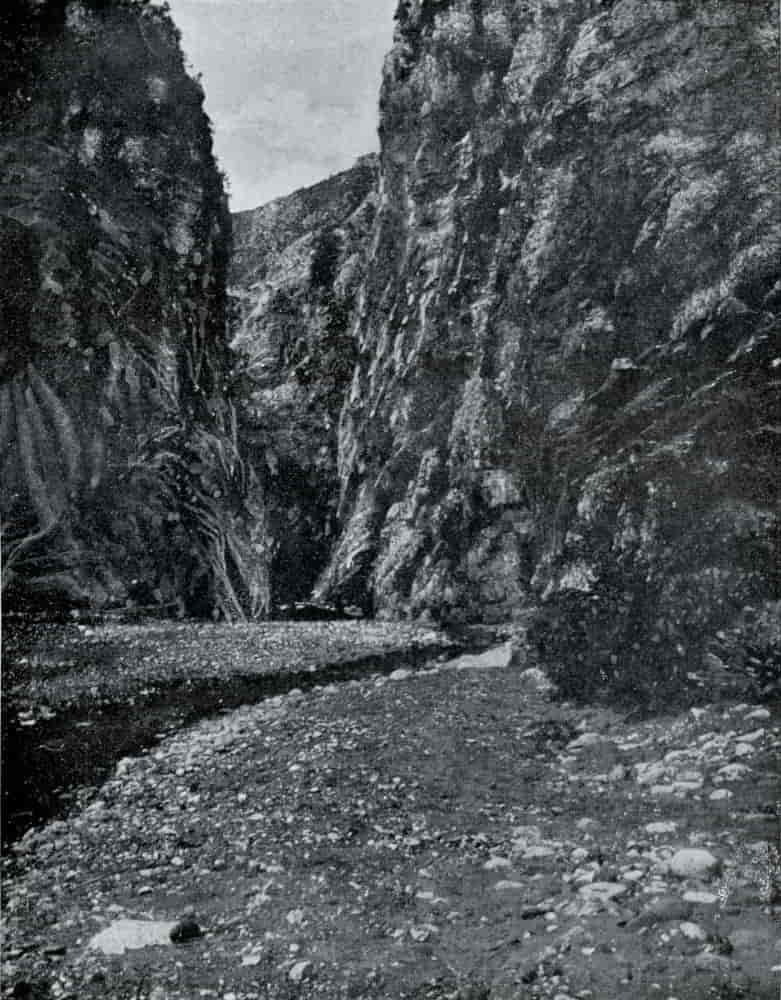

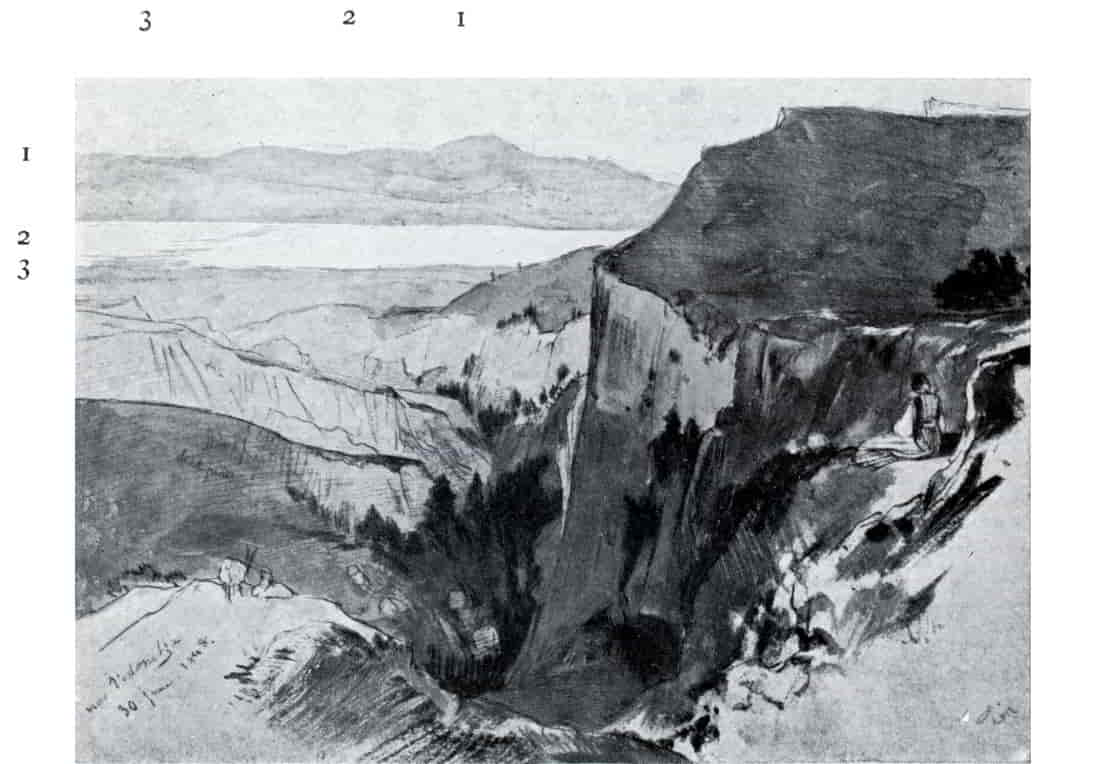

| Asopos Ravine | 261 |

| The Gorge of the Asopos | 261 |

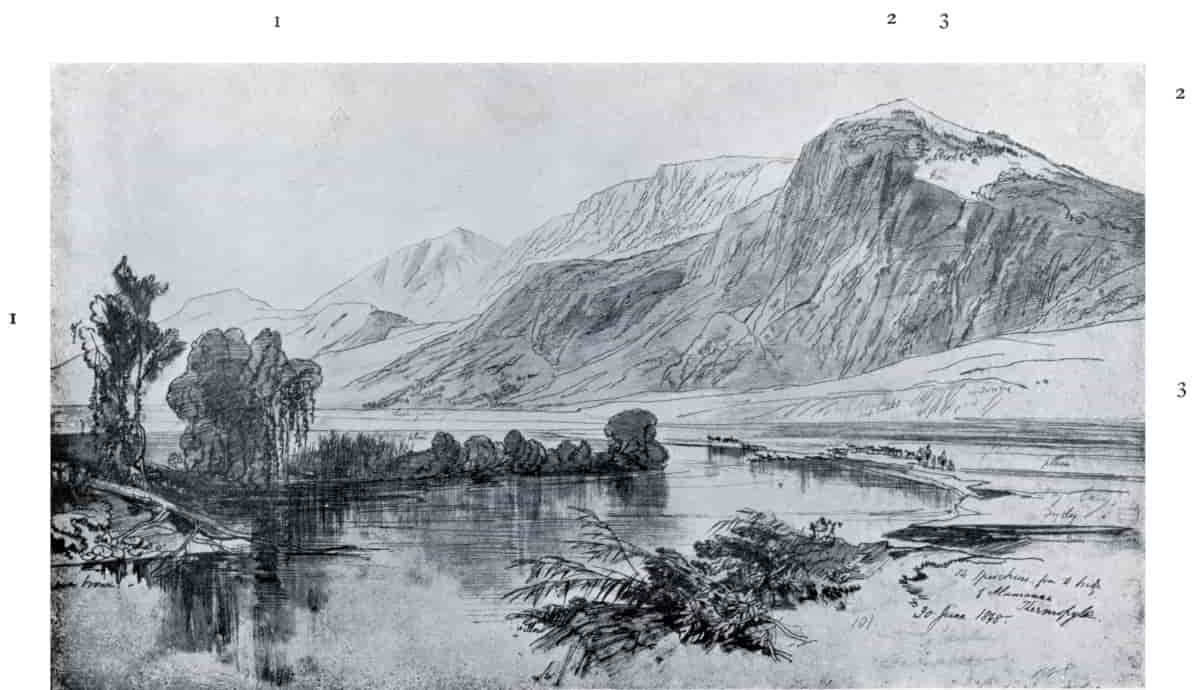

| Thermopylæ, from Bridge of Alamana | 263 |

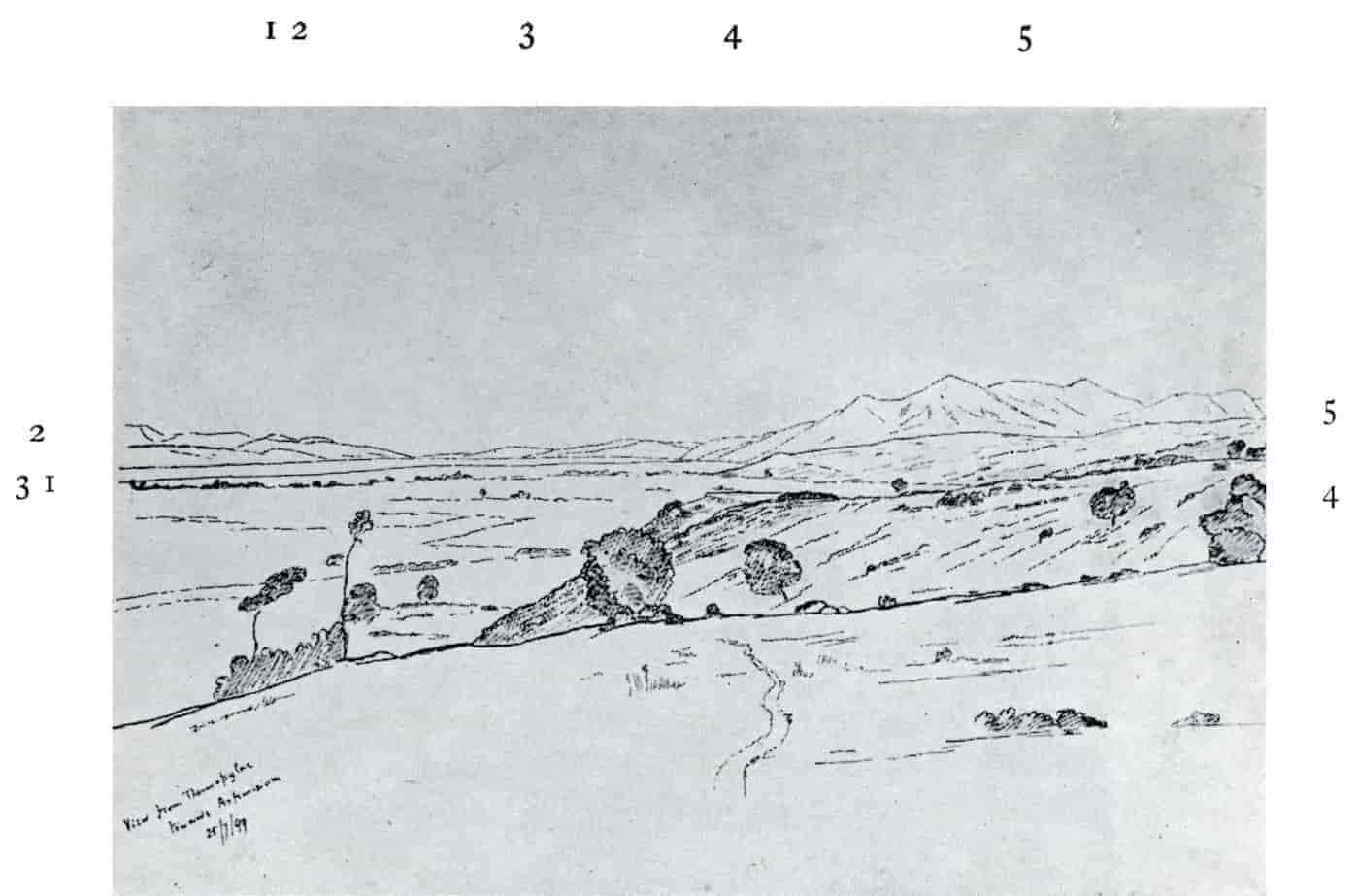

| View from Thermopylæ, looking towards Artemisium | 264 |

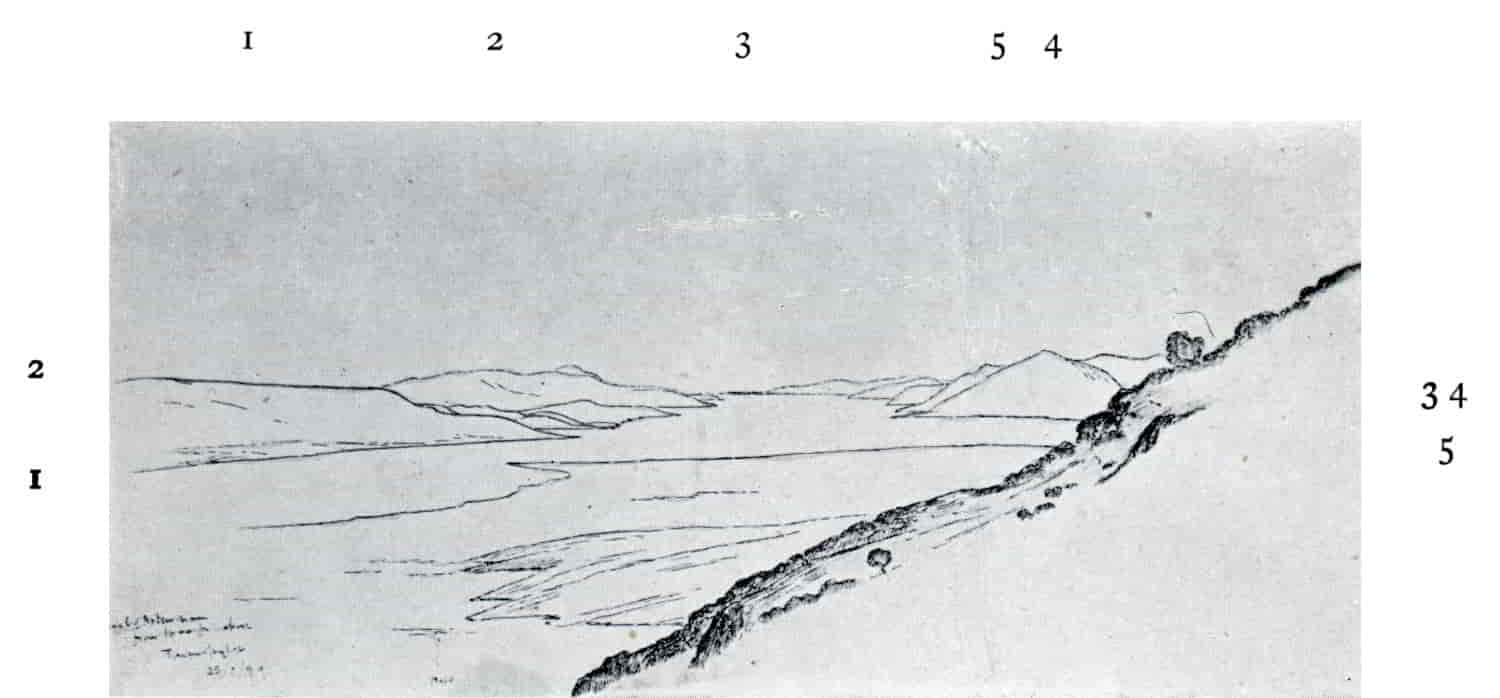

| Channel of Artemisium, from 1600 Feet above Thermopylæ | 264 |

