.

With an Appendix by Otto Sverdrup Captain of the Fram

In two volumes

Vol. II.

New York and London

Harper & Brothers Publishers

Contents of Vol. II.

- Chap. Page

- I. We Prepare for the Sledge Expedition 1

- II. The New Year, 1895 41

- III. We Make a Start 90

- IV. We Say Good-bye to the “Fram” 132

- V. A Hard Struggle 157

- VI. By Sledge and Kayak 236

- VII. Land at Last 308

- VIII. The New Year, 1896 454

- IX. The Journey Southward 487

Appendix

- Report of Captain Otto Sverdrup on the Drifting of the “Fram” from March 14, 1895.

- I. March 15 to June 22, 1895 601

- II. June 22 to August 15, 1895 633

- III. August 15 to January 1, 1896 648

- IV. January 1 to May 17, 1896 668

- V. The Third Summer 683

- Conclusion 707

- Index 715

[vii]

Illustrations in Vol. II.

- Page

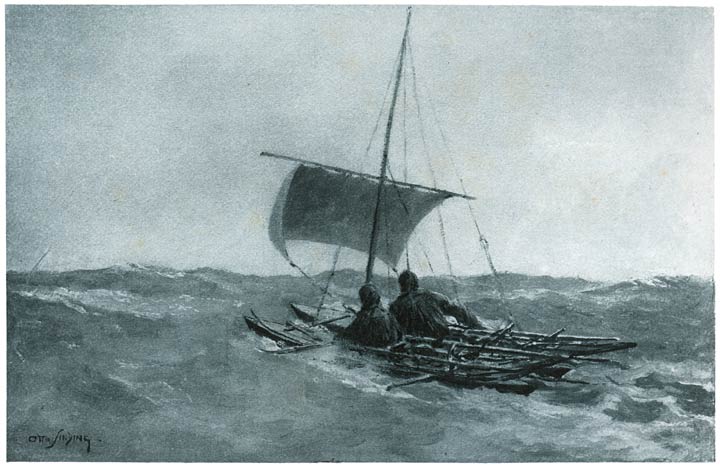

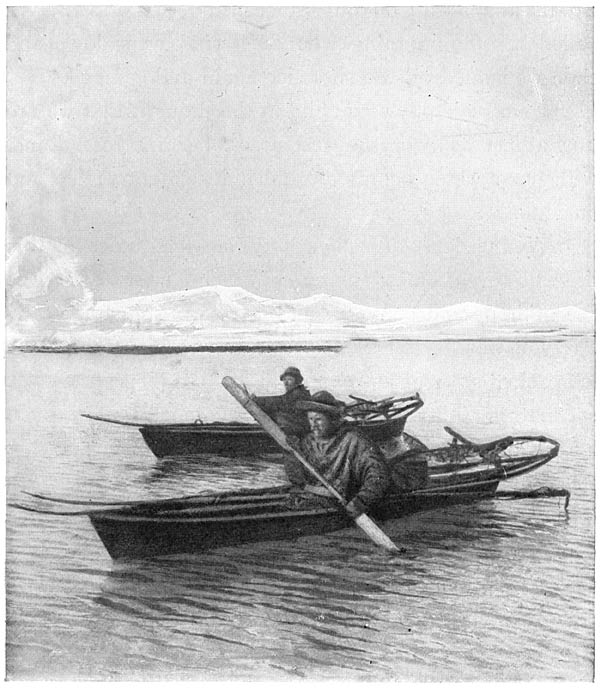

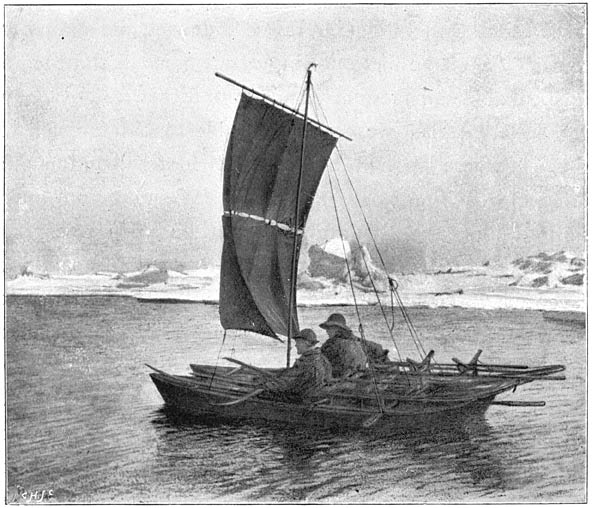

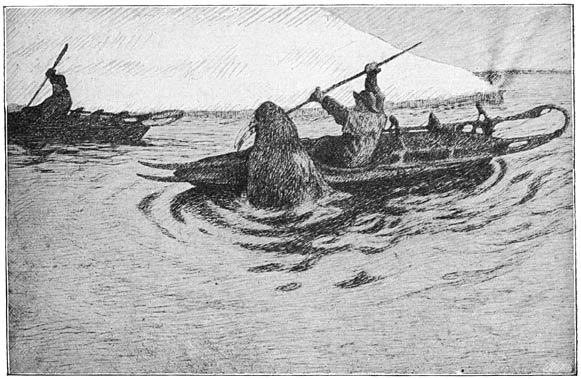

- Sailing Kayaks (Photogravure) Frontispiece

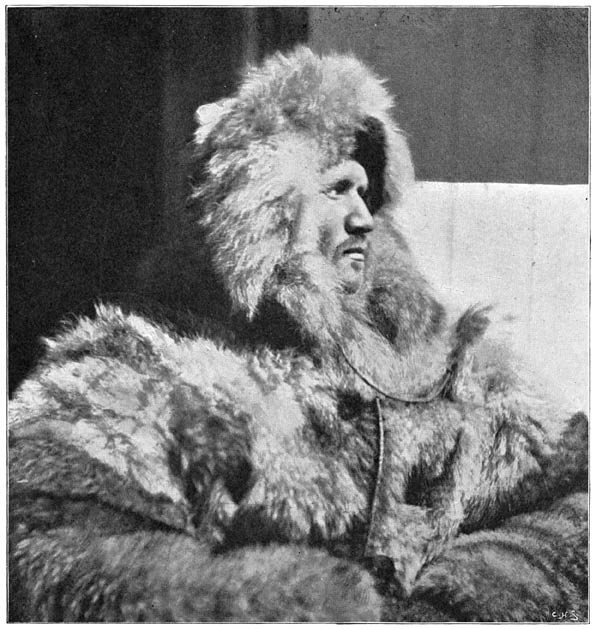

- Hjalmar Johansen Facing p. 2

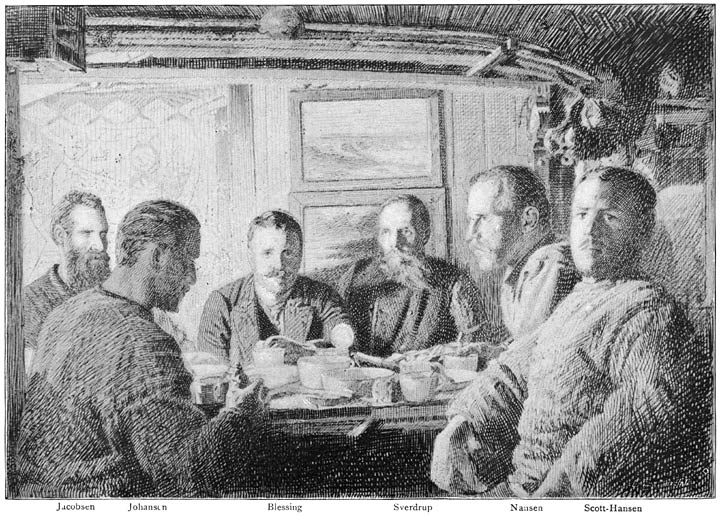

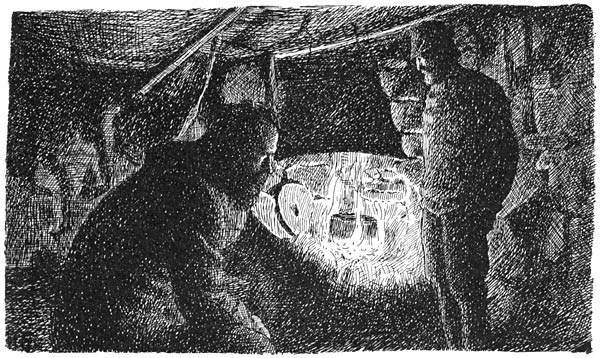

- At the Supper-table (February 14, 1895) 9

- Scott-Hansen’s Observatory 17

- Musical Entertainment in the Saloon 35

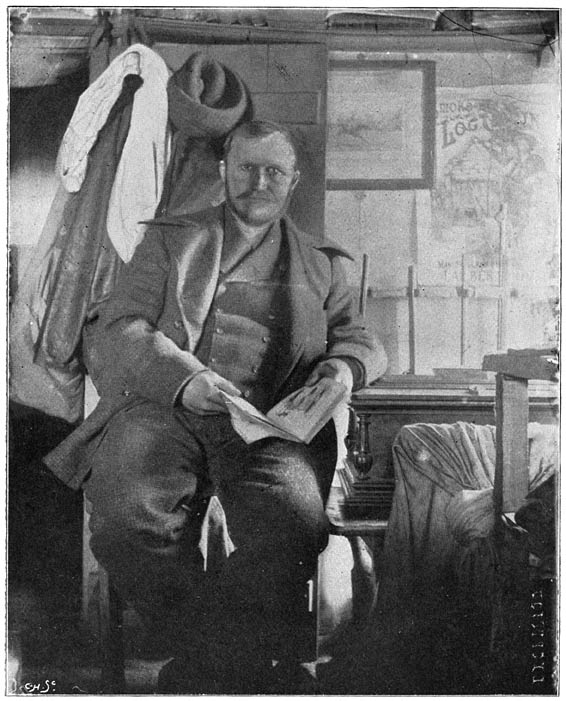

- Captain Sverdrup in His Cabin 49

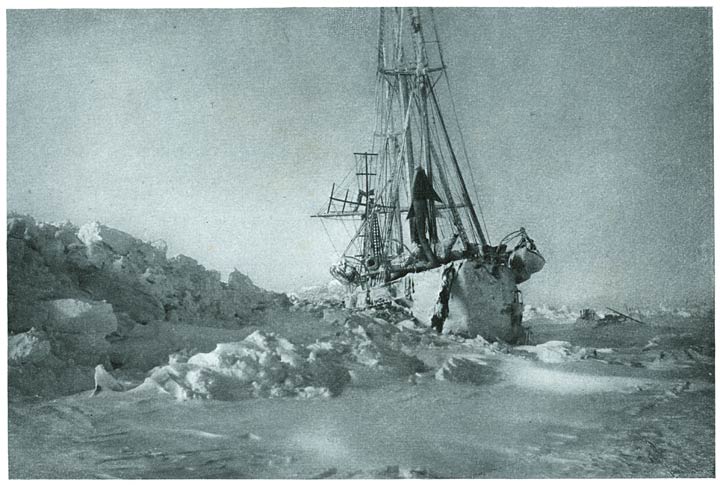

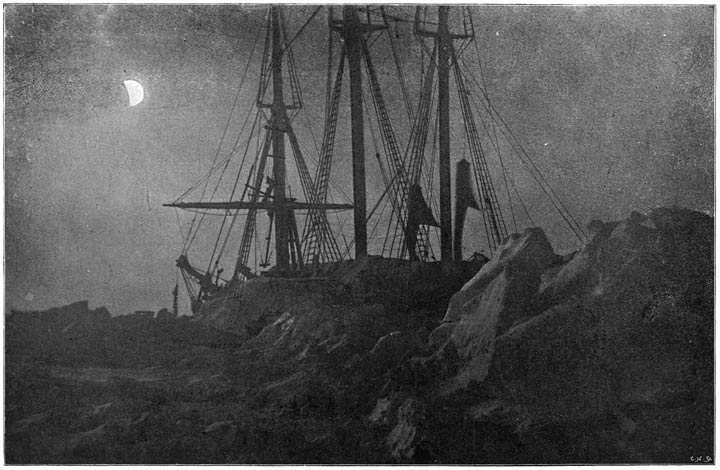

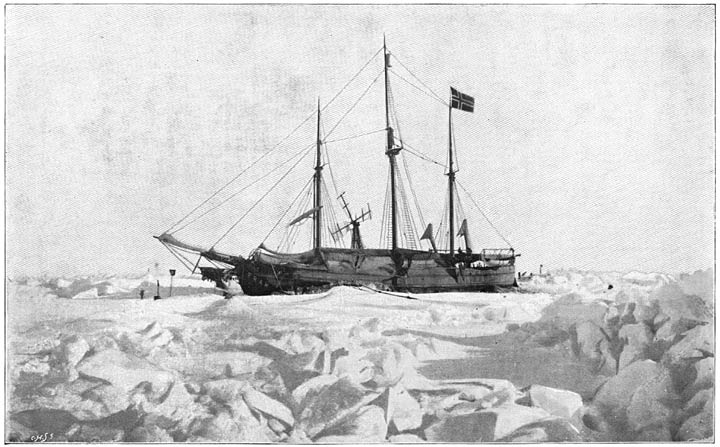

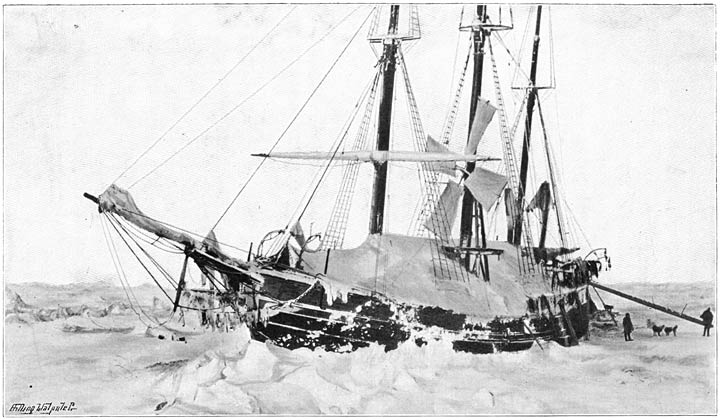

- The “Fram” in the Ice (Photogravure) Facing p. 54

