.

COPYRIGHT

BY ALEXANDER KOGAN

PUBLISHING COMPANY, “RUSSIAN ART”,

BERLIN

MCMXXII

THE STORY

OF LEON BAKST’S

LIFE

TEXT

BY

ANDRÉ LEVINSON

B R E N T A N O ’ S, N E W Y O R K

THE AMERICAN EDITION OF THIS WORK

CONSISTS OF 250 NUMBERED COPIES

Nº. 247

PRINTED IN GERMANY

DR. SELLE & Co. A.G.,

BERLIN

PREFACE

![]() N the book of fame, the name of Leon Bakst is writ large. Many a time and oft, illustrious critics have heralded his praises. In speaking today of the contribution made by Bakst, there is really nothing that one can add or improve upon. The inventory of his achievements has been completed; the unexampled influence which he never ceased to exercise has been rightly evaluated. Nevertheless, there remains a task which must not be neglected. Paris, to be sure, enthusiastically watched the development of his art;{14} but for us, Russians, has been reserved the most thrilling experience of all—that of chronicling the unfolding of his genius. We have here the spectacle of a towering, unusual, self=revealing personality, and of a style that develops progressively and that blazes new ways after bitter struggles.

N the book of fame, the name of Leon Bakst is writ large. Many a time and oft, illustrious critics have heralded his praises. In speaking today of the contribution made by Bakst, there is really nothing that one can add or improve upon. The inventory of his achievements has been completed; the unexampled influence which he never ceased to exercise has been rightly evaluated. Nevertheless, there remains a task which must not be neglected. Paris, to be sure, enthusiastically watched the development of his art;{14} but for us, Russians, has been reserved the most thrilling experience of all—that of chronicling the unfolding of his genius. We have here the spectacle of a towering, unusual, self=revealing personality, and of a style that develops progressively and that blazes new ways after bitter struggles.

More than that, in order to obtain a composite picture of his work, in order to arrive at a general estimate of the man, we must try to reproduce the intimate atmosphere of his artistic development, the material and intellectual surroundings which shaped his course.

As a compatriot and contemporary of the master, I have, on the whole, breathed this same atmosphere. I have been an eye=witness of those earlier creations of his that mark an epoch in the history of Russian painting and of the Russian theater. This knowledge constitutes my qualification for attempting this biography. The latter would be incomplete unless his childhood and adolescence were also to be recalled. In so far as this period of his life is concerned, I am reporting Bakst’s own words; with moderation I have supplied a running comment.

Thus these pages present the first attempt at a story of Bakst’s life.

THE YELLOW DRAWING ROOM

It was in a dull and mediocre home of the well=to=do middle class that our artist who, as the originator of expensive pageants and the dispenser of unheard=of splendor, was destined some day to modify profoundly the whole conception of the western stage, spent his early childhood. Leon Bakst’s family lived at Petrograd, on Sadovaia street. Now, there is nothing more incongruous than the different sections of the Russian capital—“the most phantastic in the world,” to use a phrase of Dostoievski.

The Sadovaia is a rather narrow but very lively street, which cuts across the market=place and is flanked by the arches of three huge galleries where countless small tradesmen carry on their business. Here, in the adjacent streets, in the gutters of the sidewalks which, depending upon the time of the year, were muddy or dusty, Roskolnikov lived his life{16} of superhuman anguish; a few steps from here, in a gloomy red house, during all of a terrible night Rogojin and Prince Mishkin watched over their murdered love; here, too, one day Nicholas I, the giant=like autocrat with the countenance of an Apollo, standing at the entrance to the temple which overhangs Sennaia Square, by a single imperious word brought the revolting mob, which was exasperated by the plague and the shedding of blood, to their knees.

Thus to a dreamer who is haunted by memories the very stones of this district, which has been the silent witness of tragic fates, whether imaginary or real, seemed to be harbingers of bad luck.

And yet, notwithstanding, there is nothing more noisily commonplace than the daily routine in broad daylight of this same Sadovaia: large public houses, but devoid of rustic cheerfulness; mechanics’ shops in which the songs had died. Dull boredom of an industrious popular life, but how discolored, deadened, and enervated by the peculiar atmosphere of this artificial town—this city of officials, of soldiers and of ghosts!

Nevertheless the little soul of the well=behaved child, blocked up though it was by realities that afforded no way out, possessed its wondrous sesame, its secret garden. Every Saturday Levoushka would walk toward the Nevsky Prospect where, but a few steps from General Army Headquarters with its imposing semi=circular façade of red, from Winter Palace Square, and from the Admiralty—a veritable fairy=land of lofty architecture—, his grandfather lived, a noble and vaguely mysterious being who, without in the least being conscious of it, awakened in the future artist a reverence for Beauty, a holy fear of the Unknown.

The child thus came into unusual surroundings which constituted the artificial paradise of his early life. Whatever it was—precocious influence or atavism—this fascination dominated the life of Bakst and at least decided his calling. At any rate the master himself, who one day told me at length about his earliest recollections, seems to think so.

His grandfather, a peculiar fellow, was a Parisian of the Second Empire, a man of society who, it may well be, not long ago had been{17} out walking with the Mornys and the Paivas. An amiable Epicurean he was, a man of fine discernment in the manner of his time, who had set up a retreat for himself at Petrograd that was well adapted to his ineffaceable memories.

Everything in this home of dreams appealed to the sensibilities of the child—the brocaded silks, the graceful and heavily gilded trinkets. But his greatest delight was the large gilded parlor, with panels of yellow tapestry, with furniture of rock and shell=work in the style of 1860, with its white marble, its yellow flower stand, filled at all times with rare plants, and (this constituted his supreme happiness) its four gilded cages in which canary birds were chirping. In a corner, on a stand, a large model of the Temple of Salomon displayed its imaginative architecture. A large painting had for its subject the lament of the Jews before the demolished walls of Zion, for the former Parisian “lion” did not renounce his race; he had not forgotten Jeremiah over Theresa.

The irritable old man at times scared the impulsive and vivacious urchin; kindhearted old grouch that he was, he often angrily charged the wretched disorder up to the young lad. Levoushka was therefore not sorry to see his grandfather leave for his customary Saturday promenade, for this was indeed the right moment for him to make the large clock, with its mechanical doll, ring, and to wind up the music boxes of every description that were to be found in the yellow drawing room.

His own home furnished Leon no such emotions. Besides, the indifference to matters of art was practically general in the Russian intellectual classes of that time. The grandfather was therefore the idol of the child, his sole arbiter of good taste. No sooner had he returned home, than Levoushka would turn his room upside down and would try to arrange his modest furniture according to the exquisite æsthetic principles of the yellow drawing room; and he would try to hide from view the things that were devoid of beauty.

Yet throughout all this there was never any idea of painting. Later, his grandfather never got to know that Bakst was sketching. Meanwhile Leon was about to become ten years old. His entry into school put an end to his weekly pilgrimages to the Nevsky Prospect. Sesame had closed.{18}

THE UNGRATEFUL AGE

No sooner had Leon become encased in the uniform which distinguishes the city student from the provincial youngster in gray—viz., a black blouse with silver buttons—, than he came to know the monotonous and depressing life of the Russian schoolboy: rising by lamp=light during the long winter months; returning with his school=bag on his back; suffering the petty annoyances of an oppressive discipline and the black boredom of official education.

It was then that he discovered the theater. Not that he had ever been there. Like everybody else, his family had subscribed to a season ticket at the Italian Opera which was then at the height of favor and which eclipsed all efforts of an unappreciated national music to win its way; but our hero, being too small, was not allowed to go to the family box. With great difficulty, however, he had gained the privilege of staying up on Mondays—the days on which his family had the box—until their return. With delight he would then listen to his brother’s account of the “Puritans” or the “Favorita” and their tragical and pompous vicissitudes.

Tired of listening without acting, he constructed his own theater. He cut out his heroes from the sheets of colored paper soldiers, his princesses from the engravings in popular fairy tales illustrated at Epinal, his court ladies from the fashion magazines. Then he would place his actors on a paste board stage and “brush in” the scenery in water color with paint plundered from his color=box. The subjects were plentifully provided by the librettos of Verdi’s operas, augmented by supplementary murders. As for the audience—it was never lacking, Leon having always been the appointed and recognized entertainer of his little sisters.

