.

THE HISTORIANS’ HISTORY OF THE WORLD

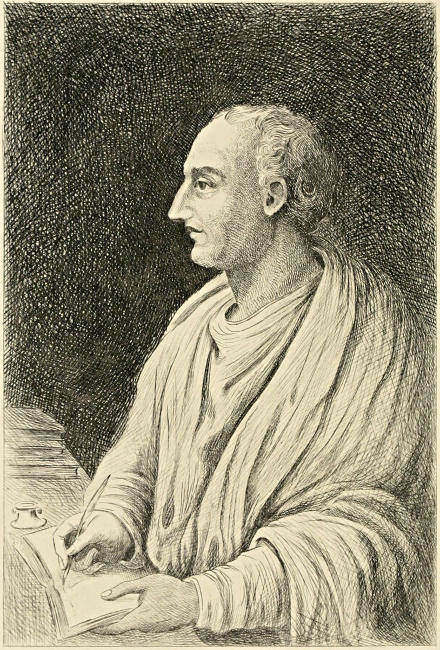

LIVY

THE HISTORIANS’

HISTORY

OF THE WORLD

A comprehensive narrative of the rise and development of nations

as recorded by over two thousand of the great writers of

all ages: edited, with the assistance of a distinguished

board of advisers and contributors,

by

HENRY SMITH WILLIAMS, LL.D.

IN TWENTY-FIVE VOLUMES

VOLUME V—THE ROMAN REPUBLIC

The Outlook Company

New York

The History Association

London

1904

Copyright, 1904,

By HENRY SMITH WILLIAMS.

All rights reserved.

Contributors, and Editorial Revisers.

- Prof. Adolf Erman, University of Berlin.

- Prof. Joseph Halévy, College of France.

- Prof. Thomas K. Cheyne, Oxford University.

- Prof. Andrew C. McLaughlin, University of Michigan.

- Prof. David H. Müller, University of Vienna.

- Prof. Alfred Rambaud, University of Paris.

- Prof. Eduard Meyer, University of Berlin.

- Dr. James T. Shotwell, Columbia University.

- Prof. Theodor Nöldeke, University of Strasburg.

- Prof. Albert B. Hart, Harvard University.

- Dr. Paul Brönnle, Royal Asiatic Society.

- Dr. James Gairdner, C.B., London.

- Prof. Ulrich von Wilamowitz Möllendorff, University of Berlin.

- Prof. H. Marnali, University of Budapest.

- Dr. G. W. Botsford, Columbia University.

- Prof. Julius Wellhausen, University of Göttingen.

- Prof. Franz R. von Krones, University of Graz.

- Prof. Wilhelm Soltau, Zabern University.

- Prof. R. W. Rogers, Drew Theological Seminary.

- Prof. A. Vambéry, University of Budapest.

- Prof. Otto Hirschfeld, University of Berlin.

- Baron Bernardo di San Severino Quaranta, London.

- Prof. F. York Powell, Oxford University.

- Dr. John P. Peters, New York.

- Dr. S. Rappoport, School of Oriental Languages, Paris.

- Prof. Hermann Diels, University of Berlin.

- Prof. C. W. C. Oman, Oxford University.

- Prof. I. Goldziher, University of Vienna.

- Prof. W. L. Fleming, University of West Virginia.

- Prof. R. Koser, University of Berlin.

CONTENTS

| VOLUME V | |

| ROME | |

| PAGE | |

| INTRODUCTORY ESSAYS | |

| The World Influence of Early Rome. By Dr. Eduard Meyer | 1 |

| The Scope and Development of Early Roman History. By Dr. Wilhelm Soltau | 11 |

| BOOK I.—EARLY ROMAN HISTORY TO THE FALL OF THE REPUBLIC | |

| Introduction | 25 |

| CHAPTER I | |

| Land and People | 43 |

| The land of Italy, 44. Early population of Italy, 48. Beginnings of Rome and the primitive Roman commonwealth, 51. | |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Early Legends of Rome—Æneas and Romulus (ca. 753-716 B.C.) | 58 |

| The Æneas legend, 59. The Ascanius legend, 60. The legend of Romulus and Remus, 61. The rape of the Sabines, 63. A critical study of the legends, 66. Explanation of the Æneas legend, 69. The Romulus legend examined, 70. | |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Legendary History of the Kings (ca. 716-510 B.C.) | 75 |

| Numa Pompilius, 75. Tullus Hostilius, 76. The combat of the Horatii and the Curiatii, 77. Ancus Marcius, 79. L. Tarquinius Priscus, 80. Servius Tullius, 82. [viii]Lucius Tarquinius the Tyrant, 83. | |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| The Banishment of the Kings—Criticisms of Monarchial History (ca. 510 B.C.) | 85 |

| Tarquinius consults the oracle, 85. The rape of Lucretia, 86. Niebuhr on the story of Lucretia, 87. The banishment of Tarquinius, 88. Porsenna’s war upon the Romans; the story of Horatius at the bridge, as told by Dionysius, 90. Caius Mucius and King Porsenna, 92. Battle of Lake Regillus, 93. The myths of the Roman kings critically examined, 95. The historical value of the myths, 100. | |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Civilisation of the Regal Period (ca. 753-510 B.C.) | 103 |

| Organisation of the state, 103. The status of the monarchy, 105. Religion, 107. Constitution, 107. The organisation of the army, 111. Classes of foot soldiers, 112. Popular institutions, 113. The wealth of the Romans and its sources, 115. Roman education, 117. Morals and politics of the age, 118. The fine arts, 119. | |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| The First Century of the Republic (510-391 B.C.) | 121 |