- “All Hands on Deck!” 56

- “A Most Remarkable Moon” 65

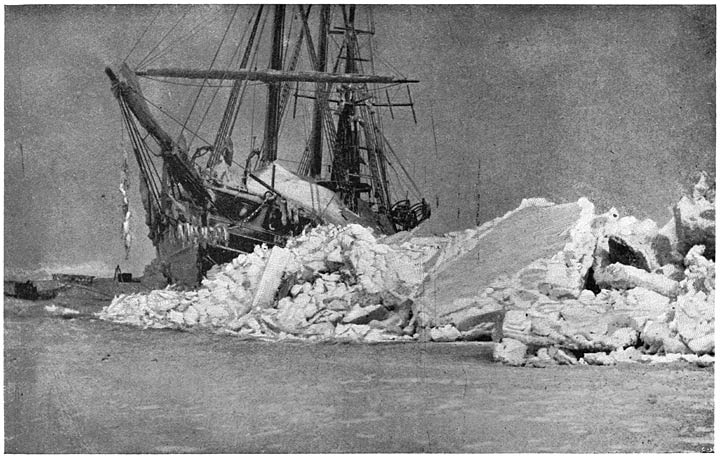

- The “Fram” After an Ice-pressure (January 10, 1895) 67

- The Winter Night (January 14, 1895) 71

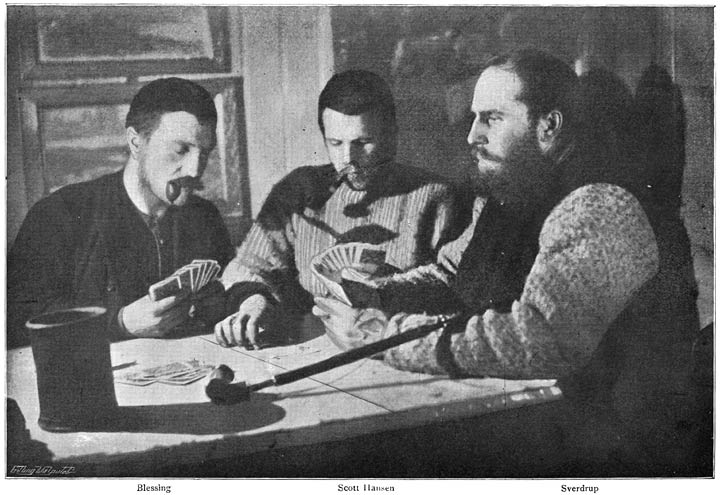

- A Whist-party in the Saloon (February 15, 1895) 79

- Upper End of the Supper-table (February 15, 1895) 83

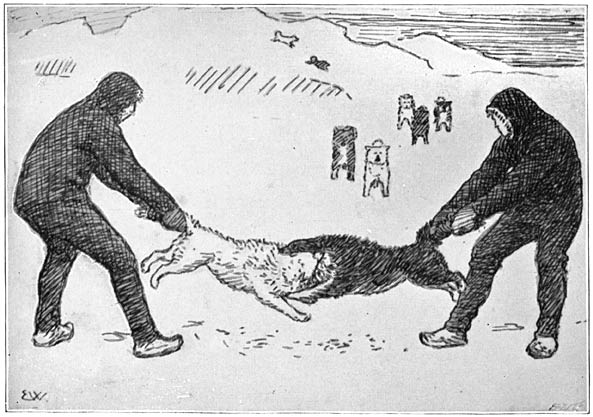

- Stopping a Dog-fight 85

- Lower End of Supper-table 87

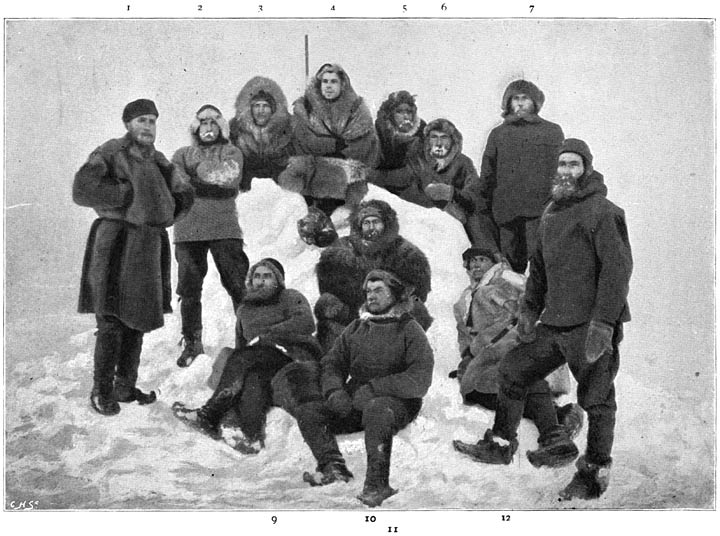

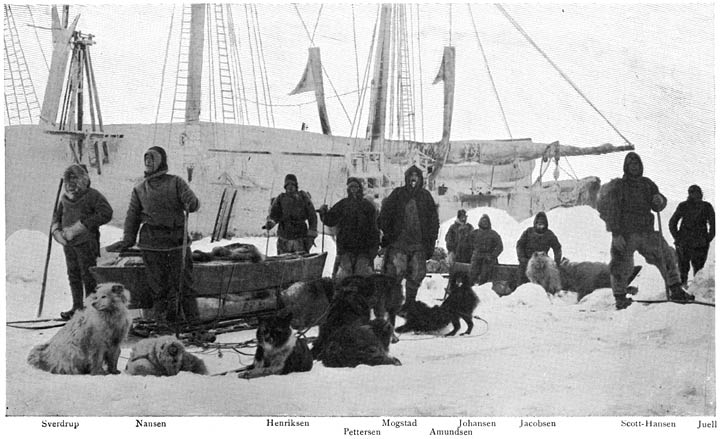

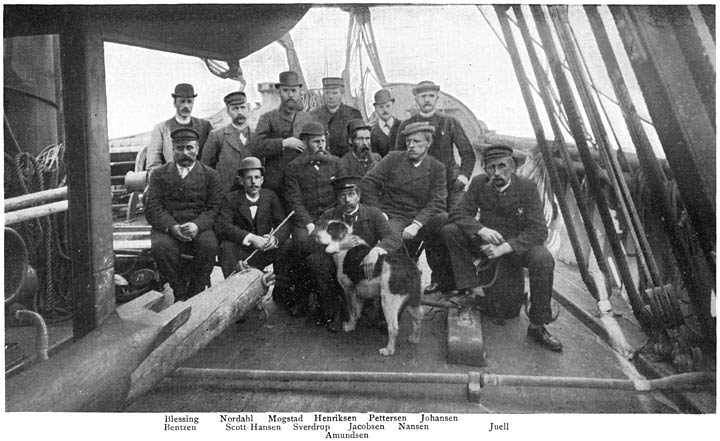

- The Crew of the “Fram” after Their Second Winter (About February 24, 1895) 93

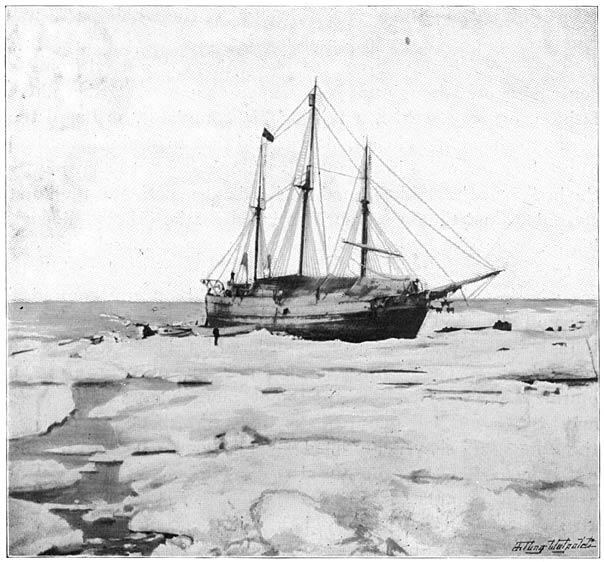

- The “Fram” in the Ice (1895) 103

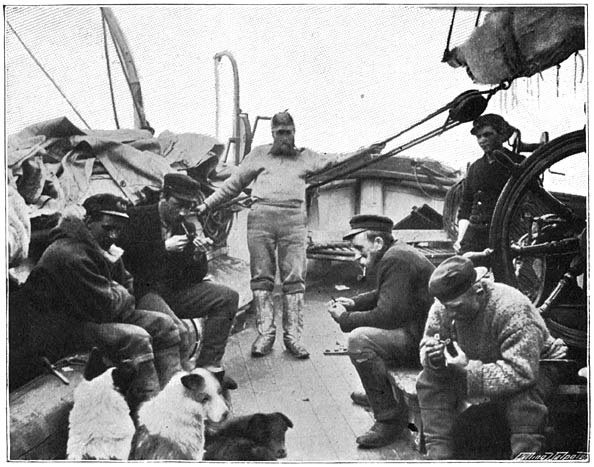

- Sunday Afternoon on Board 107

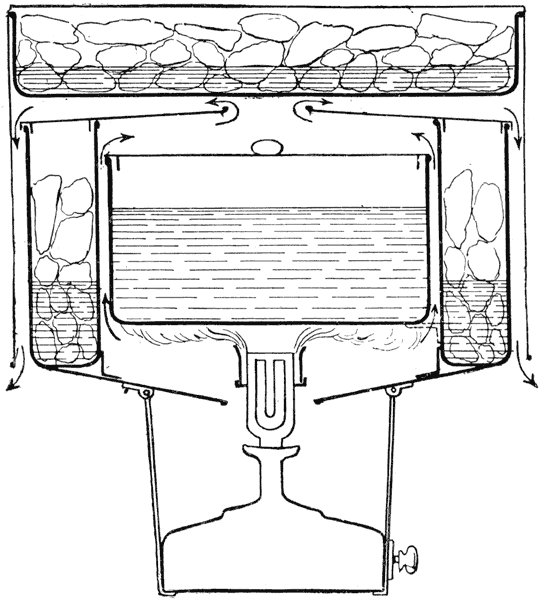

- The Cooking Apparatus 122

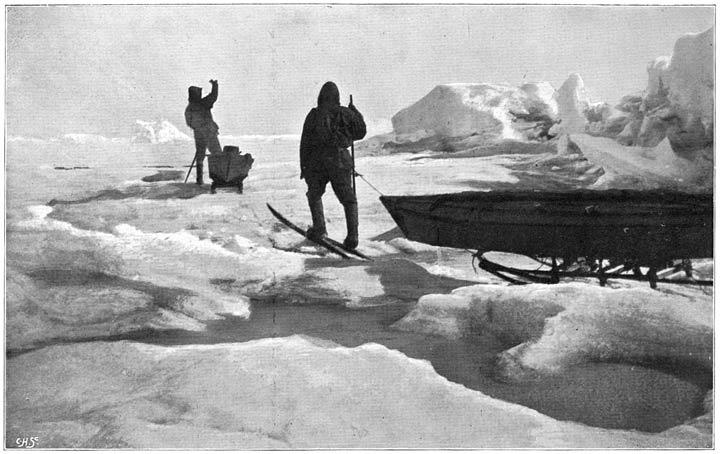

- The Start from the “Fram” (March 14, 1895) 133

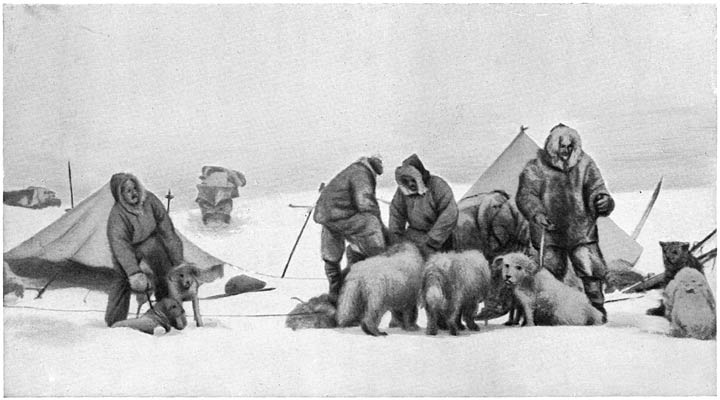

- Our Last Camp before Parting from Our Comrades 137

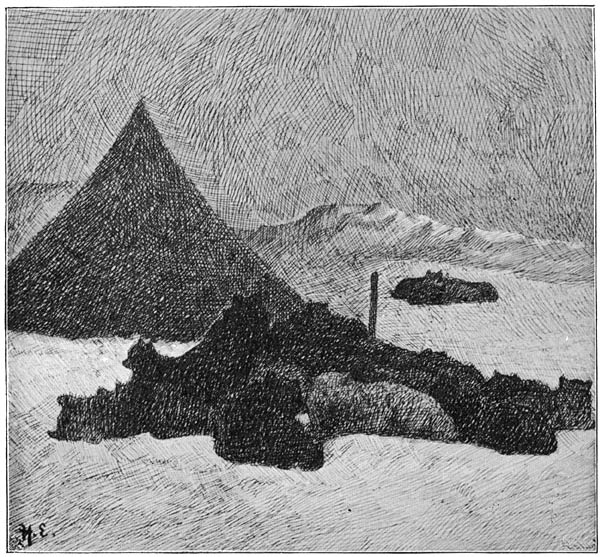

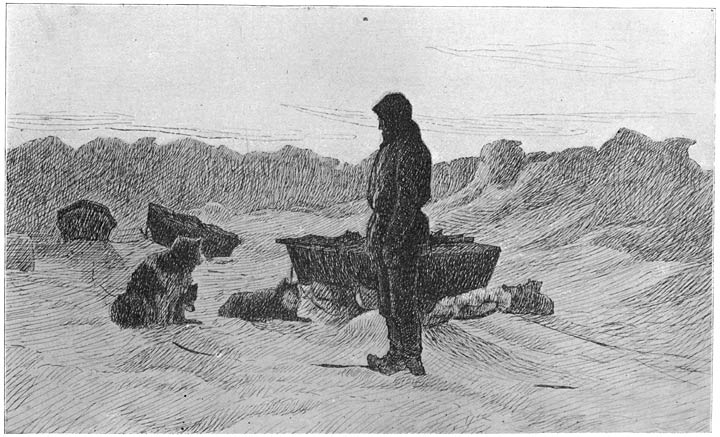

- A Night Camp on the Journey North 154

- Tailpiece 156

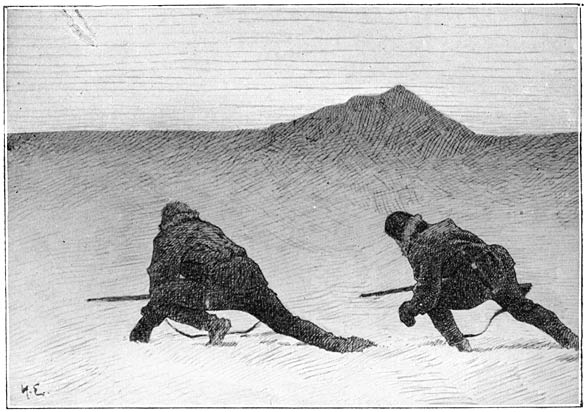

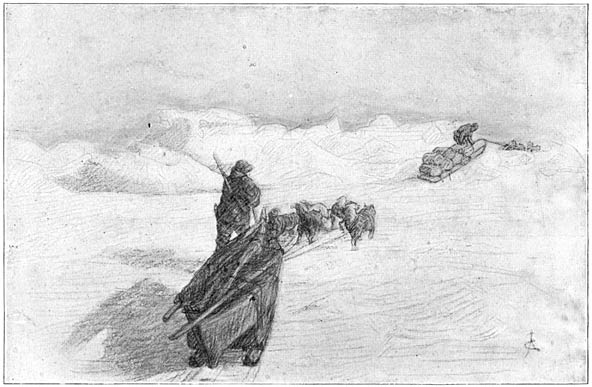

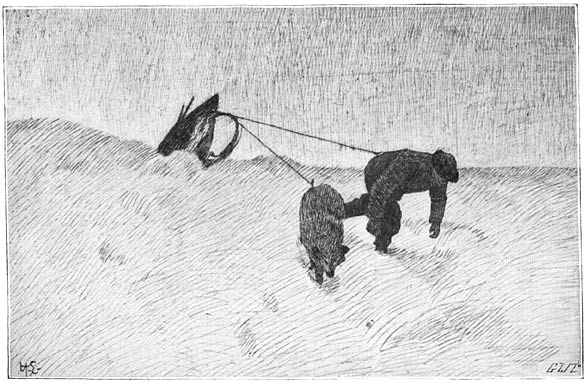

- Northward through the Drift-snow (April, 1895) 159

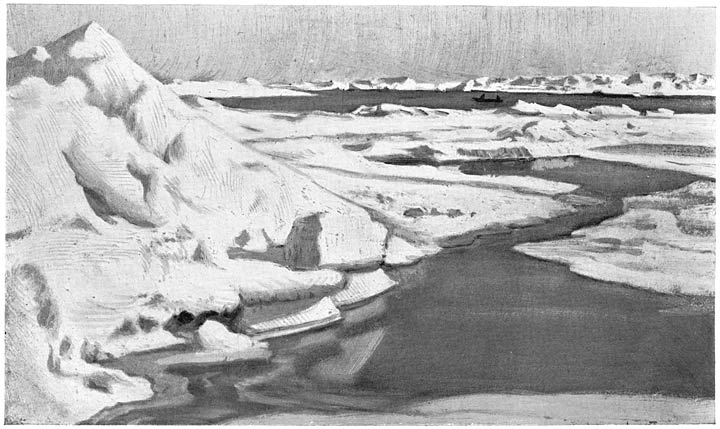

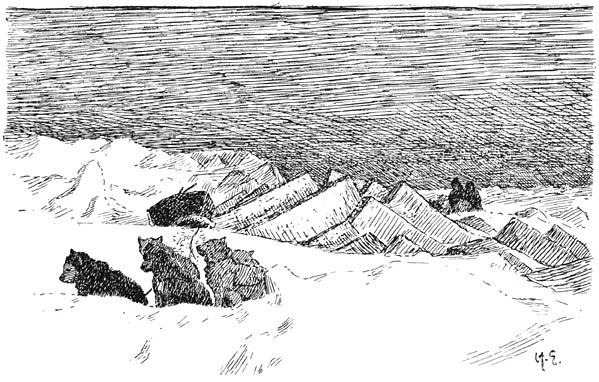

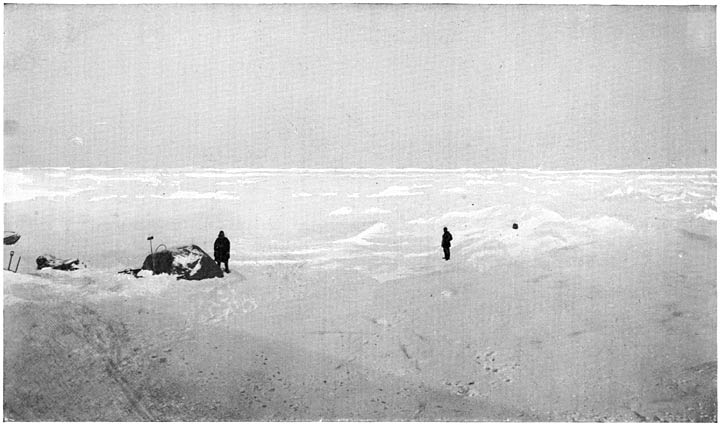

- Nothing but Ice, Ice to the Horizon (April 7, 1895) Facing p. 162[viii]