This play of make=believe did not, however, entirely satisfy his precocious ardor. The strong desire for disguising and masking is, after all, quite general among children, who possess a genius for dramatizing the facts of life. Improvised plays were, therefore, put on. The most frequently recurring motif was the visit of the doctor. There was much{19}

illness at Leon’s home! Young Leon, besides being stage manager, would now play the role of the doctor with black robe, now that of the druggist, now even, with self=denial, the rather contemptible part of the patient.

One day, as he had concocted a drug by diluting green coloring matter, he pursued realism to the point of swallowing the concoction. He fell ill. Only with the greatest effort in the world was it possible to save him by making him drink a quantity of milk.

Throughout all this, however, we do not yet see the painter come to the fore. Indeed, our schoolboy was decidedly not a success at drawing,{24}

and with envy he watched how his chums sketched fine battle scenes upon the margins of their note books. His life’s calling announced itself for the first time when he was almost twelve years old. His school, known as “the sixth gymnasium”, was making preparations to celebrate the{25}

centenary of Joukovsky, the celebrated Russian poet. A good portrait was wanted for the ceremony. Accordingly, a prize competition was organized. Bakst decided to enter it. He reverently took home the little engraving which was to serve as model, and four or five days later he{26} brought back his drawing. The prize was awarded him, and his masterpiece put in a glass frame and hung in the gymnastic hall. From then on Bakst was unanimously proclaimed a painter, and he was able to pride himself on winning many a prize.

Leon’s father was not much pleased over this sort of success, especially since bad marks were raining thick in the other studies. He conceived the notion that his son’s predilection for drawing was due to sheer laziness. He therefore positively forbade him this pastime which, he argued, interfered with serious studies. Leon therefore continued drawing in secret, at night=time, by the light of a candle.

On the other hand his accomplishments brought him the friendship of his drawing and penmanship teacher, who became much attached to the youngster. Andrei Andreevitch was a diminutive little man with bowlegs; but this tail=coated freak in blue was fired with a divine enthusiasm. Striding about the class room he would talk incessantly to the pupils, now pondering the volutes of an acanthus leaf, now discussing the lives of great painters, their struggles, their triumphs. So volubly and so well did he speak that he stirred deeply the imaginative soul of little Bakst and awakened all the latent passion in him. Subsequently, the artist’s entire magnificent life was to be animated, as it were, by these rhythmic fits of intellectual fever, from which he was to emerge renewed, transformed, his mind’s eye turned toward unexplored horizons.

The profession of painting, therefore, suddenly appeared to Levoushka to be the highest of all destinies—one bearing the halo of heroism. Filled with this romantic dream, he was anxious to quit school at once. And he insisted with such impetuosity that his parents, routed in the argument, decided by way of setting him right to seek the advice of the sculptor Marc Antokolsky, a friend of the family and a recognized authority on all matters pertaining to art. The late Antokolsky was little known in Paris where he used to live, nor do people care much about him in Russia today, although his works, which are quite numerous, fill the museums of Moscow and especially of Petrograd. So deceptive is artistic glory!

For indeed, he had his day of glory. In Russia he was the sculptor of the century—of that nineteenth century which had lost the plastic{27}

arts almost completely. The conception of a strict naturalism placed at the service of humanitarian and social ideals, dominated by the idol People, a conception that also characterized the notable and prophetic “Association des expositions ambulantes”, was also his. Moreover, Stassov, the voluble and prolix critic who composed for the great Moussorgsky the monstrously confused text of “Khovanshchina”, turned Antokolsky’s mind toward Russian history.

And thus, through his bronze and marble sculptures, Antokolsky became the historical illustrator and portraitist of Russia. He wrought Ivan the Terrible, Nestor the Annalist, Peter the Great, and even Ermak the Cossack, conqueror of Siberia. With keen psychological sense he also composed the likenesses of heroes and martyrs of free thought: a dying Socrates, a Spinoza and a Christ insulted, the latter work being conceived in the spirit of Strauss and Renan. All these monumental figures which greatly stirred his contemporaries no longer show any signs of life.

There remains the personality of Antokolsky, which was in every respect a pure one. Not without reason did this poor and pertinacious young Jew, who hardly knew how to write Russian, become the idol and the oracle of two generations. We see but too clearly today that he travelled the wrong road. But he had faith. His artistic convictions were unalterable, unselfish, absolute,—those of a fanatic. More than that—a thing seldom to be found—, this fanatic was kindness itself.

Antokolsky, then, on being consulted made much of the misfortunes and bitter disappointments that one embarking upon an artistic career must expect. But he was not unwilling to look Leon’s drawings over. Pestered by the youngster, his father sent several sketches to Paris. Lo and behold! when the reply, so anxiously awaited by the boy, arrived, it was favorable, decisive, almost intoxicating. The master had found the drawings quite well done and advised the boy’s going to the Academy of Fine Arts, on condition, however, that he pursue his general education.

Thus Leon, the intractable and mediocre schoolboy of the day before, was to become a painter, a chosen and quasi-legendary being. He was then sixteen years of age.{32}

THE TWO SPHINXES

Leon, then, presented himself for examination but failed. Before being admitted to another test he had for a year to practice drawing from models; and only after he had solved the mysteries of this form of academic discipline, was he admitted. For another year he kept abreast of both his artistic studies and his general secondary education; soon, however, he neglected school and, after a few feeble attempts, gave it up altogether. Let us state the fact without bitterness: Bakst never received the Bachelor’s degree.

The first day that Bakst, attired in his new green uniform, wended his way along the granite embankment toward the Academy and, having passed under the eyes of the two Sphinxes from Thebes with a hundred gates which guard the sanctuary, decided to enter, his astonishment and his proud ecstasy knew no bounds. However, despite the grand pretense of a temple, the Imperial Academy of 1890 was a rather curious institution.

The academic instruction which flourished at the beginning of the century, maintained its power and authority until the close of Nicholas I’s reign. But from 1863 on it was badly shaken by the famous secession of the “Thirteen”, with Kramskoi at the head. These thirteen later became the first “wanderers”; they were destined to herald the arrival of a certain humanitarian realism closely related to the teachings of Proudhon and of Courbet. They professed the haughtiest contempt for disinterested pictorial beauty, for mere virtuosity, yes, even for sound craftmanship based upon traditional experience.

Among the “pompiers” classicism had degenerated into hackneyed copying; teaching became vulgar pedantry. Among the revolutionaries classicism was the complete and absolute negation of art, admitted only as a function of social apostleship. But the younger artists had public opinion behind them, which hailed the catastrophe as a liberation. Yet for thirty years the Academy, powerful solely because of its official authority, continued to stick to the past and to live outside the pale of a throbbing artistic life.{33}

Not until 1893 did the “wanderers”, led by Makovsky and Repine, enter the citadel in order to establish a bold and frank dilettantism while still respecting the remnants of the old Academy. At that time Bakst had already broken with his first masters; we shall soon see why.

Let us first, however, briefly complete the history of the institution on the Nicholas Embankment. Toward 1910 a reaction set in against the anarchy of the “wanderers” and in favor of a classic revival, of a rehabilitation of craftmanship. This movement was of short duration, however, for the October Revolution abolished the Academy and established free studios upon its ruins, the management of which was placed in the hands of artists who supported the Communist regime. On the day of its death the Russian Imperial Academy was more than 150 years old.

Thus, at the Fine Arts School, Bakst found a training that clung to unchanged formulæ, but that was decadent, inert, and lifeless. He spent three months drawing from bas=reliefs and one year sketching models. Then, after having passed the class in costumes and copied draped mannequins, he was admitted to the studio class. His teacher, Tchistiakoff, did not encourage him to continue; he considered Bakst a promising sculptor, and whenever his pupil tried to talk painting to him, he would invariably turn the conversation to sculpture. Tchistiakoff’s colleague, Venig, was more far=sighted and, while disapproving of a certain vivacity and truculence of colors which netted young Bakst the ironical title of “Rubens newly ground”, he was not unfriendly to him. This meant a great deal, for it was impossible to think of any more intimate relations—any communion of ideas or of feelings—between the pope=like officials and their pupils who were as yet unknown quantities.