| Plebeians and patricians, 123. Spurius Cassius and the first Agrarian Law, 129. The institution of the decemvirate, 131. The story of Virginia told by Dionysius, 132. Fall of the decemvirate, 138. The Canuleian Law, 140. External wars, 142. Legends of the Volscian and Æquian wars, 145. Coriolanus and the Volscians, 145. Critical examination of the story of Coriolanus, 148. Cincinnatus and the Æquians, 149. Critical examination of the story of Cincinnatus, 151. The Fabian Gens and the Veientines, 152. | |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| The Invasion of the Gauls and its Sequel (391-351 B.C.) | 154 |

| The Gauls, 155. Livy’s account of the Gauls in Rome, 156. Other accounts of the departure of the Gauls, 165. Niebuhr on the conduct of the Romans, 166. Sequel of the Gallic War, 167. The Licinian rogations, 170. Equalisation of the two orders, 172. External affairs, 175. | |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| The Conquest of Central Italy (423-280 B.C.) | 178 |

| The Samnites, 178. The First Samnite War, 180. The Latin War, 183. The Second Samnite War, 186. The Third Samnite and Etruscan wars, 194. Lucanian, Gallic, and Etruscan wars, 199. | |

| [ix]CHAPTER IX | |

| The Completion of the Italian Conquest (281-265 B.C.) | 201 |

| Pyrrhus in Italy, 203. The final reduction of Italy, 209. Government of the acquired territory, 210. Prefectures; municipalities, 211. Colonies; free and confederate states, 212. | |

| CHAPTER X | |

| The First Punic War (326-218 B.C.) | 215 |

| Causes of the First Punic War, 217. The war begins, 219. First period, 219. Second period, 221. Polybius’ account of Roman affairs, 224. Third period, 230. Events between the First and Second Punic wars, 233. Hamilcar and Hannibal, 237. | |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| First Half of the Second Punic War (218-211 B.C.) | 241 |

| First period, 241. Polybius’ account of the crossing of the Alps, 244. Hannibal in Italy, 249. Second period, 260. | |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| Close of the Second Punic War (210-202 B.C.) | 269 |

| Third period, 269. The death of Hasdrubal described by Polybius, 276. Rejoicing at Rome; Nero’s inhumanity and triumph, 277. The fourth and last period of the war, 278. The character of Scipio, 278. Scipio in Spain, 279. Scipio returns to Rome, 283. Scipio invades Africa, 284. The battle of Zama described by Polybius, 287. Terms dictated to Carthage; Scipio’s triumph, 292. An estimate of Hannibal, 294. | |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| The Macedonian and Syriac Wars and the Third Punic War (200-131 B.C.) | 296 |

| The Macedonian War; war with Antiochus III, 296. Affairs of Carthage, 304. Outbreak of the Third Punic War, 305. Appian’s account of the destruction of Carthage, 310. The oration of Hasdrubal’s wife; Scipio’s moralising, 312. Plundering the city, 313. Sacrifices and the triumph, 314. The Achæan War, 314. Spanish wars: fall of Numantia, 317. Florus on the fall of Numantia, 321. First Slave War in Sicily, 322. The war against the slaves, 325. | |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| Civilisation at the End of the Period of Conquest | 327 |

| Organisation of the government, 327. The army, 329. Polybius on Greek and Roman battle-orders, 329. The senate, 332. The centuriate assembly, 334. The assembly of the tribes, 334. Justice, 337. Provincial government, 337. Taxation, 338. Social conditions: the aristocracy and the people, 340. Slaves and freemen, 343. The Roman family: women and marriage, 346. Religion, 350. Treatment of other nations, 355. The fine arts, 355. Literature, 358. | |

| [x]CHAPTER XV | |

| The Gracchi and their Reforms (137-121 B.C.) | 359 |

| Tiberius Gracchus, 359. Return and death of Scipio the Younger, 366. Caius Gracchus and his times, 371. | |

| CHAPTER XVI | |

| The Jugurthine and Other Wars (123-101 B.C.) | 381 |

| The Jugurthine War, 383. Sallust’s account of Jugurtha at Rome, 385. A war of bribery, 387. Metellus in command, 388. Marius appears as commander, 389. Plutarch on Jugurtha’s death, 391. The Cimbrians and the Teutons, 392. The Second Slave War, 399. | |

| CHAPTER XVII | |

| The Beginning of Civil Strife (102-88 B.C.) | 401 |

| The sixth consulate of Marius, 402. Claims of the Latins and Italians to the civitas, 405. The Social War, 413. Marius assumes the command, 415. | |

| CHAPTER XVIII | |

| Marius and Sulla (92-82 B.C.) | 420 |

| The First Mithridatic War, 421. The First Civil War, 422. Ihne’s estimate of Marius, 431. Sulla in Greece, 432. The return of Sulla; and the Second Civil War, 434. The proscriptions, 438. | |

| CHAPTER XIX | |

| The Dictatorship of Sulla (81-79 B.C.) | 442 |

| Sulla’s legislation, 446. Abdication of Sulla, 446. Rome’s debt to Sulla, 448. The Roman provinces, 450. The career of Verres, 454. | |

| CHAPTER XX | |

| The Rise of Pompey (78-61 B.C.) | 457 |

| Lepidus and Sertorius, 457. The war of the Gladiators, 460. The consulship of Pompey and Crassus, 461. Pompey subdues the Cilician pirates, 464. The Second and Third Mithridatic wars, 467. The Armenian War, 469. The end of Mithridates, 473. Pompey in Jerusalem, 474. | |

| CHAPTER XXI | |

| The Conspiracy of Catiline (67-61 B.C.) | 475 |

| Marcus Porcius Cato, 475. Caius Julius Cæsar, 477. L. Sergius Catilina and his times, 480. The conspiracy, 483. Cæsar and the conspiracy, 488. The rise of Julius Cæsar, 494. The return of Pompey, 497. | |