| On Thermopylæ-Elatæa Road (viâ Modern Boudenitza) | 265 |

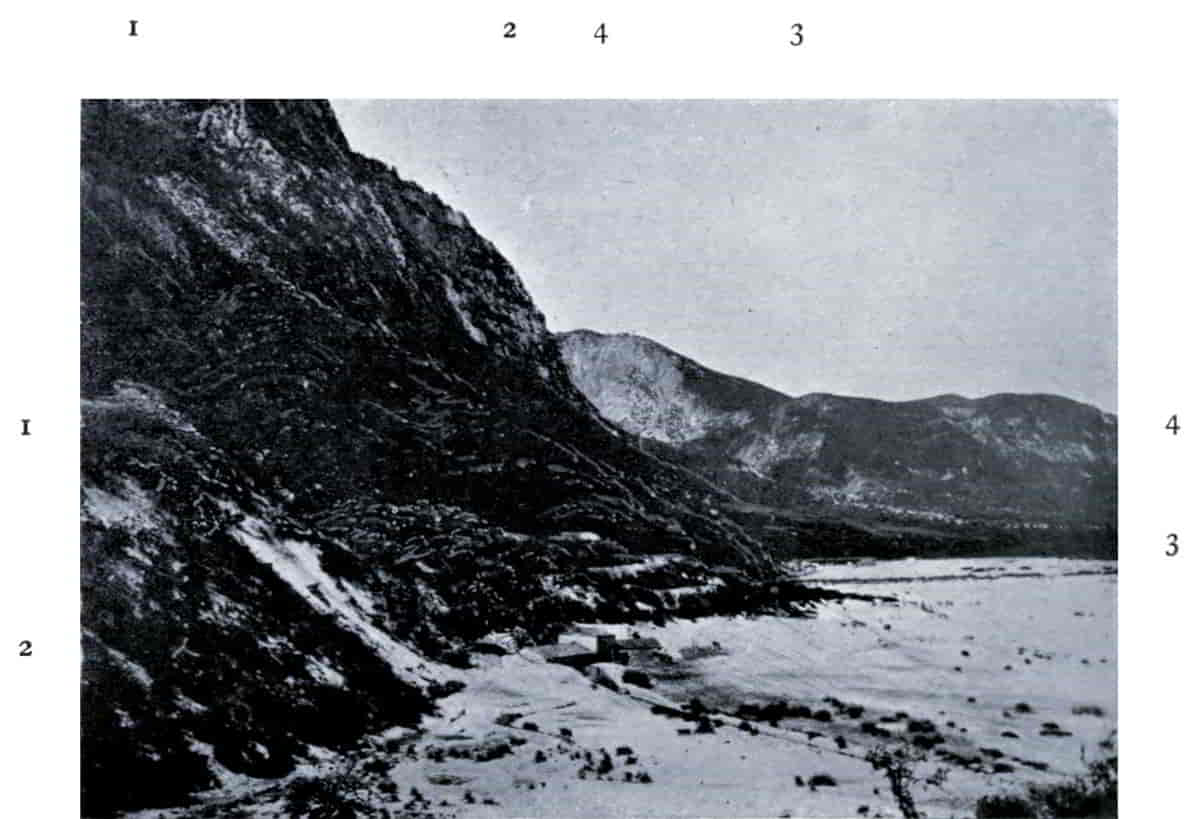

| Thermopylæ between Middle and East Gate | 290 |

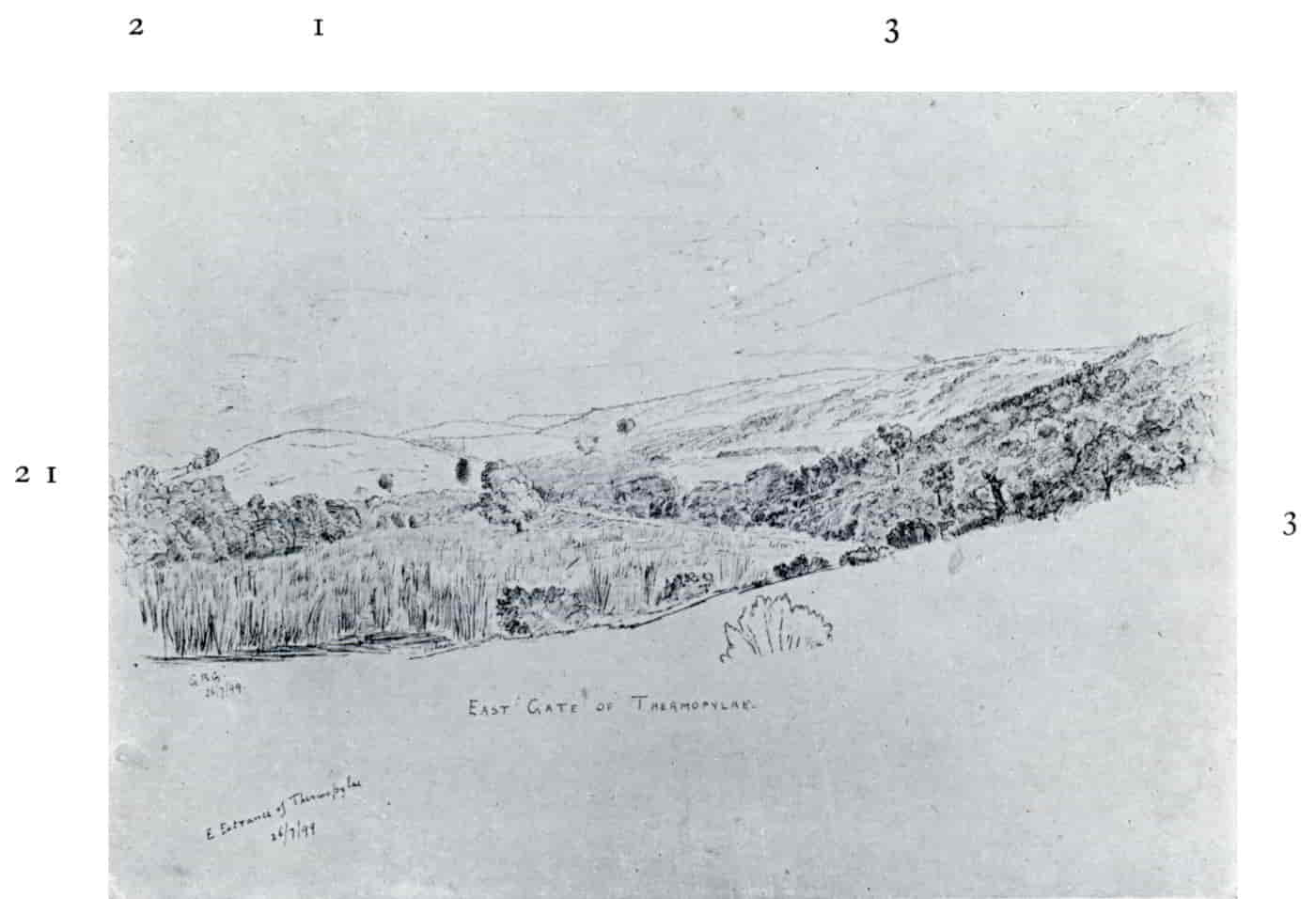

| The East Gate of Thermopylæ | 291 |

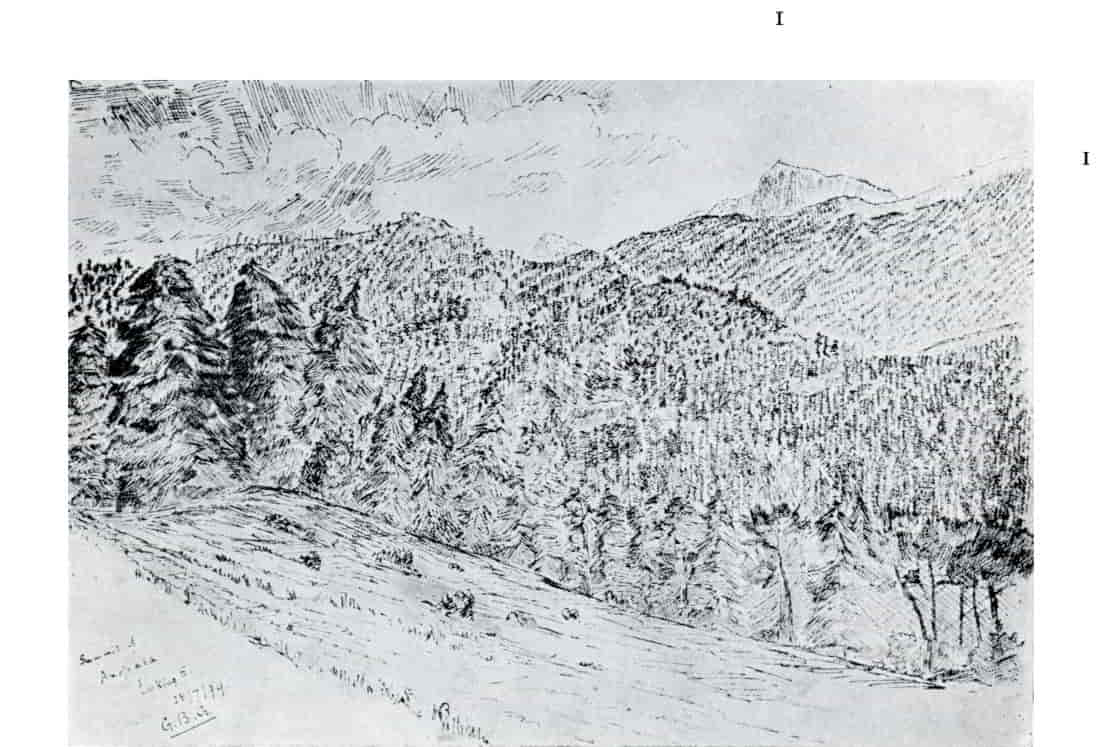

| Summit of Anopæa, looking East | 301 |

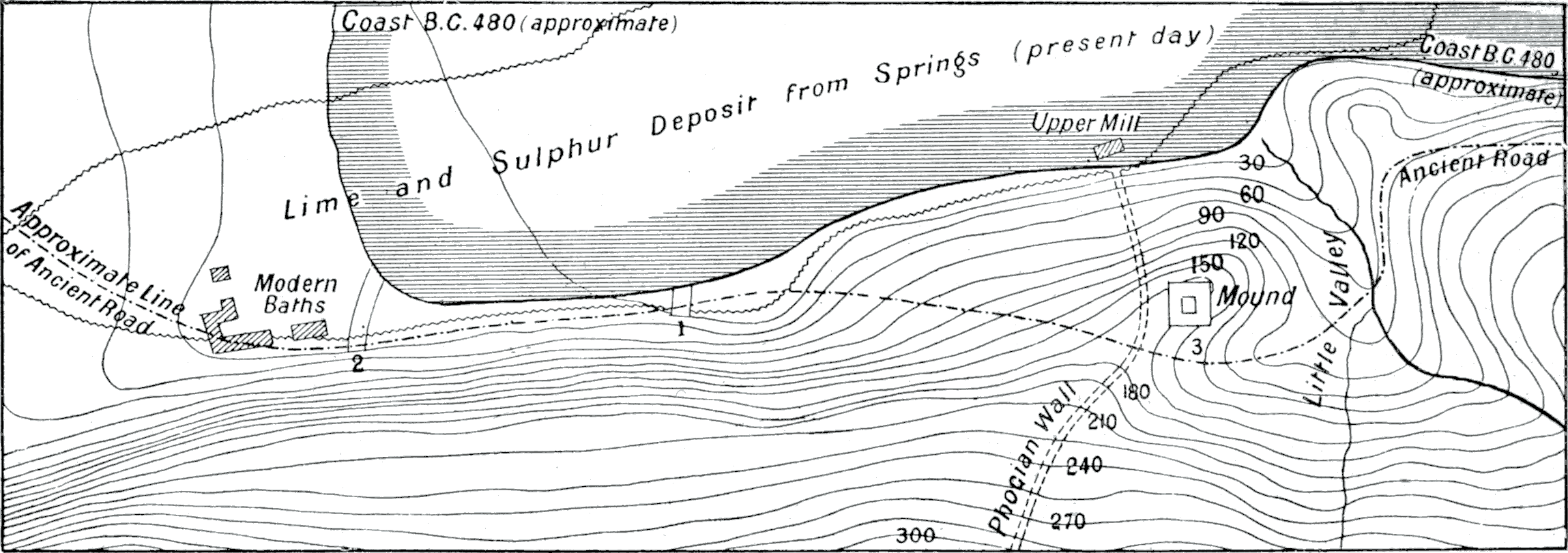

| Coast at Middle Gate of Thermopylæ in 480 | 310 |