Far more important were his relations with his fellow students, especially with the class that was about to leave. At school and at his paternal home he had been placed in a position of isolation because of his artistic aspirations; here he found himself surrounded by young people devoted to that same art that was viewed with such suspicion by the Russian intellectuals of yesteryear. At the Academy Bakst met Nesteroff who, following Vasnetzoff and contemporaneous with Vroubel, was to attempt a revival of the ikon,—a revival which, besides proving{34} abortive, was more in the nature of sentimental and artificial imitation. This craze for old national art went hand in hand among certain students with a strong animosity against the “métèques”; besides, anti-Semitism was officially encouraged and stimulated, since it served to side=track the hatred which was more and more undermining the autocratic power. Bakst, sensitive and meticulous, was grieved at this. He therefore clung all the more closely to Seroff, several years his senior, who was finishing his education and who aspired to winning the Grand Prize for Painting—the gold medal. This future portraitist was a son of the celebrated musician whose masterpiece, “Judith”, is known to Parisians only by partial selections. Already he had achieved, in the eyes of his fellow students, the intellectual and moral prestige that was due to the uprightness—albeit somewhat morose—of his character and the tenacity of his effort. Soon, indeed, he came to the forefront of his generation.

This man, already matured, reserved, and little given to effusive outbursts, took a fancy to the red haired young lad. The pair would sit together in the studio; they would spend the evenings chatting in the modest students’ apartment where Seroff lived and drinking plenty of tea. Those were the happy days! They lasted for eighteen months. Clouds were, however, gathering over the head of Bakst who had already given repeated offense to his superiors by his whims of independence. A free competition was announced in which “The Madonna Weeping Over Christ” was to be the subject and the Grand Medal of silver the prize. Bakst joined the competitors.

He sought inspiration from those artists of his time who had attempted a revival of religious subjects by displaying a realistic setting—thus breaking away from the iconographic traditions of the Renaissance—, by giving care to ethnographic detail, by minutely studying the expression observed. These artists included Repine and Polienoff in Russia, and Munkaczy abroad. But, carried away by a youthful enthusiasm, he wished to go beyond the fastidious and cautious realism of these painters and make a ten=strike.

He therefore chose a canvas of enormous dimensions—almost seven feet in length—and plunged into his work. For the characters of the legend he set down Jewish types that were obviously overdone, and imparted{35}

a movement to them that imitated the gesticulation of Lithuanian clothing merchants or of elders in the synagogue. As to the Virgin, she was an old, dishevelled woman, with eyes red from weeping. Our candidate was, to be sure, vaguely conscious of the fact that he was digging his own grave; nevertheless he obstinately persisted in his daring attempt.

What anguish he suffered while he awaited the decision of the jury on the winding staircase that constituted the Bridge of Sighs for the young daubers of Petrograd!

And justly so, for when his name was called and he appeared before the tribunal, he saw his canvas crossed out by two furious strokes of crayon, and he had to listen to an official rebuke by the president.

The next day he quit the Academy under the impassive glances of the two bearded sphinxes of pink marble, emerging from the gloomy twilight.{40}

A WRONG START

Leon was free now and left alone with his pride in his recent revolt; but there was also a great void in his soul. A country holiday out at Pavlovsk, the delightful suburban residence district where Constantine, the grand duke-poet, lived, afforded him salutary diversion. In the beautiful English park—the loveliest in all Russia—, where every clump of trees, every hill, every lawn forms part of a grandly-devised and complex general plan conceived by an architectural genius; in this park, in which he walked about carrying the burden of his liberty—a melancholy figure, he found what he lacked most: a friend. This new-found friend was a cartoonist by the name of Shpak, a pupil of Repine, and, though but a mediocre artist, yet one who gave himself to painting with a passionate and unselfish spirit. He guided Bakst in looking for motifs, spurred him on to direct observation of Nature, and awakened in him the proper respect for his profession. But this influence soon gave way to another.{41}

Luck would have it that Bakst, during that same autumn, chanced to meet Albert Nikolaievitch Benois, the celebrated water-colorist who had no rival in Russia. He was a member of that “dynasty” of Benoises who have played so prominent a part in the artistic development of Russia. Albert Benois, a handsome, chivalrous and affable man, handled the brush with remarkable ease. He possessed a technique that was as natural for him as bel canto singing is to the Neapolitan beggar. But while his productions, at the same time that they possessed certain qualities of good taste and true knowledge of his art, nevertheless were rather too tame, their success in the eyes of the public was complete. This success of the “master”, who was fêted and flattered by his aristocratic and feminine entourage, and who was unanimously elected to the presidency of the society of water-color painters, dazzled young Bakst, blunted for a while in him the haughty pride of the seeker after new truths, and stimulated other ambitions in him. The fierce rebel who sneered at the Academy suddenly craved Success!

He achieved a success that was immediate, brilliant, and disastrous. Soon he began to neglect landscape painting in favor of the society{42} portrait. Having tasted the apple, he next painted Eve. And, as he abandoned himself to these effeminate and futile pursuits with that same insatiable fervor with which he went into everything, he undertook, he simply allowed himself to drift. Besides, his good friend Shpak was no longer there to awaken his sleeping artistic conscience—he had died quite suddenly. Serov, too, was far away in Moscow and unable to warn him.

When I questioned him about this period of his life of which there are few traces left, Bakst spoke about them quite eloquently, yes, even persistently. He took evident pleasure in this confession; he seemed even to relish the mortification that it must have cost. Was it that in this race toward the abyss he tasted something of that spirit of adventure, of that happy faculty of spending without counting, of giving oneself body and soul to God or the Devil, which, indeed, was a part of his nature? Or was he dreaming of those pretty hands of women, slender but strong, which stroked his curly hair? As far as we are concerned, we must content ourselves with recounting briefly the outstanding facts in the early history of our friend and hero.

The most important of these is a long stay abroad. At Paris he made friends with Albert Edelfeldt, a Finnish painter and a remarkable man, to whose lot it fell to break the ground for the birth of a national art in his own country, in that he transmitted to it the enlightened knowledge of France. It should be noted in passing that all the Norse revivals which endowed the Scandinavian countries with an intense and original artistic life had their origin on the banks of the Seine. Edelfeldt was neither a creative genius nor an artist in the vanguard. He stuck to the cautious methods of a Bastien=Lepage. But he was a forceful and able painter. Some of his canvases are to be found in Paris, among them, if I remember correctly, his portrait of Pasteur.

The habit of working outdoors, the study of daylight and its effect upon massive subjects which Bakst pursued with his new friend who also in some respects became his teacher, contributed powerfully toward his success in performing the enormous task that was soon thrust upon his youthful energy. The Russian government asked the Prodigal Son{43}

of the Imperial Academy to paint a canvas that was to have for its subject the arrival of Admiral Avellan in Paris.

Perhaps the reader remembers that this visit which, unless I am very much mistaken, took place in 1893, was one of the first formal ceremonies arranged in connection with the nascent Russo=French alliance. This canvas, the result of painstaking and honest labor, which displays a freshness of color and a virtuosity of touch that is by no means vulgar, is preserved today in the Navy Museum at Petrograd. Was the young rebel of yesterday to become the Roll or the Mentzel of the imperial fastes? Today we know that nothing of the sort happened.

One afternoon as Bakst, back from Paris, was lording it over a tea table surrounded by beautiful ladies, and was basking in the sunshine of his reputation, with flattering chatter all about him, he noticed a young man enter whose manners at first offended him. With a monocle in his eye, with haughty pride writ across his dark=complected face, round=shouldered, attired in the student’s green blouse with blue collar, he carried on the conversation with an ease that bordered upon disdain and insult. Yet in the very arrogance of the young upstart there was something that fascinated. Bakst took him aside and, when he pressed him for an expression of opinion as to what he thought of his painting, the young man replied candidly that, while he had the profoundest respect for the technical mastery of his questioner, the painting itself absolutely displeased him, and for good cause.

This young man’s name was Alexander Benois. As for Bakst, little did he imagine that he had arrived that afternoon at a turning point in his artistic career.

THE CLUB

For a number of years a group of students from May College a private institution, had been in the habit of meeting at the home of their comrade, Alexander Benois. Among them was Constantine Somoff, a son of the venerable director of the Hermitage, and the future originator of “Echoes of Days Past”; Philosophov who later, when he was associated with Dimitri Merejkovsky, was destined to become one of the revivers of religious sentiment in Russia; and others besides who afterward constituted the nucleus of the society named “The Artistic World” and who still later supplied the staff of the Russian Ballet. Unique, indeed, was the atmosphere of this house.

I have already had occasion to speak of the Benois family. They were the descendants of one of those numerous immigrants who for more than a century, from the accession of Peter the Great till the Moscow Fire, were called upon to help in the transformation of Russia. All of these newcomers went through a similar experience: the tremendous opportunities for initiative, the vast geographical extent and the artistic impulses of the young empire called forth the highest development of their abilities. Many a mediocre artist—or at least one assumed to be mediocre—who had become half suffocated amid the rabble of the western world, became transfigured in these favorable surroundings. The originality of the Russian character, the breadth of view of the grands=seigneurs of Catherine II’s time, the primitive simplicity of the life of the people—all this stirred their imagination. And so these men, who transplanted into Russia the artistic methods of the West, the conceptions of style and the traditions of art that had matured in Europe, became Russians themselves in heart and spirit. More than that: it is to these “Russianized” fellow=countrymen of ours that, in a large measure, we owe the birth of a modern Russian art.