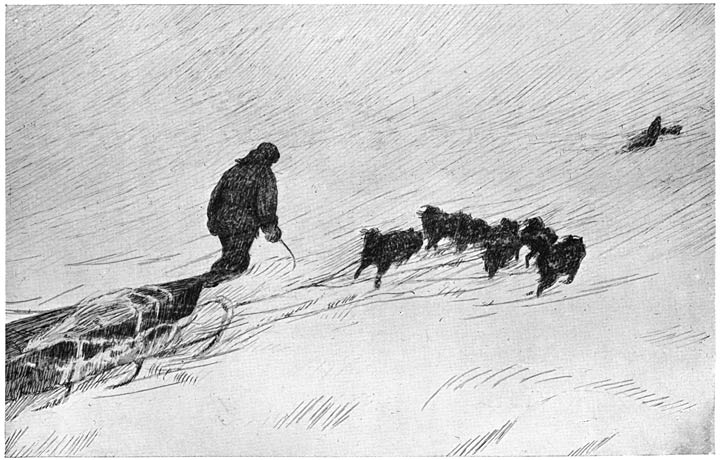

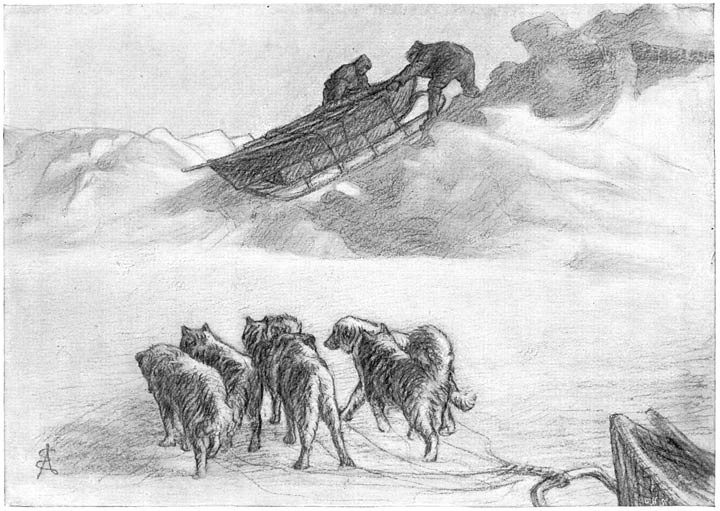

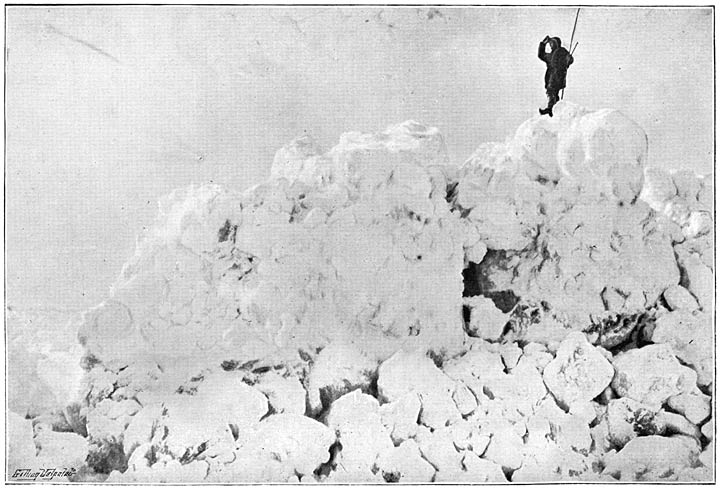

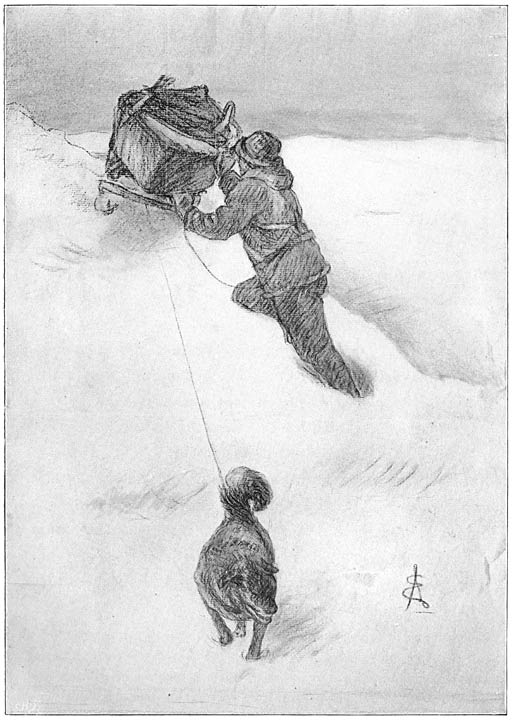

- Over Difficult Pressure-mounds (April, 1895) 165

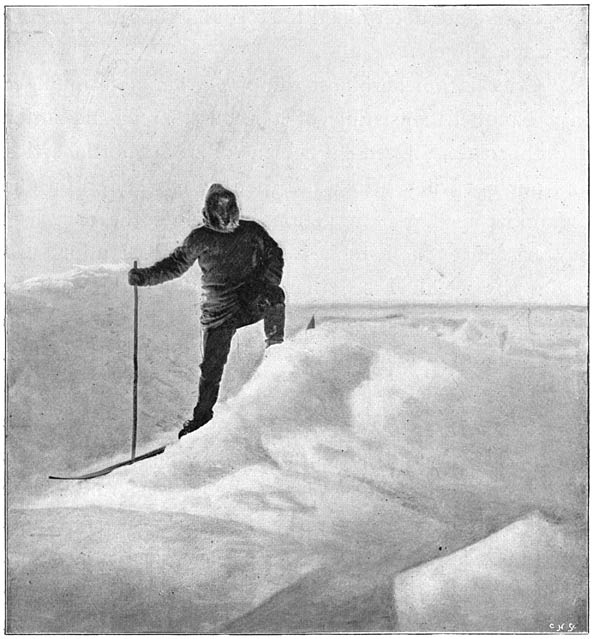

- “I Went on Ahead on Snow-shoes” 169

- “On Tolerably Good Ground” 171

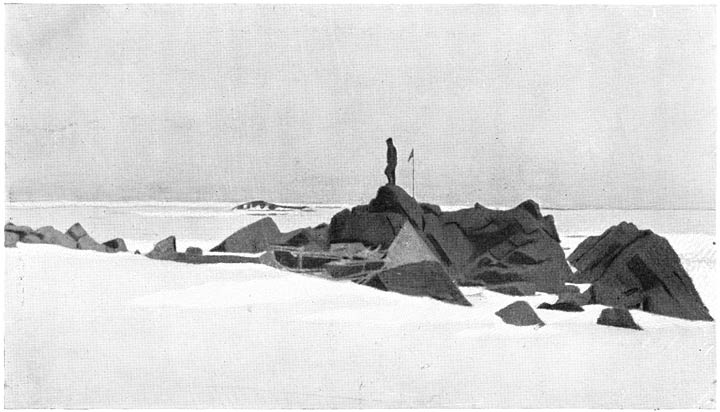

- Our Northernmost Camp, 86° 13.6′ N. Lat. (April 8, 1895) 173

- “Baro,” the Runaway Facing p. 178

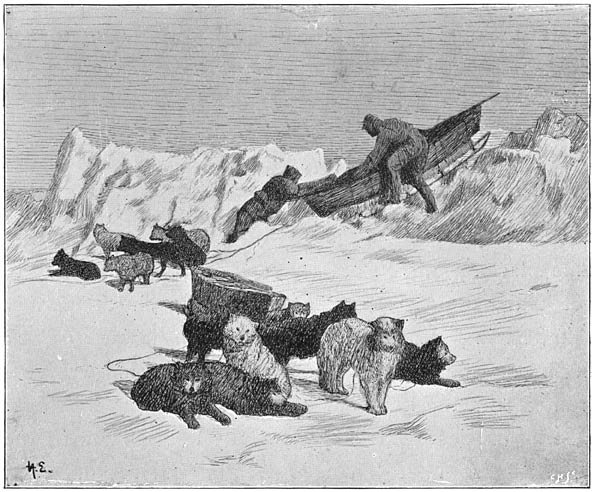

- Rest (April, 1895) 181

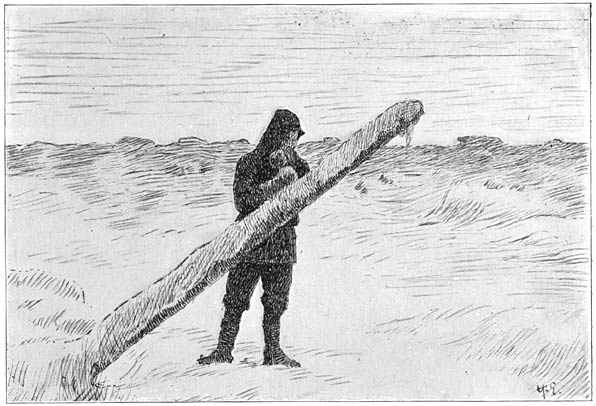

- Johansen Carving our Names in a Stock of Driftwood 185

- Peculiar Ice Stratification (April, 1895) 187

- “We Made Fairly Good Progress” 203

- Repairing the Kayaks 240

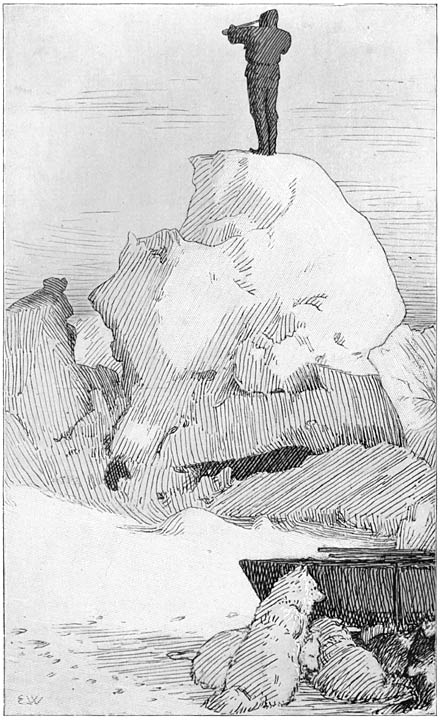

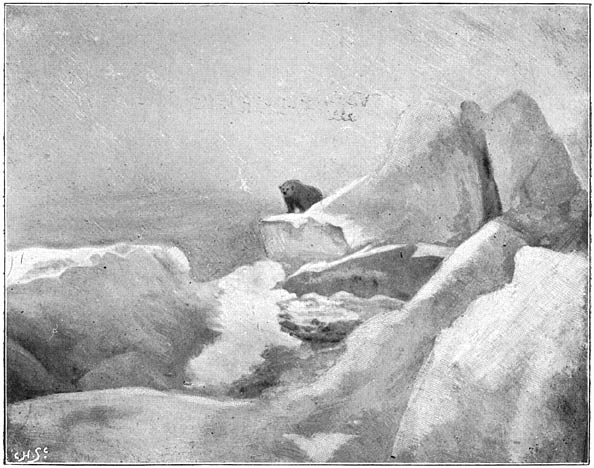

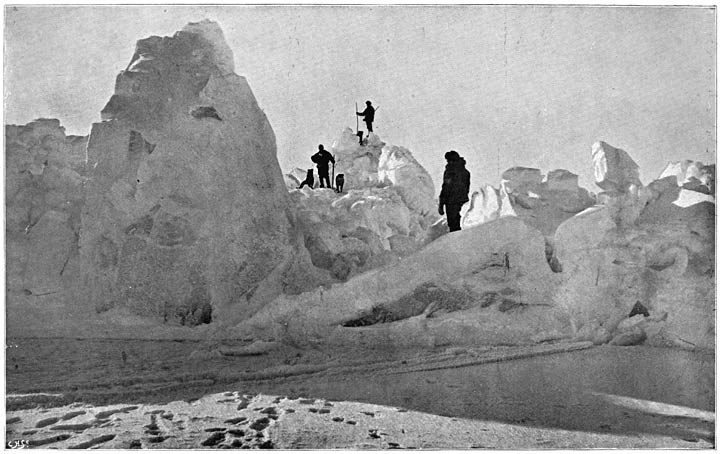

- A Coign of Vantage. Packed Ice 251

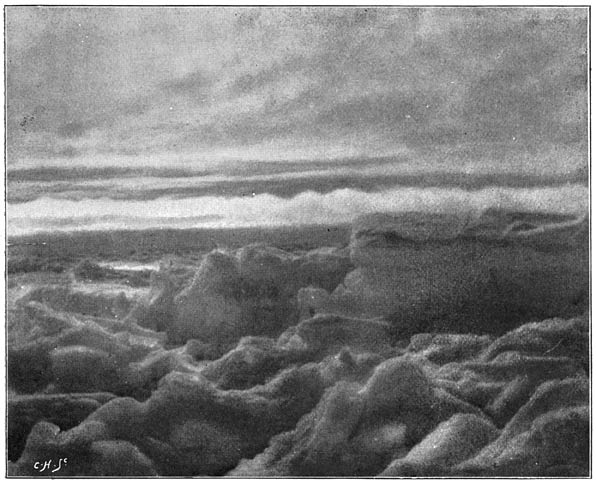

- “A Curdled Sea” 257

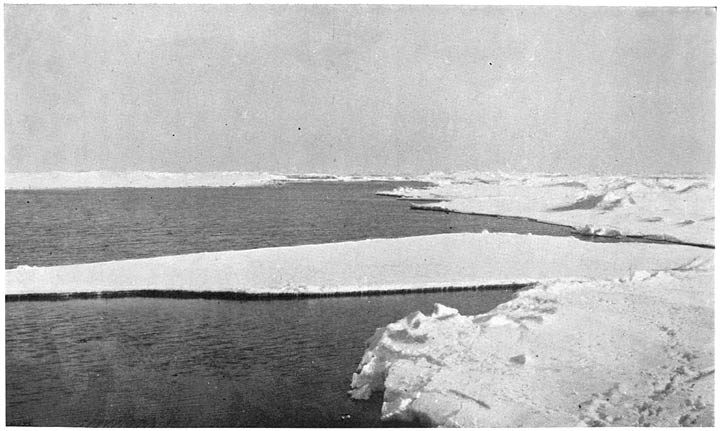

- Channels in the Ice in Summer (june, 1895) 263

- “Suggen.” “Kaifas” 277

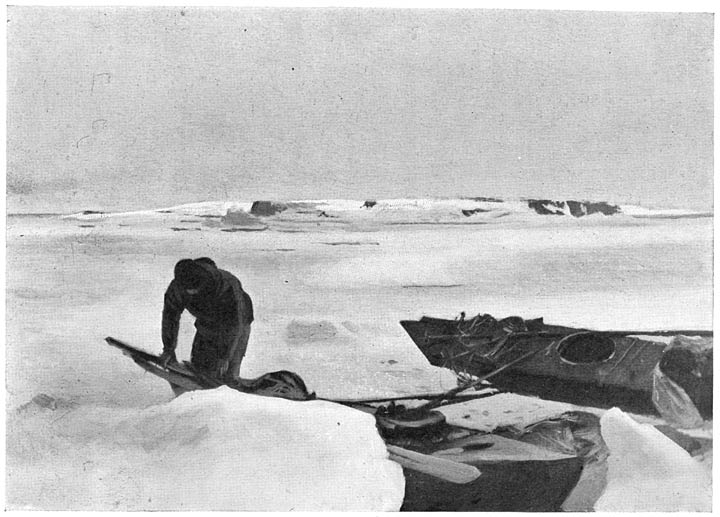

- Crossing a Crack in the Ice 287

- Johansen Sitting in the Sleeping-bag in the Hut 293

- Channels in the Ice (June 24, 1895) 297

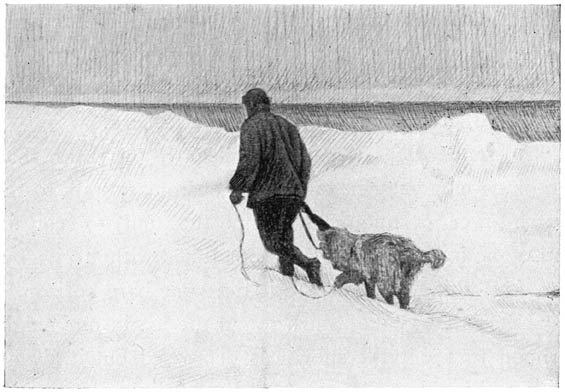

- My Last Dog, “Kaifas” 307

- “Incredibly Slow Progress” 323

- “This Inconceivable Toil” 327

- “You Must Look Sharp!” 330

- We Reach the Open Water (August 6, 1895) 337

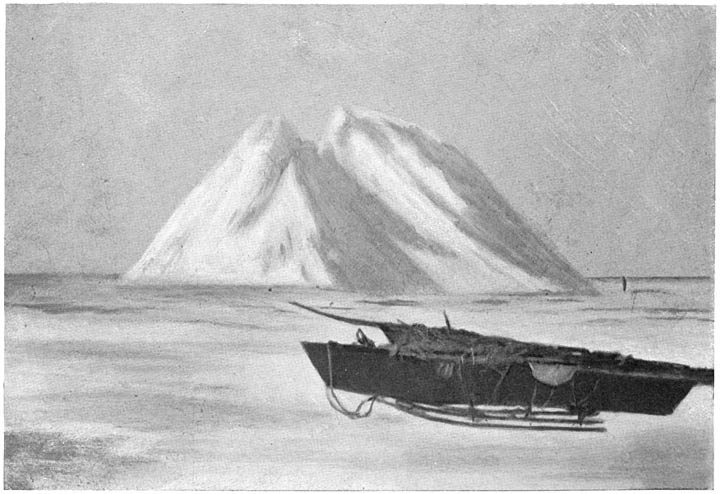

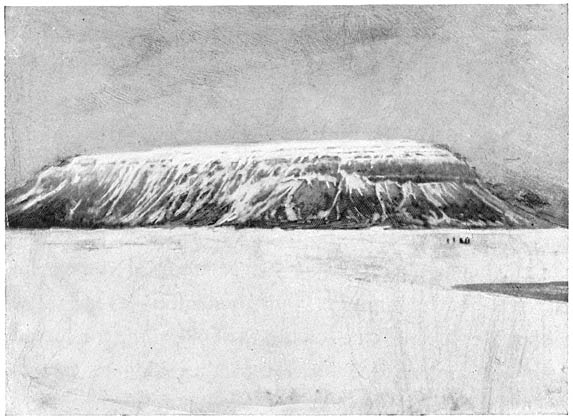

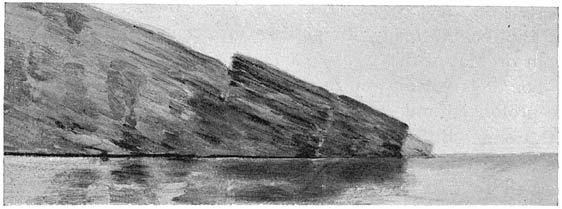

- Iceberg on the North Side of Franz Josef Land 351

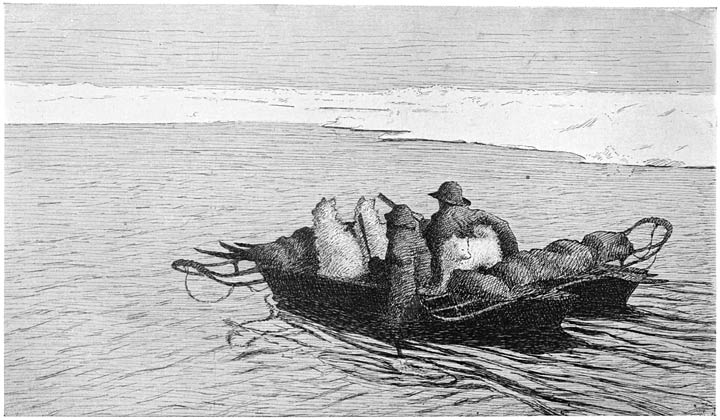

- A Paddle along the Edge of the Ice 359

- Glazier—Franz Josef Land 361

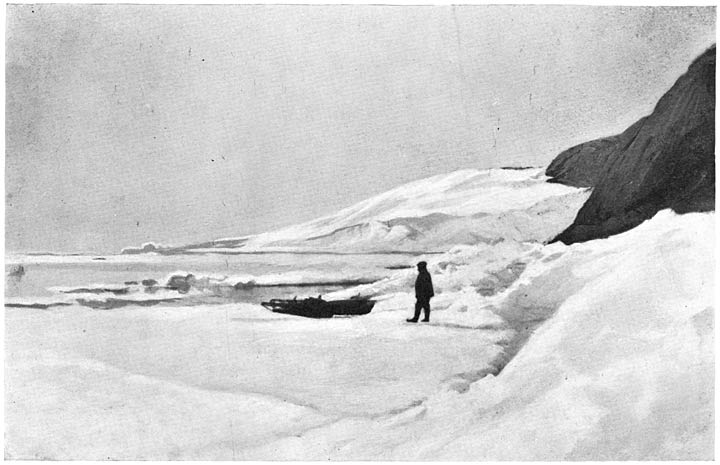

- A Camp on the Coast of Franz Josef Land 367

- Crack in the Ice 375

- “Sailing along the Coast” 378

- A Fight against the Storm to Reach Land (August 29, 1895) 381

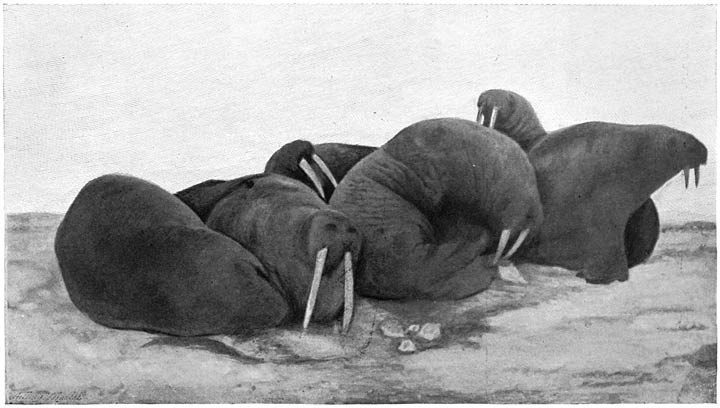

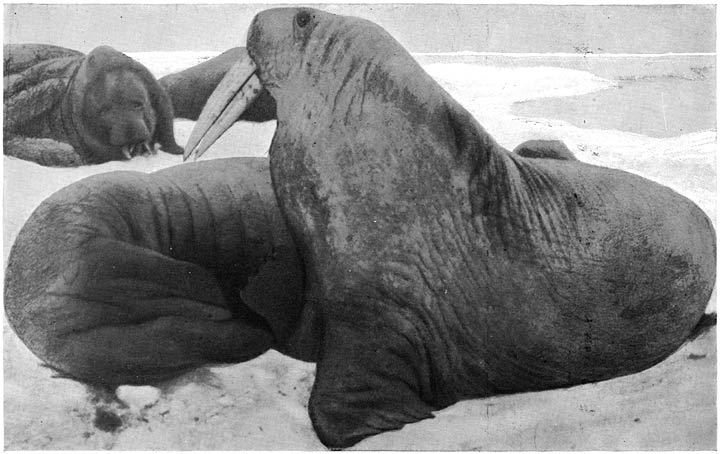

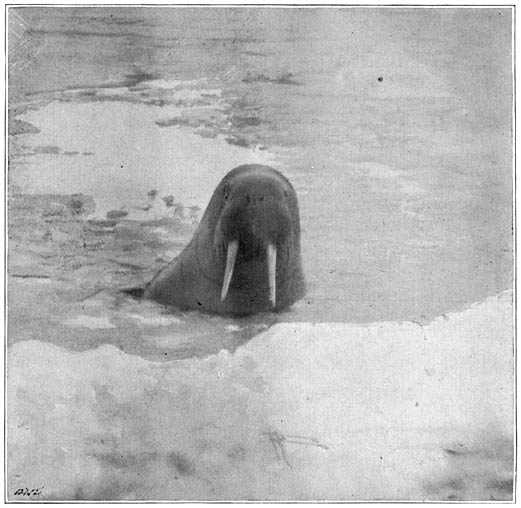

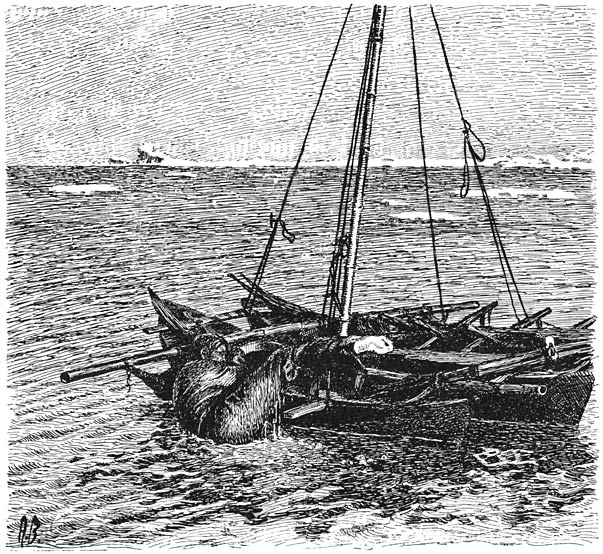

- Walruses 387

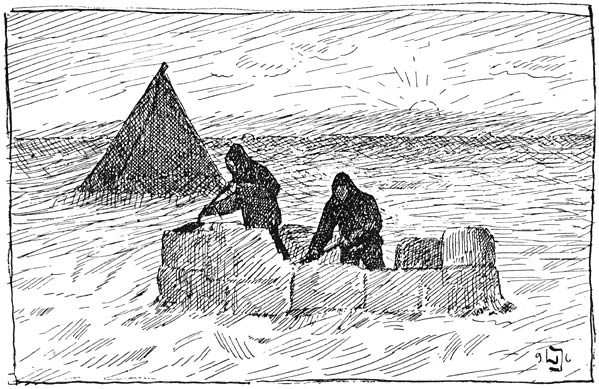

- We Build Our First Hut 390[ix]