| [xi]CHAPTER XXII | |

| Cæsar and Pompey (60-50 B.C.) | 501 |

| The first triumvirate, 501. Clodius exiles Cicero, 504. The recall of Cicero, 506. Second consulate of Pompey and Crassus, 508. The Parthian War of Crassus, 509. Anarchy at Rome, 511. Pompey sole consul, 513. The Gallic wars, 514. The battle with the Nervii, 516. The sea fight with the Veneti, 520. The massacre of the Germans, 522. The Roman army meets the Britons, 523. | |

| CHAPTER XXIII | |

| Cæsar at War against Pompey (60-48 B.C.) | 528 |

| The war between Cæsar and Pompey, 529. Cæsar crosses the Rubicon, 532. Cæsar’s serious position, 534. Cæsar lord from Rome to Spain, 535. Cæsar in Greece, 536. Appian describes the battle of Dyrrhachium, 537. Pharsalia, 541. | |

| CHAPTER XXIV | |

| From Pharsalia to the Death of Cato (48-46 B.C.) | 544 |

| Cæsar in Egypt, 544. The war with Pharnaces, 551. Cæsar returns to Rome, 552. The African War, 554. Sallust’s comparison of Cæsar and Cato, 558. | |

| CHAPTER XXV | |

| The Closing Scenes of Cæsar’s Life (46-44 B.C.) | 560 |

| The end of the African war, 560. The return to Rome, 562. Cæsar’s triumphs, 563. The last campaign, 566. The last triumph, 569. Cæsar’s reforms, 572. Cæsar’s life in Rome, 575. Events leading to the conspiracy, 578. The conspiracy, 579. The assassination, 581. Appian’s account of Cæsar’s last days, 583. | |

| CHAPTER XXVI | |

| The Personality and Character of Cæsar | 588 |

| Appian compares Cæsar with Alexander, 599. Mommsen’s estimate of Cæsar’s character, 602. Mommsen’s estimate of Cæsar’s work, 607. | |

| CHAPTER XXVII | |

| The Last Days of the Republic (44-29 B.C.) | 609 |

| Cæsar’s will and funeral, 610. The acts of the young Octavius, 611. The proscription, 617. Death of Cicero, 619. Brutus and Cassius, 621. Philippi, 622. Antony and Cleopatra, 624. Antony meets with reverses, 625. Octavian against Antony; the battle of Actium, 630. Death of Antony and Cleopatra, 631. An estimate of the personality of Antony, 633. | |

| [xii]CHAPTER XXVIII | |

| The State of Rome at the End of the Republic | 637 |

| A retrospective view of the republican constitution, 637. Literature, 643. The drama, 645. Poetry, 647. The fine arts, 651. Social conditions; religion, 652. | |

| Brief Reference-List of Authorities by Chapters | 655 |

PART X

THE HISTORY OF ROME FROM THE EARLIEST TIMES

TO THE YEAR 476 A.D.

BASED CHIEFLY UPON THE FOLLOWING AUTHORITIES

AMMIANUS, APPIAN, THOMAS ARNOLD, BARTHÉLEMY AUBE, AUGUSTAN HISTORY,

C. JULIUS CÆSAR, HENRY FYNES CLINTON, CICERO, DION CASSIUS, DIONYSIUS

OF HALICARNASSUS, EUTROPIUS, FLORUS, VICTOR GARDTHAUSEN, EDWARD

GIBBON, OTTO GILBERT, ADOLF HARNACK, G. F. HERTZBERG,

HERODIAN, OTTO HIRSCHFELD, THOMAS HODGKIN, KARL

HOECK, WILHELM IHNE, JORDANES (JORNANDES),

JOSEPHUS, GEORGE CORNEWALL LEWIS,

H. G. LIDDELL, LIVY, JOACHIM MARQUARDT, CHARLES MERIVALE, EDUARD MEYER,

THEODOR MOMMSEN, MONUMENTUM ANCYRANUM, CORNELIUS NEPOS,

B. G. NIEBUHR, PLINY THE ELDER, PLINY THE YOUNGER,

PLUTARCH, POLYBIUS, L. VON RANKE, SALLUST,

WILHELM SOLTAU, STRABO, SUETONIUS,

TACITUS, TILLEMONT, VELLEIUS,

GEORG WEBER, ZOSIMUS

TOGETHER WITH A CHARACTERISATION OF

THE WORLD INFLUENCE OF EARLY ROME

BY

EDUARD MEYER

A STUDY OF

THE SCOPE AND DEVELOPMENT OF EARLY ROMAN HISTORY

BY

WILHELM SOLTAU

A SKETCH OF

THE EARLY ROMAN EMPIRE

BY

OTTO HIRSCHFELD

AND A SUMMARY OF

THE RELATIONS OF THE ROMAN STATE AND THE EARLY CHRISTIAN CHURCH

BY

ADOLF HARNACK

WITH ADDITIONAL CITATIONS FROM

J. J. AMPÈRE, FRIEDRICH BLUHME, GEORGE W. BOTSFORD, A. BOUCHE-LECLERCQ,

KURT BREYSIG, R. W. BROWN, R. BURN, DION CHRYSOSTOM, JACQUES FRANÇOIS

DENIS, JEAN VICTOR DURUY, T. H. DYER, EPICTETUS, A. ESMEIN,

E. A. FREEMAN, G. C. FISKE, GABRIEL H. GAILLARD,

OLIVER GOLDSMITH, ALBERT GUELDENPENNING,

OSCAR JÄGER, JULIAN, THOMAS KEIGHTLEY,

GEORGE LONG, J. N. MADVIG,

MARCUS AURELIUS, VALERIUS MAXIMUS, ARTHUR MURPHY, PHILON, S. REINHARDT,

J. ERNEST RENAN, JOHANN HEINRICH KARL FRIEDRICH HERMANN SCHILLER,

K. W. F. VON SCHLEGEL, F. C. SCHLOSSER, ALBERT SCHWEGLER, L. ANNÆUS

SENECA, M. ANNÆUS SENECA, J. Y. SHEPPARD, JAMES SIME, H. W.