The Benoises were related to the Cavos family, a veritable progeny of artists. Alexander’s maternal grandfather had been a noted composer of music, his uncle a theatrical architect of distinction. The Cavos family were of Venetian origin and never lost contact with their former{49}

fatherland; the Benoises had French blood in their veins. All this is of importance to those who are interested in looking for the origin of certain aspirations, of certain artistic inclinations and habits of mind, in atavism or in the call of blood. All of which did not prevent the Benois brothers, two of whom we already know and the third one of whom was an architect and later was made rector of the Academy of Fine Arts, from becoming the eminent Russian artists that in fact they are.

As for Alexander, from earliest childhood he possessed all the qualities needed for becoming, if not an intellectual leader, at least an intellectual centre. His general culture, broad indeed and so varied as to have become eclectic; a certain pedagogic inclination,—a tendency to instruct, to educate, to make ideas spring forth; added to this, a liveliness of temperament, an acuteness of perception which made him a{50} malcontent, a wide=awake dreamer—all these rare qualities determined his life’s work. His attempts at painting, excepting only his theatrical creations, never seemed able to free themselves of a certain amateurishness. But this was a natural complement to the fact that he was primarily a theoretician or rather a man of artistic tastes who re=enforces his intuitions and his sensibilities with an exact sense of logic and with the true talent of a writer.

For many years Alexander Benois has been the most famous critic of Russia. He is passionate and imaginative. He proceeds either by invective or by panegyric. He is a thunderbolt. He gets worked up over some artist, some idea. Oftimes he is mistaken and his candidate for fame fails. That is due to the fact that Benois, who had really constructed his hero from his imagination, endowed him with his own ideas, and magnified his own conceptions in him, would suddenly, some nice day, leave the poor wretch to his own designs.

When Bakst was admitted to this group, or club, the school boys had become students and the original circle had widened. Philosophov had introduced into it a cousin of his, just in from the provinces,—a fat, chubby lad, exceedingly free in his manners, dictatorial and quite aggressive, inexhaustible in paradoxes which at times were absurd, but which he defended to the limit without in the least attempting to be polite about it. Benois was the soul of this group; the newcomer was to become its will, its moving power—he was to lead it to its supremest heights. The name of this fellow from the provinces was Serge Diaghileff.

Now what was it that transpired during these interminable confabs? The club had set itself up as a supreme court which was to judge the quick and the dead. Before doing anything constructive—they didn’t know themselves what—its members first wanted to wipe out everything existing. They would agree upon the victime, appoint someone as prosecutor, and then conduct a trial. The defendant might be a Shishkin or a Verestchagin—in any case he was one of those celebrities whose wrongly acquired reputation was debasing the real character of Russian genius in the eyes of the whole world! But this whole work of tearing down could not satisfy this enthusiastic group of young people. They felt the need of giving themselves over to something, of consuming themselves{51}

for something. At first their idol was Tchaikovsky, the composer of the “Sleeping Beauty”. Tchaikovsky had already become famous; there was therefore no “Battle of Hernani” to fight. It was merely a question with them of which work of this master should be given preference. They decided upon the “Queen of Spades” and placed it upon the pinnacle. What thrilled our friends about this work was the fact that it conjured up the 18th century in Russia. The action of the opera, the text for which was taken from a story by Pouchkine, takes place amid a setting that is an exact reproduction of “Old Petrograd”,—amidst a scenery that is familiar and famous. The promenade in the summer garden, the little bridge over the winter canal—this, when displayed on the stage, called to mind anew the beauty of the venerable capital—a beauty ever present, but unappreciated and neglected—and rehabilitated its declining fame.

If I have dwelt rather at length upon the feats and exploits of a group of unknown youths, it is due to the fact that these young men, who after theater would walk along the quais during the “white night” singing a duet from the “Queen of Spades”, or would lean pensively over the cold granite parapet to listen to the clock of the Cathedral of Peter and Paul pealing forth its crystal melody over the gloomy walls of the prison fortress,—it is due, I say, to the fact that these young men were destined to reshape Russian artistic sense from top to bottom. Later, on the eve of the new century, the “Mir Iskousstva” Society was founded; with the generous aid of Princess Tenicheff, a magazine was published; art expositions were arranged. A new epoch was beginning. Bakst helped to shape it—and we already know that he gave himself to every task whole heartedly.

At this point I do not propose to narrate the story of “Mir Iskousstva”. It was a revolution and was outrageously attacked as such. But its exponents held that it saved Russian art. Today some people contend that it was a menace to art. A quarter of a century lies between these two conflicting opinions. It is not for me to judge which is right. But Bakst’s participation in the work of this society forms a beautiful page in the life of my friend and therefore, too, of this story of mine. And my task would be incomplete were I to omit giving a brief description of this great movement of ideas which for a long time determined the future of Russian art.{56}

“MIR ISKOUSSTVA”

The small vanguard took position hastily; impetuously it fell upon the enemy. Diaghileff, charging at the head of this handful of friends, sounded the rallying cry. He was successful. Moscow, too, had its raising of the shield. Serov supported the movement. Levitan, the landscape painter, contributed his tremendous popularity to the young cause. During this recruiting fever mistakes were not wanting; for instance, Vasnetzoff, the insipidly sweet imitator of icons, was singled out for praise. He had soon to be dropped. But instead Golovine, Polienov and others joined them who drew upon the real popular sources. It is{57} further true that they almost succeeded in “reforming” Vroubel, the great romantic decorator who was haunted by the Demon.

Above everything this group was looking for allies from abroad. These were to be found at the very gates of Petrograd. A “young Finland” was rising about Edelfeldt as founder—the Axel Galiens, the Jaernefeldts, the Enkels; in short, all those who were destined to endow the “country of a thousand lakes” with a national art. The Finns accordingly took part in the first exposition in which “Mir Iskousstva” faced Russian public opinion. At the second there appeared French guests who after three generations found their way back to Russia.

This proved a decisive feat. An end was thus put to the isolation in which a waning Russian art found itself. For, at that time the whole European artistic movement was ignored in Russia. The prize winners of the Academy would go to Rome to perfect themselves and would there copy the Stanze of Raphael, or else, perhaps, they would go to study historical painting under Piloty, the De la Roche of Munich. The moving spirits of the school—a Kramskoi, or a Repine—would return from their western travels with nothing but contempt for the “futile” (as they called them) masterpieces of beautiful painting or else an infatuation for the virtuosity of the brush of a Fortuny or a Meissonnier.

Diaghileff and Benois flung the doors wide open. A motley crowd enters pell=mell; even the “decadents” of the Viennese Secession, with Renoir and Carrière. Mistakes are made; there is as yet no scale of values; the obscure Belgian, Léon Frederick, is put upon a pedestal while Cézanne is ignored until 1904. The reason for this is the fact that this group at first has no positive program. But its negative influence is inestimable. Repine, one of the most powerful exponents of this ideologic naturalism which I have mentioned in passing, launched a counter=attack in the name of the survivers of traditional academic style. Diaghileff, by his virulent reply, threw the champion of routine out of the saddle. It is a great period of ringing battles, of hard contests with the adversary who mangled even Ingres’ very name. These struggles were the more heroic since the public remained averse to them.

The editorial offices of their magazine were the hot=house in which new ideas were hatched and the staff headquarters where the big{58} offensives were planned. Now, the editorial staff itself was divided into two sections. In the large salon we find Philosophov, handsome and slender as a thoroughbred courser, who meets the contributors to the literary section. There is Merejkovsky, who contributes his best works to the review and who introduces us to the art and the doctrines of Tolstoy and Dostoievsky; Leon Shestov, the apostle of “eradication” with his emaciated face of a Jewish Socrates; Rosanov who pried into the very depths of the sexual problem, a towering spirit who used to bare his inmost thoughts with candor. Of all these men, who were radiant in their young fame, Rosanov alone did not profess a supreme philosophical contempt for the fine arts. The painters, accordingly, would shrink back from the haughtiness and the affected attitude of the literary folk and would seek refuge in the office of the secretary=general, the headquarters of the artistic section.