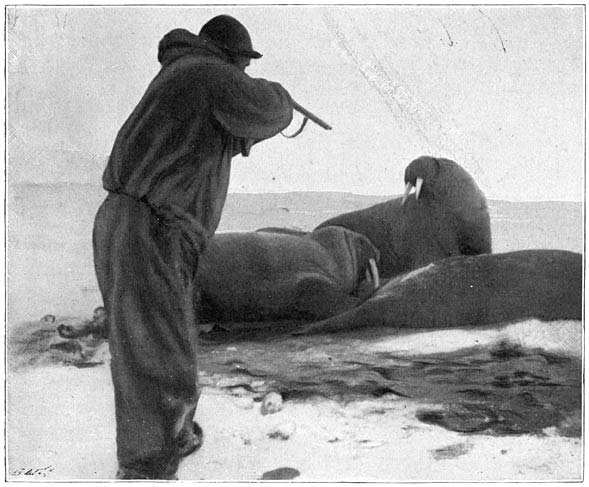

- Walruses 397

- “In the Water Lay Walruses” 409

- “I Photographed Him and the Walrus” 417

- “It Gazed Wickedly at Us” 419

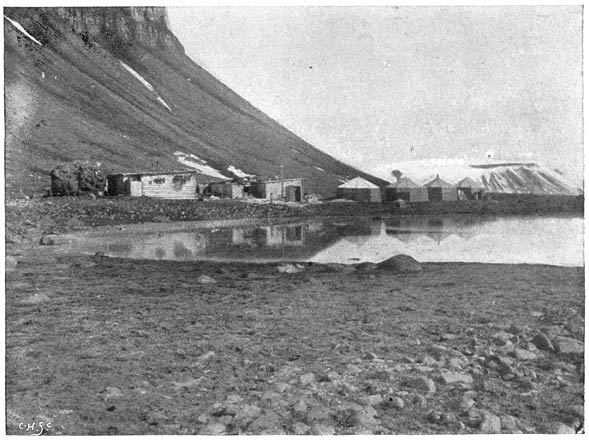

- At Our Winter Quarters 431

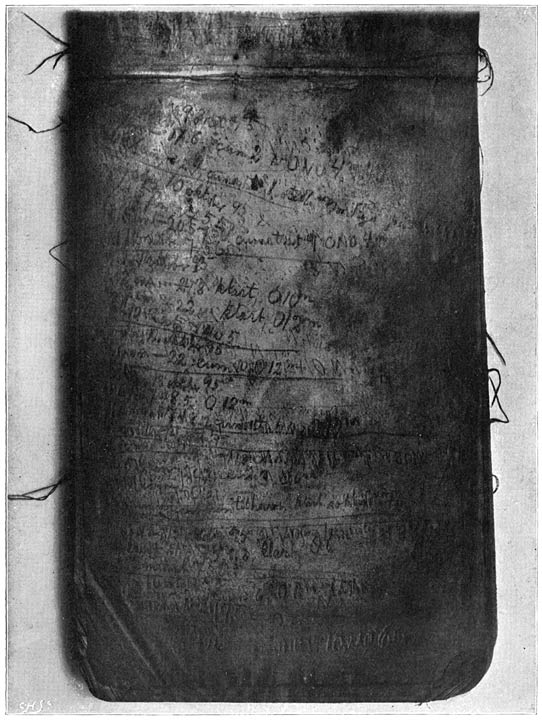

- An Illegible Page from Diary 437

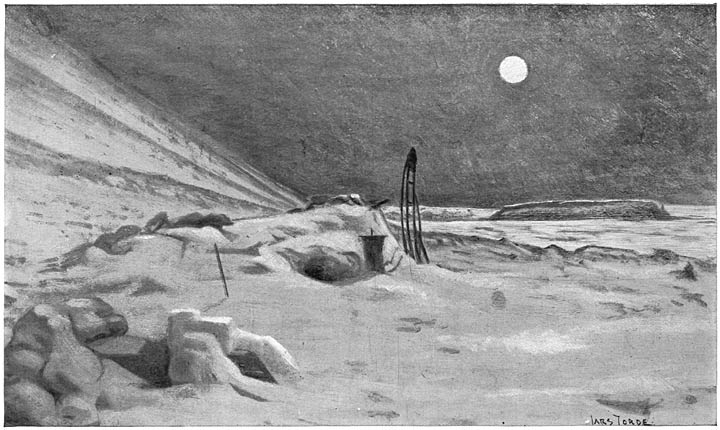

- Our Winter Hut (December 31, 1895) 451

- “Life in Our Hut” 456

- “Johansen Fired through the Opening” 468

- “Our Winter Lair” 489

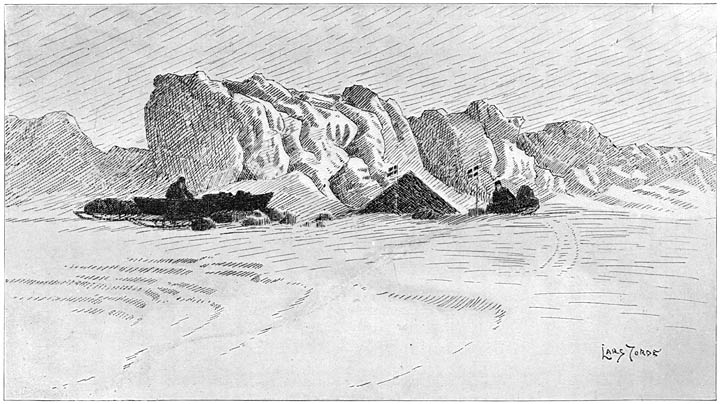

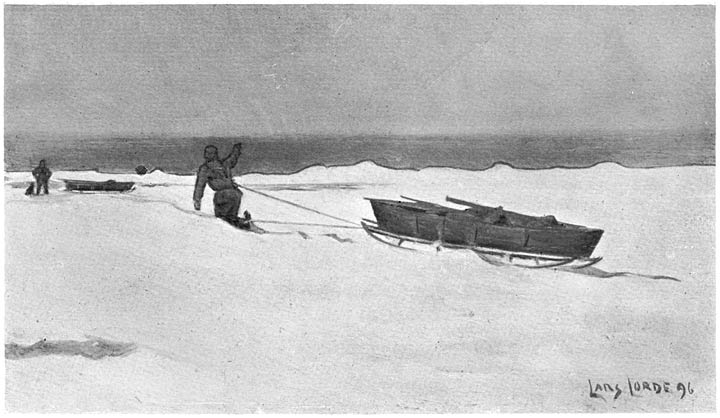

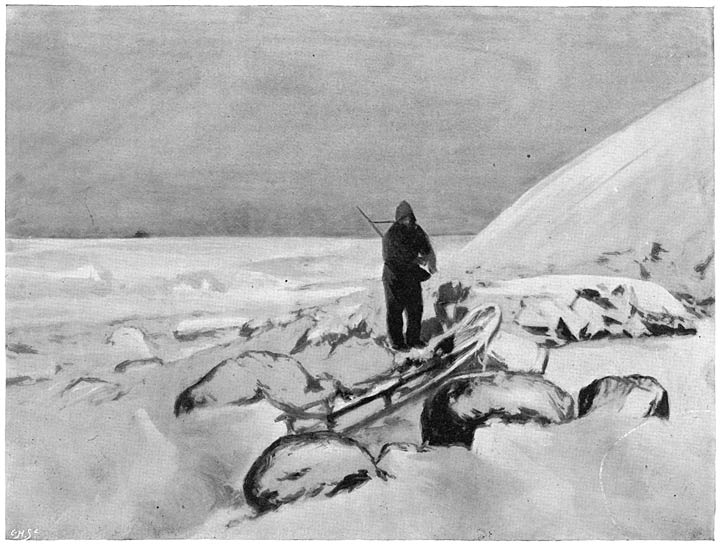

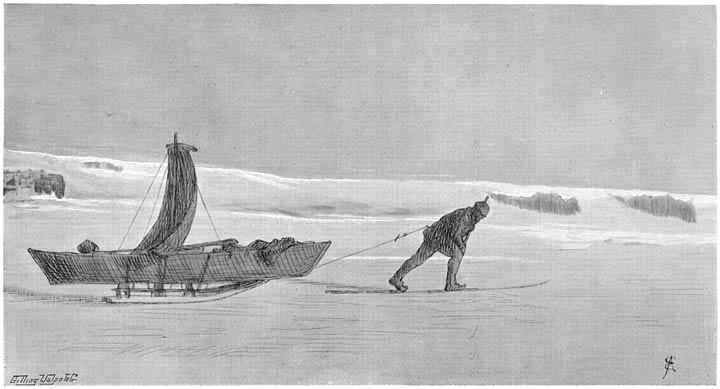

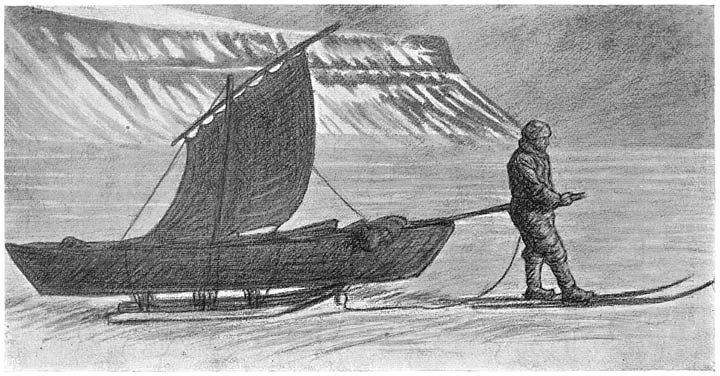

- Southward (May, 1896) 491

- Over the Ice towards the Island (May, 24, 1896) 495

- A Sail with Sledges. South of Cape Richthofen (June 6, 1896) 507

- “I Managed to Swing One Leg Up” 515

- “It Tried to Upset Me” 520

- Our Last Camp 523

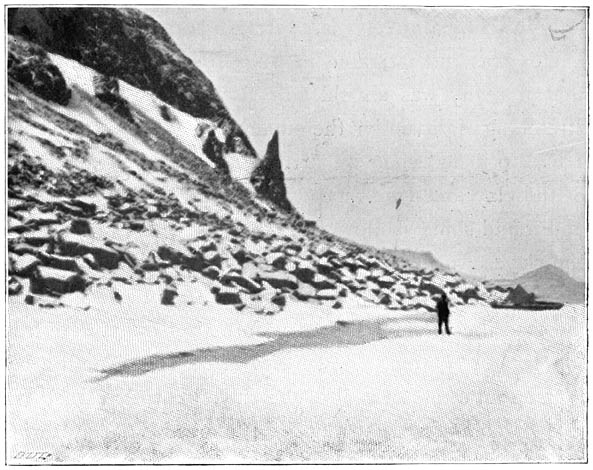

- Franz Josef Land 528

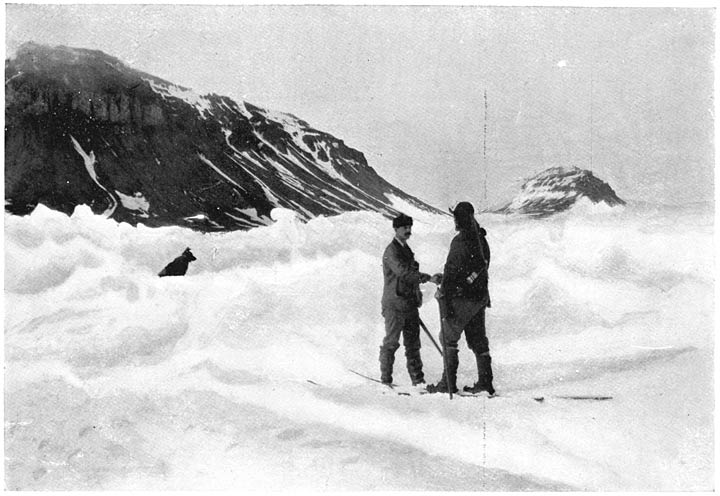

- Meeting of Jackson and Nansen 531

- Mr. Jackson’s Station at Cape Flora 535

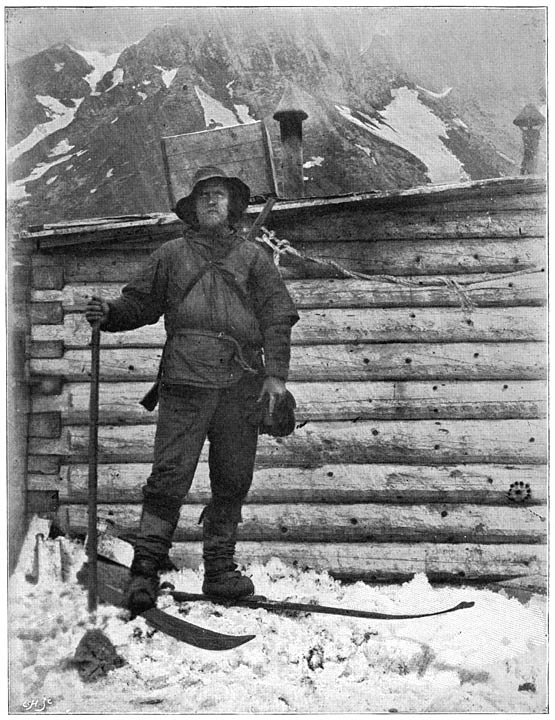

- Nansen at Cape Flora 537

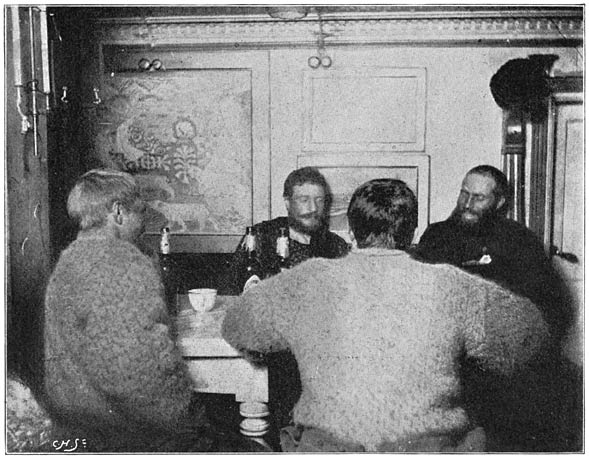

- A Chat after Dinner 541

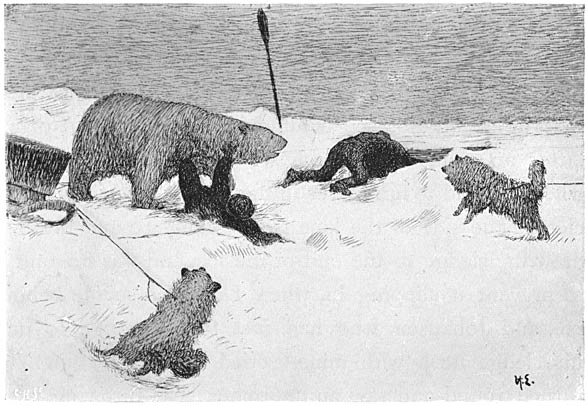

- The Wounded Bear 543

- Johansen at Cape Flora 545

- A Visitor 547

- Jackson on Cape Flora 551

- Basaltic Rock 554

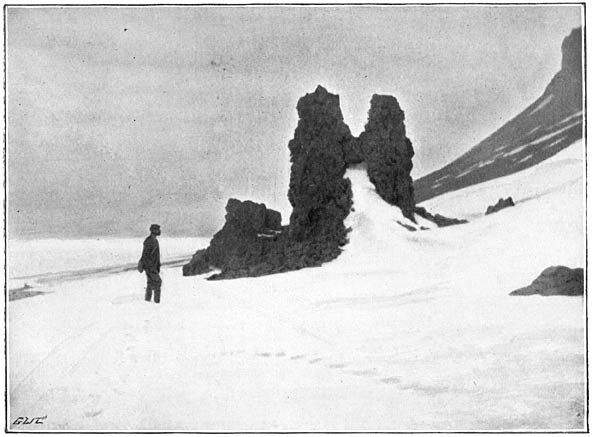

- A Strange Rock of Basalt 559

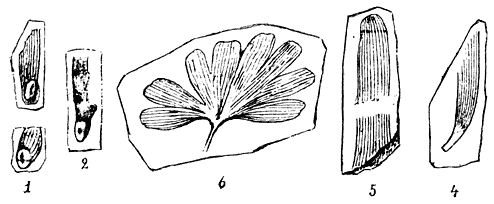

- Plant Fossils 561

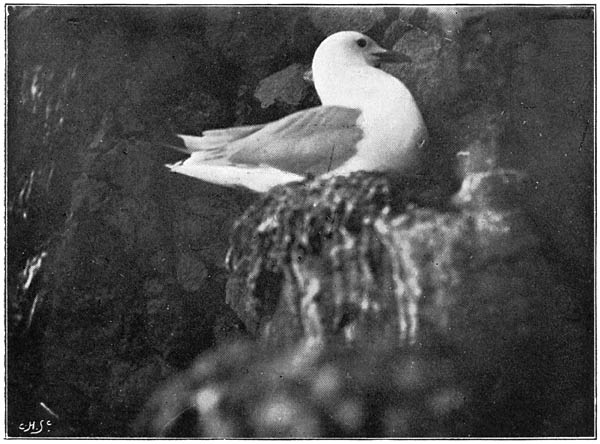

- Kittiwake on Her Nest 565

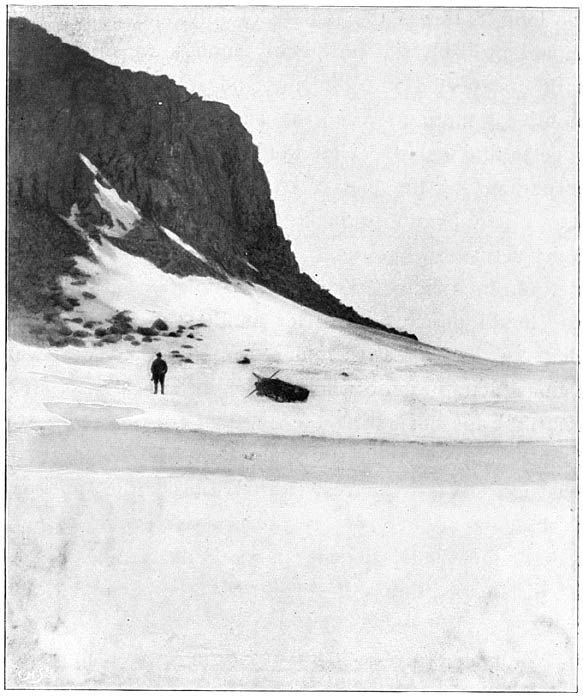

- Basaltic Cliffs 567

- Mr. Jackson at Elmwood 569

- Johansen in Jackson’s Saloon 571

- Cape Flora. Farewell to Franz Josef Land 577[x]