STÖLL, H. TAINE, AMÉDÉE THIERRY, VIRGIL, L. WIEGANDT,

EDUARD VOX WIETERSHEIM, H. S. WILLIAMS, R. H.

WRIGHTSON, XIPHILINUS, K. S. ZACHARIÆ

VON LINGENTHAL

THE WORLD INFLUENCE OF EARLY ROME

Written Specially for the Present Work

By DR. EDUARD MEYER

Professor of Ancient History in the University of Berlin.

It might have been supposed that with the death of Alexander the political connection between the eastern and western halves of the Mediterranean, which had subsisted throughout the whole course of Greek history, was severed except for such occasional and superficial points of contact as, in the nature of things, had never been wholly lacking. As a matter of fact, the West was left to its own devices. But it presently became evident that the development which there took place, untroubled by interference from without, was fraught with consequences of the utmost moment to the Hellenistic political system. By abstaining from peremptory interference while such interference was yet possible, the Macedonian kingdoms permitted a power to arise in Italy so strong that in a very short time it proceeded to aim a fatal blow at their own existence.

This new power did not take its rise among those who had hitherto been the most formidable foes of Greece—the Sabello-Oscan tribes, whom Plato dreaded. These last were a race of warlike mountaineers living under a free system of tribal government, something like the Swiss of the later Middle Ages, except that cavalry, as well as infantry, played an important part in their armies. Like the Swiss, they strove to extend their borders on every side beyond the narrow limits of their native land. But they lacked what the Swiss of the Four Cantons gained by their league with Berne and Zurich—a steady political aim; tribe jostled tribe, the remoter endeavouring to wrest from the nearer what the latter had won. Thus, though they might subjugate cities of Greece, they were incapable of creating a great homogeneous state. The Caraceni, Pentri, Caudini, and Hirpini, the four tribes of the mountain tract about the sources of the Volturnus and its tributaries, were the only ones which constituted a compact federation. After the middle of the fourth century these tribes began to press forward in every direction, against the Apulians to the east, the Lucanians to the south, the Campanians, Sidicinians, and Volscians to the west. But there they were confronted by a power which was destined to prove greater than they.

As early as the sixth century, during the Etruscan period, the city of Rome on the Tiber had grown into a large and important community. After the overthrow of foreign dominion and the fall of the monarchy, it maintained its supremacy over at least the majority of the country townships of the little Latin nation, which laboriously warded off the attacks of its neighbours under Roman hegemony. Not till about the year 400 did it succeed in driving the Æqui and Volscians back into their mountain fastnesses; and in 388 it took the neighbouring Etruscan city of Veii. The great Celtic invasion brought it to the verge of ruin; but having survived this peril it maintained its former predominance after the withdrawal of the enemy. With the Greeks it was on friendly terms; from of old, Greek civilisation had found almost as ready acceptance among the Latins as among the Etruscans, and in the struggle with the latter people Latins and Greeks had fought side by side. The middle of the fourth century witnessed a great expansion of Roman power; the Romans conquered the Volscians and several refractory Latin cities, and vanquished their Etruscan neighbours, and in the year 350 the Etruscan city of Cære joined the Roman confederacy. At the same time Rome extended her dominion in the valley of the Liris and towards the coast; and in the latter quarter the great city of Capua (together with Cumæ, now an Oscan city, and many others) threw themselves into the arms of Rome for protection against the Samnites. Soon after, in 336-334, Capua and the Latin towns, which had revolted, were completely subjugated, and most of them incorporated into the Roman body politic. Peace had been maintained up to this time with the Samnites, to whom the south of the Campania and the valley of the upper Liris had been abandoned; but when, in 325, Rome gained a footing in Fregellæ and took the Greeks of Naples under her protection, an open conflict broke out between the two states, each of which was doing its utmost to extend its borders in Italy.

In spite of the higher level of civilisation to which it had risen, the state of Rome, like that of the Samnites, was a state of farmers. But it possessed what the Samnite tribal organisation lacked, a superior political system, which gave it the advantage of the municipal form of government, on exactly the same lines as the municipal republics of Greece. But with this municipal organisation it combined (and therein lay the secret of its success) a capacity for expansion and an ever increasing extension of civil rights which offers the strongest contrast to the churlish spirit of the Greek cities. In the latter, purity of descent and the exclusion of all foreigners from civil rights was an axiom of political life, to which radical democracies, like Athens, clung even more tenaciously than the rest; and the consequence was that every success abroad led to the subjugation of the vanquished under the yoke of the ruling city. Rome, on the contrary, for all her conquests, made no subjects in Italy. In her own vicinity, and in Latium first of all, conquered communities were usually admitted to the Roman political confederacy on equal terms, and allowed to retain local autonomy (as municipia) under Roman supervision. She extended the same system far into middle Italy; the franchise and the right of voting in the Roman popular assemblies (comitia) being withheld only from communities of alien language, like the Etruscan Cærites, and the Campanians of Capua. In other cases, when Rome had vanquished a foe she took possession of a portion of the public lands, and established citizens there as settlers to cultivate the soil; the rest of the citizens retained complete liberty and political autonomy (Rome, however, altering the system of[3] government according to her own good pleasure and taking care that the administration fell into the hands of her own adherents), but were pledged by an everlasting covenant to follow the Roman standards as free allies. Moreover, Rome had founded colonies in the heart of the enemy’s country, daughter-cities organised as independent municipalities, which occupied the same position towards her as formerly (before 336) the cities of the Latin League, and were consequently known as Latin colonies. By this organisation Rome not only maintained possession, in every instance, of the territory she had won, but made provision for a constant supply of sound and capable peasantry, from whose ranks the army was recruited. While retaining, in her political administration, the form of a city, she had in effect far outgrown its limitations and become a great state, with all its forces at the disposal of the government unconditionally. To this circumstance it is due that while the constitution recognised the absolute sovereignty of the people (the abolition of the whole body of aristocratic privilege belongs to this very period)[1] the government remained vested in the hands of the great families of patrician and plebeian descent, and the dignity of office, which was degraded to a mere phantom in the Greek democracies, remained virtually undiminished in Rome. The interests of the farming class and of the dominant families went hand in hand; the former profited by the agrarian policy of expansion on which the latter insisted, and every success abroad, no matter at what cost, consolidated and increased the strength of the community, and led a step farther on the road to supreme dominion.