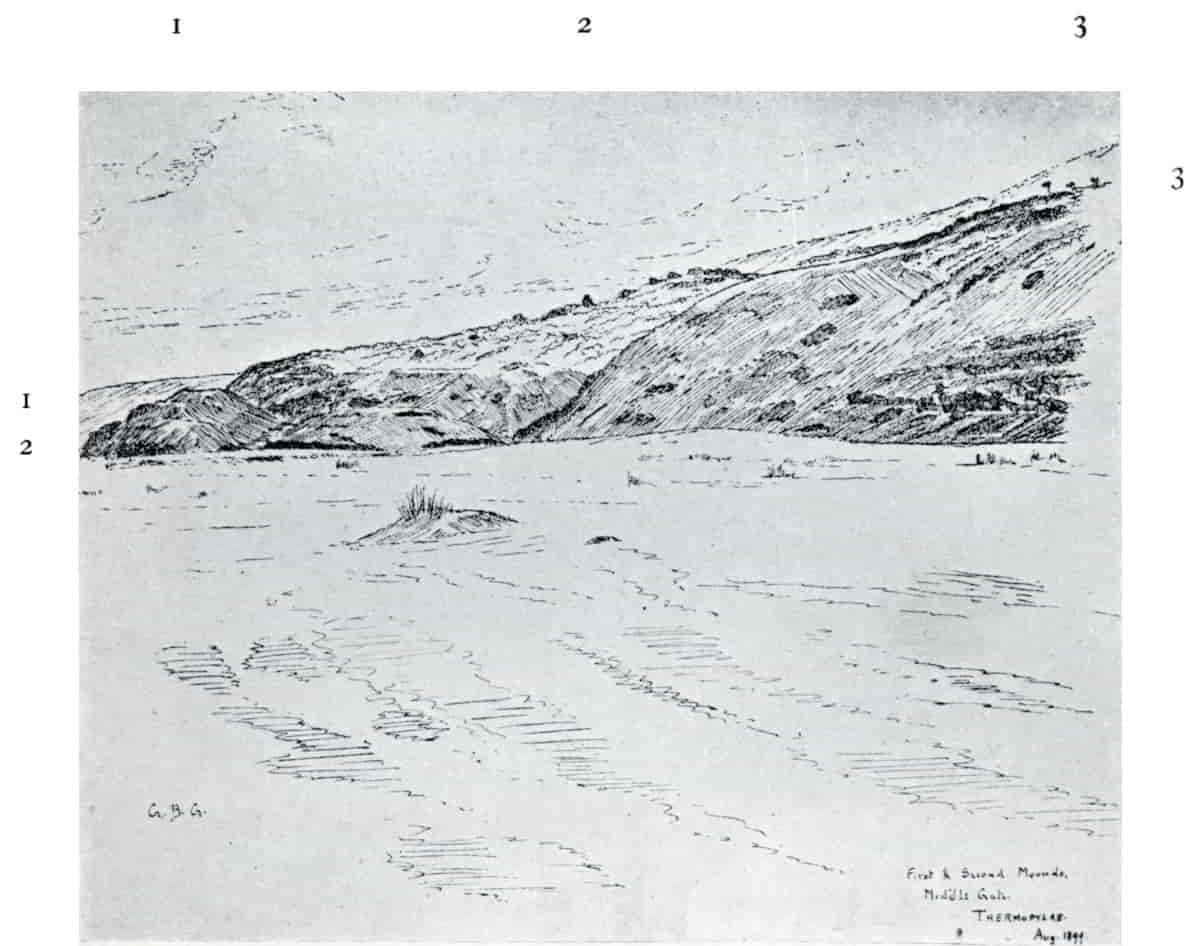

| Thermopylæ | 311 |

| Thermopylæ: the Middle Gate | 311 |

| First and Second Mounds, Middle Gate, Thermopylæ | 312 |

| Plain of Eubœa | 321 |

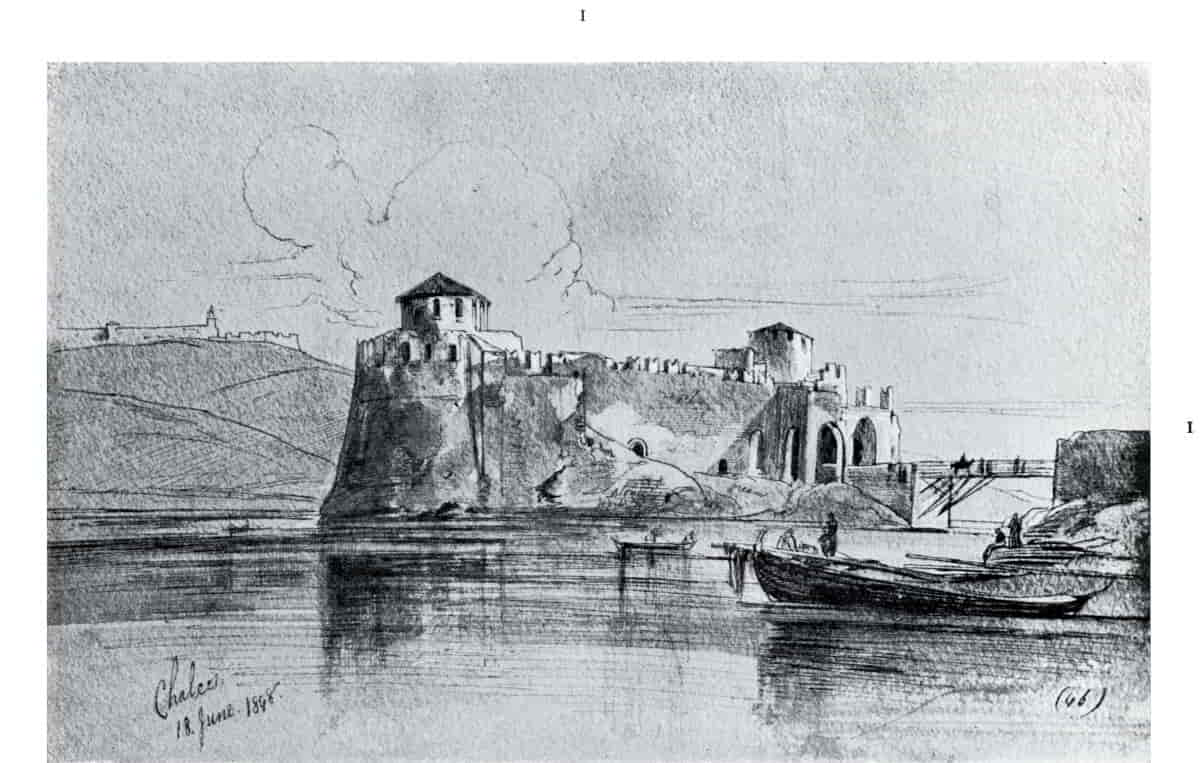

| The Narrows at Chalkis | 323 |

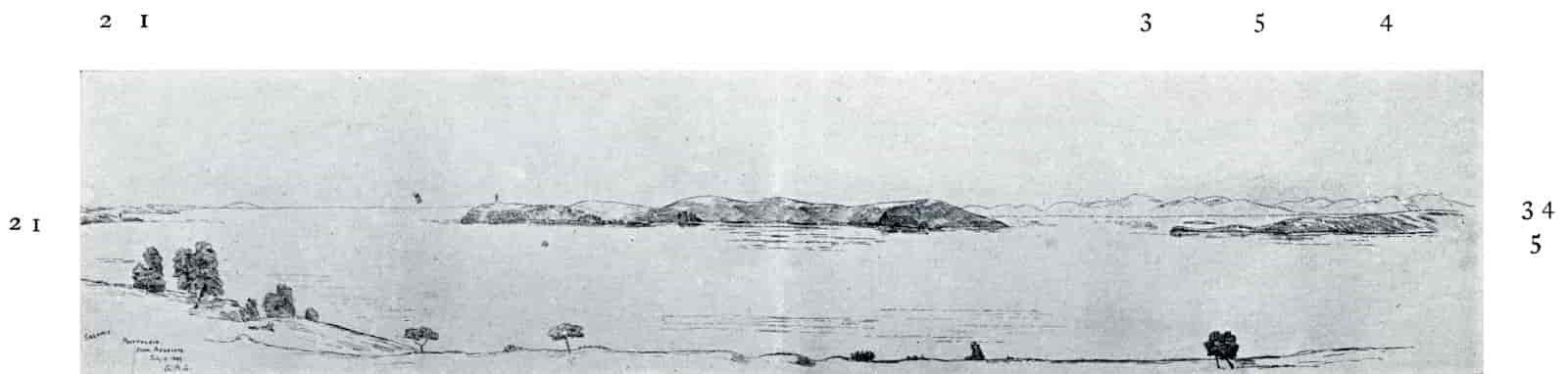

| Salamis, looking South from Mount Ægaleos, with the Island of Psyttaleia in the Centre | 392 |