- “We Stood Looking over the Sea” 580

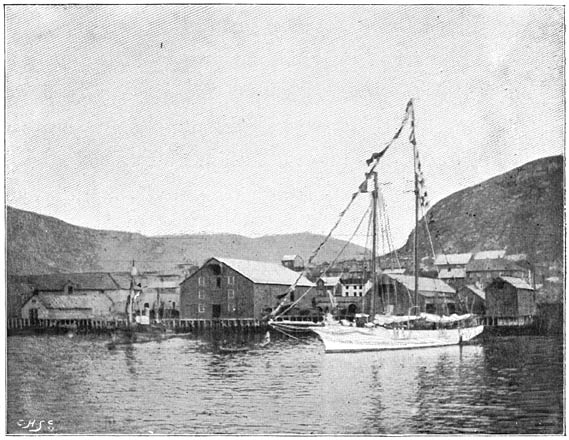

- Arrival at Hammerfest 587

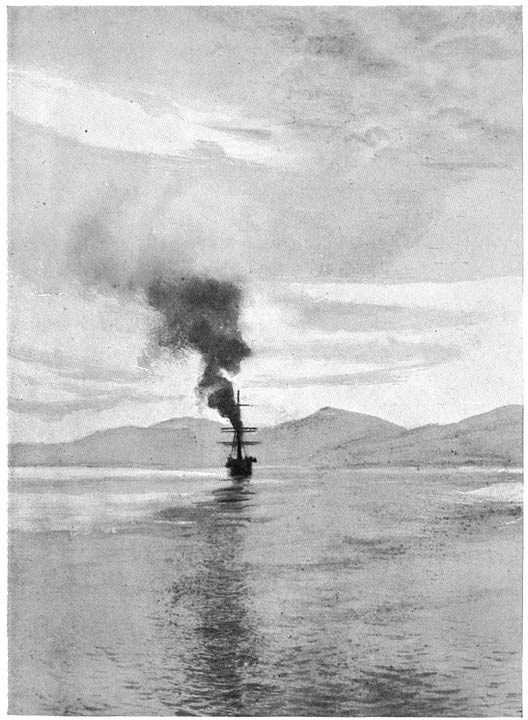

- The “Windward” Leaving Tromsö 591

- Tailpiece 597

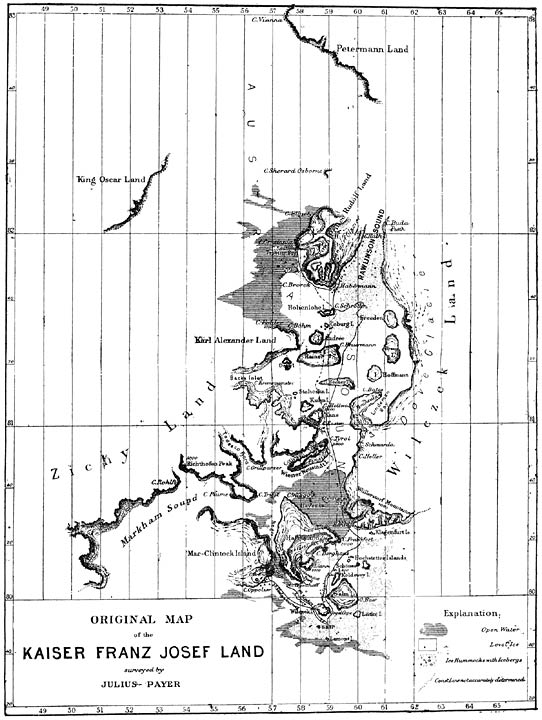

- Original Map of Kaiser Franz Josef Land 599

Appendix

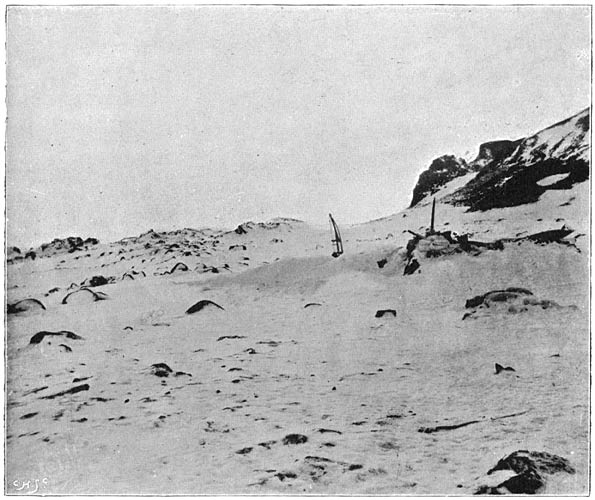

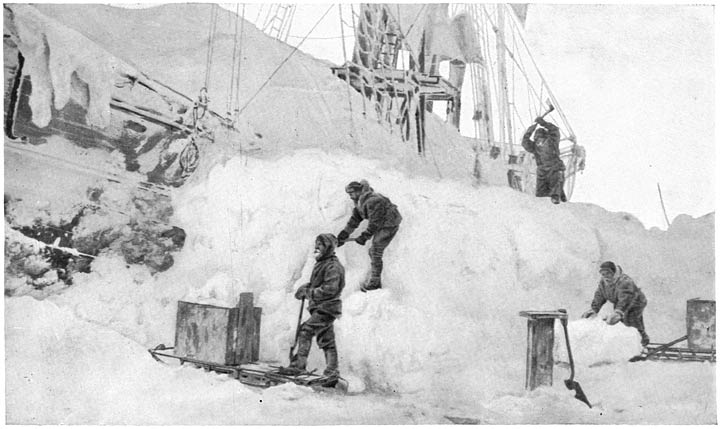

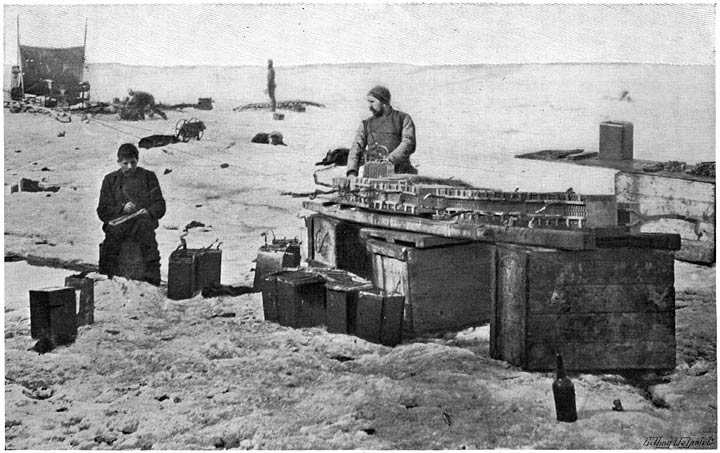

- Digging Out the “Fram” (March, 1895) 603

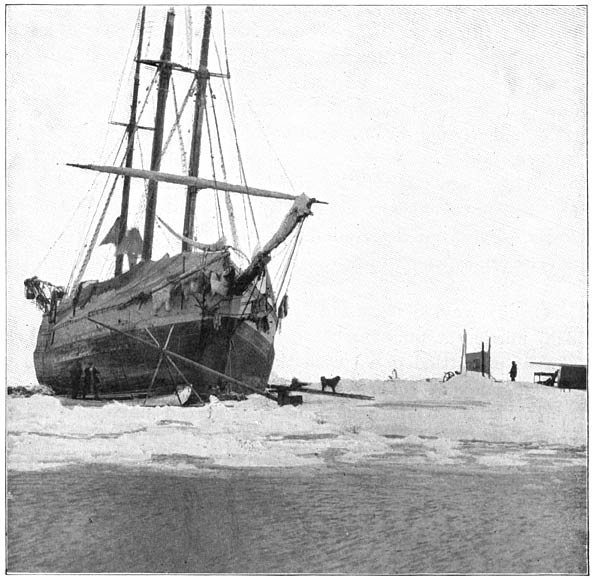

- The “Fram” when Dug Out of the Pressure-mound at the End of March, 1895 607

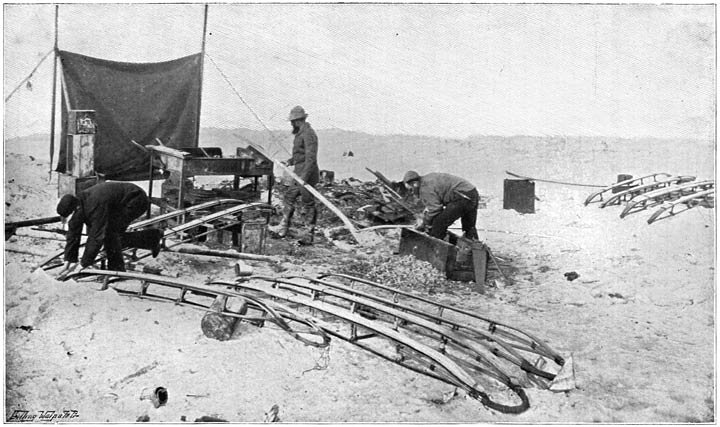

- Fitting the Hand-sledges with Runners (July, 1895) 611

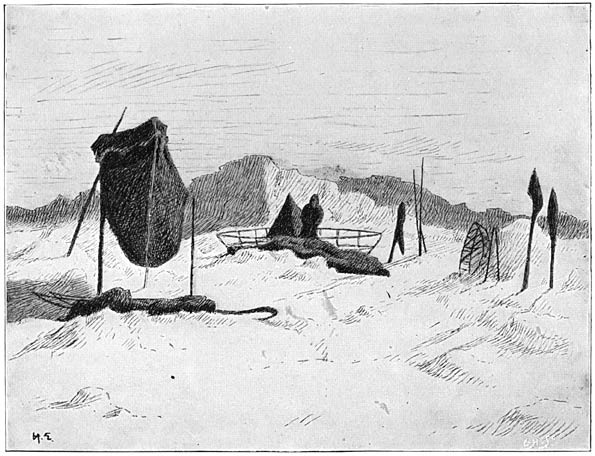

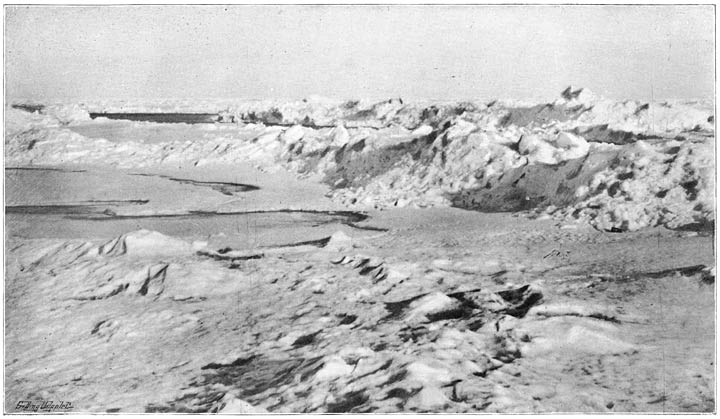

- View over the Drift-ice. Depot in Foreground 615

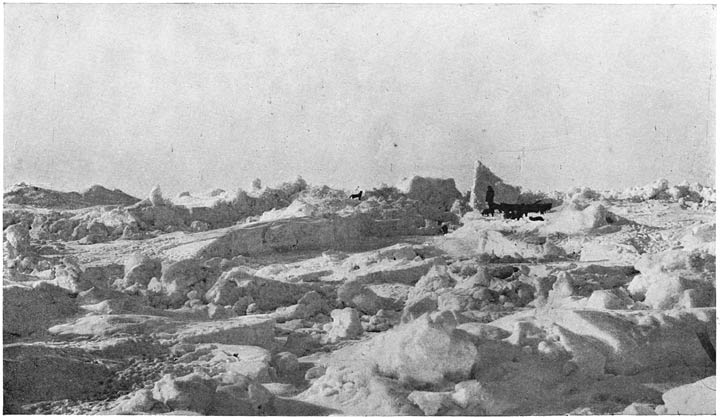

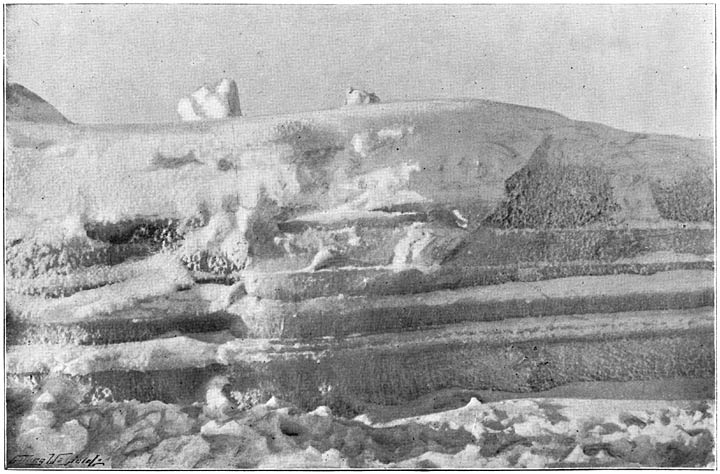

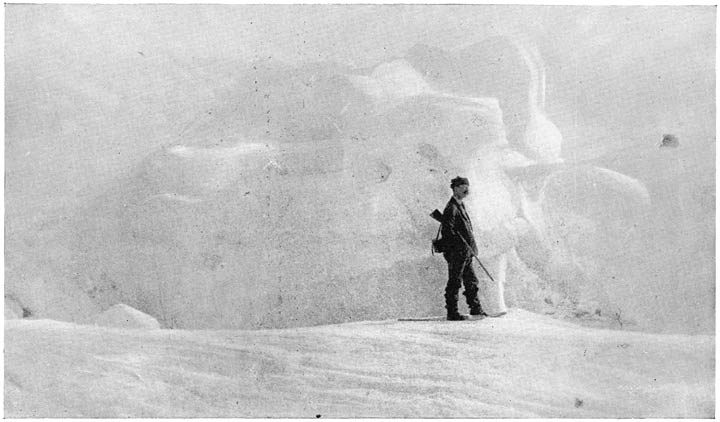

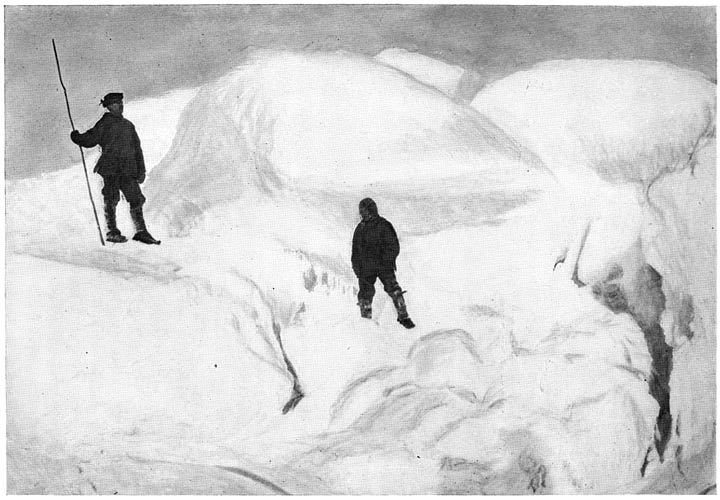

- Pressure-mound near the “Fram” (April, 1895) 621

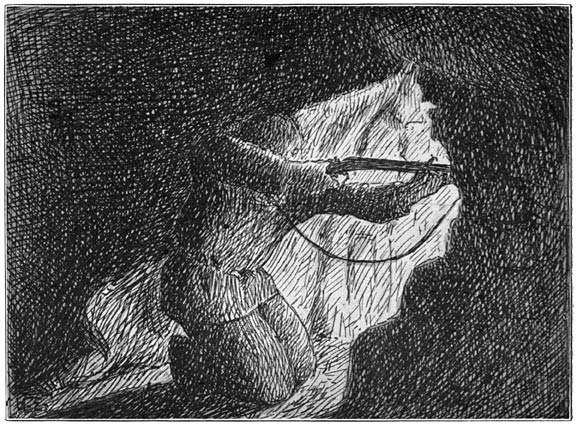

- Ice-smithy (May, 1895) 625

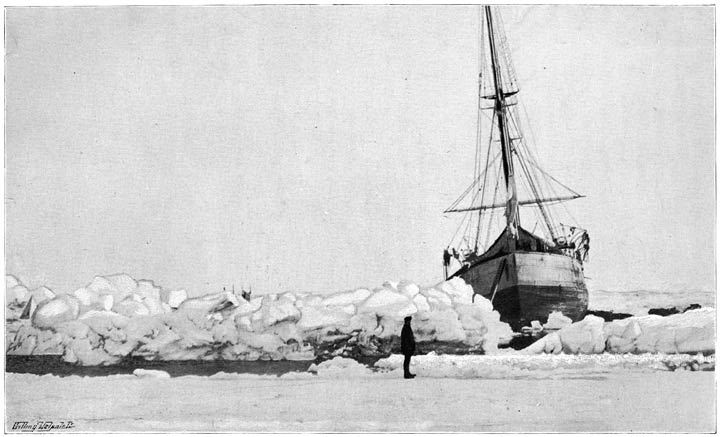

- The “Fram” Before Her Release 627

- The Procession (May 17, 1895) 629

- Tailpiece 632

- Channel Astern of the “Fram” (June, 1895) 635

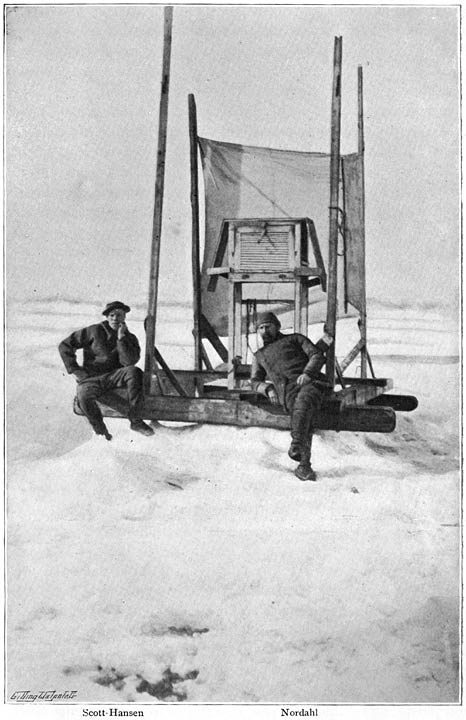

- Movable Meteorological Station on the Ice (July, 1895) 639

- Observation with Sextant and Artificial Horizon (July, 1895) 645

- Cleaning the Accumulators before Stowing Away (July, 1895) 653

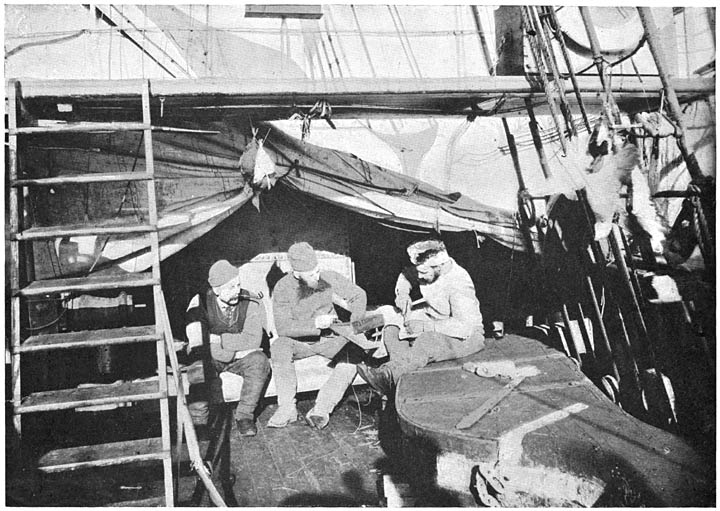

- Workshop on Deck (July, 1895) 659

- Pettersen and Blessing on a Hummock (April, 1895) 673

- Lars Pettersen on Snow-shoes 679

- Tailpiece 682

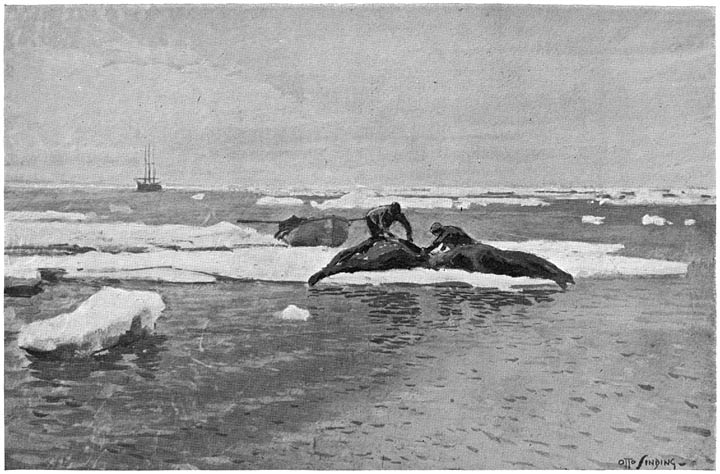

- Flaying Walruses 697

- Tailpiece 706

- The Members of the Expedition after Their Return to Christiania 709

[xi]

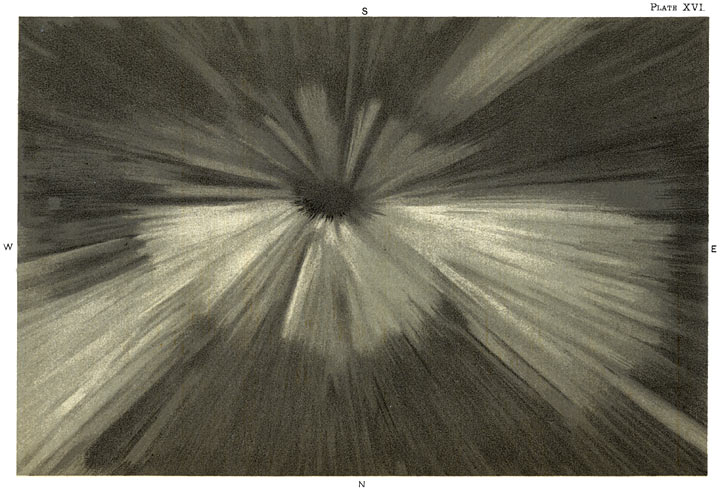

Colored Plates in Vol. II.

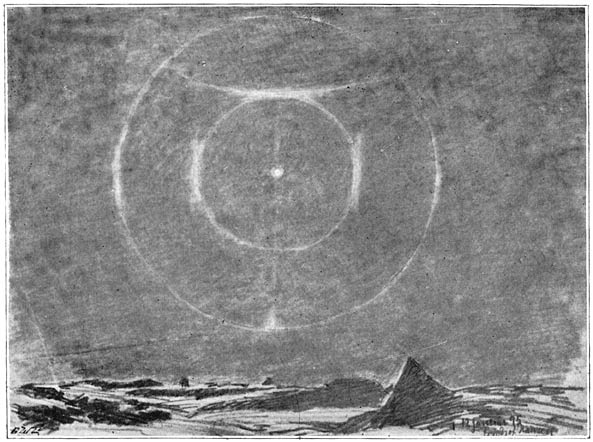

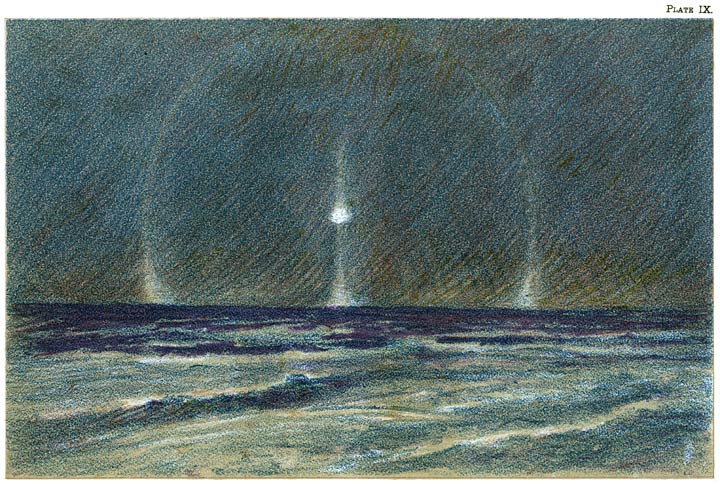

- IX. Light Phenomena in the Polar Night (November 22, 1893) Facing p. 96

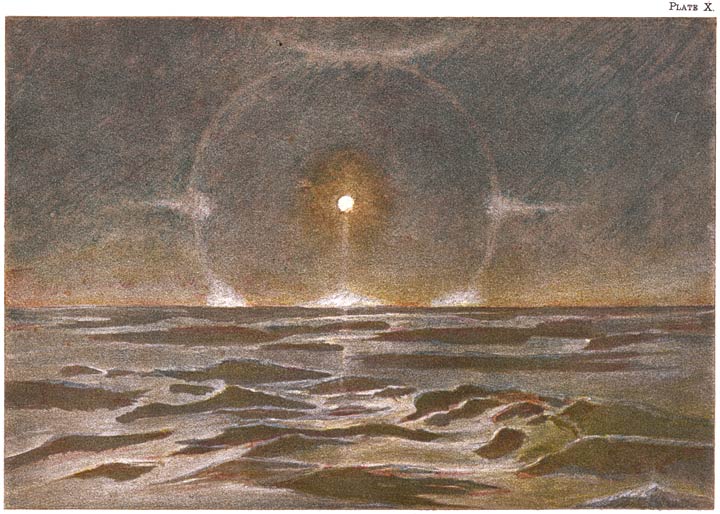

- X. The Polar Night (November 24, 1893) ” 176

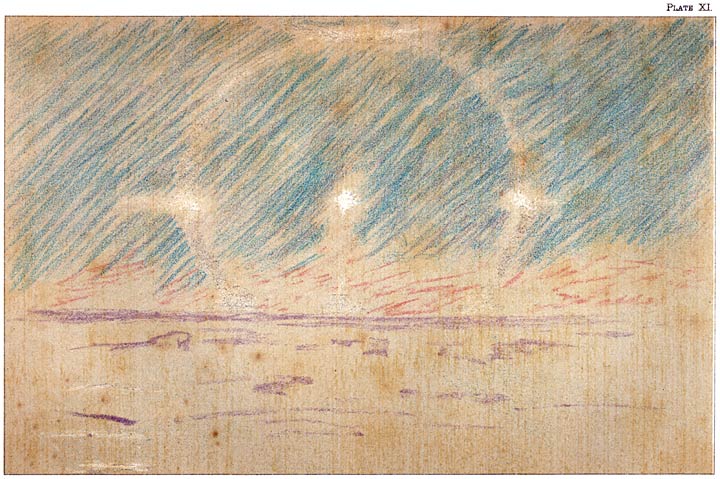

- XI. Moon-ring with Mock Moons, and a Suggestion of Horizontal Axes (November 24, 1893) ” 248

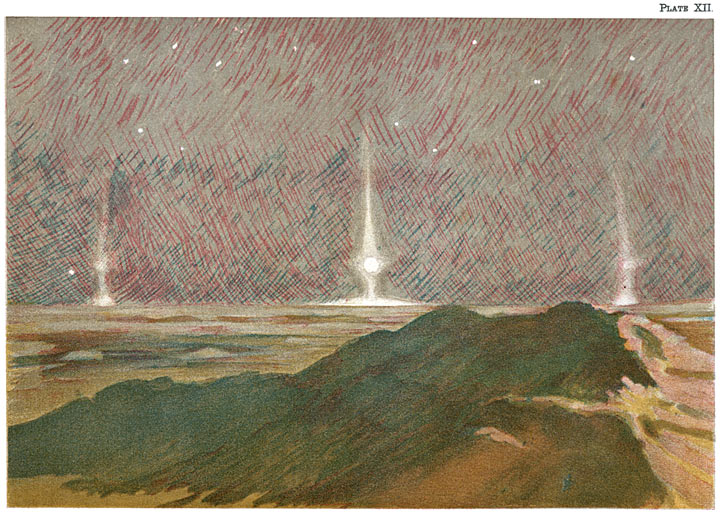

- XII. Moonlight Phenomena at the Beginning of the Polar Night (November, 1893) ” 320

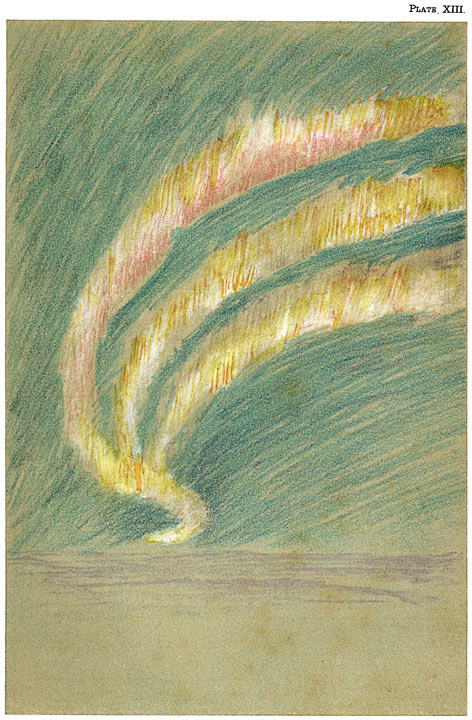

- XIII. Streamers of Aurora Borealis (November 28, 1893) ” 400

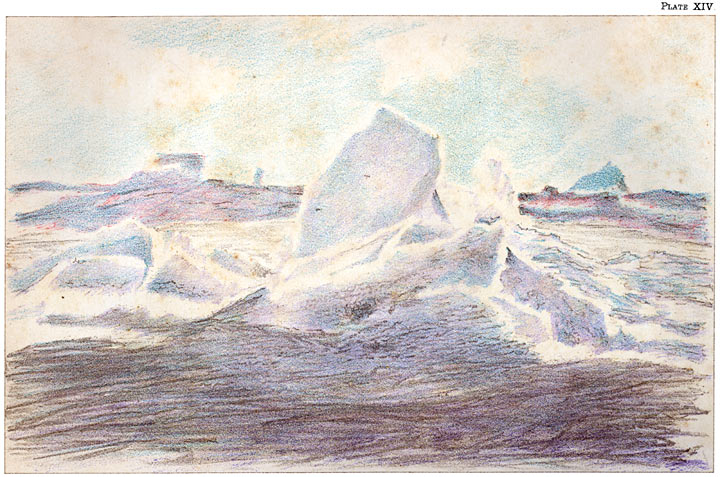

- XIV. Ice near the “Fram” (July 4, 1894) ” 472

- XV. Aurora Borealis (October 18, 1894) ” 584

- XVI. An Auroral Crown (December, 1894) ” 664

[1]

Farthest North

Chapter I

We Prepare for the Sledge Expedition

Who are to be the two members of the expedition? Sverdrup and I have tested each other before at this sort of work, and we could manage very well; but we cannot both leave the Fram: that is perfectly clear without further argument. One of us must remain behind to take on himself the responsibility of bringing the others home in safety; but it is equally clear that one of us two must conduct the sledge expedition, as it is we who have the necessary experience. Sverdrup has a great desire to go; but I cannot think otherwise than that there is more risk in leaving the Fram than in remaining on board her. Consequently if I were to let him go, I should be transferring to him the more dangerous task, while keeping the easier one to myself. If he perished, should I ever be able to forgive myself for letting him go, even if it was at his own desire? He is nine years older than I am; I should certainly feel it [2]to be a very uncomfortable responsibility. And as regards our comrades, which of us would it be most to their interest to keep on board? I think they have confidence in both of us, and I think either of us would be able to take them home in safety, whether with or without the Fram. But the ship is his especial charge, while on me rests the conduct of the whole, and especially of the scientific investigations; so that I ought to undertake the task in which important discoveries are to be made. Those who remain with the ship will be able, as aforesaid, to carry on the observations which are to be made on board. It is my duty therefore, to go, and his to remain behind. He, too, thinks this reasonable.

I have chosen Johansen to be my companion, and he is in all respects well qualified for that work. He is an accomplished snow-shoer, and few can equal his powers of endurance—a fine fellow, physically and mentally. I have not yet asked him, but think of doing so soon, in order that he may be prepared betimes. Blessing and Hansen also would certainly be all eagerness to accompany me; but Hansen must remain behind to take charge of the observations, and Blessing cannot desert his post as doctor. Several of the others, too, would do quite well, and would, I doubt not, be willing enough.

This expedition to the north, then, is provisionally decided on. I shall see what the winter will bring us. Light permitting, I should prefer to start in February.