In numbers, military capacity, and martial ardour, the Samnites were at least a match for the Romans, their generals were possibly superior to those of Rome in ability; the Samnites won more victories than their adversaries in the open field. The Samnites’ farming communities perished through the defects of their political organisation; they could not make a breach in the solid fabric of the might of Rome, nor master the Roman fortresses, even though they might capture one now and again; while, thanks to her superior civilisation and the supplies of money, provisions, and war material furnished by the various cities within her territory, Rome was able to carry on war much more continuously than the Samnite farmer, whose armies could not remain in the field for more than a few weeks at a time, because, like the Peloponnesians in the war with Athens, their stock of provisions was exhausted and they were obliged to return home to till their land. In addition to this disadvantage, all their neighbouring tribes, the clans in the Abruzzi, the Apulians, and for a while even the Lucanians, took the part of Rome.

In spite of all their successes in the field the Samnites realised that they could not permanently withstand the Romans single-handed; they endeavoured to drag the other nations of Italy into the contest, and thus the long conflict took on the character of a decisive struggle for the sovereignty of Italy. Twice the Samnites succeeded in bringing about a great coalition; in 308 the Etruscans flung themselves upon Rome, in 295 the Samnite troops joined the hordes of the Celts in Umbria, while the Etruscans flew to arms once more. The Romans remained victors on both occasions, and the great battle of Sentinum in 295 decided the fate of Italy. When the war ended, in the year 290, Rome was the dominant power in Italy, and the submission of such portions of the country as still retained their independence was[4] merely a matter of time. It was too late then for Tarentum to step into the breach and invoke the aid of Pyrrhus, king of Epirus, too late for the latter to resume the strife in the old spirit of the struggle of Greece against the Italians and Carthaginians. The particularist temper of the Greeks brought his successes to nought as soon as they were won; for all his superior ability as a commander, and though he defeated the Romans, he could not but recognise at once the superiority of their military system. Though he advanced to the frontiers of Latium and from afar saw the enemy’s capital at his feet, he could not shatter the framework of the Roman state, and he ultimately succumbed to the Romans on the battle-field of Beneventum (275).

Rome had now completed the conquest of Italy up to the margin of the valley of the Po, and had everywhere inaugurated the system sketched in broad outline above. How firmly she had welded it was proved by the fiery test of the war of Hannibal. There was no lack of the particularist spirit even in Italy, and the numerous nationalities which inhabited the peninsula, none of whom understood the language of the others, had no such common bond as knit the various tribes of Greece together. In the territory over which Rome ruled in 264, no less than six different languages were spoken, without counting the Ligurians, Celts, and Veneti. But Rome, by repressing all open insubordination with inflexible energy while at the same time pursuing a liberal policy with regard to the interests of the dependent communities and leaving scope for local autonomy as long as it was not dangerous to herself, did more than create a political entity; from this germ begins to grow a sentiment of Italian nationality that reaches beyond racial differences, and the new nation of the Italians or toga-wearers (togati) has come to the birth.

The mainspring of Roman success was the policy of agrarian expansion, and the farmers were the first to profit by it. This fact rendered impossible the development of a municipal democracy after the Greek model (such as Appius Claudius had attempted to set up in 308) based upon capital, trade, and handicraft, and the masses of the urban population, with an all-powerful demagogue at its head.

From that time forward the urban population, restricted as it was to four districts, was practically overridden, as far as political rights were concerned, in the comitia tributa (with which ordinary legislation rested) by the thirty-one districts of the agricultural class. But as the state grew into a great power and its chief town into a metropolis, the urban elements could not fail to acquire increasing influence, especially the wealthy capitalists (consisting largely of freedmen and the descendants of freedmen) who managed all matters of public finance. In the comitia centuriata which were organised on the basis of a property qualification, and whose functions included the election of magistrates and the settlement of peace and war, these circles exercised very great influence, and the wealthiest found a compact organisation in the eighteen centuries of knights.

The interests of the agricultural class did not extend beyond Italy; the late wars had provided plenty of land for distribution, and if more were wanted it could be found in the territory of the Celts on the Po, the southern portion of which had been conquered as early as 282 but not yet divided. The interests of the urban elements, the capitalists, on the contrary, extended beyond the sea. To them the most pressing business of the moment was to vindicate the preponderance of the state to the outside world, to adjust their relations abroad as best suited their own interests, and to deliver Italy from foreign competition, and, above all, from Carthage;[5] and not a few of the great ruling families were allured, like the Claudii, by the tempting prospect.

Carthage and Rome had come dangerously near together during the last few decades. As long before as the year 306 the two had concluded a compact by which Rome was not to intervene in Sicily nor Carthage in Italy. The rival states had indeed united against Pyrrhus, but without ever laying aside their mutual distrust; each feared that the other might effect a lodgment within its sphere of influence. And now, in the year 264, the Oscan community of the Mamertines in Messana (whilom mercenaries of Agathocles, who had exterminated the Greek inhabitants of the city) appealed to both Carthage and Rome for aid against Hiero, the ruler of Syracuse.