| Plain of Thebes and Mount Kithæron | 436 |

| Plain of Kopais, from Thebes | 452 |

| Plain of Platæa and Kithæron | 454 |

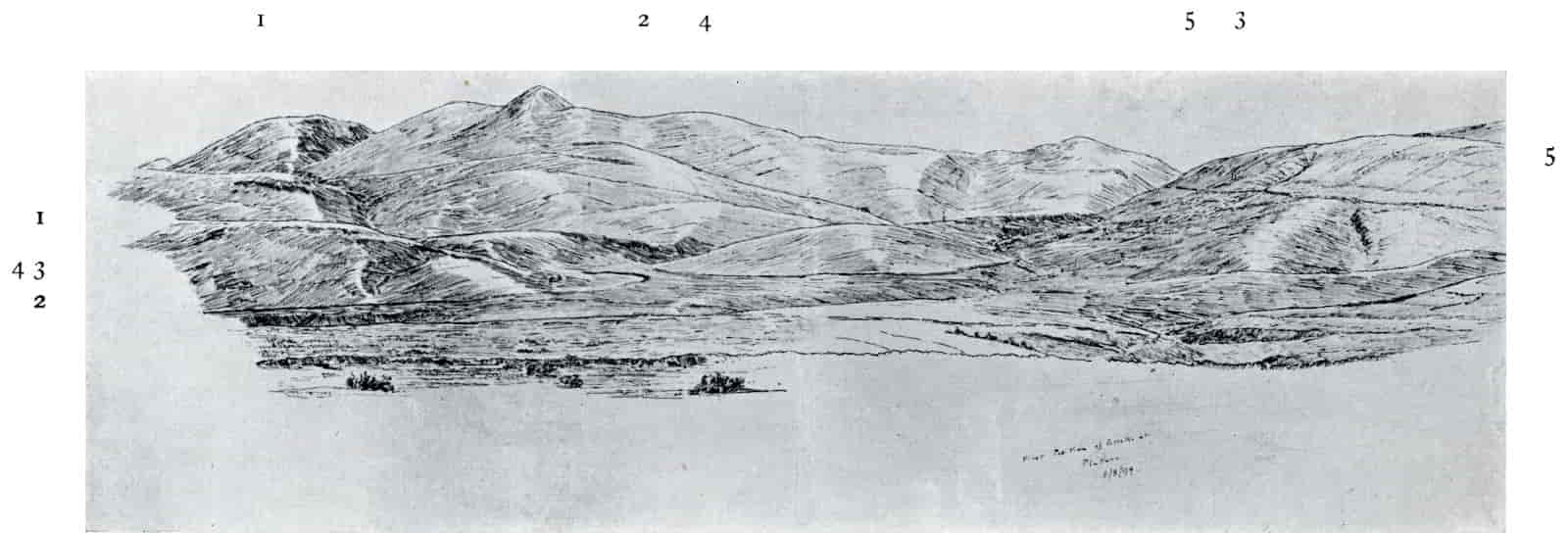

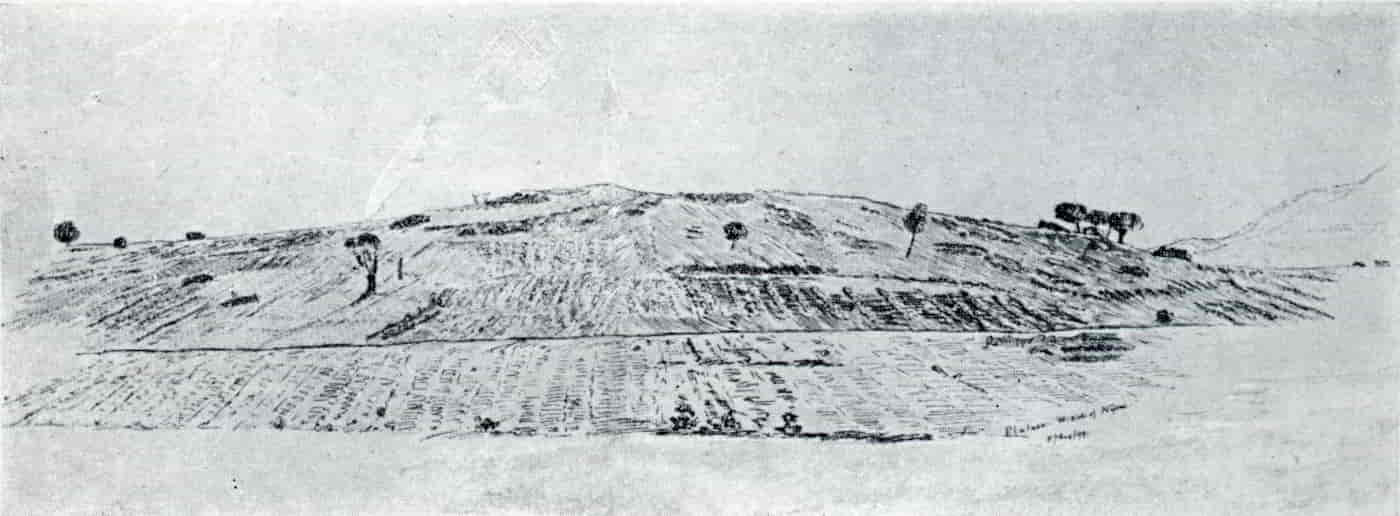

| The First Position at Platæa | 460 |

| Platæa: “Island,” from Side of Kithæron | 480 |

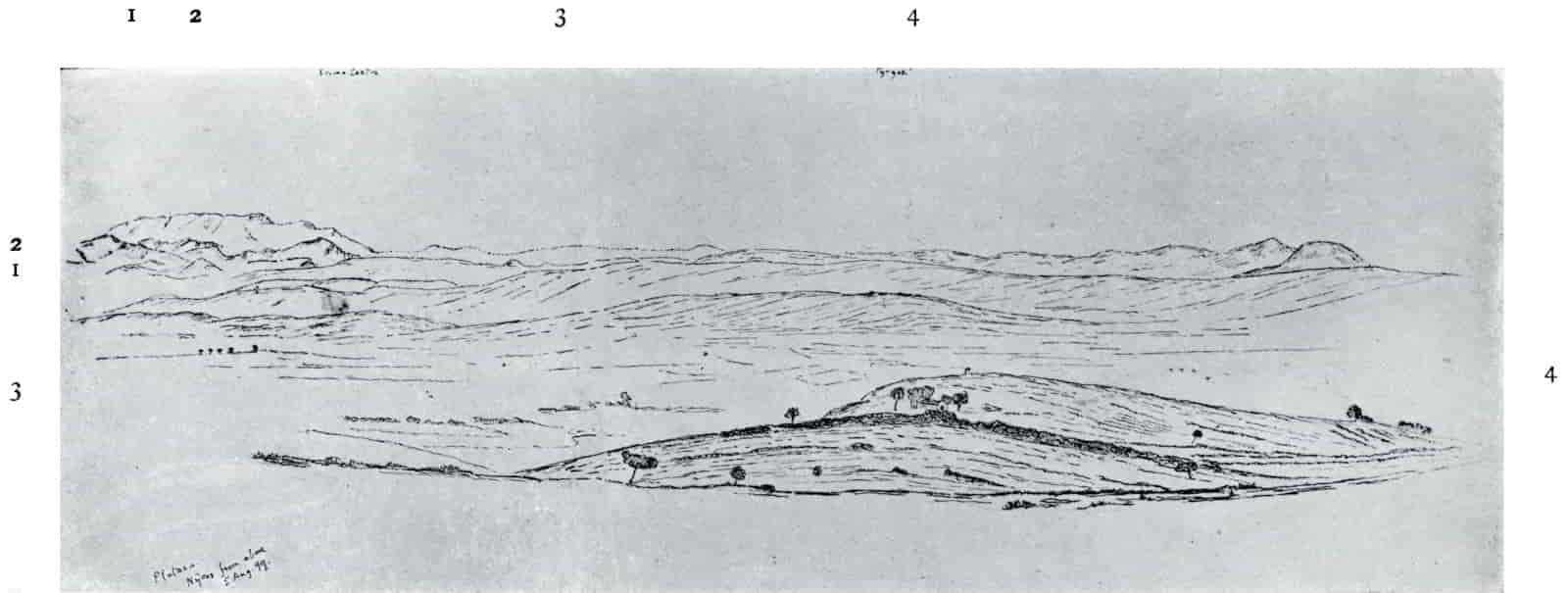

| Bœotian Plain, from Platæa-Megara Pass | 482 |

| Platæa—West Side of Νῆσος | 482 |

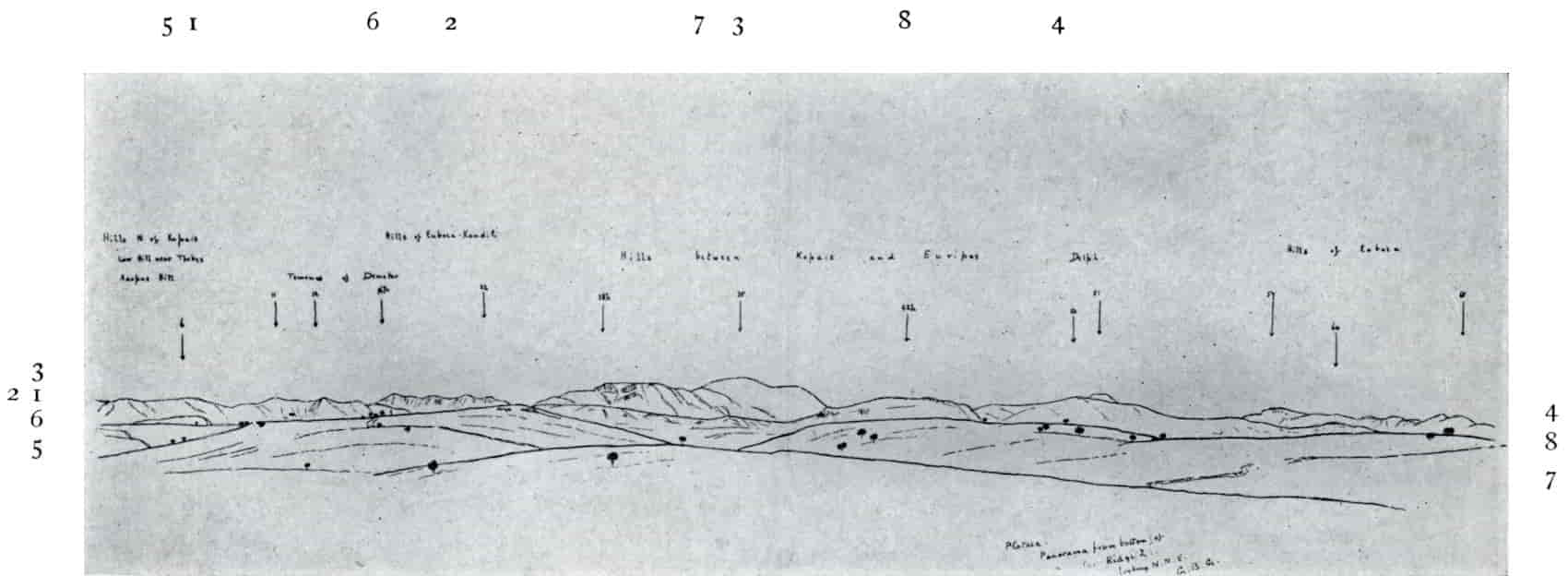

| Platæa: Panorama from Scene of Last Fight | 502 |

MAPS.