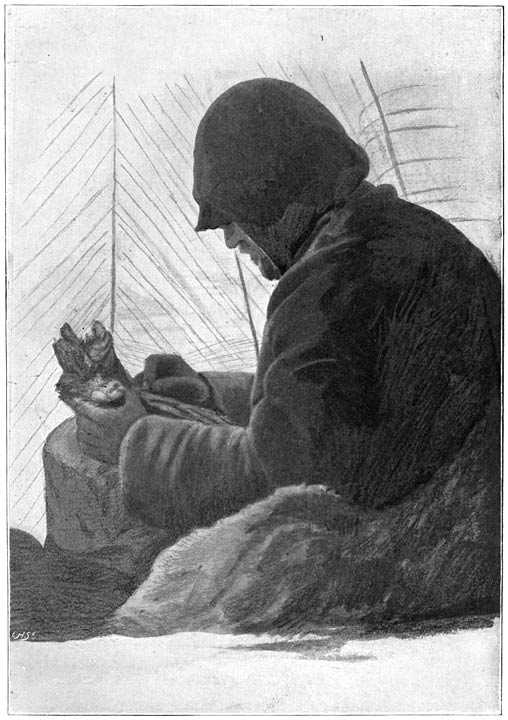

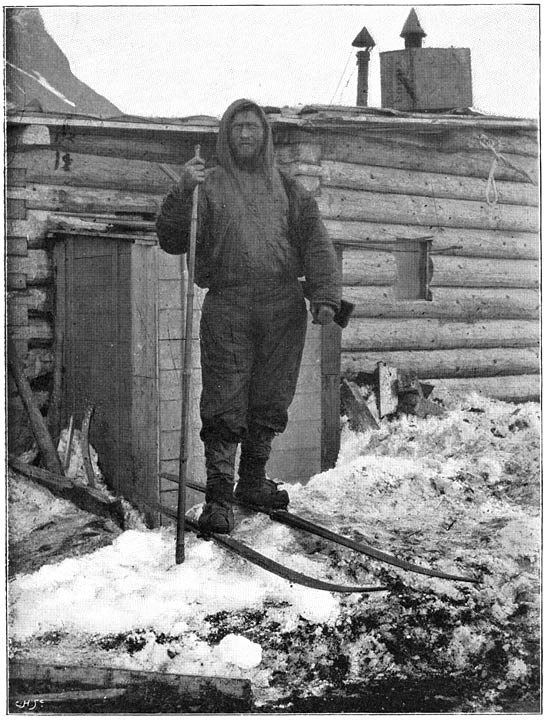

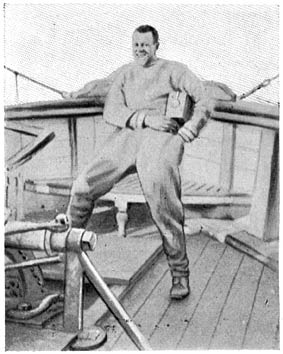

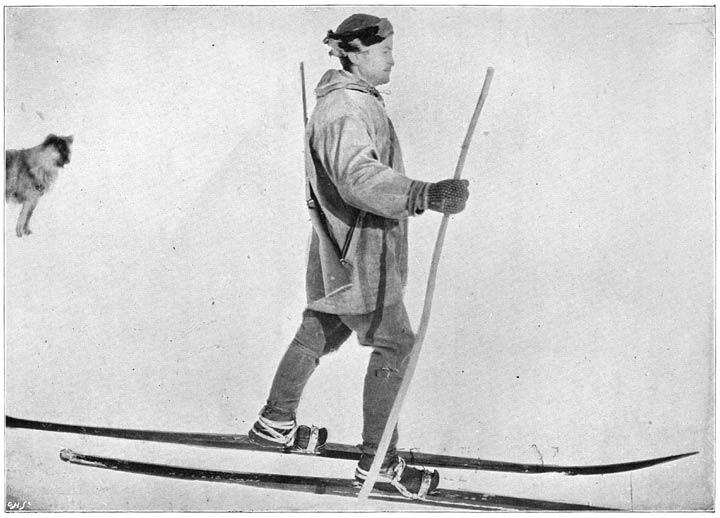

Hjalmar Johansen

(From a photograph taken in December, 1893)

[3]

“Sunday, November 18th. It seems as if I could not properly realize the idea that I am really to set out, and that in three months’ time. Sometimes I delude myself with charming dreams of my return home after toil and victory, and then all is clear and bright. Then these are succeeded by thoughts of the uncertainty and deceptiveness of the future and what may be lurking in it, and my dreams fade away like the northern lights, pale and colorless.

“‘Ihr naht euch wieder, schwankende Gestalten.’

“Ugh! These everlasting cold fits of doubt! Before every decisive resolution the dice of death must be thrown. Is there too much to venture, and too little to gain? There is more to be gained, at all events, than there is here. Then is it not my duty? Besides, there is only one to whom I am responsible, and she...? I shall come back, I know it. I have strength enough for the task. ‘Be thou true unto death, and thou shalt inherit the crown of life.’

“We are oddly constructed machines. At one moment all resolution, at the next all doubt.... To-day our intellect, our science, all our ‘Leben und Treiben,’ seem but a pitiful Philistinism, not worth a pipe of tobacco; to-morrow we throw ourselves heart and soul into these very researches, consumed with a burning thirst, to absorb everything into ourselves, longing to spy out fresh paths, and fretting impatiently at our inability to solve [4]the problem fully and completely. Then down we sink again in disgust at the worthlessness of it all.

“‘As a grain of dust on the balance is the whole world; as a drop of morning dew that falls on the ground.’ If man has two souls, which then is the right one?

“It is nothing new to suffer from the fact that our knowledge can be but fragmentary, that we can never fathom what lies behind. But suppose, now, that we could reckon it out, that the inmost secret of it all lay as clear and plain to us as a rule-of-three sum, should we be any the happier? Possibly just the reverse. Is it not in the struggle to attain knowledge that happiness consists? I am very ignorant, consequently the conditions of happiness are mine.

“Let me fill a soothing pipe and be happy.

“No, the pipe is not a success. Twist tobacco is not delicate enough for airy dreams. Let me get a cigar. Oh, if one had a real Havana!

“H’m! as if dissatisfaction, longing, suffering, were not the very basis of life. Without privation there would be no struggle, and without struggle no life, that is as certain as that two and two make four. And now the struggle is to begin; it is looming yonder in the north. Oh, to drink delight of battle in long, deep draughts! Battle means life, and behind it victory beckons us on.

“I close my eyes. I hear a voice singing to me: [5]

“‘In amongst the fragrant birch,

In amongst the flowers’ perfume,

Deep into the pine-wood’s church.’

“Monday, November 19th. Confounded affectation all this Weltschmerz; you have no right to be anything but a happy man. And if you feel out of spirits, it ought to cheer you up simply to go on deck and look at these seven puppies that come frisking and springing about you, and are ready to tear you to pieces in sheer enjoyment of life. Life is sunshine to them, though the sun has long since gone, and they live on deck beneath a tent, so that they cannot even see the stars. There is ‘Kvik,’ the mother of the family, among them, looking so plump and contented as she wags her tail. Have you not as much reason to be happy as they? Yet they too have their misfortunes. The afternoon of the day before yesterday, as I was sitting at work, I heard the mill going round and round, and Peter taking food to the puppies, which, as usual, had a bit of a fight over the meat-pan; and it struck me that the axle of the mill whirling unguarded on the deck was an extremely dangerous affair for them. Ten minutes later I heard a dog howling, a more long-drawn, uncomfortable kind of howl than was usual when they were fighting, and at the same moment the mill slowed down. I rushed out. There I saw a puppy right in the axle, whirling round with it and howling piteously, so that it cut one to the soul. Bentzen was hanging on to the brake-rope, hauling at it with all his [6]might and main; but still the mill went round. My first idea was to seize an axe that was lying there to put the dog out of its misery, its cries were so heartrending; but on second thoughts I hurried on to help Bentzen, and we got the mill stopped. At the same moment Mogstad also came up, and while we held the mill he managed to set the puppy free. Apparently there was still some life in it, and he set to work to rub it gently and coax it. The hair of its coat had somehow or other got frozen on to the smooth steel axle, and the poor beast had been swung round and bumped on the deck at every revolution of the wheel. At last it actually raised its head, and looked round in a dazed way. It had made a good many revolutions, so that it is no wonder if it found some difficulty in getting its bearings at first. Then it raised itself on its fore-paws, and I took it aft to the half-deck and stroked and patted it. Soon it got on all four legs again, and began shambling about, without knowing where it was going.

“‘It is a good thing it was caught by the hair,’ said Bentzen, ‘I thought it was hanging fast by its tongue, as the other one did.’ Only think of being fixed by the tongue to a revolving axle—the mere notion makes one shudder! I took the poor thing down into the saloon and did all I could for it. It soon got all right again, and began playing with its companions as before. A strange life to rummage about on deck in the dark and cold; but whenever one goes up with a lantern they [7]come tearing round, stare at the light, and begin bounding and dancing and gambolling with each other round it, like children round a Christmas-tree. This goes on day after day, and they have never seen anything else than this deck with a tarpaulin over it, not even the clear blue sky; and we men have never seen anything else than this earth!

“The last step over the bridge of resolution has now been taken. In the forenoon I explained the whole matter to Johansen in pretty much the same terms as I have used above; and then I expatiated on the difficulties that might occur, and laid strong emphasis on the dangers one must be prepared to encounter. It was a serious matter—a matter of life or death—this one must not conceal from one’s self. He must think the thing well over before determining whether he would accompany me or not. If he was willing to come I should be glad to have him with me; but I would rather, I said, he should take a day or two to think it well over before he gave me his answer. He did not need any time for reflection, he said; he was quite willing to go. Sverdrup had long ago mentioned the possibility of such an expedition, and he had thought it well over, and made up his mind that if my choice should fall on him he would take it as a great favor to be permitted to accompany me. ‘I don’t know whether you’ll be satisfied with this answer, or whether you would like me still to think it over; but I should certainly never change my mind.’ ‘No, if [8]you have already thought it seriously over—thought what risks you expose yourself to—the chance, for instance, that neither of us may ever see the face of man again—and if you have reflected that even if we get through safe and sound you must necessarily face a great deal of hardship on an expedition like this—if you have made up your mind to all this I don’t insist on your reflecting any longer about it.’ ‘Yes, that I have.’ ‘Well, then, that is settled. To-morrow we shall begin our preparations for the trip. Hansen must see about appointing another meteorological assistant.’

“Tuesday, November 20th. This evening I delivered an address to the whole ship’s company, in which I announced the determination that had been arrived at, and explained to them the projected expedition. First of all, I briefly went through the whole theory of our undertaking, and its history from the beginning, laying stress on the idea on which my plans had been built up—namely, that a vessel which got frozen in north of Siberia must drift across the Polar Sea and out into the Atlantic, and must pass somewhere or other north of Franz Josef Land and between it and the Pole. The object of the expedition was to accomplish this drift across the unknown sea, and to pursue investigations there. I pointed out to them that these investigations would be of equal importance whether the expedition actually passed across the Pole itself or at some distance from it. Judging from our experiences hitherto, we could not entertain [11]any doubt that the expedition would solve the problem it had set before it; everything had up to the present gone according to our anticipations, and it was to be hoped and expected that this would continue to be the case for the remainder of the voyage. We had, therefore, every prospect of accomplishing the principal part of our task; but then the question arose whether more could not be accomplished, and thereupon I proceeded to explain, in much the same terms as I have used above, how this might be effected by an expedition northward.

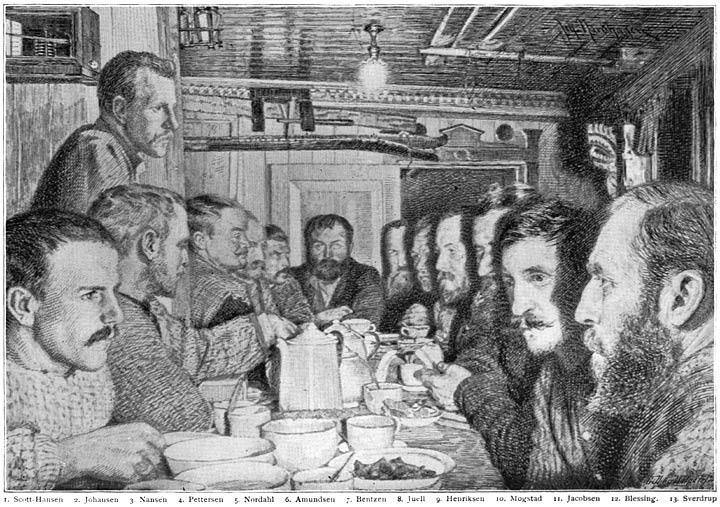

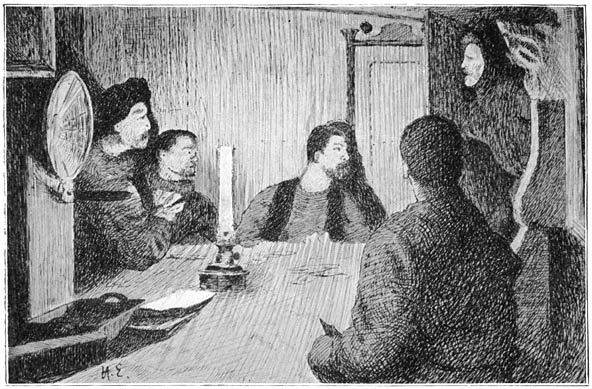

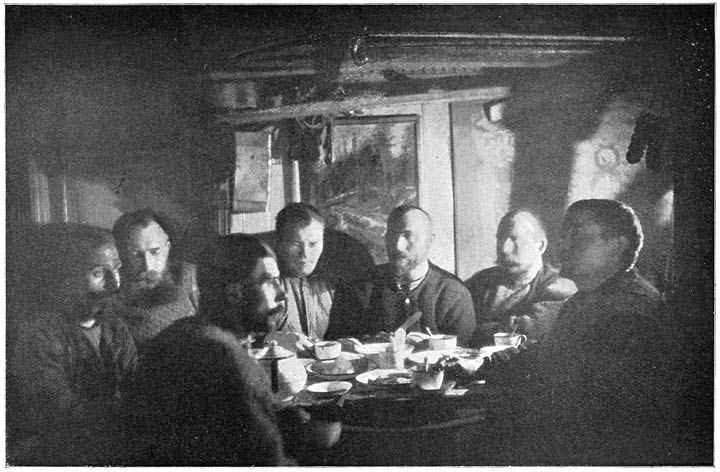

At the Supper-table, February 14, 1895.

1. Scott-Hansen 2. Johansen 3. Nansen 4. Pettersen 5. Nordahl 6. Amundsen 7. Bentzen 8. Juell 9. Henriksen 10. Mogstad 11. Jacobsen 12. Blessing 13. Sverdrup

(By Johan Nordhagen, from a photograph)

“I had the impression that every one was deeply interested in the projected expedition, and that they all thought it most desirable that it should be attempted. The greatest objection, I think, they would have urged against it, had they been asked, would have been that they themselves could not take part in it. I impressed on them, however, that while it was unquestionably a fine thing to push on as far as possible towards the north, it was no whit less honorable an undertaking to bring the Fram safe and sound right through the Polar Sea, and out on the other side; or if not the Fram, at all events themselves without any loss of life. This done, we might say, without fear of contradiction, that it was well done. I think they all saw the force of this, and were satisfied. So now the die is cast, and I must believe that this expedition will really take place.”

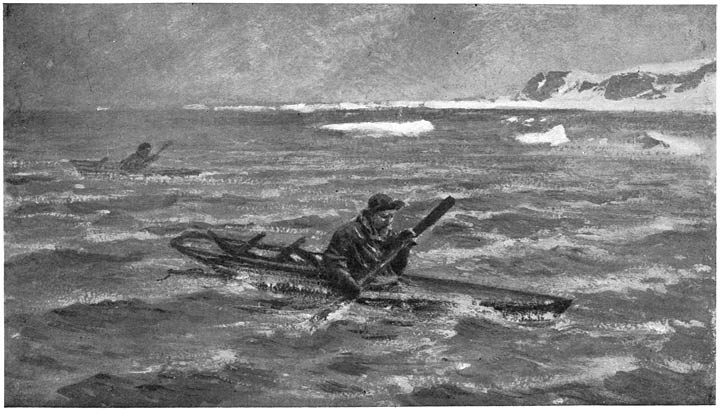

So we set about our preparations for it in downright [12]earnest. I have already mentioned that at the end of the summer I had begun to make a kayak for a single man, the frame of which was of bamboo carefully lashed together. It was rather slow work, and took several weeks, but it turned out both light and strong. When completed the framework weighed 16 pounds. It was afterwards covered with sail-cloth by Sverdrup and Blessing, when the whole boat weighed 30 pounds. After finishing this I had intrusted Mogstad with the task of building a similar one. Johansen and I now set to work to make a cover for it. These kayaks were 3.70 metres (12 feet) long, about O.7 metre (28 inches) wide in the middle, and one was 30 centims. (12 inches) and the other 38 centims. (15 inches) deep. This is considerably shorter and wider than an ordinary Eskimo kayak, and consequently these boats were not so light to propel through the water. But as they were chiefly intended for crossing over channels and open spaces in the ice, and coasting along possible land, speed was not of much importance. The great thing was that the boats should be strong and light, and should be able to carry, in addition to ourselves, provisions and equipments for a considerable time. If we had made them longer and narrower, besides being heavier they would have been more exposed to injury in the course of transport over the uneven ice. As they were built they proved admirably adapted for our purpose. When we loaded them with care we could stow away in them provisions and equipment for three months at least [13]for ourselves, besides a good deal of food for the dogs; and we could, moreover, carry a dog or two on the deck. In other respects they were essentially like the Eskimo kayaks, full decked, save for an aperture in the middle for a man to sit in. This aperture was encircled by a wooden ring, after the Eskimo fashion, over which we could slip the lower part of our sealskin jackets, specially adjusted for this purpose, so that the junction between boat and jacket was water-tight. When these jackets were drawn tight round the wrists and face the sea might sweep right over us without a drop of water coming into the kayak. We had to provide ourselves with such boats in case of having to cross open stretches of sea on our way to Spitzbergen, or, if we chose the other route, between Franz Josef Land and Novaya Zemlya. Besides this aperture in the middle, there were small trap-doors fore and aft in the deck, to enable us to put our hands in and stow the provisions, and also get things out more readily, without having to take out all the freight through the middle aperture, in case what we wanted lay at either extremity. These trap-doors, however, could be closed so as to be quite water-tight. To make the canvas quite impervious to water, the best plan would have been to have sized it, and then painted it externally with ordinary oil paint; but, on the one hand, it was very difficult to do this work in the extreme cold (in the hold the temperature was -20° C., -4° Fahr.), and, on the other hand, I was afraid the paint might render the canvas [14]too hard and brittle, and apt to have holes knocked in it during transport over the ice. Therefore I preferred to steep it in a mixture of paraffin and tallow, which added somewhat to the weight of the kayaks, so that altogether they came to weigh about 36 pounds apiece.

I had, moreover, some hand-sledges made especially for this expedition; they were supple and strong, designed to withstand the severe tests to which an expedition with dogs and heavy freights over the uneven drift-ice would necessarily expose them. Two of these sledges were about the same length as the kayaks—that is, 12 feet. I also made several experiments with respect to the clothes we should wear, and was especially anxious to ascertain whether it would do to go in our thick wolfskin garments, but always came to the conclusion that they were too warm. Thus, on November 29th I write: “Took another walk northward in my wolfskin dress; but it is still too mild (-37.6° C.). I sweated like a horse, though I went fasting and quite gently. It is rather heavy going now in the dark when one cannot use snowshoes. I wonder when it will be cold enough to use this dress.”

On December 9th again we went out on snow-shoes. “It was -41° C. (-41.8° Fahr.). Went in wolfskin dress, but the perspiration poured down our backs enough to turn a mill. Too warm yet; goodness knows if it ever will be cold enough.”

Of course, we made some experiments with the tent [15]and with the cooking apparatus. On December 7th I write: “I pitched the silk tent we are going to take, and used our cooking apparatus in it. From repeated trials it appeared that from ice of -35° C. (-31° Fahr.), we boiled 3 litres of water (5¼ pints), and at the same time melted 5 litres (8¾ pints) in an hour and a half, with a consumption of about 120 grammes of snowflake petroleum. Next day we boiled 2½ litres of water (over 4 pints), and melted 2½ litres in one hour with 100 grammes of snowflake petroleum. Yesterday we made about two litres of excellent oatmeal porridge, and at the same time got some half-melted ice and a little water in little over half an hour, with 50 grammes of snowflake petroleum. Thus there will be no very great consumption of fuel in the day.”

Then I made all kinds of calculations and computations in order to find out what would be the most advantageous kind of provisions for our expedition, where it was of the greatest moment that the food both for dogs and men should be nutritious, and yet should not weigh more than was absolutely necessary. Later on, in the list of our equipments, I shall give the final result of my deliberations on this matter. Besides all this, we had, of course, to consider and test the instruments to be taken with us, and to go into many other matters, which, though perhaps trifles in themselves, were yet absolutely necessary. It is on the felicitous combination of all these trifles that ultimate success depends.

We two passed the greater portion of our time in [16]these preparations, which also kept many of the others pretty busy during the winter. Mogstad, for instance, found steady employment in making sledges and fitting them with runners, etc. Sverdrup busied himself in making sleeping-bags and many other things. Juell was appointed dog-tailor, and when he was not busy in the galley, his time was devoted to taking the measurements of the dogs, making harness for them and testing it. Blessing, too, fitted up for us a small, light medicine-chest, containing selected drugs, bandages, and such other things as might be of use. One man was constantly employed in copying out all our journals and scientific observations, etc., etc., on thin paper in a contracted form, as I wanted, by way of doubly assuring their preservation, to take a copy of them along with me. Hansen was occupied in preparing tabular forms necessary for our observations, curves of the movement of our chronometers, and other such things. Besides this, he was to make a complete chart of our voyage and drifting up to the present time.