Rome was thus brought face to face with the most momentous decision in her whole history. The Romans were not untroubled by moral scruples nor blind to the fact that to accede to the petition would necessarily lead to war with Carthage, since Carthage had promptly taken the city under her protection and occupied it with her troops; but the opportunity was too tempting, and if it were allowed to pass, the whole of the rich island would undoubtedly fall under the sovereignty of Carthage for evermore, and her power, formidable already, would be correspondingly increased. The senate hesitated, but the consul Appius Claudius brought the matter before the comitia centuriata, and they decided in favour of rendering assistance, and thereby in favour of war.

It was a step that could never be retraced, a step of the same incalculable consequence to Rome as the occupation of Silesia was to Prussia, or the war with Spain and the occupation of Cuba and the Philippines to the United States of America. Its immediate consequences were a struggle of twenty-four years’ duration with Carthage for the possession of Sicily, and the creation of a Roman sea power which was not merely a match for that of Carthage, but actually annihilated it; its ultimate result was the acquisition of a dominion beyond sea in which Rome for the first time bore rule over tributary subjects governed by Roman magnates and exploited by Italian capitalists. A further consequence was that the Romans took advantage of the difficulties in which Carthage was involved by a mutiny of mercenaries in 237 to wrest Sardinia and Corsica from her and at the same time once more exact a huge indemnity.

In other directions, too, Rome became more and more deeply involved in the affairs of the outside world, and consequently with the political system of Hellenic states. As in the old conflict with the Etruscans and the recent war with Carthage, so a decade later she solved in the Levant a problem which had been propounded to Greece and for the solution of which she had not been strong enough. When the pirate state of the Illyrians of Scodra extended to the coasts of Italy the ravages it had inflicted upon the Greeks, Rome took vigorous action, used her lately acquired sea power for the speedy overthrow of the pirate state (229) and planted her foot firmly on the coast of the Balkan peninsula; thereby encroaching on the sphere of influence of Macedonia, which was constrained to be a helpless spectator.

On the other hand the close amity with the court of Alexandria, which had been inaugurated after the war with Pyrrhus, was cemented; there were no grounds for antagonism between the first maritime power of the East and the first land power of the West, while, as far as their rivals were concerned, the interests of the two in both spheres went hand in hand. One result of this development was the ever readier acceptance of Greek[6] civilisation at Rome. After the conclusion of the First Punic War the Greek drama, which formed the climax of the festivals of the Hellenic world, was adopted in the popular festivals of Rome, and a Greek prisoner of war from Tarentum, Livius Andronicus by name, who translated the Greek plays into Latin, likewise introduced Greek scholarship into Rome and translated the Odyssey, the Greek reading-book. There is no need to tell how with this the development of Latin literature begins, or how Nævius the Latin, who himself had fought in the First Punic War, takes his place beside the Greek author as a Roman national poet.

In other respects, however, Rome returned to her ancient Italian policy. After the year 236 she entered upon hostilities with the Ligurians north of the Arno; in 232 the border country taken from the Gauls was partitioned and settled by Caius Flaminius. This led to another great war with the Celts (225-222), the outcome of which was the conquest of the valley of the Po—involving the acquisition of another vast region for partition and colonisation. In this war the Veneti and the Celtic tribe of the Cenomani (between the Adige and the Addua) had voluntarily allied themselves with Rome, and her dominion therefore extended everywhere to the foot of the Alps.

But meanwhile a formidable adversary had arisen. At Carthage the Roman attack and the loss of the position maintained for centuries in the islands, as well as the loss of sea power, had no doubt been keenly felt by all classes of the population. But the government, i.e., the merchant aristocracy, had accepted the arbitrament of war as final. They could not bring themselves to make the sacrifices which another campaign against Rome must cost, especially as they clearly foresaw that even if victory were won after a fiercer contest than before, it would certainly bring their own fall and the establishment of the rule of the victorious general in its train. They accordingly resigned themselves to the new state of things, and endeavoured, in spite of all changes, to maintain amicable relations with Rome, since only thus could trade and industry continue to flourish, and Carthage, despite the loss of her supremacy at sea, remain, as before, the first commercial city of the western Mediterranean.

But side by side with the government a military party had come into being, and its leader, Hamilcar Barca, who had held his ground unconquered to the last moment in Sicily and who afterwards (in concert with Hanno the Great, the general of the aristocratic party) quelled the mutiny of the mercenaries, was burning with eagerness to take vengeance on Carthage’s autocratic and perfidious adversary. The power was in his hands and he was determined to use it to make every preparation for a fresh and decisive campaign. At the end of the year 237, immediately after the suppression of the mutiny, he proceeded on his own responsibility to Spain, and there conquered a new province for Carthage, larger than the possessions she had lost to Rome.

By allying himself with the popular party in Carthage, and giving his daughter in marriage to Hasdrubal, their leader, Barca gained a strong following in the capital; and even the dominant aristocracy, in spite of the suspicion with which they regarded the self-willed general—and not without good reason—could not but welcome gladly the revenues of the new province out of which they could defray the war indemnity to Rome. Hamilcar fell in 229; Hasdrubal, who took over his command, postponed the war against Rome and entered into an agreement with the latter, who was suspiciously watching developments in Spain, by which he pledged himself not[7] to cross the Ebro. This made it possible for Rome to bring the Celtic War to an end and conquer the valley of the Po while Hasdrubal was organising the government of Spain. But when, after the assassination of Hasdrubal in 221, his youthful brother-in-law, Hannibal, then twenty-four years of age, took over the command, he promptly revived his father’s projects.

In the year 219, by picking a quarrel with Saguntum, which had put itself under the protection of Rome, and attacking the city, which he took at the beginning of 218, he brought about a conflict which forced both Rome and the reluctant government of Carthage into hostilities. The declaration of war was brought to Carthage by a Roman embassy in the spring of 218. While Rome was making preparations for an attack on Spain and Africa simultaneously, Hannibal advanced by forced marches upon Italy by land, succeeded in evading the Roman army under Publius Scipio which had been landed at Massilia, and reached Italian soil before the beginning of winter. Rome was thereby foiled in her intention of taking the offensive. At the end of 218 and the beginning of 217 he had annihilated by a series of tremendous blows the Roman armies opposed to him, and, reinforced by hordes of Celts from the valley of the Po, had opened a way for himself into the heart of Italy.