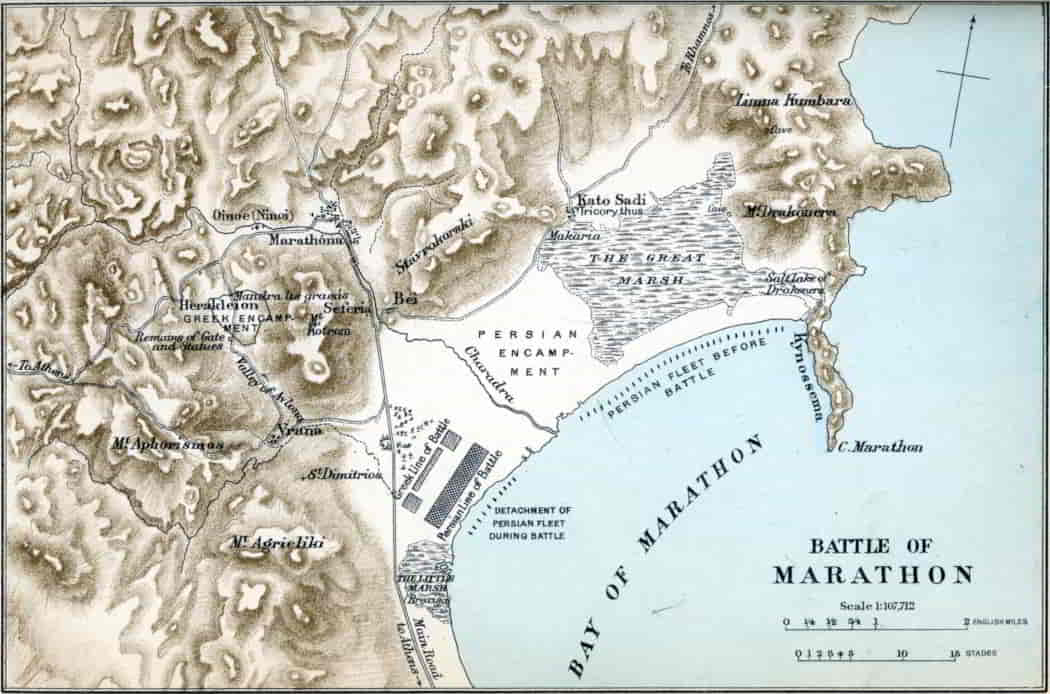

| Battle of Marathon | 166 |

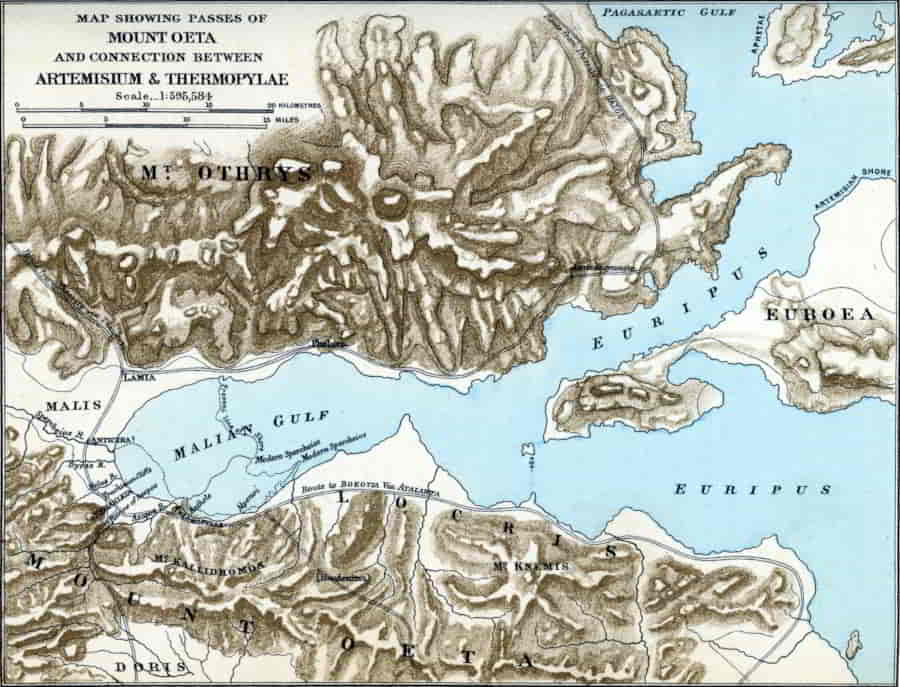

| Region of Thermopylæ and Malian Gulf | 266 |

| Isthmus of Corinth and West Attica | 368 |

| Salamis | 384 |

| Thermopylæ | At end |

| Platæa | At end |

[1]

CHAPTER I.

GREEK AND PERSIAN.

The sharp, fierce struggle between Greek and Persian which was fought out on land and sea in the years 480–479, was regarded by those who were contemporary with it, and has ever since been looked upon as the great crisis in the history of the two races. It was a struggle whose results were decisive in the history of the world. From a purely military point of view, it is true, the fighting in those two years was not final. The loser did not issue from it in a condition so crippled that he could not continue the contest. So far from this being the case, Persia, for more than a century after Salamis was fought, continued not merely to show a bold front to Greece, but to maintain the preponderance of her power in the lands east of the Ægean, and to be a cause of dread to the Hellene of Europe. Athens did, in the period succeeding these great years of the war, wrest from Persia most of the Hellenic or semi-Hellenic Islands and coast towns in the Eastern Ægean; but her tenure of many of them was brief, and of all, precarious. The city States on the mainland slip rapidly from her grasp, and the measure of the independence from Persia in the case of some of those who remain on the tribute lists is at least open to discussion. It was long before the Greek world discovered that decay of the great Empire which is so apparent to the student of history who has the story of the fifth and [2]fourth centuries before him. It set in soon after 479; but how far it was caused by the festering of the wounds inflicted in that year cannot now be said. The mischief was internal: it was situate far away in the depths of Asia, beyond the ken of the Greek of the fifth century, and it is not strange that he never appreciated the full extent of the malady.

And yet there is even a military point of view, from which the warfare of these years was, in a sense, decisive. From that time forward Persia was the assailed and not the assailant. The Great King either was not, or did not feel himself in a position to assume the offensive beyond the waters which separated Asia from Europe.

In reckoning up the results of a great war it is instructive to appreciate what was: it is impossible to ignore what might have been. Of the issues, military, political, and social, of this Græco-Persian war, the military issue is perhaps the least important from the point of view of world-history. It did, indeed, teach a great lesson, in that it brought into prominence for the first time the strength and weakness of the East and West when brought into contact with one another; but the most extraordinary feature about this special aspect of the matter is that those who had tried the tremendous experiment were all but utterly unconscious of the true bearing of its results; and it was left to the fourth generation from them to appreciate a truth which their forefathers had proved but never realized.

The possible results from a political and social point of view which might have ensued, had the war ended otherwise than it did, have formed the subject of many a surmise for those who have written the history of these years. If Herodotus can be taken as representative of the views and sentiments of men of his time,—the men, that is to say, of the half century which succeeded the critical phase of the long warfare with Persia,—it is evident that those who regarded the great series of events from a near perspective were supremely conscious of the political, and but little, if at all, conscious of the social issue. THE ISSUES AT STAKE IN THE WAR. It was perhaps the very intensity of the love of [3]freedom with the Greek that blinded him to all save the fact of the preservation of that freedom. Doubtless that feeling was largely bound up with the social question of the preservation of Hellenic civilization, and with the consciousness of the peril to which any social system must be exposed under a political system alien to it. It is nevertheless strange that, if the peril had been regarded in this instance as a very real one, a historian like Herodotus, whose wide experience of other social systems seems to have had the effect of making him a peculiarly ardent Hellenist, should have failed to notice it. It is perhaps possible to suggest a reason for an omission so remarkable. Herodotus himself had been brought up in one of the Dorian cities of Asia, at a time when it was in a state of vassalage to Persia. He had personal experience of the position of the Greeks under Persian rule. He must furthermore have been intimately acquainted with the life in the great Ionian cities which were subject to the Empire. From the Greek point of view, their political position was the reverse of ideal; but even a Greek could hardly have denied that their position might have been much worse than it actually was. The most objectionable feature,—the Greek tyrant governing in the Persian interest,—had been to a great extent removed before his time; and after the deposition of tyranny the cities seem to have enjoyed a large measure of local independence under Persian suzerainty. Whatever the extent or nature of the tie which bound them to the sovereign government, it certainly does not seem to have been such as to crush social and intellectual development on Hellenic lines; in fact, with regard to intellectual development, these very cities seem to have been first in the field, and to have been infinitely more prominent under Persian than under Athenian rule. Whatever the cause, whether fear or policy, or both, it is plain, on the evidence of the Greeks themselves, that the Persian Government was extraordinarily lenient and liberal in its treatment of subject Greeks. The Hellenism of the fifth century, social and intellectual, was, moreover, no tender plant requiring careful political nurture. It had struck its [4]roots deep into the very being of the race; and it may be doubted whether Persia could, even if she would, have eradicated so strong a growth.

It is therefore possible to exaggerate the consequences which might have resulted to Greek civilization had the issue of the great war been favourable to the Persian. The inherent probabilities of the case do not warrant the assertion that such a victory would have brought about the substitution of an Eastern for a Western civilization in South European lands. It is, moreover, extremely doubtful whether the Great King could have maintained his hold upon European Greece for any prolonged period after the initial conquest; and any attempt to crush the Hellenism of the land would certainly have led to insurrection in a country designed by nature to be the home of communal and individual freedom.

Speculation upon what “might have been” is ever open to the charge of idleness. It is, indeed, futile to attempt it in detail, by reason of the infinity of the factors which modify human action. But, inasmuch as what has been already said with regard to the possible results of the war might leave a wrong impression as to the legitimate deductions to be drawn from the main factors of a possible though imaginary situation, it is necessary to carry the speculation one step farther.

That a Persian victory, even if only temporary, would have immensely modified the political development of Greece in the last three quarters of the fifth century, goes without saying; and such a modification could not but have seriously affected the genius of Hellenism. The splendour of the life and literature of the last half of the century was largely due to the elaboration at Athens of a political and social system, the counterpart of which the world has never seen. Never before, and never since, has existed a community so large in which so great a proportion of its members has had time to think out their own salvation, and to work it out upon their own lines of thought. EASTERN AND WESTERN CIVILIZATION. Salvation may seem a strange word to use of a system which produced the pitiful record of the fourth century; and yet, from amid all the evil, failure, and folly of the [5]time there emerged a social order which was infinitely better than anything of the kind which had preceded it, and which was destined to form the foundation of the edifice of civilization in the western world at the present day. A Persian victory at Salamis, or even at Platæa, must have postponed the realization of those ideals which are the glory of the Greek people, and on which rests the claim of their race to the highest place in the history of the nations; and postponement might have made the full realization impossible.

The catastrophe of 480 had been long in maturing. The march of events in South-eastern Europe and Western Asia had been slow. Still, the two paths of development tended in opposite directions; and it was inevitable that those who followed them should meet in a collision, the shock of which would be proportionate to the forces of propulsion. The moral strength of those forces was enormous. The ancient civilization of the East, ages old, strong in development, the one ideal of the millions of Western Asia, came into contact through its most western off-shoot with a civilization which, whatever its origin, and whatever the influences to which it had been exposed, was in striking contrast to it. On the eastern shores of the Ægean the two first met.

It is impossible to say on the one hand what was the level of the civilization attained by the Greeks at the time they first settled on these coasts, more than 1000 years before Christ; and it is still less possible to say what was the state of the peoples they found there at the time of their settlement. Whether Lydia at this early age of its development had as yet come into contact with, and been influenced by, the civilization of the lands east and south of Taurus must also be matter of doubt. It is, on the whole, probable that it had; for the number and rapid development of the Greek trading towns on the East Ægean coast point to a considerable and valuable overland trade, whose roots would, in all probability, be in the lands of Mesopotamia, if not still farther east. The caravans from that rich plain would be sure to carry the infection of its civilization to the lands they traversed.

[6]But, in any case, neither the Greek nor this most westerly off-shoot of the Asiatic civilization can have passed beyond an early stage of development, nor, in so far as is known, did the representatives of either seek to inflict their own form of life upon the representatives of the other. Neither side seems to have been strong enough to conquer the other, even if either had been disposed to try. The Greek was content to trade; the various native races were without union, and cannot have been equal to the conquest of a people whose original settlements they had apparently been unable to prevent.

The great Phrygian kingdom which flourished in Asia Minor for several centuries had probably passed the zenith of its greatness when the Greeks first established themselves on the coast; and the Lydian monarchy, still in its infancy, had not developed into the greatness it attained in after-time. In the obscure and uncertain traditions of the Asian Greeks which Herodotus has preserved, this monarchy is represented as having had an existence extending far into the past, under various dynasties; but of its earliest history nothing is really known, and the little that can be conjectured rests on the uncertain foundation of mythical story. The Atyadæ or Herakleidæ of the earlier dynasties are mere shadow-kings in history. A recurrent theme in Phrygian and Lydian story alike is the fabulous wealth of certain of those rulers. They seem to have afforded the Greek his first glimpse of the splendour of the East.