There they would find Bakst, who was collecting the material that oftentimes was queer enough, and who in fact worked out the whole review. No task was too hard for him. He would group the various component parts and make up the pages. It would happen that Diaghileff, disconcerted over an engraving that came out badly and that had the earmarks of a confused work, would come to Bakst who would take up the work on the plate and give form to an amorphous jumble of touches. Another one of his steady tasks was that of decorating the book, of designing the cover, of drawing the ornamented letters, of supplying the tail=pieces. In this connection it should be recalled that the art of book decorating was revived at the end of the last century. The English, with Walter Crane at the head, started the procession. It was an Englishman, furthermore,—Aubrey Beardsley—who designed arabesques of extraordinary sharpness and delicacy upon the geometrical quadrangles of the pages. This new method was also being experimented upon in Petrograd. A number of artists of the second generation of “Mir Iskousstva”, such as Narbout and Mitrochin, are exclusively “vignettistes”. As for this first group, they had to do everything and accordingly they did everything. Benois, Somov, that other Russianized Frenchman Lanceray—all were experts at this art. Bakst, too, went through it. There are magazine covers of his extant{59}

on which statuettes in Directoire style flank a medaillon, or on which there are artistic frames. At the same time he tried his hands at pure illustrating; there is, for instance, a water-color of his which illustrated “The Nose”, a grotesque story by Gogol. Today we look upon these designs as the first attempts at the masterful costume-pages of later days. “Bakst has hands of gold”, wrote Benois in his history of Russian painting, a work of which we shall speak again later. He admired his manual skill and the elasticity of his spirit and of his workmanship. But he was unconscious of his powerful personality.

Later on, dissatisfied with pen sketching that was then reproduced by the mechanical process of engraving, the group tried themselves at original lithography. Here, again, Bakst was successful: a head of{64} Levitan brings out in sharp juxtaposition the intense black and white of the drawing.

Thus, then, we see Bakst working away at his table, which is covered with waste paper, with photographs and proofs. Around him, people talk idly, or loll about the couches, or draw caricatures, or debate. Then, through a cloud of smoke produced by ten cigarettes, Diaghileff comes rushing in, chasing a new rainbow. He tells of his latest discovery, or he scoffs at some idol that he adored the day before. His enthusiasm is as intermittent as it is uncompromising. He is the life of this party of outspoken, unreserved painters; he cares little for men of letters. Alexander Benois, on the other hand, forms the connecting link between the two clans; he arranges and coordinates everything by virtue of his broad and supple understanding. Soon new initiates—Grabar and Jaremitch, the artist=writers, and Kouzmin, the poet=musician, and others—join in the work of strengthening the somewhat difficult union of these two sections.

Within this community of painters, however, there was little agreement as to the road that should be followed. They agreed in their hatreds, but differed as to aims. Diaghileff, always hyper=sensitive to the sensations of the day and ready to take his ideas out of the clear sky, would misjudge the value of ephemeral tendencies and therefore

at times get himself into an impasse. Thus he allowed himself to be carried away into enthusing over that atrocious “modern style”, the architectural vestiges of which today disgrace every large city in the world. Bakst together with his older friend Serov set himself against painting in the style of Gustav Klimt and against architecture à la Olbrich in the name of an honest, direct and robust art.

The weak spot about all this combativeness and intellectual ardor, which proved fatal and unavoidable amid these divergent points of view, was the lack of creative ability on the part of the group. This group had deposed and duly trampled under foot the art of the “wanderers” with its social tendencies and its worship of the moujik. It had done this to the greater glory of an art that is unselfish and creative. But almost immediately its members turned toward literature. Among all those former members of the Club (I except only Serov and{66} the Moscovites), there was not a single painter in the real sense of the word. Benois, who never when working at a canvas could completely overcome his amateurish clumsiness, Lanceray, later Doboujinsky—they all were first and foremost illustrators, rather than painters, who were steeped in precious recollections, who gleaned from every style and who discovered forgotten beauties.

With this select group, then, the motif prevailed more and more over its execution; the brush became a means of interpreting a history perceived with a sort of sentimental homesickness mixed with irony. Is it surprising, then, that the retrospective attitude got the upper hand more and more, and that the offshoots of this movement were sacrificed to a propaganda for the past?

As a matter of fact, discovery followed upon discovery. Preceding generations, going into Russian extremes, became infatuated with the idea of progress. Accordingly they either ignored or misunderstood their national past. Then, under Nicholas I the czar-gendarme, the old architecture was disfigured by German builders. As for the unique and grandiose beauty of the structures in the style of the Empire and of Louis XVI,—buildings without parallel in the occidental world—these were confounded by the public with that implacable hatred that it bore toward the regime that had erected and that was maintaining them. An educated Russian could not possibly find anything beautiful about the Winter Palace, this fine masterpiece of Rastrelli; he would decline to admire the Admiralty Building because the defeat of Tsushima was prepared within its formidable walls. The writer of this sketch was himself brought up in this atmosphere of hateful contempt for the “official ugliness” and the “style of the barrack.”

Benois and his friends discovered this slandered beauty and became enamoured of it. Later on we shall see how Bakst discharged his debt of gratitude to old Petrograd, this wonderful city which rose miraculously from the surface of the waves.

But the surprises were not yet over. In his history of modern Russian painting, Benois with boldness and with charming eloquence recalled the founders of this style of painting, the portrait-painters of the eighteenth century, especially Levitzky and Borovikovsky. He cast{67}

overboard all existing estimates and showed up the emptiness of the “wanderers” school. But his justified and impetuous enthusiasm proved—or nearly so—the undoing of “Mir Iskousstva”.

The magazine deteriorated before one’s eyes. Side by side with it Benois brought out a collection, or analytical inventory, called “The Art Treasures of Russia”. The creator became a collector. Ceaselessly he and his friends collected. Bric-a-brac occupied a prominent place. Icons of the school of Novgorod were dug up, likewise family portraits done by serfs in the old households of the nobility, mahogany furniture dating back to the Peace of Tilsit, and popular likenesses.

For a time Diaghileff allowed himself to drift. As usual he treated this craze for the past on a grand scale. He even resumed it in a definite effort of which I shall speak later. But for the present he and his friends felt themselves reduced to the role of custodians of a museum{76} or of benevolent guides, a thing that was repugnant to his ambition and his temperament. He looked for a way out. The stage alone seemed to offer it.

Naturalism had just won its greatest triumphs, thanks to the Moscow Art Theater. But if comedy was taken possession of by the naturalists, the opera and the ballet could react. Already Mamontov, the famous mæcenas who discovered Shaliapin, had ordered stage decorations from the Moscow painters, Vroubel and Golovin. At Petrograd everything was given a trial. I cannot, without exceeding the limits set me, speak at greater length of what became of this movement; some day, perhaps, I shall be able to strike its balance. As a matter of fact, I have already had to enlarge considerably upon my subject in order to set the subject of my sketch down in his proper surroundings, in that unique atmosphere, created by historical and personal contingencies, which is ignored for the most part by the Russian people, and which entirely escapes the attention of the foreign reader. Besides, this union of a handful of men who were determined to restore the artistic greatness of their country was so brotherly, so fraternal that it would be wrong to differentiate between their respective roles and artificially to isolate their efforts.

THE THREE KNOCKS

Resolutely Diaghileff turned his co=workers towards the theater. The time was propitious. Vsevolojsky, the director of the Imperial theaters, had just resigned his position which he had filled so brilliantly. Himself a dilettante nobleman and a man of good taste he had personally designed most of the costumes that, under his direction, were built for the ballet and the operas. He had to a large extent reconstructed the Russian and foreign repertoire, devoting himself to Tchaikovsky and making a place for Wagner. A galaxy of stars surrounded him. Marius Petitpas, the greatest living choreographer, exercised his successful dictatorship over the ballet. A brilliant young woman, just out of school, was about to eclipse the celebrated Italian virtuosos. Highly respected{78} painters—the Shishkovs and the Botcharovs—who were experts at the art of stage decoration, executed the ideas of their director. In short, he did everything. Was it his fault that his activity fell within the worst epoch of a century that was called the stupid century? Is he to be blamed that the sources of his inspiration and the quality of the documents consulted by him bore the marks of that terrible decadence of the artistic instinct of which the year 1900 marks the climax and presages its end? However that may be, he prepared a glorious end for an obsolete art. The old opera passed away in beauty.