Hannibal conceived of the war as a struggle against a state of overwhelming strength which by its mere existence made free action impossible for any other. He was perfectly well aware that he alone, with the army of twenty thousand seasoned veterans absolutely devoted to him, and the six thousand cavalry, which he had led into Italy, might defeat Rome in the field but could never overthrow her; in spite of any number of victories no attack on the capital could end otherwise than as the march of Pyrrhus on Latium had ended.

The Celts of the Po valley served to swell the ranks of his army but were of no consequence to the ultimate issue. Hannibal sacrificed them ruthlessly in every battle in order to save the flower of his troops for the decisive stroke. He made attempts again and again to break up the Italian confederacy, and after Cannæ, the greater part of the south of Italy, at least as far as Capua, went over to his side; but middle Italy, the heart of the country, stood by Rome with unfaltering loyalty. Carthage itself could do little, and its government would not do much; the Second Punic War is the war of Hannibal against Rome; Carthage took part in it only because and so far as she was ordered to do it. The fleets which Carthage sent against Italy could do nothing in face of Rome’s superiority at sea; no serious naval engagement was fought throughout the whole war.

A more conclusive result might perhaps have been arrived at if Hannibal had been able to keep open his communication with Spain, and if his brother Hasdrubal could have followed him immediately, so making it possible for them to sweep down upon Rome from both sides. It was a point of cardinal importance, and one which from the outset paved the way for the ultimate victory of Rome, that when the consul Publius Scipio found himself unable to overtake Hannibal on the Rhone in the August of 218, he hastened in person to Italy, where there were troops enough to set army after army in array against Hannibal; but by a stroke of genius he despatched his legions to Spain and thereby forced Hasdrubal to fight for the possession of that country instead of proceeding to Italy. By the time that Hasdrubal, having lost almost the whole of the peninsula to Publius Scipio the Younger, resolved in 207 to abandon the remainder of the Carthaginian possessions and march into Italy with his army, it was too late; he succumbed before the[8] Romans at the Metaurus. Complete success could only have been attained if Hannibal had succeeded in drawing the other states of the world into the war and carrying them with him in a decisive attack upon Rome.

The situation was in itself not unfavourable for such an undertaking. The Lagid empire, under the rule of Ptolemy II, surnamed Euergetes (247-221), had grown supine during that monarch’s latter years; the king felt his tenure of power secure and no longer thought it necessary to devote the same close attention to general politics or intervene with the same energy that his father had displayed. The fact that in the year 221 he left Cleomenes of Sparta to succumb in the struggle with Antigonus II of Macedonia and the Achæans, by withdrawing the subsidies which alone enabled him to keep his army together, is striking evidence of the ominous change which had taken place in the policy of the Lagidæ.

Ptolemy IV, surnamed Philopator, the son of Euergetes, was a monarch of the type of Louis XV, not destitute of ability but wholly abandoned to voluptuous living, who let matters go as they would. Accordingly in Asia the youthful Antiochus III, surnamed “the great” (221-187) was able to restore the ancient glories of the Seleucid empire, and although when he attacked Phœnicia and Palestine, he suffered a decisive defeat at Raphia in the year 217, Ptolemy IV made no attempt to reap the advantage of his victory. In Europe Philip V maintained his supremacy over Greece and kept the Achæans fast in the trammels of Macedonia.

Thus there was a very fair possibility that both kings might enter upon an alliance with Hannibal and a war with Rome. Philip V, a very able monarch, fully realised the importance of the crisis; we still have an edict dated 214, addressed by him to the city of Larissa, which shows that he rightly recognised the basis of Rome’s greatness, the liberality of her policy in the matter of civil rights and the continuous increase of national strength and territory which that policy rendered possible. But he could not extricate himself from the petty quarrels amidst which he had grown up; after a futile attempt to wrest their Illyrian possessions from the Romans he took no further part in the war, while Rome was able promptly to enter into an alliance with the Ætolians and Attalus of Pergamus and to take the offensive in Greece. Antiochus III, on the other hand, obviously failed altogether to grasp the political situation; to him the affairs of the west lay in the dim distance, and instead of taking action there he turned eastwards, to carry his arms once again to the Hindu Kush and the Indus.

The issue of the war was thus decided. From the moment when Rome determined not to give Hannibal a chance of another pitched battle but to confine herself to defensive measures and guerilla warfare, the latter could gain no further success. The fact that by this time he had won a great stretch of territory and was bound to defend it, hampered the mobility to which his successes had hitherto been due; the zenith of his victorious career was passed, he too was obliged to stand on the defensive, and could not avoid being steadily forced from one position after another. And now for the first time the vast strength of the Roman state stood forth in all its imposing majesty; for while defending itself against Hannibal in Italy it was able to take the offensive with absolute success in every other theatre of war, Spain, Sicily, and Greece.

How there arose on the Roman side a statesman and commander of genius in the person of Publius Scipio the Younger, who, after the conquest of Spain carried the war into Africa and there extorted peace, need not be recounted in this place. Rome had gained a complete victory, and with[9] it the dominion over the western half of the Mediterranean; thenceforth there was no power in the world that could oppose her successfully in anything she chose to undertake. The war of Hannibal against Rome is the climax of ancient history; if up to that time the development of the ancient world and of the Christian Teutonic nations of modern times have run substantially on parallel lines, here we come to the parting of the ways. In modern history every attempt made since the sixteenth century to establish the universal dominion of a single nation has come to naught; the several peoples have maintained their independence, and in the struggle political conglomerates have grown into states of distinct nationality, holding the full powers of their dominions at their own disposal to the same extent as was done by Rome only in antique times. On this balance of power among the various states and the nations of which they are composed, and upon the incessant rivalry in every department of politics and culture, which requires them at each crisis to strain every nerve to the utmost if they are to hold their own in the struggle, depends the modern condition of the world and the fact that the universal civilisation of modern times keeps its ground and (at present at least) advances steadily, while the leadership in the perpetual contest passes from nation to nation.