Though, doubtless, the Greek trader traversed the Western Asian peninsula through and through in his trading journeys, the populations with whom he came in contact remained uninfluenced by a civilization they did not appreciate, and probably could not understand. The Lydians alone afforded an exception to this rule, because their position was exceptional. They were brought into close contact with the Greek, and seem to have implanted on a civilization of an Oriental type certain characteristics derived from Greek social life. RISE OF THE LYDIAN KINGDOM. It is doubtful whether such features of this civilization as are known to the modern world were characteristic of the Lydian race as [7]a whole in early days; it is more probable that the mass of the people remained in a comparatively low state of social development, and that the quasi-feudal ruling families of the land evolved for themselves a civilization copied from foreign lands, and were influenced especially by the reports which reached them of the life and glories of the great cities of the Euphrates plain.

The rise of Lydia to greatness seems to date from the early years of the eighth century before Christ. A feudal family established a precarious supremacy over the other feudal families of the land. Nevertheless, the kingdom seems to have acquired a stable unity which it hitherto had lacked; and the westernmost region of the West Asian peninsula gradually developed into a dominion more splendid, if not more powerful, than any which had hitherto existed among the strangely diverse populations of that part of the world.

Geographical convention has assigned this peninsula to Asia; and, under the influence of name-association, it has come to be regarded as being in every sense an integral portion of that great continent. In point of fact, however, it was at this time a borderland between Orient and Occident, approximating ethnographically rather to West than to East; though, in so far as it was influenced by the outside world, affected rather by the preponderant power and splendour of the East than by the comparative weakness and insignificance of the West. The true historical western frontier of Asia has varied at different periods of history between the Hellespont and the Taurus, according as this debateable land has been in possession of an eastern or a western power. But in the earlier days of the Lydian kingdom the region was politically centred within itself, or, rather, was an aggregation of political circles, and not, as in later times, a mere segment of a great circle, whose centre lay far beyond its borders. Those who know by experience the character of the barrier which, in the shape of Mount Taurus, separates this region from the adjacent East, are most emphatic in insisting upon the formidable nature of that wall of separation. It is not difficult to demonstrate that Taurus [8]has been in the past one of the most decisive physical features in the history of the world.

The great systems of civilization have had one of two origins. Either they have sprung up in those great plains of the world whose climate is favourable to ease of existence; or they have been developed by nations whose circumstances have been favourable to wide intercourse with, and experience of, the peoples around them. Egypt, the Euphrates plain, India, and China, are examples of the first; Greece and Great Britain are the most prominent examples of the latter class. As, however, the “civilizations of intercourse” must be largely dependent on navigation, which can itself be alone developed by long experience, it is plain that they must be of later development than the “civilizations of ease of existence.” Thus it is that, many centuries before any system of civilization of high development existed in Europe, the plains of the Euphrates basin had given birth to one which, had nature allowed it unimpeded expansion, must have spread to a great distance from its centre. The all but blank, impassable wall of Taurus prevented the West Asian peninsula from being thoroughly orientalized. Thus that civilization which was springing up beyond the Ægean was allowed to develop on its own lines, hardly affected by those pale rays of the glowing life of the East which the narrow passes of Taurus allowed to penetrate to the lands of the West. It was the Taurus, too, which protected the earlier stages of the growth of the Lydian kingdom.

East of the chain the Assyrian empire was living out a life of stormy magnificence. The records of its kings,—a wearisome tale of murder, conquest, tribute, and torture,—give, it may be, only one side of its history, and that not the best. Their exploits have as little perspective as their presentment of them. The immediate object is all that is sought; the past is dead; the present alone is living; the future is of no account. A land is conquered; its population is either decimated, wiped out, or removed elsewhere. Its wealth is plundered; and, if there is anything left on which tribute can be laid, tribute is laid upon it. Such is the record of one year. ASSYRIA. A few years later, even [9]in the case of lands previously reported as left desolate, the same process is repeated. There is no rest for the ruling race. For some inscrutable reason, its kings seem not to have had foresight enough to establish a strong system of administration for the conquered provinces. These are merely treated as sources of revenue, doomed to tribute,—a heavy burden indeed, but, at least in the case of regions not bordering immediately on Assyria proper, the only burden laid upon them.

Of the great empires which arose at different periods in this part of the world, Assyria seems to have been the least enlightened. Its real field of operation was bounded by the great mountain-systems on the north and east, by the Great Sea on the west and the desert on the south. Any operations undertaken outside these well-defined limits seem to have been of the nature of punitive expeditions directed against mountain tribes who had raided within these boundaries. Their lands were too poor to excite the cupidity of this brigand empire. If they remained quiet, Assyria left them alone, and devoted its energies to the exaction of tribute from the richer lands of the plain or of the Syrian coast. There are few records of expeditions west of the Taurus; and, though some lands are asserted to have paid tribute, there is no evidence whatever of anything like permanent conquest. The great mountain chain acted as a groyne which diverted the flood of invasion from the Euphrates region southward along the Syrian coast Thus it was that the growing kingdom of Lydia never came into hostile contact with the great empire. Yet the commercial intercourse between them must have been carried on upon a large scale; and, indeed, the prosperity of Lydia and of the Greek colonies on the Asian coast was due to their acting as middlemen in the commerce between East and West which passed along that route which formed in later Persian times the line of the royal road to Susa. It was an interruption of this intercourse, and a threatened diversion of this route, which brought about the opening of diplomatic relations between the two realms.

In the latter half of the eighth century before Christ, [10]the plains of Asia and East Europe were disturbed by one of those movements of thrust which are ever recurrent in their history; and a tide of migration was set up which was destined to have many more remarkable counterparts in later story. Under pressure of a race which may with a certain amount of probability be identified with the Massagetæ of after times, those mysterious peoples, the Cimmerians and Scythians, were driven from their homes in the northern plains and invaded in whole or in part the West Asian peninsula. Of the two, the Cimmerians settled in the region of the North bordering on the Euxine, and by continual raids made life a burden to the Phrygians and White Syrians of those parts. Some thirty unhappy years seem to have passed thus. The Phrygian kingdom was gradually broken up, and by 670 B.C. the Cimmerians found themselves on the north borders of Lydia, which had just taken a new lease of life under Gyges, one of the ablest and most energetic of its successive rulers. The possibility of invasion was only part of the danger which threatened Lydia. That Gyges could and did ward off in a fierce struggle with the northern hordes; but his resources were, unaided, not equal to the task of reopening the great trade route to the East which passed through the lands of which these hordes were in possession. He began negotiations with the mighty Empire of the East which, under the energetic rule of Assur-bani-pal, was at the height of its power. He sought to get aid in the heavy task which lay before him. There were difficulties about the interpretation of the message which his envoys carried to Nineveh; but these were overcome, and he received fair words in answer to his request. More than this he did not get. Assur-bani-pal had his hands full nearer home. He and his line seem to have been past-masters of the art of creating difficulties to be overcome; but the king seems to have had no desire to interfere in the affairs of a land whose geographical position was vaguely known to him as being near the “crossing of the sea.” He had enough self-created troubles at his very gates without going abroad to find them.

So Gyges got no help from Nineveh, and was obliged [11]to content himself with having successfully warded off the invasion of his own territories. For some years at any rate the great route eastward must have been difficult, if not actually impassable. This interruption of commercial relations by land with the East may well have led to that development of Lydian intercourse with Egypt of which the Assyrian records afford evidence.

The history of the Lydian kingdom, except in so far as it affects the fortunes of the Greeks in Asia and Europe, forms no part of the design of the present volume.

In the reign of Gyges, however, the relations between Lydian and Greek entered upon a new stage. The Lydian rulers had hitherto lived on friendly terms with most of the Hellenic towns on the adjacent coasts. Gyges went still further, and by assiduous cultivation of the Delphic oracle attracted the attention and regard of the Greeks of Europe, who thus for the first time became intimate with one of the great monarchies of the East.

For the new relations with Egypt, the Greek trader formed the connecting link. It was almost inevitable that an energetic ruler like Gyges should seek to get direct control of the main, if not the only, means of communication with an ally whose alliance flattered his vanity, and with a country whose wealth could not fail to benefit Lydian trade. It is evident, however, that he did not feel himself strong enough to attempt an overt attack on the Greek cities. That could only have resulted in a formidable resistance on the part of those centres of liberty and wealth. He devised a better plan, slow working but terribly effective, and destined in later days to lead to the undoing of the liberties of Greece.

Gyges has the distinction of being the first barbarian in history who saw his way to profit by the fierce political dissensions common to all Greek communities. By allying himself with factions in the various cities he acquired in many of them a preponderating influence, while he reduced others to subjection. Kolophon shared this latter fate; so did the smaller Magnesia near Sardes. With others he entered into close relations of friendship favourable to himself, since the continuance of the pressure from [12]the side of the Cimmerians made persistence in the policy of absorption impossible. The pressure increased instead of diminishing; and it was from this quarter that the final catastrophe came. A combination between the Cimmerians and other tribes of Asia Minor proved too strong for Gyges. He perished in a great battle. Lydia was overrun and devastated; and during the stormy days of the commencement of the reign of his successor, Ardys, the Asian Greeks found it necessary to join the Lydians in their death struggle. The Greek towns, though none save Magnesia appear to have been actually captured, suffered severe losses, which were but partially compensated for by successes won by Greek hoplites. Ardys, like his father, appealed to Assyria; and this time the Lydian appeal did not remain without effect, for the Cimmerians had turned east and were threatening the Assyrian border. Assailed by the Assyrians in the passes of Taurus, they were so terribly defeated that they ceased thereafter to be the formidable power they had been in West Asia during the previous half century. In the years which followed Lydia gradually acquired all that northern part of the peninsula which had been in Cimmerian hands.

Lydia was now a considerable power, extending to the Halys on the east; and as such it presented itself to the European Greek of the later years of the seventh century. To Lydia accordingly turned the thoughts of Aristomenes, the hero of the Messenian wars of independence against Sparta, when as a refugee he sought safety across the Ægean. Paus. iv. 24. 2, 3. Death overtook him before he had time to carry out his intention of appealing to Ardys for help.

Having attained a frontier on the east beyond which further attempts at expansion were dangerous, Ardys’ attention was naturally directed westward, where the thickly dotted line of Greek colonies practically cut Lydia off from communication with the Ægean littoral. They held the natural exits of that overland trade to which the prosperity of Ardys’ kingdom must have been largely due, and must have absorbed a large proportion of those trade profits which the Lydian might not unreasonably regard as his own. STRATEGIC POSITIONS OF ASIATIC GREEKS. Moreover, the relations of Lydia with [13]the great trading towns of Smyrna, Kolophon, Klazomenæ, Miletus, and Priene, were no longer of the friendly character of former days. The policy of Ardys consequently aimed specially at the reduction or absorption of these towns.

The inevitable was about to happen. The very nature of the peninsula made it all but certain that whenever a great State acquired command of the upper part of the great valleys of the Hermus, Mæander, and other streams, the towns which stood on their western exits must succumb to that State.

A glance at the map of Western Asia will show this.

The main physical characteristics of the country from the Halys to the Ægean are, (1) a great interior plateau; (2) a series of parallel mountain chains running from east to west, between which rivers, following the same direction, run down towards the Ægean, so that their valleys form a series of natural lines of communication between the plateau and the coast. There is no cross-chain running north and south, at the head of these valleys, to form a natural barrier towards the east. Access to them is unimpeded from that direction.

This physical conformation of the land was alike a curse and a blessing to the Greek trading towns of the coast. The valleys formed, on the one hand, natural routes for commerce of immense value to those who held their exits; but they also afforded natural highways for attack to any power coming from the interior which assailed the holders of those exits.

The disadvantage had not been so apparent while Lydia was still a comparatively weak State; but it was sure to come into prominence so soon as she attained to any degree of power. The weakness of the strategic position of those Greek cities is not less striking than the advantages of their positions from a commercial point of view. Their territories, besides being this void of any line of defence towards the east, were separated from one another by the ranges which divided the river valleys; and intercommunication by sea was rendered difficult by the long projecting promontories which separate the deep gulfs at [14]the head of which most of the cities were situated. From the point of view of joint action this was a very serious drawback. Nature had been doubly unkind to them in this respect. Not content with having made a base of combination on land impossible, she had made combination on sea difficult. Prosperity without liberty was the natural birthright of these Asian towns. Even when backed up by all the naval strength of the Athenian empire, their independence of the power on the mainland seems to have been in most cases partial, and in all precarious; and even independence gave them little more or better than a change of masters.