Yet with all the extraordinary perfection of execution, a certain uneasiness was germinating. Vague manifestations of independence were threatening the rigorous traditional discipline. In the midst of this crisis the helm was given to a young man. Prince Serge Volkonsky, who had distinguished himself in the Court theater by his splendid bearing and his clever acting, belonged to one of the noblest Russian families. His grandfather had taken part in the famous “Decembrist insurrection” of 1825; his grandmother had followed her husband to his Siberian convict prison with a devotion that inspired Nekrasov to write a celebrated poem. Volkonsky let the dead bury their dead and from the very first made his appeal to the young men and women—to Diaghileff and his friends. They plunged into their work: a revival of Delibes’ “Sylvia” was decided upon.

The Mir Iskousstva painters agreed to make their first attack upon the stage together. Accordingly, they divided up the work by acts, Alexander Benois leading—Benois who even today, after his successful collaboration with Stravinsky, retains a real feeling of reverence for Delibes whom he places, without hesitation, in a class with Wagner. Bakst and Serov also collaborated.

But the opera was never put on. There is a veritable hoode about this “Sylvia”, which kept haunting the Russian artists and yet was never produced. The late Andrianov, an exceedingly good dancer, was about to show an abridgement or sketch of this piece, but the attempt came to naught; Fokine dreamed about it vainly for many years.

As to this first attempt at cooperative work, it failed for personal reasons. From the beginning Volkonsky felt his prestige as manager{79}

threatened by the consuming energy and the unscrupulous ambition of his “employé”, Diaghileff. To be sure, Diaghileff, conscious of his actual superiority, carried himself as though he were the boss. Fearing he would be supplanted by this maire du palais, the director requested Diaghileff to resign voluntarily. Diaghileff would do nothing of the sort. Exasperated, Volkonsky promptly discharged him, by applying the famous “paragraph three” of the rules and regulations to his case, by the terms of which the “government secretary Diaghileff” was forever barred from all public appearance. Who knows but that to this act of administrative jealousy we owe the grandiose effort{88} of the “Russian Season”? Excluded from official life, Diaghileff, the great condottiere of art, could unfold his full power!

Diaghileff left, his friends followed, a great gap closed in about the director, and several months later, not being able to have the last say in a quarrel with a star who was both famous and powerful, Volkonsky had himself to resign and leave.

Bakst, however, had not participated in this boycott of the prince; he plunged into his work for its own sake. But it was not at the Marie Theater that he made his real debut. Grand-Duke Vladimir Alexandrovitch had brought back with him from one of his frequent trips to Paris the text for a pantomime, the author of which was Fèvre, the comedian. This play, The Heart of the Marchioness”, found favor with the directors. It was decided to play it at the Hermitage Theater, an auditorium reserved exclusively for the Imperial family and the members of the Court. It was connected with the Winter Palace by a passage. The French actors of the Michel Theater, under the direction of the maître de ballet, Enrico Cecchetti, executed the pantomime before an audience of grand dukes and chamberlains.

Vladimir entrusted the scenery to Bakst. The latter conceived a semicircular pavilion as stage setting. For costumes he went straight to authentic sources and utilized the elements for devising a good ensemble. He brought a new idea to the theater: that of style. That is, at least, what eye-witnesses claim; nothing has been preserved of this work of his.

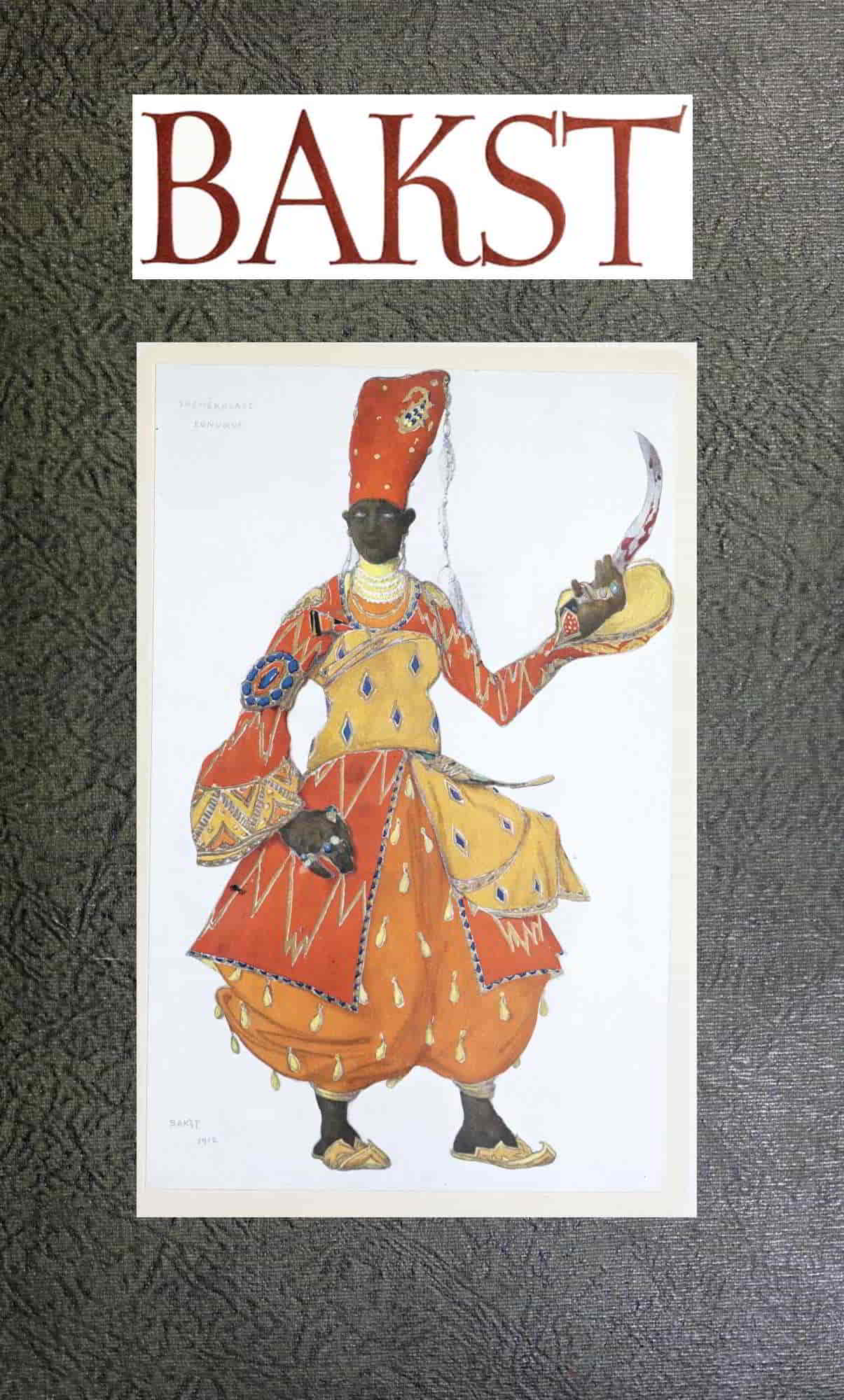

As the pantomime was tremendously successful, the Emperor had this show put on at a gala benefit performance in the Marie Theater—and this is how Bakst for the first time appeared on the most famous of all Russian stages. This winter of 1900, then, when for the first time he went upon the stage that, according to Goethe, “means the universe”, decided his future. Who could today imagine what the fate of modern scenerie would be without the contribution of Bakst? And who could conceive of a Bakst remaining a stranger to the theater? It took him ten years to find his place. The three knocks struck home. For the first time the curtain rises over a work of Bakst. Ten years later Paris will crown “Sheherazade{89}”.

THE THEBAN GATE

Meanwhile Colonel Teliakovsky had succeeded Volkonsky. He owed his appointment as director to the fact that he had been in the Horseguards with Baron (later Count) Freedericksz, minister of the Court. A ludicrous figure he was—this horseman promoted

to be stage manager—, without either ideas or prestige and consequently unable to contribute anything of value. But he gave others a free hand—and that is a great deal during a period of fermentation and revival.

Thus, soon after his appointment, he authorized an experiment of far-reaching importance. Alexander Theater was preparing to bring out Euripides’ tragedy, “Hippolytus,” the attempt being made to produce it as nearly like the ancient original as possible. The young stage{90} director, Osarovsky, hoped to make a grand coup. The play was translated by Merejkovsky in exceedingly beautiful verse and with an extremely intense modern feeling. Among the Russian intellectuals of that time, Nietzschean ideas were held in great fascination. Now, in this early masterpiece the philosopher had transfigured the whole conception of the spirit of the ancients. Under the marble-like and placid guise of the Greece of Apollo’s time he had revealed the Dionysiac ecstacy, the pathetic distress and the mystic impulse of the masses. What had been considered as the key to their souls, viz., this sovereign and plastic art, was but a sham emancipation.