Scott-Hansen’s Observatory

I could not, however, lay too great a claim on his valuable time, as it was necessary that he should continue his scientific observations without interruption. During this autumn he had greatly increased the comfort of his work by building, along with Johansen, an observation-hut of snow, not unlike an Eskimo cabin. He found himself very much at his ease in it, with a petroleum lamp hanging from the roof, the light of which, being reflected by the white snow walls, made quite a [19]brilliant show. Here he could manipulate his instruments quietly and comfortably, undisturbed by the biting wind outside. He thought it quite warm there, too, when he could get the temperature up to something like 20° below freezing-point, so that he was able without much inconvenience to adjust his instruments with bare hands. Here he worked away indefatigably at his observations day after day, watching the often mysterious movements of the magnetic needle, which would sometimes give him no end of trouble. One day—it was November 24th—he came into supper a little after 6 o’clock quite alarmed and said, “There has just been a singular inclination of the needle to 24°, and, remarkably enough, its northern extremity pointed to the east. I cannot remember ever having heard of such an inclination.” He also had several others of about 15°. At the same time, through the opening into his observatory he noticed that it was unusually light out-of-doors, and that not only the ship, but the ice in the distance, was as plainly visible as if it had been full moonlight. No aurora, however, could be discerned through the thick clouds that covered the sky. It would appear, then, that this unusual inclination was in some way connected with the northern lights, though it was to the east and not to the west, as usual. There could be no question of any disturbance of the floe on which we were lying; for everything had been perfectly still and quiet, and it is inconceivable that a disturbance which could cause such a remarkable oscillation [20]of two points and back again in so short a space of time should not have been noticed and heard on board. This theory, therefore, is entirely excluded, and the whole matter seems to me, for the present, to be incomprehensible. Blessing and I at once went on deck to look at the sky. Certainly it was so light that we could see the lanes in the ice astern quite plainly; but there was nothing remarkable in that, it happened often enough.

“Friday, November 30th. I found a bear’s track on the ice in front of our bow. The bear had come from the east, trotting very gently along the lane, on the newly frozen ice, but he must have been scared by something or other ahead of the vessel, as he had gone off again with long strides in the same direction in which he had come. Strange that living creatures should be roaming about in this desert. What can they have to do here? If only one had such a stomach one could at least stand a journey to the Pole and back without a meal. We shall probably have him back again soon—that is, if I understand his nature aright—and then perhaps he will come a little closer, so that we may have a good look at him.1

“I paced the lane in front of the port bow. It was 348 paces across, and maintained the same width for a considerable distance eastward; nor can it be much [21]narrower for a great distance to the west. Now, when one bears in mind that the lane behind us is also of considerable width, it is rather consoling, after all, to think that the ice does permit of such large openings. There must be room enough to drift, if we only get wind—wind which will never come. On the whole, November has been an uncommonly wretched month. Driven back instead of forward—and yet this month was so good last year. But one can never rely on the seasons in this dreadful sea; taking all in all, perhaps, the winter will not be a bit better than the summer. Yet, it surely must improve—I cannot believe otherwise.

“The skies are clouded with a thick veil, through which the stars barely glisten. It is darker than usual, and in this eternal night we drift about, lonely and forsaken, ‘for the whole world was filled with a shining light and undisturbed activity. Above those men alone brooded nought but depressing night—an image of that gloom which was soon to swallow them up.’

“This dark, deep, silent void is like the mysterious, unfathomable well into which you look for that something which you think must be there, only to meet the reflection of your own eyes. Ugh! the worn-out thoughts you can never get rid of become in the end very wearisome company. Is there no means of fleeing from one’s self, to grasp one single thought—only a single one, which lies outside one’s self—is there no way except death? But death is certain; one day it will come, silent and [22]majestic; it will open Nirvana’s mighty portal, and we shall be swept away into the sea of eternity.

“Sunday, December 2d. Sverdrup has now been ill for some days; during the last day or two he has been laid up in his berth, and is still there. I trust it is nothing serious; he himself thinks nothing of it, nevertheless it is very disquieting. Poor fellow, he lives entirely on oatmeal gruel. It is an intestinal catarrh, which he probably contracted through catching cold on the ice. I am afraid he has been rather careless in this respect. However, he is now improving, so that probably it will soon pass off; but it is a warning not to be over-confident. I went for a long walk this morning along the lane; it is quite a large one, extending a good way to the east, and being of considerable breadth at some points. It is only after walking for a while on the newly frozen ice, where walking is as easy and comfortable as on a well-trodden path, and then coming up to the snow-covered surface of the old ice again, that one thoroughly appreciates for the first time what it means to go without snow-shoes; the difference is something marvellous. Even if I have not felt warm before, I break out into a perspiration after going a short distance over the rough ice. But what can one do? One cannot use snow-shoes; it is so dark that it is difficult enough to grope one’s way about with ordinary boots, and even then one stumbles about or slips down between great blocks of ice.

“I am now reading the various English stories of [23]the polar expeditions during the Franklin period, and the search for him, and I must admit I am filled with admiration for these men and the amount of labor they expended. The English nation, truly, has cause to be proud of them. I remember reading these stories as a lad, and all my boyish fancies were strangely thrilled with longing for the scenery and the scenes which were displayed before me. I am reading them now as a man, after having had a little experience myself; and now, when my mind is uninfluenced by romance, I bow in admiration. There was grit in men like Parry, Franklin, James Ross, Richardson, and last, but not least, in M’Clintock, and, indeed, in all the rest. How well was their equipment thought out and arranged, with the means they had at their disposal! Truly, there is nothing new under the sun. Most of what I prided myself upon, and what I thought to be new, I find they had anticipated. M’Clintock used the same thing forty years ago. It was not their fault that they were born in a country where the use of snow-shoes is unknown, and where snow is scarcely to be found throughout the whole winter. Nevertheless, despite the fact that they had to gain their experience of snow and snow travel during their sojourn up here; despite the fact that they were without snow-shoes and had to toil on as best they could with sledges with narrow runners over uneven snow-covered drift-ice—what distances did they not cover, what fatigues and trials did they not endure! No [24]one has surpassed and scarcely any one approached them, unless, perhaps, the Russians on the Siberian coast; but then they have the great advantage of being natives of a country where snow is not uncommon.

“Friday, December 14th. Yesterday we held a great festivity in honor of the Fram as being the vessel which has attained the highest latitude (the day before yesterday we reached 82° 30′ north latitude).

“The bill of fare at dinner was boiled mackerel, with parsely-butter sauce; pork cutlets and French pease; Norwegian wild strawberries, with rice and milk; Crown malt extract; afterwards coffee. For supper: new bread and currant cake, etc., etc. Later in the evening, a grand concert. Sweets and preserved pears were handed round. The culminating point of the entertainment was reached when a steaming hot and fragrant bowl of cherry-punch was carried in and served round amidst general hilarity. Our spirits were already very high, but this gave color to the whole proceedings. The greatest puzzle to most of them was where the ingredients for the punch, and more particularly the alcohol, had come from.2

“Then followed the toasts. First, a long and festive one to ‘The Fram,’ which had now shown what she was capable of. It ran somewhat to this effect: ‘There were many wise men who shook their heads when we started, and sent us ominous farewell greetings. But their head-shakings [25]would have been less vigorous and their evil forebodings milder if they could have seen us at this moment, drifting quietly and at our ease across the most northerly latitudes ever attained by any vessel, and still farther northward. And the Fram is now not only the most northerly vessel on the globe, but has already passed over a large expanse of hitherto unknown regions, many degrees farther north than have ever been reached in this ocean on this side of the Pole. But we hope she will not stop here; concealed behind the mist of the future there are many triumphs in store for us—triumphs which will dawn upon us one by one when their time has come. But we will not speak of this now; we will be content with what has hitherto been achieved, and I believe that the promise implied in Björnson’s greeting to us and to the Fram, when she was launched, has already been fulfilled, and with him we can exclaim:

“‘“Hurrah for the ship and her voyage dread!

Where never before a keel has sped,

Where never before a name was spoken,

By Norway’s name is the silence broken.’”

“‘We could not help a peculiar feeling, almost akin to shame, when comparing the toil and privation, and frequently incredible sufferings, undergone by our predecessors in earlier expeditions with the easy manner in which we are drifting across unknown expanses of our globe larger than it has been the lot of most, if not all, of the former polar explorers to travel over at a stretch. [26]Yes, truly, I think we have every reason to be satisfied with our voyage so far and with the Fram, and I trust we shall be able to bring something back to Norway in return for the trust, the sympathy, and the money which she has expended on us. But let us not on this account forget our predecessors; let us admire them for the way in which they struggled and endured; let us remember that it is only through their labors and achievements that the way has been prepared for the present voyage. It is owing to their collective experience that man has now got so far as to be able to cope to some extent with what has hitherto been his most dangerous and obstinate enemy in the Arctic regions—viz., the drift-ice—and to do so by the very simple expedient of going with it and not against it, and allowing one’s self to be hemmed in by it, not involuntarily, but intentionally, and preparing for it beforehand. On board this vessel we try to cull the fruits of all our predecessors’ experiences. It has taken years to collect them; but I felt that with these I should be enabled to face any vicissitude of fate in unknown waters. I think we have been fortunate. I think we are all of the opinion that there is no imaginable difficulty or obstacle before us that we ought not to be able to overcome with the means and resources we possess on board, and be thus enabled to return at last to Norway safe and sound, with a rich harvest. Therefore let us drink a bumper to the Fram!’

“Next there followed some musical items and a performance [27]by Lars, the smith, who danced a pas seul, to the great amusement of the company. Lars assured us that if he ever reached home again and were present at a gathering similar to those held at Christiania and Bergen on our departure, his legs should be taxed to their uttermost. This was followed by a toast to those at home who were waiting for us year after year, not knowing where to picture us in thought, who were vainly yearning for tidings of us, but whose faith in us and our voyage was still firm—to those who consented to our departure, and who may well be said to have made the greatest sacrifice.

“The festivity continued with music and merriment throughout the evening, and our good humor was certainly not spoiled when our excellent doctor came forward with cigars—a commodity which is getting highly valued up here, as, unfortunately it is becoming very scarce. The only cloud in our existence is that Sverdrup has not yet quite recovered from his catarrh. He must keep strict diet, and this does not at all suit him, poor fellow! He is only allowed wheaten bread, milk, raw bear’s flesh, and oatmeal porridge; whereas if he had his own way he would eat everything, including cake, preserves, and fruit. But he has returned to duty now, and has already been out for a turn on the ice.

“It was late at night when I retired to my cabin, but I was not yet in a fit mood to go to sleep. I felt I must go out and saunter in the wonderful moonlight. Around the moon there was, as usual, a large ring, and above it [28]there was an arc, which just touched it at the upper edge, but the two ends of which curved downward instead of upward. It looked as if it were part of a circle whose centre was situated far below the moon. At the lower edge of the ring there was a large mock moon, or, rather, a large luminous patch, which was most pronounced at the upper part, where it touched the ring, and had a yellow upper edge, from which it spread downward in the form of a triangle. It looked as if it might be an arc of a circle on the lower side of, and in contact with, the ring. Right across the moon there were drifting several luminous cirrus streaks. The whole produced a fantastic effect.

“Saturday, December 22d. The same southeasterly wind has turned into a regular storm, howling and rattling cheerily through the rigging, and we are doubtless drifting northward at a good rate. If I go outside the tent on deck, the wind whistles round my ears, and the snow beats into my face, and I am soon covered with it. From the snow-hut observatory, or even at a lesser distance, the Fram is invisible, and it is almost impossible to keep one’s eyes open, owing to the blinding snow. I wonder whether we have not passed 83°? But I am afraid this joy will not be a lasting one; the barometer has fallen alarmingly, and the wind has generally been up to 13 or 14 metres (44 or 50 feet) per second. About half-past twelve last night the vessel suddenly received a strong pressure, rattling everything on board. I could [29]feel the vibration under me for a long time afterwards while lying in my berth. Finally, I could hear the roaring and grating caused by the ice-pressure. I told the watch to listen carefully, and ascertain where the pressure was, and to notice whether the floe on which we were lying was likely to crack, and whether any part of our equipment was in danger. He thought he could hear the noise of ice-pressure both forward and aft, but it was not easy to distinguish it from the roar of the tempest in the rigging. To-day about 12.30 P.M. the Fram received another violent shock, even stronger than that we had experienced during the night. There was another shake a little later; I suppose there has been a pressure aft, but could hear nothing for the storm. It is odd about this pressure: one would think that the wind was the primary cause; but it recurs pretty regularly, notwithstanding the fact that the spring-tide has not yet set in; indeed, when it commenced a few days ago it was almost a neap-tide. In addition to the pressure of yesterday and last night, we had pressure on Thursday morning at half-past nine and again at half-past eleven. It was so strong that Peter, who was at the sounding-hole, jumped up repeatedly, thinking that the ice would burst underneath him. It is very singular, we have been quiet for so long now that we feel almost nervous when the Fram receives those shocks; everything seems to tremble as if in a violent earthquake.

“Sunday, December 23d. Wind still unchanged, and [30]blowing equally fresh, up to 13 or 14 metres (44 or 47 feet). The snow is drifting and sweeping so that nothing can be distinguished; the darkness is intense. Abaft on the deck there are deep mounds of snow lying round the wheel and the rails, so that when we go up on deck we get a genuine sample of an Arctic winter. The outlook is enough to make you shudder, and feel grateful that instead of having to turn out in such weather, you may dive back again into the tent, and down the companionway into your warm bunk; but soon, no doubt, Johansen and I will have to face it out, day and night, even in such weather as this, whether we like it or not. This morning Pettersen, who has had charge of the dogs this week, came down to the saloon and asked whether some one would come out with him on the ice with a rifle, as he was sure there was a bear. Peter and I went, but we could not find anything. The dogs left off barking when we arrived on the scene, and commenced to play with each other. But Pettersen was right in saying that it was ‘horrid weather,’ it was almost enough to take away one’s breath to face the wind, and the drifting snow forced its way into the mouth and nostrils. The vessel could not be distinguished beyond a few paces, so that it was not advisable to go any distance away from her, and it was very difficult to walk; for, what with snow-drifts and ice-mounds, at one moment you stumbled against the frozen edge of a snow-drift, at another you tumbled into a hole. It was pitch-dark all round. The barometer [31]had been falling steadily and rapidly, but at last it has commenced to rise slightly. It now registers about 726 mm. (28.6 inches). The thermometer, as usual, is describing the inverse curve. In the afternoon it rose steadily until it registered -21.3°C. Now it appears to be falling again a little, but the wind still keeps exactly in the same quarter. It has surely shifted us by now a good way to the north, well beyond the 83d degree. It is quite pleasant to hear the wind whistling and rattling in the rigging overhead. Alas! we know that all terrestrial bliss is short-lived.

“About midnight the mate, who has the watch, comes down and reports that the ice has cracked just beyond the thermometer house, between it and the sounding-hole. This is the same crack that we had in the summer, and it has now burst open again, and probably the whole floe in which we are lying is split from the lane ahead to the lane astern of us. The thermograph and other instruments are being brought on board, so that we may run no risk of losing them in the event of pressure of ice. But otherwise there is scarcely anything that could be endangered. The sounding apparatus is at some distance from the open channel, on the other side. The only thing left there is the shears with the iron block standing over the hole.

“Thursday, December 27th. Christmas has come round again, and we are still so far from home. How dismal it all is! Nevertheless, I am not melancholy. I [32]might rather say I am glad; I feel as if awaiting something great which lies hidden in the future; after long hours of uncertainty I can now discern the end of this dark night; I have no doubt all will turn out successfully, that the voyage is not in vain and the time not wasted, and that our hopes will be realized. An explorer’s lot is, perhaps, hard and his life full of disappointments, as they all say; but it is also full of beautiful moments—moments when he beholds the triumphs of human faith and human will, when he catches sight of the haven of success and peace.

“I am in a singular frame of mind just now, in a state of sheer unrest. I have not felt inclined for writing during the last few days; thoughts come and go, and carry me irresistibly ahead. I can scarcely make myself out, but who can fathom the depths of the human mind. The brain is a puzzling piece of mechanism: ‘We are such stuff as dreams are made of.’ Is it so? I almost believe it—a microcosm of eternity’s infinite ‘stuff that dreams are made of.’

“This is the second Christmas spent far away in the solitude of night, in the realm of death, farther north and deeper into the midst of it than any one has been before. There is something strange in the feeling; and then this, too, is our last Christmas on board the Fram. It makes one almost sad to think of it. The vessel is like a second home, and has become dear to us. Perhaps our comrades may spend another Christmas here, [33]possibly several, without us who will go forth from them into the midst of the solitude. This Christmas passed off quietly and pleasantly, and every one seems to be well content. By no means the least circumstance that added to our enjoyment was that the wind brought us the 83d degree as a Christmas-box. Our luck was, this time, more lasting than I had anticipated; the wind continued fresh on Monday and Tuesday, but little by little it lulled down and veered round to the north and northeast. Yesterday and to-day it has been in the northwest. Well, we must put up with it; one cannot help having a little contrary wind at times, and probably it will not last long.

“Christmas-eve was, of course, celebrated with great feasting. The table presented a truly imposing array of Christmas confectionery: ‘Poor man’s’ pastry, ‘Staghorn’ pastry, honey-cakes, macaroons, ‘Sister’ cake, and what not, besides sweets and the like; many may have fared worse. Moreover, Blessing and I had worked during the day in the sweat of our brow and produced a ‘Polar Champagne 83d Degree,’ which made a sensation, and which we two, at least, believed we had every reason to be proud of, being a product derived from the noble grape of the polar regions—viz., the cloudberry (multer). The others seemed to enjoy it too, and, of course, many toasts were drunk in this noble beverage. Quantities of illustrated books were then brought forth; there was music, and stories, and songs, and general merriment. [34]

“On Christmas day, of course, we had a special dinner. After dinner coffee and curaçao made here on board, and Nordahl then came forward with Russian cigarettes. At night a bowl of cloudberry punch was served out, which did not seem by any means unwelcome. Mogstad played the violin, and Pettersen was electrified thereby to such a degree that he sang and danced to us. He really exhibits considerable talent as a comedian, and has a decided bent towards the ballet. It is astonishing what versatility he displays: engineer, blacksmith, tinsmith, cook, master of ceremonies, comedian, dancer, and, last of all, he has come out in the capacity of a first-class barber and hair-dresser. There was a grand ‘ball’ at night; Mogstad had to play till the perspiration poured from him; Hansen and I had to figure as ladies. Pettersen was indefatigable. He faithfully and solemnly vowed that if he has a pair of boots to his feet when he gets home he will dance as long as the soles hold together.

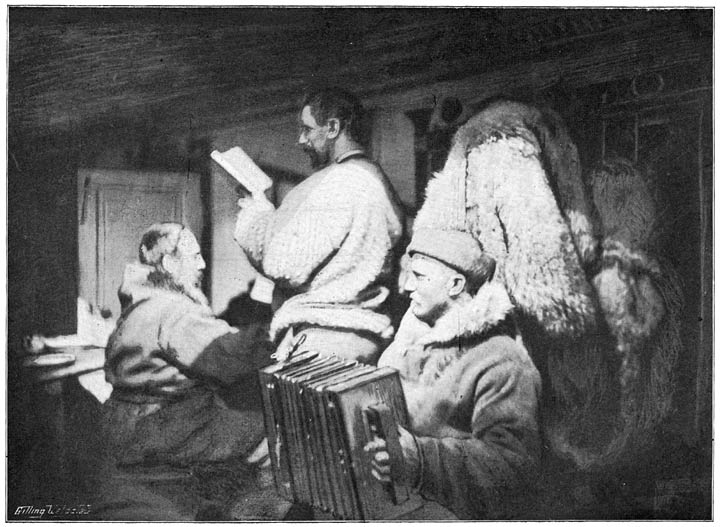

Musical Entertainment in the Saloon

(From a photograph)

“Day after day, as we progressed with a rattling wind, first from S.E. and later on E.S.E. and E., we felt more anxious to know how far we had got; but there had always been a snow-storm or a cloudy sky, so that we could not make any observations. We were all confident that we must have got a long way up north, but how far beyond the 83d degree no one could tell. Suddenly Hansen was called on deck this afternoon by the news that the stars were visible overhead. [37]All were on the tiptoe of expectation. But when he came down he had only observed one star, which, however, was so near the meridian that he could calculate that, at any rate, we were north of 83° 20′ north latitude, and this communication was received with shouts of joy. If we were not yet in the most northerly latitude ever reached by man, we were, at all events, not far from it. This was more than we had expected, and we were in high spirits. Yesterday, being ‘the Second Christmas-day,’ of course, both on this account and because it was Juell’s birthday, we had a special dinner, with oxtail soup, pork cutlets, red whortleberry preserve, cauliflowers, fricandeau, potatoes, preserved currants, also pastry, and a wonderful iced-almond cake with the words ‘Glædelig Jul’ (A Merry Christmas) on it, from Hansen, baker, Christiania, and then malt extract. We cannot complain that we are faring badly here. About 4 o’clock this morning the vessel received a violent shock which made everything tremble, but no noise of ice-packing was to be heard. At about half-past five I heard at intervals the crackling and crunching of the pack-ice which was surging in the lane ahead. At night similar noises were also heard; otherwise the ice was quiet, and the crack on the port-side has closed up tight again.

“Friday, December 28th. I went out in the morning to have a look at the crack on the port side which has now widened out so as to form an open lane. Of [38]course, all the dogs followed me, and I had not got far when I saw a dark form disappear. This was ‘Pan,’ who rolled down the high steep edge of the ice and fell into the water. In vain he struggled to get out again; all around him there was nothing but snow slush, which afforded no foothold. I could scarcely hear a sound of him, only just a faint whining noise now and then. I leaned down over the edge in order to get near him, but it was too high, and I very nearly went after him head-first; all that I could get hold of was loose fragments of ice and lumps of snow. I called for a seal-hook, but before it was brought to me ‘Pan’ had scrambled out himself, and was leaping to and fro on the floe with all his might to keep himself warm, followed by the other dogs, who loudly barked and gambolled about with him, as though they wished to demonstrate their joy at his rescue. When he fell in they all rushed forward, looking at me and whining; they evidently felt sorry for him and wished me to help him. They said nothing, but just ran up and down along the edge until he got out. At another moment, perhaps, they may all unite in tearing him to pieces; such is canine and human nature. ‘Pan’ was allowed to dry himself in the saloon all the afternoon.