Priene was taken by Ardys somewhere about the year 620. Miletus was next attacked; but this greatest of the cities proved no easy prey. The war dragged on after Ardys’ death, through the short reign of his successor, Sadyattes; H. i. 17. and under Alyattes took the form of annual raids, designed to wear out the patience of the citizens. At last, mainly on the advice of the oracle at Delphi, a compromise was effected about B.C. 604, by which each side granted commercial concessions to the other, though matters remained politically in statu quo.

The comparative failure at Miletus did not discourage Alyattes in his enterprises against the towns. Kolophon, which had regained or reassumed its independence at the time of the Cimmerian trouble, was brought into subjection once more; H. i. 16. Smyrna, as a town, was destroyed, and its inhabitants forced to take up their abode in unwalled settlements. Klazomenæ well-nigh experienced the same fate. Alliances were made with other cities, such as Ephesus and Kyme. Alyattes would doubtless have prosecuted further his designs against the Greek cities, had not his attention been at this moment called away to the eastern frontier of his kingdom.

It was not from Assyria that the trouble threatened. That great empire had come to an end some years before, under circumstances of which the details do not directly affect the Greeks. A Scythian incursion, so prolonged that it seemed likely to terminate in permanent settlement, had broken it. MEDO-LYDIAN WAR. The final death-blow had been inflicted by [15]two peoples—the Medes, who inhabited the mountainous uplands beyond the Zagros chain which bounds the plain of the Tigris on the east and north-east, and the Babylonians, who had ever chafed under Assyrian rule.

Within a short period the Medes had pushed their frontier westward beyond the Taurus, and had reduced to subjection the country between that range and the Halys, a region which at times came within the sphere of Assyrian influence, but cannot be said to have formed part of that empire.

With all the vigour inspired by recent success, the Mede sought to push his way westward; and a fierce frontier war seems to have been waged for several years upon the Halys between Alyattes and Cyaxares, the Median king.

Pteria, a town whose position renders it the chief strategic point in the Halys region, commanding, as it does, the middle portion of the cleft-like valley through which the river flows, formed the point d’appui of the Lydian defence, and was the immediate object of the Median attack.

Of the war itself but little is known, except the important fact that it came to an end in a remarkable way. The opposing armies were drawn up for a battle, when an eclipse of the sun took place, which caused both sides to shrink from the engagement. It is calculated that such eclipses took place in Asia Minor in the years 610 and 585, of which the latter seems to be the more probable date of this unfought fight. H. i. 74. A peace was concluded through the mediation of a Babylonian whose name Herodotus gives as Labynetos; but in what capacity he acted as mediator is not known. The celebrated Nebuchadrezzar was ruling in Babylon at the time. Lydia apparently sacrificed Pteria and the region east of Halys, and that river became the definite frontier between the two States.

The story of this Median kingdom has come down to posterity in a form so imperfect that it is difficult to extract the small historical from the large mythical element contained in it. Its chief importance in history is that its [16]kings are the first of that series of Iranian dynasties which, whether Median, Persian, or Parthian, were paramount in the eastern world for many centuries. From this time forward the Iranian took the place of the Semite as the suzerain of the East; for the Babylonian realm of Nebuchadrezzar was but of comparatively brief splendour, and was soon absorbed by the less civilized but more virile power which became heir to its partner in the destruction of Assyria.

The Median king Cyaxares, who had warred with the Lydians on the Halys, lived but one year after the close of the campaign, and was succeeded by his son Astyages, whose chief claim to fame is that he was the last of the brief line of Median kings. Little is known of him. For the Greek the truth concerning him and his was lost in that mirage of legends which accumulated round the personality of the man who overthrew him, Cyrus the Great.

The myths, fables, and legends which the ever lively imagination of the East invented with regard to the founder of the Persian dynasty, have crowded the greater part of the real story of his life out of the pages of history. Their adoption by Greek historians was all but complete; though some, like Herodotus, sought to rationalize a few of the incidents reported. Did there exist no other records of his life than those which have survived in the Greek historians, it would be difficult to assert with confidence which of the reported details are true. Comparatively recent discoveries in the East have brought to light, however, certain annals of a Babylonian king, Nabonidus, a successor of Nebuchadrezzar, and a contemporary of Cyrus. From these records it is possible to reconstruct the story of some of the main events of what must have been a very stirring time in that part of the world.

Astyages the Mede had reigned a quarter of a century, when Cambyses, the prince of one of the vassal principalities of the Median empire, died, and was succeeded by his son Kurush, the Cyrus of the Greeks. This was about the year 559. The name of the principality appears in the records as Anshan. Its inhabitants were the Persians of history.

[17]

This people, which was destined to play so great a part in the two following centuries, were of the same race as the Medes. The only possible deduction to be drawn from subsequent events is that the connection between the two nations was very close. Its exact nature can only be guessed at. Any difference between the two must have been rather nominal than real; for the supremacy of the one race does not appear to imply the subjection of the other; and when, somewhere about 552, Cyrus revolted, and defeated Astyages, the Median army came over immediately to his side. It is hardly credible that such a thing should have taken place, had not the Medes regarded Cyrus and his family as being in some very real sense a part of themselves, and as possessed of some title to be their rulers. Both races were certainly Iranian. They were alike in religion and very near akin in language. It may even have been that the Persian was a tribesman of the nation to which the name Mede was given. Their nearest neighbours, the Babylonians, recorded the change of ruler, but not in language which could lead to the supposition that they regarded it as an event of great magnitude. They seem to have looked upon it as more or less of a domestic matter, an internal revolution.

The Persian empire was indeed the empire of the Mede under a new name; stronger and more vigorous than its forerunner, because the helm of government passed into abler hands. The Greeks themselves hardly recognized the distinction between the two, and used the names Mede and Persian in a general sense as synonymous terms. Nor has the perspective of centuries sensibly altered the nature of the picture as it presented itself to those who regarded it from a nearer point of view. The two nations, one in religion, one in civilization, one in social system, appear as one in the making of the history of the three centuries during which they played the foremost part in Western Asia.

During the thirty years of Astyages’ rule in Media, the Lydian kingdom enjoyed a continuous career of expansion. Whether owing to troubles at home, or to the severity of the check administered in the campaign on the [18]Halys before 585, Astyages made no attempt to extend the Median frontier towards the West. It is probable that he had his hands full with the work of consolidating the wide dominion which his race had so recently won, and the revolt of Cyrus may have been but the last of a series of insurrections on the part of his subordinate rulers. Be that as it may, Lydia was given a breathing space from attack, which, under the energetic rule of Alyattes, she used to the full.

The renewal of the assault on the liberties of the Greek towns of the Ægean coast followed immediately upon the close of the fighting with the Medes. Before five years had elapsed, the Troad and Mysia, with the Æolian Greek cities of the Hellespontine region, had been reduced. Even Bithynia seems to have been invaded about this time, and part of it secured by strongholds built at important strategical points. In the south-west Caria proved a harder conquest. Its population, from which the earliest professional soldiery in the Levant had been drawn, did not give up the struggle until about the year 566, well-nigh at the close of Alyattes’ reign. The Dorian cities on the coast seem to have shared its fate. On this occasion, at any rate, they were partners in its adversity.

It was in this campaign that Crœsus, that figure of pathetic magnificence, destined later to cast both light and shadow on the historical records of the Greek, first came into prominence. The mingled admiration and commiseration of after-time exaggerated his personality into the very type of human fortune and misfortune; and the picture of his life as drawn by Herodotus is probably no more than a truthful reproduction of the impression of him which prevailed a century after his death. Nevertheless the thread of fact runs unbroken through the maze of fiction, and it is possible to reconstruct his history with more reliability than can be claimed for the records of his predecessors.

As a youth he had incurred the displeasure of his father Alyattes by his extravagance, and had imperilled his chances of succession by the distrust which his conduct excited among an influential section of the population, [19]composed probably of staid merchants, who would be unlikely to sympathize with irresponsible and expensive frivolity. The danger brought him to his senses; and he apparently made up his mind that the Carian war afforded him an opportunity of winning a good opinion he had never tried to earn. How he succeeded is not known. He did succeed; for the fortunate issue of the war was largely attributed to his exertions and ability. He was just in time to save the situation for himself, since the years of his father’s life were numbered. About B.C. 561,2 Alyattes died, not before he had raised the Lydian kingdom to a greatness beyond what it hitherto had known.

It stood, indeed, on the same level as the great contemporary monarchies of the East, while as yet the Mede had not succeeded to the full heritage of that Assyria which he had helped to destroy. It absorbed for the time the attention of the Greek, when he gave his attention to anything beyond his home affairs. Its very splendour became a barrier of light which the Greek eye could not pierce so far as to see clearly what was going on in the region beyond, so that even the great Cyrus came not within the field of Hellenic vision until he had emerged from the comparative darkness of the lands beyond the Halys.

Archæological discovery within Lydia itself has done far more than the meagre records of contemporary history towards disclosing the characteristics of the civilization which was thus brought into strong contrast with that of the Hellenic lands and cities. It would be out of place in a work of this kind to enter into details with regard to it; yet the possibilities of the future were at the moment of Crœsus’ accession so significant, and of such world-wide importance, that it is impossible to pass over in silence the main features of a social system whose influence upon the [20]Hellenic world must have been very great, and might have been much greater.

The Lydians, a people of undeniable genius, seem to have built upon an indigenous foundation a composite civilization, made up largely of elements drawn from foreign lands. Assyria, Babylonia, and Egypt all contributed to its formation; and the influence of the Greek of the Asian coast and of Europe is unmistakable, especially in the last years of its independent existence. It was, indeed, in the main a “civilization of intercourse,” due to the important trading relations of the kingdom with the various nations which lay within its reach. Its main characteristics in the sixth century are Oriental, though the tendency towards its hellenization, fostered greatly by its rulers, is strikingly apparent. It must, indeed, on the other hand, have influenced the social life of the Greek cities within the borders of the kingdom; and it is difficult to say how far this influence might have affected the civilization of the West, had not the process of infiltration been brought to a sudden standstill.

It was, as might be expected from the variety of its origin, a strange compound of good and evil. From his very vocation the Lydian trader evolved a system of cosmopolitan humanity, rare in those ages, rare, indeed, in any age in eastern lands. Living at ease himself, he was naturally inclined to live and let live. The width of his trade connections, and the necessity of securing safe passage through foreign countries, would tend to make him cultivate friendly relations with the people around him. One thing that he evolved from the necessities of his mode of life has had as much influence upon the history of the world as any single invention of man before or since. The awkwardness of exchange and barter to a merchant whose trade had distant roots, and who had to make long overland journeys in the course of his business, led him to invent and gradually adopt one medium of exchange, which all peoples, however various their home products, would appreciate. LYDIAN INFLUENCE ON THE GREEKS. It required but little education in taste to make even the rudest of races set value on the most beautiful of all the metals; and the gold and silver [21]which Lydia produced so freely was stamped into the first currency of which there is record in history. Greek and Persian alike lost but little time in adopting so magnificent an invention.

The Lydian works of art which have survived show that the nation had attained to considerable skill in that respect.

But if the virtues of this civilization were great, its vices were equally so. The grossest form of immorality, that pest which the East seems to inherit like a moral leprosy, was prevalent. Certain tales in Herodotus show this to have been the case. The Greek did not escape the disease, and it may be that it was from the Lydian that he first caught it. Wholesale immorality of another kind was not merely prevalent, but received a religious sanction in the guise of that Aphrodite worship which in various forms sapped the vigour of the East. The town populations of Greece, especially those which, like the Corinthians, had closest intercourse with the Asian coast, caught this infection also.