For a quarter of a century the government had tried to curb turbulent youth by means of the classical ferule. Greek was loathed as much as was the royal blue of the gendarme uniform. But the translation by Merejkovsky and the enthusiastic eloquence of Professor Zielinski, scholar and poet, who commented upon it as “the birth of tragedy”, caused great surprise and soon extreme fondness for it. It was necessary, however, in order to bring about this rehabilitation of antiquity, to make use of the best possible medium, namely, its consecration by the stage.

The scenery and costumes for “Hippolytus” were ordered from Bakst. After an interval of four years there followed “Oedipus at Colonnæ” and Sophocles’ “Antigone”.

It was an arduous task indeed, for the problem was that of adapting the essential dualism of the Greek tragedy—its lyric choruses and its active players, its dithyrambs and its dialogue, Dionysius and Apollo—to the arrangement of the modern theater, with its odd-shaped stage, like a box opened toward the side of the spectators. Bakst made the attempt. Once having entered upon the road to Thebes he solved the enigma of the Sphinx without stumbling and forced open the gate. By raising the background of the stage he made the foreground available for the proscenium, with the altar of the god of the tragedy in the middle. On this proscenium the choruses executed evolutions, the choristers chanted the strophes and anti-strophes rhythmically, while the ensemble of supernumeraries scanned certain final verses. At the end the leader of the chorus would ascend the steps which connected the proscenium with the platform in order{91}

{94}y

to pronounce Fate’s supreme sentence upon the protagonist who had been prostrated by the gods.

Thus, for the first time, an attempt was made at a logical dissociation of the rhythmic and dramatic elements of the ancient theater. Years were

to elapse before the German Max Reinhardt invented the monumental staircase and the proscenium of Lysistrata; and still a longer period until that same intrepid pioneer let loose upon the arena of a circus the hysterical multitude of a chorus of wild persons. Bakst was the first, not only in Russia, but in the world, to try to work out a stage and a{100} conventional plastic language that was in accord with our modern conception of ancient art.

The Greeks who faced each other in the tragic dilemmas of “Hippolytus” and especially of “Oedipus” were no longer those classical personages

with rounded gestures, draped in white, blue or red tunics that looked like a schoolboy’s drawing after a plaster=cast relief of Phideas. They displayed the angular shoulders of the warriors on one of Aegina’s bas=reliefs; the conical helmet with a visor protecting the brow and the nose, as well as the metal shin protectors, tended to simplify the lines{101} of the actor. On the other hand the garments were brightcolored; the purple robe of Creon was resplendent with its ornamentation copied from Ionian pottery. The sixth century dispossessed the fifth, archaic art crowded out the classical canons, the intense colors of many hues

obtained preference over the marble whiteness of the statues. People breathed again; they felt themselves freed.

The great age of Pericles, which for three centuries had been exploited by every academy of Europe, which had been vulgarised, debased, enervated by the Alma=Tademas and the Siemiradskis,{102} seemed gloomy, formal, deathly cold. Besides, an art that is perfect and definite, and that has reached its zenith affords no occasion for further research, for further development. It condemns its followers either to imitating it or else to diminishing it. Instinctively Bakst took issue with the academic rules. The fact that he possessed this divination of the right road to take is what placed him several years ahead of his contemporaries.

For he was quite alone in his passion for this Greek antiquity which at every new turn seemed different from every preconceived notion. His friends of the “Mir Iskousstva” were entirely taken up by their craze for rococo curios or for the majesty of imperial architecture; Diaghileff was looking for Russian portraits of the eighteenth century and was preparing the famous exposition of the Tauride Palace; Alexander Benois was living at Versailles, fascinated by the sight of regal splendor. The only one who followed his efforts with solicitude was Serov. So that, when Bakst felt the urgent need of testing his intuitions by direct observations, of knowing positively what he had merely guessed at, he succeeded in persuading the great portraitist to join him on his voyage of exploration into archaic Greece—a journey that was one of the outstanding events of his intellectual life.

Our great master has reserved to himself the task of some day telling in detail the thrilling events of this journey. With that devotion to friendship that is characteristic of him he has kept a minute account of the utterances and impressions of Serov’s manly and delicate mind. It will make a splendid volume some day.

Serov had guided Bakst’s first steps. This Greek expedition was Bakst’s return gift. With the help of these antique realities, which served him as striking arguments, he turned the tormented realist, the sensitive psychologist that Serov was, to a study of syntheticized painting expressing itself in broad and severe forms. And so Serov, pupil of Repine the “wanderer”, portraitist of important Moscow merchants and of great Russian intellectuals, brought back from this voyage a memorable “Abduction of Europa”. His days, however, were counted. And once again Bakst had to continue his solitary way unaided.{103}

TERROR ANTIQUUS

Bakst did not go to Greece in order to say his “prayer upon the Acropolis”, to venerate the Attic serenity, “the sublime grace and the sweet grandeur” discovered by Winkelmann and Goethe. He visited hot Argos, and Mycenæ with its tomb of the Atrides which several years before had inspired the poet d’Annunzio with the panting dialogue of his “Dead City”; Mycenæ whose gates called forth in him something like a homesickness for Egypt. He strolled about Crete, among the remnants of the palace of Minos, dreaming about Medea the Sorceress, about the Minotaur conquered by Theseus, about the monsters, the Titans, all those brutal or mystic figures—the Gorgons, the Eurynies—who by their incessant assaults shook the pedestal where the Divine Archer defied them. The fantastic and passionate conception of the stage decorations for the Greek tragedies and ballets which were to earn such applause in Paris had its origin in these meditations of his in the occult presence of Hellas’ clear sky.{108}

But there was something else that made his heart beat fast as he strolled among the cliffs of Crete. That was the wind which blew up from the shore—a wind that was perfumed and that seemed to come from the vast Orient hidden in the fog. Who knows but that in such moments the call of the ancient Asiatic was indistinctly awakened in this Occidental Jew? Certain it is that underneath the chisel and the polishing tool of Greek culture he discovered the lavish, ardent and sensual oriental raw material. And the archaic sculptures, massive, with rigid frontlets, straightway transported him to Egypt. Then, too, his readings—Maspéro and the book by Fustel de Coulanges about the “Antique City” which had captivated him—confirmed his theories. He therefore did not hesitate to take from the Egyptians the ornaments in live colors with which he embellished the costumes for his “Oedipus”.

One cannot help but wonder, when one lets “Cleopatra”, “Helen of Sparta” and “St. Sebastian” pass in review, what would have happened if this extraordinary man had not been born on the banks of the Neva and in the fullness of the nineteenth century! Would he, under the pharaohs, have added new figures to the dancers on the tombs of Sakkarah? Or earlier still, would he, as a Phœnician sailor, in his leisure moments have designed the figures on the prows of the triremes of Hamilcar? He would well have fitted into the brilliant, arid, implacable atmosphere which forms the setting for Flaubert’s “Salambô”. But enough of these digressions.

What he had observed and meditated upon during these feverish weeks he intended to mass together in one single work, a decorative synthesis and at the same time a philosophical symbol: Terror antiquus, ancient terror!

In the foreground of the picture, cut off by the frame at knee-length, a colossal archaic Cypris rises. The hair of the idol is draped about its head in fluted curls; the large eyes with their distended pupils have a magic fixedness; a ferocious grin plays about the corners of the lips. The goddess carries a blue dove in the palm of her hand. Powerfully modeled, she turns her back to the picture, to the fury of the elements, to the panic distress of men. Impassive, implacable she turns away from this world which is tumbling. Behind the statue the eye{109}

beholds a landscape, an archipelago seen from a high elevation, and displayed like a map in relief; cliffs submerged by the rising waves; diminutive humanity seeking refuge under the porticos of the temples and attempting to escape the inevitable; an enormous stroke of lighting rending the air. It is the twilight of the gods, the last judgment of the Greek world, the end of Atlantis.

With its mysterious mixture of congealed grandeur and mad anguish the panel, when it was exhibited (if I am not mistaken) with the Association of Russian Artists, created something of a sensation. People flocked to the lectures of Viatcheslav Ivanov, the poet=philosopher and author of a treaty on Dionysios and the religion of the gods, who explained this Greek Apocalypse.