“A little before half-past nine to-night the vessel received a tremendous shock. I went out, but no noise of ice-packing could be heard. However, the wind howled so in the rigging that it was not easy to distinguish [39]any other sound. At half-past ten another shock followed; later on, from time to time, vibrations were felt in the vessel, and towards half-past eleven the shocks became stronger. It was clear that the ice was packing at some place or other about us, and I was just on the point of going out when Mogstad came to announce that there was a very ugly pressure-ridge ahead. We went out with lanterns. Fifty-six paces from the bow there extended a perpendicular ridge stretching along the course of the lane, and there was a terrible pressure going on at the moment. It roared and crunched and crackled all along; then it abated a little and recurred at intervals, as though in a regular rhythm; finally it passed over into a continuous roar. It seemed to be mostly newly frozen ice from the channels which had formed this ridge; but there were also some ponderous blocks of ice to be seen among it. It pressed slowly but surely forward towards the vessel; the ice had given way before it to a considerable distance and was still being borne down little by little. The floe around us has cracked, so that the block of ice in which the vessel is embedded is smaller than it was. I should not like to have that pressure-ridge come in right under the nose of the Fram, as it might soon do some damage. Although there is hardly any prospect of its getting so far, nevertheless I have given orders to the watch to keep a sharp lookout; and if it comes very near, or if the ice should crack under us, he is to call me. Probably [40]the pressure will soon abate, as it has now kept up for several hours. At this moment (12.45 A.M.) there have just been some violent shocks, and above the howling of the wind in the rigging I can hear the roar of the ice-pressure as I lie in my berth.” [41]

Chapter II

The New Year, 1895

“Wednesday, January 2, 1895. Never before have I had such strange feelings at the commencement of the new year. It cannot fail to bring some momentous events, and will possibly become one of the most remarkable years in my life, whether it leads me to success or to destruction. Years come and go unnoticed in this world of ice, and we have no more knowledge here of what these years have brought to humanity than we know of what the future ones have in store. In this silent nature no events ever happen; all is shrouded in darkness; there is nothing in view save the twinkling stars, immeasurably far away in the freezing night, and the flickering sheen of the aurora borealis. I can just discern close by the vague outline of the Fram, dimly standing out in the desolate gloom, with her rigging showing dark against the host of stars. Like an infinitesimal speck, the vessel seems lost amidst the boundless expanse of this realm of death. Nevertheless, under her deck there is a snug and cherished home for thirteen men undaunted by the majesty of this realm. In there, life is freely pulsating, [42]while far away outside in the night there is nothing save death and silence, only broken now and then, at long intervals, by the violent pressure of the ice as it surges along in gigantic masses. It sounds most ominous in the great stillness, and one cannot help an uncanny feeling as if supernatural powers were at hand, the Jötuns and Rimturser (frost-giants) of the Arctic regions, with whom we may have to engage in deadly combat at any moment; but we are not afraid of them.

“I often think of Shakespeare’s Viola, who sat ‘like Patience on a monument.’ Could we not pass as representatives of this marble Patience, imprisoned here on the ice while the years roll by, awaiting our time? I should like to design such a monument. It should be a lonely man in shaggy wolfskin clothing, all covered with hoar-frost, sitting on a mound of ice, and gazing out into the darkness across these boundless, ponderous masses of ice, awaiting the return of daylight and spring.

“The ice-pressure was not noticeable after 1 o’clock on Friday night until it suddenly recommenced last night. First I heard a rumbling outside, and some snow fell down from the rigging upon the tent roof as I sat reading; I thought it sounded like packing in the ice, and just then the Fram received a violent shock, such as she had not received since last winter. I was rocked backward and forward on the chest on which I was sitting. Finding that the trembling and rumbling continued, I went out. There was a loud roar of ice-packing [43]to the west and northwest, which continued uniformly for a couple of hours or so. Is this the New-year’s greeting from the ice?

“We spent New-year’s-eve cozily, with a cloudberry punch-bowl, pipes, and cigarettes. Needless to say, there was an abundance of cakes and the like, and we spoke of the old and the new year and days to come. Some selections were played on the organ and violin. Thus midnight arrived. Blessing produced from his apparently inexhaustible store a bottle of genuine ‘linje akkevit’ (line eau-de-vie), and in this Norwegian liquor we drank the old year out and the new year in. Of course there was many a thought that would obtrude itself at the change of the year, being the second which we had seen on board the Fram, and also, in all probability, the last that we should all spend together. Naturally enough, one thanked one’s comrades, individually and collectively, for all kindness and good-fellowship. Hardly one of us had thought, perhaps, that the time would pass so well up here. Sverdrup expressed the wish that the journey which Johansen and I were about to make in the coming year might be fortunate and bring success in all respects. And then we drank to the health and well-being in the coming year of those who were to remain behind on board the Fram. It so happened that just now at the turn of the year we stood on the verge of an entirely new world. The wind which whistled up in the rigging overhead was not only wafting us on to [44]unknown regions, but also up into higher latitudes than any human foot had ever trod. We felt that this year, which was just commencing, would bring the culminating-point of the expedition, when it would bear its richest fruits. Would that this year might prove a good year for those on board the Fram; that the Fram might go ahead, fulfilling her task as she has hitherto done; and in that case none of us could doubt that those on board would also prove equal to the task intrusted to them.

“New-year’s-day was ushered in with the same wind, the same stars, and the same darkness as before. Even at noon one cannot see the slightest glimmer of twilight in the south. Yesterday I thought I could trace something of the kind; it extended like a faint gleam of light over the sky, but it was yellowish-white, and stretched too high up; hence I am rather inclined to think that it was an aurora borealis. Again to-day the sky looks lighter near the edge, but this can scarcely be anything except the gleam of the aurora borealis, which extends all round the sky, a little above the fog-banks on the horizon, and which is strongest at the edge. Exactly similar lights may be observed at other times in other parts of the horizon. The air was particularly clear yesterday, but the horizon is always somewhat foggy or hazy. During the night we had an uncommonly strong aurora borealis; wavy streamers were darting in rapid twists over the southern sky, their rays reaching to the zenith, and beyond [45]it there was to be seen for a time a band in the form of a gorgeous corona, casting a reflection like moonshine across the ice. The sky had lit up its torch in honor of the new year—a fairy dance of darting streamers in the depth of night. I cannot help often thinking that this contrast might be taken as typical of the Northman’s character and destiny. In the midst of this gloomy, silent nature, with all its numbing cold, we have all these shooting, glittering, quivering rays of light. Do they not typify our impetuous ‘spring-dances,’ our wild mountain melodies, the auroral gleams in our souls, the rushing, surging, spiritual forces behind the mantle of ice? There is a dawning life in the slumbering night, if it could only reach beyond the icy desert, out over the world.

“Thus 1895 comes in:

“‘Turn, Fortune, turn thy wheel and lower the proud;

Turn thy wild wheel thro’ sunshine, storm, and cloud;

Thy wheel and thee we neither love nor hate.

“‘Smile and we smile, the lords of many lands;

Frown and we frown, the lords of our own hands;

For man is man and master of his fate.’

“Thursday, January 3d. A day of unrest, a changeful life, notwithstanding all its monotony. But yesterday we were full of plans for the future, and to-day how easily might we have been left on the ice without a roof over our heads! At half-past four, in the morning a fresh rush of ice set in in the lane aft, and at five it commenced [46]in the lane on our port side. About 8 o’clock I awoke, and heard the crunching and crackling of the ice, as if ice-pressure were setting in. A slight trembling was felt throughout the Fram, and I heard the roar outside. When I came out I was not a little surprised to find a large pressure-ridge all along the channel on the port side scarcely thirty paces from the Fram; the cracks on this side extended to quite eighteen paces from us. All loose articles that were lying on the ice on this side were stowed away on board; the boards and planks which, during the summer, had supported the meteorological hut and the screen for the same were chopped up, as we could not afford to lose any materials; but the line, which had been left out in the sounding-hole with the bag-net attached to it, was caught in the pressure. Just after I had come on board again shortly before noon the ice suddenly began to press on again. I went out to have a look; it was again in the lane on the port side; there was a strong pressure, and the ridge was gradually approaching. A little later on Sverdrup went up on deck, but soon after came below and told us that the ridge was quickly bearing down on us, and a few hands were required to come up and help to load the sledge with the sounding apparatus, and bring it round to the starboard side of the Fram, as the ice had cracked close by it. The ridge began to come alarmingly near, and, should it be upon us before the Fram had broken loose from the ice, matters might become very [47]unpleasant. The vessel had now a greater list to the port side than ever.

“During the afternoon various preparations were made to leave the ship if the worst should happen. All the sledges were placed ready on deck, and the kayaks were also made clear; 25 cases of dog-biscuits were deposited on the ice on the starboard side, and 19 cases of bread were brought up and placed forward; also 4 drums, holding altogether 22 gallons of petroleum, were put on deck. Ten smaller-sized tins had previously been filled with 100 litres of snowflake oil, and various vessels containing gasoline were also standing on deck. As we were sitting at supper we again heard the same crunching and crackling noise in the ice as usual, coming nearer and nearer, and finally we heard a crash proceeding from right underneath where we sat. I rushed up. There was a pressure of ice in the lane a little way off, almost on our starboard beam. I went down again, and continued my meal. Peter, who had gone out on the ice, soon after came down and said, laughing as usual, that it was no wonder we heard some crackling, for the ice had cracked not a sledge-length away from the dog-biscuit cases, and the crack was extending abaft of the Fram. I went out, and found the crack was a very considerable one. The dog-biscuit cases were now shifted a little more forward for greater safety. We also found several minor cracks in the ice around the vessel. I then went down and had a pipe and a pleasant chat with Sverdrup [48]in his cabin. After we had been sitting a good while the ice again began to crack and jam. I did not think that the noise was greater than usual; nevertheless, I asked those in the saloon, who sat playing halma, whether there was any one on deck; if not, would one of them be kind enough to go and see where the ice was packing. I heard hurried steps above; Nordahl came down and reported that it was on the port side, and that it would be best for us to be on deck. Peter and I jumped up and several followed. As I went down the ladder Peter called out to me from above: ‘We must get the dogs out; see, there is water on the ice!’ It was high time that we came; the water was rushing in and already stood high in the kennel. Peter waded into the water up to his knees and pushed the door open. Most of the dogs rushed out and jumped about, splashing in the water; but some, being frightened, had crept back into the innermost corner and had to be dragged out, although they stood in water reaching high up their legs. Poor brutes, it must have been miserable enough, in all conscience, to be shut up in such a place while the water was steadily rising about them, yet they are not more noisy than usual.

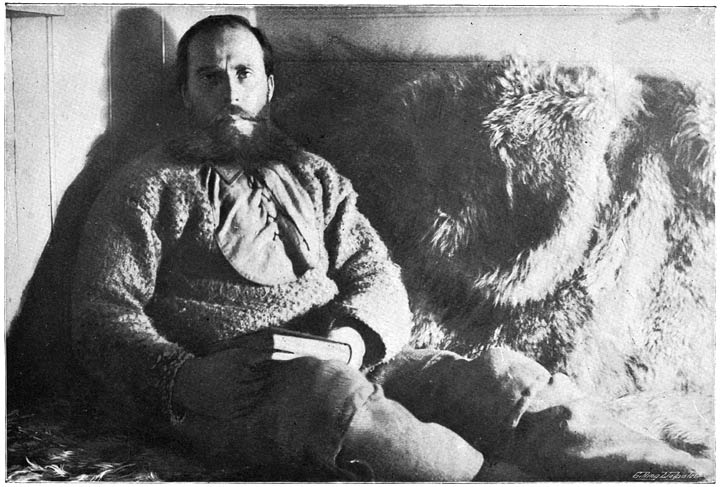

Captain Sverdrup in His Cabin

(From a photograph)

“The dogs having been put in safety, I walked round the Fram to see what else had happened. The ice had cracked along her to the fore, near the starboard bow; from this crack the water had poured aft along the port side, which was weighed down by the weight of the ridge steadily pressing on towards us. The crack has just [51]passed under the middle of the portable forge, which was thus endangered, and it was therefore put on a sledge and removed to the great hummock on the starboard quarter. The pemmican—altogether 11 cases—the cases of dog-biscuits, and 19 cases of bread were conveyed to the same place. Thus we have now a complete depot lying over there, and, I trust, in entire safety, the ice being so thick that it is not likely to give way. This has brought life into the lads; they have all turned out. We took out 4 more tin cans of petroleum to the hummock, then proceeded to bring up from the hold and place on deck ready for removal 21 cases of bread, and a supply of pemmican, chocolate, butter, ‘vril-food,’ soup, etc., calculated to last us 200 days. Also tents, cooking apparatus, and the like, were got ready, so that now all is clear up there, and we may sleep securely; but it was past midnight before we had done. I still trust that it is all a false alarm, and that we shall have no occasion for these supplies now, at any rate; nevertheless, it is our duty to keep everything ready in case the unthinkable should happen. Moreover, the watch has been enjoined to mind the dogs on the ice and to keep a sharp lookout in case the ice should crack underneath our cases or the ice-pressure should recommence; if anything should happen we are to be called out at once, too early rather than too late. While I sit here and write I hear the crunching and crackling beginning again outside, so that there must still be a steady pressure on the ice. All are in the best [52]spirits; it almost appears as if they looked upon this as a pleasant break in the monotony of our existence. Well, it is half-past one, I had better turn into my bunk; I am tired, and goodness knows how soon I may be called up.

“Friday, January 4th. The ice kept quiet during the night, but all day, with some intervals, it has been crackling and settling, and this evening there have been several fits of pressure from 9 o’clock onward. For a time it came on, sometimes rather lightly, at regular intervals; sometimes with a rush and a regular roar; then it subsided somewhat, and then it roared anew. Meanwhile the pressure-ridge towers higher and higher and bears right down upon us slowly, while the pressure comes on at intervals only, and more quickly when the onset continues for a time. One can actually see it creeping nearer and nearer; and now, at 1 o’clock at night, it is not many feet—scarcely five—away from the edge of the snow-drift on the port side near the gangway, and thence to the vessel is scarcely more than ten feet, so that it will not be long now before it is upon us. Meanwhile the ice continues to split, and the solid mass in which we are embedded grows less and less, both to port and starboard. Several fissures extend right up to the Fram. As the ice sinks down under the weight of the ridge on the port side and the Fram lists more that way, more water rushes up over the new ice which has frozen on the water that rose yesterday. This is like dying by inches. Slowly but surely the [53]baleful ridge advances, and it looks as if it meant going right over the rail; but if the Fram will only oblige by getting free of the ice she will, I feel confident, extricate herself yet, even though matters look rather awkward at present. We shall probably have a hard time of it, however, before she can break loose if she does not do so at once. I have been out and had a look at the ridge, and seen how surely it is advancing! I have looked at the fissures in the ice and noted how they are forming and expanding round the vessel; I have listened to the ice crackling and crunching underfoot, and I do not feel much disposed to turn into my berth before I see the Fram quite released. As I sit here now I hear the ice making a fresh assault, and roaring and packing outside, and I can tell that the ridge is coming nearer. This is an ice-pressure with a vengeance, and it seems as if it would never cease. I do not think there is anything more that we can do now. All is in readiness for leaving the vessel, if need be. To-day the clothing, etc., was taken out and placed ready for removal in separate bags for each man.

“It is very strange; there is certainly a possibility that all our plans may be crossed by unforeseen events, although it is not very probable that this will happen. As yet I feel no anxiety in that direction, only I should like to know whether we are really to take everything on to the ice or not. However, it is past 1 o’clock, and I think the most sensible thing to do would be to turn in and [54]sleep. The watch has orders to call me when the hummock reaches the Fram. It is lucky it is moonlight now, so that we are able to see something of all this abomination.

“The day before yesterday we saw the moon for the first time just above the horizon. Yesterday it was shining a little, and now we have it both day and night. A most favorable state of things. But it is nearly 2 o’clock, and I must go to sleep now. The pressure of the ice, I can hear, is stronger again.

“Saturday, January 5th. To-night everybody sleeps fully dressed, and with the most indispensable necessaries either by his side or secured to his body, ready to jump on the ice at the first warning. All other requisites, such as provisions, clothing, sleeping-bags, etc., etc., have been brought out on the ice. We have been at work at this all day, and have got everything into perfect order, and are now quite ready to leave if necessary, which, however, I do not believe will be the case, though the ice-pressure has been as bad as it could be.

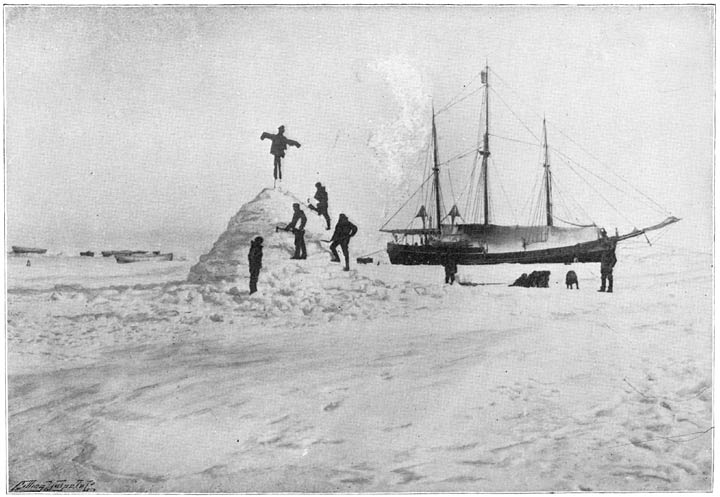

The “Fram” in the Ice.

“I slept soundly, woke up only once, and listened to the crunching and jamming and grinding till I fell asleep again. I was called at 5.30 in the morning by Sverdrup, who told me that the hummock had now reached the Fram, and was bearing down on us violently, reaching as high as the rail. I was not left in doubt very long, as hardly had I opened my eyes when I heard a thundering and crashing outside in the ice, as if doomsday had [55]come. I jumped up. There was nothing left for it but to call all hands, to put all the remaining provisions on the ice, and then put all our furs and other equipment on deck, so that they could be thrown overboard at a moment’s notice if necessary. Thus the day passed, but the ice kept quiet. Last of all, the petroleum launch, which was hanging in the davits on the port side, was lowered, and was dragged towards the great hummock. At about 8 o’clock in the evening, when we thought the ice-pressure had subsided, it started thundering and crashing again worse than ever. I hurried up. Masses of snow and ice rushed on us, high above the rail amidships and over the tent. Peter, who also came up, seized a spade and rushed forward outside the awning as far as the forepart of the half-deck, and stood in the midst of the ice, digging away, and I followed to see how matters stood. I saw more than I cared to see; it was hopeless to fight that enemy with a spade. I called out to Peter to come back, and said, ‘We had better see to getting everything out on to the ice.’ Hardly had I spoken, when it pressed on again with renewed strength, and thundered and crashed, and, as Peter said, and laughed till he shook again, ‘nearly sent both me and the spade to the deuce.’ I rushed back to the main-deck; on the way I met Mogstad, who hurried up, spade in hand, and sent him back. Running forward under the tent towards the ladder, I saw that the tent-roof was bent down under the weight of the masses of [56]ice, which were rushing over it and crashing in over the rail and bulwarks to such an extent that I expected every moment to see the ice force its way through and block up the passage. When I got below, I called all hands on deck; but told them when going up not to go out through the door on the port side, but through the chart-room and out on the starboard side. In the first place, all the bags were to be brought up from the saloon, and then we were to take those lying on deck. I was afraid that if the door on the port side was not kept closed the ice might, if it suddenly burst through the bulwarks and tent, rush over the deck and in through the door, fill the passage and rush down the [57]ladder, and thus imprison us like mice in a trap. True, the passage up from the engine-room had been cleared for this emergency, but this was a very narrow hole to get through with heavy bags, and no one could tell how long this hole would keep open when the ice once attacked us in earnest. I ran up again to set free the dogs, which were shut up in ‘Castle-garden’—an enclosure on the deck along the port bulwark. They whined and howled most dolefully under the tent as the snow masses threatened at any moment to crush it and bury them alive. I cut away the fastening with a knife, pulled the door open, and out rushed most of them by the starboard gangway at full speed.1

“All Hands on Deck!”

Meantime the hands started bringing up the bags. It was quite unnecessary to ask them to hurry up—the ice did that, thundering against the ship’s sides in a way that seemed irresistible. It was a fearful hurly-burly in the darkness; for, to cap all, the mate had, in the hurry, let the lanterns go out. I had to go down again to get something on my feet; my Finland shoes were hanging up to dry in the galley. When I got there the ice was at its worst, and the half-deck beams were creaking overhead, so that I really thought they were all coming down. [58]

“The saloon and the berths were soon cleared of bags, and the deck as well, and we started taking them along the ice. The ice roared and crashed against the ship’s side, so that we could hardly hear ourselves speak; but all went quickly and well, and before long everything was in safety.

“While we were dragging the bags along, the pressure and jamming of the ice had at last stopped, and all was quiet again as before.

“But what a sight! The Fram’s port side was quite buried under the snow; all that could be seen was the top of the tent projecting. Had the petroleum launch been hanging in the davits, as it was a few hours previously, it would hardly have escaped destruction. The davits were quite buried in ice and snow. It is curious that both fire and water have been powerless against that boat; and it has now come out unscathed from the ice, and lies there bottom upward on the floe. She has had a stormy existence and continual mishaps; I wonder what is next in store for her?

“It was, I must admit, a most exciting scene when it was at its worst, and we thought it was imperative to get the bags up from the saloon with all possible speed. Sverdrup now tells me that he was just about to have a bath, and was as naked as when he was born, when he heard me call all hands on deck. As this had not happened before, he understood there was something serious the matter, and he jumped into his clothes anyhow. [59]Amundsen, apparently, also realized that something was amiss. He says he was the first who came up with his bag. He had not understood, or had forgotten, in the confusion, the order about going out through the starboard door; he groped his way out on the port side and fell in the dark over the edge of the half-deck. ‘Well, that did not matter,’ he said; ‘he was quite used to that kind of thing;’ but having pulled himself together after the fall, and as he was lying there on his back, he dared not move, for it seemed to him as if tent and all were coming down on him, and it thundered and crashed against the gunwale and the hull as if the last hour had come. It finally dawned on him why he ought to have gone out on the starboard and not on the port side.

“All that could possibly be thought to be of any use was taken out. The mate was seen dragging along a big bag of clothes with a heavy bundle of cups fastened outside it. Later he was stalking about with all sorts of things, such as mittens, knives, cups, etc., fastened to his clothes and dangling about him, so that the rattling noise could be heard afar off. He is himself to the last.