It would have been contrary to the very nature of things had the Greeks,—a race peculiarly apt to learn both evil and good,—escaped altogether the influence of this Oriental social system at their doors. It is fortunate for posterity that its influence was short-lived. The very excellence of the general relations between the Lydia of Crœsus and the Greeks as a body made the Lydian influence the more dangerous. It was the bitter hostility which sprang up in after times between the Greeks and the representatives of that new Orientalism which was superimposed upon the Lydian form, which saved the Greek civilization from becoming itself orientalized. The danger which Greece ran in the great war of 480–479 was as nothing compared with the danger Hellenism would have run had the war never taken place. The bitter, lasting hostility which it roused was far less dangerous than friendly intercourse with a great empire, the heir of all the ages of a world-old civilization, which might have made a moral conquest of the Hellene, had it refrained from attempting a physical one. It was the war itself, rather than its issue, which proved the salvation of Greece.

[22]Crœsus’ succession to the great dominion which Alyattes had left was not undisputed. But the son had inherited the vigour of his father. He anticipated the plans of his rival. The pretender disappeared,—how or whither is not known; and his supporters, who were largely drawn from the feudal nobility of the land, met death in many grievous forms. Some of the Greek cities had more than sympathized with his antagonist, so to these he now turned his attention. All of them, Æolian, Ionian, and Dorian alike, were reduced to the position of Lydian dependencies, though in matters purely local they remained autonomous, if the name of autonomy can be given to a form of government in which a local tyrant played the part of administrator and political agent. Yet unpromising as was their position from the point of view of theoretical politics, they were in actual fact treated with marked consideration by Crœsus.

It is impossible at the present day to sound the motives which underlay the attitude which this extraordinary man adopted to the Greeks alike of Asia and of Europe. It may have been from pure self-interest; it may have been because Hellenism had cast over him the glamour which it cast over other barbarian monarchs. Whatever the cause, the fact remains that, when once he had reduced the Greek cities to that position of dependence which was necessary for the political homogeneity of his empire, he seems to have lost no opportunity of ingratiating himself in the eyes of his Greek subjects and of their kinsmen beyond the seas. At Branchidæ and at Ephesus he enriched the Greek temples with splendid offerings; and the wealth of the gifts he gave to Delphi excited the admiration of centuries. If contemporary report be not exaggerated, the value of his dedications to the great Hellenic shrine amounted to considerably more than a million pounds sterling of the money of the present day. Gifts of great value were also sent to the lesser Greek oracles.

The authorities at Delphi would have been exceptional among similar societies in all ages of the world, had they not shown appreciation of a devotee so wealthy and so [23]willing. He was made a citizen; to his embassies were given a precedence over all others.

It is difficult to imagine that Crœsus should have expended such enormous sums on the cultivation of friendly relations with the Greeks of Europe for purely sentimental reasons. The oracles were not the only recipients of his gifts. The friendship of prominent and powerful families in various States, such as the Alkmæonidæ of Athens, was bought with a price.

Perhaps the explanation maybe sought and found in the previous and later policy of the king. He had subjugated the Greek cities of the coast, and by so doing had advanced his kingdom to its extreme limits on the west. Unless he converted Lydia into a naval power, further expansion on this side was impossible. So he turned his eyes towards the East, where nature and the circumstances of the time offered what must have seemed a favourable opportunity for the extension of his empire.

It must, however, have been quite evident to him that any policy of expansion eastward could only be carried out with safety in case his rear was secured from attack, where danger lay, not merely in the recently subdued Greek cities, but also in the possibility of any movement on their part being supported by help from their kinsmen in Europe.

Considerations such as these must have had a large influence upon his policy.

The story of his operations in the East has survived in history in what is manifestly a very mutilated form. It is fortunate that Strabo has preserved some reliable details which Herodotus does not mention in his somewhat legendary account of the last days of the rule of Crœsus. The Lydian frontier had been extended to the Halys; but the motley collection of races and states included within the dominion was in some cases bound to the ruler of Sardes by comparatively loose ties. These ties Crœsus strengthened.

Affairs in Asia beyond the Halys were at the moment, when Crœsus brought his plans to maturity, about the year 548, in a condition which made all certain calculation as [24]to their issue impossible. The Median dynasty had come to an end some four years before, and with it the treaty concluded by Lydia with the Mede in 585 had come to an end also. Cyrus must have been an unknown factor to the Lydian, though doubtless the merchant travellers had brought back from the East many a tale of his energy and success. He was certainly a danger: and the question probably suggested itself to Crœsus whether he were not a danger which it would be wise to forestall, by pushing forward the Lydian frontier to that mass of mountains formed by the meeting of Taurus with the Armenian chains. Such a precautionary measure would be rendered the more attractive to the Lydian trader by the fact that it would lead to the inclusion within the empire of that rich mineral district on the south shore of the Euxine wherein the famed Chalybes dwelt.

Crœsus was wise enough not to enter upon this venture single-handed.

It is evident that the comparative indifference with which Nabonidus and the Babylonians had originally regarded the change of rulers in Median empire, had by this time given place to a feeling of uneasiness, if not of actual alarm. The easy-going, peace-loving antiquarian of Babylon might well be apprehensive as to what might be the next object of the uncomfortable enterprise of his energetic neighbour. Even then the faint outlines of the writing on the wall were well-nigh decipherable.

Amasis of Egypt had far less grounds for alarm; but even he seems to have caught the infection of fear.

With these two states Crœsus entered into negotiations, which resulted in the formation of a grand alliance, having for its object the suppression of the power which was so rapidly developing in the East.

The negotiations of Crœsus were not confined to the great powers. He sought and obtained allies in European Greece. The Lydian kings had had a long experience of the value of the Greek heavy-armed infantryman. Greek hoplites had fought many a time both with and against them. LYDIA AND SPARTA. The addition of a contingent of them to the grand army which the king was now gathering together would be [25]of inestimable value. There was evidently a difficulty about his obtaining such a force from the Greek cities of Asia; nor can there be any reasonable doubt as to where that difficulty lay. These cities had within the last few years been robbed of much of that measure of autonomy which they had up to that time enjoyed, and upon which they had set a value out of proportion, doubtless, to its real worth. The vivid discontent which such a loss must have aroused in Greek minds, a discontent the depth of which the experience of ages would enable the Lydian to gauge, would inevitably render them dangerous elements in a Lydian army. The cities did, indeed, with one exception, remain proof against Cyrus’ attempts to tamper with their loyalty; but their attitude at the time was probably as much due to caution as to fidelity. Their geographical position would not allow them to accept risks against Lydia.

It was, therefore, to Greece itself that Crœsus turned. The relations which he had so assiduously cultivated with Delphi enabled him to obtain its assistance in the negotiations. H. i. 69. The outcome was, so Herodotus says, that Sparta, partly persuaded by the oracle, partly flattered by the Lydian embassy, consented to give aid in the war. Moreover, the way to this alliance had been previously paved with Lydian gold.

It is true that this contingent never reached Lydia. Ere it had actually started, Sardes had fallen and Crœsus was either dead or a prisoner. Whether the delay in despatching it was intentional or not, the satisfactorily attested fact of such an alliance having been made is evidence that the Lydia of that day exercised a very real influence in Greece. Of the danger to which Hellenic civilization was exposed by Lydian friendship, enough has been already said.

That friendship was genuine and unaffected on the side, at any rate, of the Greeks. The relations of Crœsus with Delphi must have been largely instrumental in forming it; but what happened in relation to this very war showed clearly that the feeling of Greece towards Crœsus was built upon wider foundations. The Greeks had come to [26]regard him as a distinguished convert to that Hellenism they so much loved. The impression may have been false, but it was powerful. “He loveth our nation” is an article in a national creed whose possibilities can be hardly exaggerated. That the feeling had become independent of the relations with Delphi is conspicuously shown in the present instance by the fact that it was Delphi which administered to it a shock which the Greek world took long to forget. The remembrance of it was evidently vivid a hundred years later in the time of Herodotus.

It came about as follows. Anxious as to the issue of the great venture upon which he was entering, Crœsus sought to fortify or defeat his own resolution by inquiring of the oracles as to what the future had in store for him.

Two of the oracles consulted, of which Delphi was one, answered that “if he warred with the Persians he would overthrow a mighty empire.” The response was capable of two interpretations, of which Crœsus seized upon the most obvious; and was thus, so the Greeks thought, led to his undoing. Despite the pious faith with which Herodotus regards the utterances of the Delphic oracle, he is unable to conceal the tremendous shock which this apparent deception caused to Hellenic sentiment all the world over. To the Greek it appeared as though the oracle had betrayed its best friend and his also. Even in the cities of Asia, chafing though they were under recent subjugation, this feeling must have found some echo, whose resonance lasted till Herodotus’ own time. It is unlikely that he would ever have disclosed its existence had not the feeling been very widespread in the Hellenic world he loved. H. i. 90. The legendary story which he relates of the conversation between Crœsus and Cyrus, expresses evidently a feeling entertained by many besides Crœsus himself; and in the chapter which follows upon this tale, he shows that the Delphic oracle was forced by public opinion to attempt to explain away the apparent deception it had practised. FALL OF THE LYDIAN KINGDOM. The true explanation, which would have relieved it of a large part of the burden of the moral guilt, was one it dare not give in view of the prophetic character which it had to maintain before [27]the eyes of the world. Prophecy founded upon intimate knowledge of Greek affairs was very far from being the mere guesswork, wrapped in enigma, of its utterances relative to matters deep in Asia, of which it can have had no real ken.

The account of the campaign given by Herodotus is full of inconsistencies; but by comparison of his story with other incidental references to it in various sources, it is possible to arrive at an understanding of the main outlines of what took place.

The great coalition might have taken Cyrus by surprise, had not the plans of Crœsus been divulged to him by an Ephesian traitor, if a tale preserved by Diodorus is to be believed. The mere fact that he was able to anticipate the designs of Crœsus renders it probable that some disclosure of the kind did take place.

Forewarned and forearmed, Cyrus executed a rapid and adventurous march through the northern territories of the Babylonian kingdom, and must have been already near the Taurus before Crœsus received from his ally Nabonidus news of the coming attack. He was but half-prepared; but the danger was so imminent that he had to take the field with the force he had with him, while he sent urgent messages to his allies to come with all speed to help him. H. i. 75. He crossed the Halys into the district of Pteria, which he laid waste as a defensive measure. The historians, Herodotus and Polyænus, are hopelessly at variance as to what happened in the actual fighting that ensued. A great battle did take place: that is certain. It is also certain that after the battle Crœsus retired through Phrygia to Sardes; but whether he did so because he had been defeated, or because he had inflicted a severe check on Cyrus, and expected that a diversion on the part of the Babylonians would make it impossible for him to advance towards Sardes in the winter, is unknown. In any case, Nabonidus did not move, and Cyrus surprised Crœsus in Lydia. Crœsus, caught unprepared, made a desperate defence with such forces as he could collect; but he was shut up in Sardes. Of the real history of the siege the Greeks seem to have known little or nothing; [28]their chroniclers give the most contradictory accounts of it. But the town fell within a short time—taken, it would seem, by escalade. What became of Crœsus is not known. Bakchylides III. 23 ff. It is probable that he immolated himself upon a burning pyre. The tale was too shocking for Greek ears, and was softened down by a legendary addition to the effect that he was saved from the flames by divine intervention.

The sudden collapse of Lydia is one of the most remarkable incidents in history.

It fell in a moment, as it were, never to rise again; and it fell, not in the decadence of age, but at the very height of its young and vigorous life. To the Greek the spectacle was bewildering: nor is it strange that a catastrophe so sudden and complete, unparalleled, indeed, in the history of the world, should have so dazed the senses of those who were spectators of it, that they were never able to give a rational account of how it came to pass.

[29]

CHAPTER II.

PERSIAN AND GREEK IN ASIA. THE SCYTHIAN EXPEDITION.

Despite the great catastrophe which had just taken place before their eyes, the Greek cities had no mind to make an unconditional surrender to the power which had vanquished their old master. It was unfortunate that, after coming to such a decision, they did not combine in a common resistance. The inherent weakness of their strategical position, together with the incompleteness of the sympathy between Æolian, Ionian, and Dorian Greek, made such united action difficult. There is a terrible sameness in the drama of history as played upon this coast of the Ægean. The scenery admitted of but one plot, of which the leading motive was disunion. In the present, as in other instances, the Dorian states of the Carian coast went their own way. They threw in their lot with their Carian neighbours. The Æolians and Ionians were not altogether blameless in the matter. They did not at first show a bold front to the Persian, but offered to submit to him on the terms on which they had submitted to Crœsus.