As for Bakst, this work of his constituted a striking but isolated episode in his life as an artist. Man of the theater that he was, his aim was that of utilizing and transforming space in accordance with his vision; here he transformed a surface, in the sense of material and philosophic depth.{110}

THE SPIRAL ROAD

Into this period of researches and visions in Greece falls many an episode that is entirely different but no less significant. Since 1903 Bakst had been using the ballet of the “Dolls’ Fairy” on the imperial stage. It furnished the prototype of those romantic productions, of those entertainments for children which are colorless reflections of Hoffmann’s Coppelius or of Andersen’s tales and in which one sees toys awakened to an artificial and mechanical life by a magic wand—entertainments, furthermore, which have become vapid by their being produced on innumerable German stages. Also, he rendered homage thereby to that “old Petrograd” that was dear to the members of “Mir Iskousstva”.

The prologue, which represents the busy coming and going in a doll shop in the capital city of 1830, is acted by a big crowd of people—shop=attendants, customers of every sort, small merchants and grand ladies, lackeys and grenadiers, mailmen and policemen produced on the stage as the naive action unfolds. All these masques and costumes are absolutely authentic, but they seem fragile and delicate like a dream. The fact is that the documents from which the dossier of the decorator was constructed were anything but commonplace. Bakst did not seek his information from the more direct sources supplied by the engravings of that time: he went to the show cases of porcelain ware.

Too little are the charming products of Russian porcelain makers—the Gardners and the Popovs—known. To be sure, they often merely misrepresent, in their style, the models from Saxony or Sèvres, but they do it with a naive flash of pure color that appeals to rustic artisans. But side by side with such imitations these obscure Russian artists modeled an entire little world of their own in tender clay—cossacks in uniform, drunken serfs, nude women, coiffed “en cabriolet” and burying their chilly hands in fur muffs. Whatever tastefully conventional there was in these figures, Bakst transposed into the language of the theater. Ever since that time this form of ballad (or “boutade”, as it was called{111}

in the time of Cardinal Mazarin), the dancing for which had been designed by Serge Legat, a splendidly endowed young man who committed suicide in a fit of passion and despair over a love affair, has maintained its place on the program. Examples of it are the “Carnival”, “Phantom of the Rose” and “Secret of Suzanne”, that delightful little=work in which one already sees Napoleon evolving from Bonaparte.

But Bakst had by no means given up his painter’s easel for his theatrical sketches. Numerous portraits of his bear out this fact, such as that of the philosopher and lay theologian Vassili Rosanov, of his friend Benois, of Levitan the remote emulator of Corot who discovered the intimate and poignant beauty of the humble Russian landscape, of Diaghileff and his old nurse. Painted with keen observation, with facility of touch and in vivid colors that spread over broad surfaces, these portraits coming from the school of Serov showed nothing of{120} that painful affectation, of that anguish of definitive, absolute expression with which the Moscow master often endowed his canvases to the point of tiresomeness. In the case of Bakst there is nothing of the exact analyst who dissects and torments the soul of his model. With our artist everything seems to be improvisation, happy inspiration; it is a style for which the fine term “prime=sautier” (ready=wit), once coined by Montaigne, is exactly appropriate.

His growing familiarity, however, with Greek art, which is in a high degree plastic and linear, turned him in the direction of more concentrated and more simplified processes. The painting of vases in the merest outlines and on flat surfaces neatly silhouetted, imperceptibly drew him into the path followed by Ingres. He therefore gave up his paint brushes in favor of the lead pencil and the colored crayon. In his portraits thus designed it is the line which circumscribes the person, which sets it out in space, which expresses its character and suggests its size. Thus the Russian painter is already en route towards that strictly linear transposition of a body of three dimensions without the aid of the model, or of any standard of values, or of any material record; a style which some day Pablo Picasso employed as master and Modigliani as spiritual dreamer.

But even all this could not satisfy that fever for activity, that fecund restlessness which at all times determined the tremendous productivity of Bakst. It was necessary, people were agreed, to offer, in opposition to the Academy of Fine Arts, managed by pedantic dilettants who were embittered by the triumph of the new art, a form of instruction at once free and sane. The haughty air of the Academy’s official staff was not justified either because of any venerable tradition nor because of the most elementary savoir faire. The “wanderers”, having dislodged from the Academy the pedants whom Bakst knew, placed themselves in their seats. Their æsthetic carelessness was complete, their ignorance of Western art absolute and provoking. At the same time young artists who rebelled at this teaching were reduced to the necessity of acquiring the rudiments of painting by themselves.

Affairs were in such a condition that they absolutely needed to be remedied. Bakst therefore associated himself with Mstislas Doboujinsky,{121}

a remarkable offspring of “Mir Iskousstva”, who excelled in the designing of the ornament and of the vignette, and who later worked with considerable success in the theater, in order to start a free school. I recall having been able, in connection with an exposition organized by the review “Apollo”, to estimate the results achieved during the first year of the school’s work. One series of studies symbolized a nude man on a{122} background of red material. There was none of that “academic” way of placing things in a vacuum or in a neutral atmosphere, nor of sketches colored amid gray shadows. The bright red of the background played upon the subject in green lights; the rhythm of the colored surfaces superimposed itself upon the anatomic harmony of the body. All these attempts were strictly anonymous as far as the public was concerned; it was not the personal pride of the students that was to be flattered; it was merely a question of establishing the validity of the method. That did not hinder the fact, however, that some of those young unknown painters today enjoy a reputation that borders upon renown.

We have now reached the year 1908. Bakst seems to have condensed his effort. He has summoned back the ancient legendary tale and has restored it to the theater. This myth he has also projected upon a famous canvas. In his portraits his incisive line closely encompasses material and internal realities. In his romantic dreams he has been able to live again through what Stéphane Mallarmé has called “la grâce des choses fanées”. Later he makes a division of his artistic property among his enthusiastic students. How much there is in this to fill a beautiful life! One might think that the circle of such men as Bakst is completed in one harmonious curve. But it is nothing of the sort.

Bakst is one of those men whose road is laid out in spiral form. What seems like a stop, is in fact nothing but a turn of the road. And at each turn the circle widens. At Petrograd his task is completed. There is nothing left there except to follow. But there remains Paris and the universe.

In reality, I am at the end of my task, which is that of acquainting the reader with a Bakst who has not yet been written up, of speaking of his formative period and of the intimate and hidden sources of his inspiration. Once my hero had entered upon public life, I ought already to have left the domain of his private existence. It is with regret that I take leave of the good little fellow who goes into ecstasy over his grandfather’s canary birds; of the uncompromising youth who defies his ignorant masters; of the young man who risks his future—and what a{123}

future!—for the sake of the exquisite form of a smile and the profile of a tapering hand; and finally of the artist whom I see in my country becoming identified with all big projects, either undertaking them or excelling in them.

But this study would perforce be incomplete if I did not decide to accompany our friend on his exodus toward the West and to put together the main facts of his recent activity which sends its rays over the entire world—an activity of which, for the most part, I am a witness.

Therefore, en route to Paris!{132}

A SHOW IN AN ARMCHAIR

In 1906 or thereabouts, following immediately upon the first Russian revolution that failed so grievously, the group of young artists and poets marched side by side through the breach that had been opened in the citadel of public opinion. The “modernists” of “Mir Iskousstva”, who had been jeered by the common herd, came into their own. But a certain uneasiness troubles this rising power; it feels itself incomplete, limited in a fatal manner. It is not equipped to reestablish great painting; it can only count upon illustrators, decorators, and poets of the{133}

past. And, as is the case with authority everywhere when it feels itself threatened, so too this group, not being able to assert itself, was anxious to spread out.{134}

Accordingly, they looked for new fields to conquer. Once again we see Diaghileff leading the attack. He releases that great exodus of Russians to the West—the brilliant and victorious march on Paris. The offensive starts with a Russian exhibition at the “Salon d’Automne”, an exhibition which under the guise of being retrospective is in reality a fighting manœuvre. A collection of icons, of numerous portraits of the eighteenth century symbolizes the return to a tradition which the young men of the “Monde Artiste” proclaim to be their own. Similarly the arbitrary gaps indicate their complete break with the unnatural art of the “wanderers”, the latter having been nearly entirely eliminated.

Bakst took part in this enterprise not alone as a painter. He decorated the hall of the eighteenth century, which had been transformed into a grove, with a trellis surmounted by vases. This conception of an exposition hall forming an organic whole, making a coherent ensemble, and therefore having a distinctive atmosphere—is not this, again, a gift belonging to the Russians?