In ancient times, on the contrary, the attempt to establish a balance of power came to naught in the war of Hannibal; and from that time forward there is but one power of any account in the world, that of the Roman government, and for that very reason this moment marks first the stagnation, and then the decline, of culture. The ultimate result which grows out of this state of things in the course of the following centuries is a single vast civilised state in which all differences of nationality are abolished. But this involves the abolition of political rivalry and of the conditions vital to civilisation; the stimulus to advance, to outstrip competitors, is lacking; all that remains to be done is to keep what has already been gained, and, here as everywhere, that implies the decline and death of civilisation.

Rome herself, and with her the whole of Italy, was destined while endeavouring to secure the fruits of victory to experience to the full its disastrous consequences. She was dragged into a world-policy from which there was no escape, however much she might desire it; a return to the old Italian policy, with its circumscribed agrarian tendencies, had become impossible. Thus it comes about that the havoc wrought in Italy by the war of Hannibal has never been made good to this day, that the wounds it inflicted on the life of the nation have never been healed or obliterated. The state of Italy and the embryo Italian nation never came to perfection because the levelling universal empire of Rome sprang up and checked them.

There is no need to tell here how the preponderance of Rome made itself felt in political matters throughout the world immediately after the war with Hannibal, or how within little over thirty years all the states of the civilised world were subject to her sway. It is only necessary to point out that the ultimate result, the world-wide dominion of Rome, ensued inevitably from this preponderance of a single state, and was by no means consciously aimed at by Rome herself. All she desired was to shape the affairs of her neighbours as best consorted with her own interests and to obviate betimes the recurrence of such dangers as had menaced her in the case of Hannibal. Her ambition went no further; above all (though she kept Spain because there was no one to whom she could hand it over) she exhibited an anxious and well-grounded dread of conquests beyond sea. But she did not realise that by reducing all neighbouring states to helplessness[10] and impotence she deprived them of the faculty of exercising the proper functions of a state. Thenceforth they existed only by the good will of Rome; they found themselves constrained to appeal to Roman arbitration in every question, and involved Rome perpetually in fresh complications, while at the same time they felt most bitterly their dependence on the will of an alien and imperious power.

Thus Rome found herself at last under the necessity of putting an end to this state of things, first in one quarter and then in another, and undertaking the administration herself. In so doing she proceeded on no definite plan, but acted as chance or the occasion determined, letting other portions of her dominions get on as best they could, until matters had come to a crisis fraught with the utmost peril to Rome, and the only solution lay in a great war. For Rome, as for the world in general, it would have been far better if she had embarked on a career of systematic conquest.

Finally, let us briefly point out the effects of the policy of Rome on the development of civilisation. Rome and Italy assimilate more and more of the culture of Greece, and the latter, in its Latin garb, ultimately gains dominion over the entire West. Simultaneously, on the other hand, in the East a retrograde movement sets in. Rome strives by every means in her power to weaken the Seleucid empire, her perfidious policy foments every rebellion against it and places obstacles of all kinds in the way of its lawful sovereign. Thus, after a struggle of more than thirty years’ duration, all the East on the hither side of the Euphrates is lost to that empire. And although the Arsacid empire which succeeded it was neither nationalist nor hostile in principle to Hellenism, yet the mere fact that its centre was no longer on the Mediterranean but Babylonia, and that the connection of the Greek cities of the East with the mother-country was severed from that time forth, put an end to the spread of Hellenism and paved the way for the retrograde movement. It had already gained a firm footing in the Mediterranean; the support given by Antiochus IV, surnamed Epiphanes, to the Hellenising tendencies of certain Jews had driven the nationalist and religious party in Judea into revolt, and the disintegration of the empire by Roman intrigues gave them a fair field and enabled them to maintain their independent position. In the Lagid empire, about the same time, Ptolemy VII, surnamed Euergetes II, finally abandoned the old paths and the maxims of an earlier day, broke away from the Greeks, expelled the scholars of Alexandria, and sought to rely upon the Egyptian nationalist element among his subjects.

I shall not here trace beyond this point the broad outlines of the development of the ancient world. How the general situation reacted destructively upon the dominant nation; how the attempt to create afresh the farming class, which had been the backbone of Italy’s military prowess and consequently the foundation of her supremacy, resulted in the Roman revolution; how in that catastrophe, and the fearful convulsions that accompanied it, the embryo world-wide empire sought its appropriate form, and ultimately found in it the principate; and how the constitution was gradually transformed from a modified revival of the old Roman Republic to a denationalised and absolute universal monarchy—are all matters which must be left to another occasion for treatment.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Not to the earlier date of 366, as is commonly supposed. The decisive political conflicts out of which the later system of Roman government was evolved fall within the period of the wars of the Latins and Samnites and come to a final end with the Lex Hortensia, in the year 287.

THE SCOPE AND DEVELOPMENT OF EARLY ROMAN HISTORY

Written Specially for the Present Work

By DR. WILHELM SOLTAU

Professor of Ancient History in Zabern.

The early centuries of the history of Rome are closely bound up with the history of the rest of Italy. We must therefore briefly touch upon the development of the whole country.

About the middle of the second millennium B.C. certain Italic tribes made their way from the north into the Apennine peninsula, which up to that time had been inhabited first by an Iberian and then by a Ligurian race.

The settlement of the Balkan Peninsula was due, to a great extent, to successive immigrations of kindred tribes, who in most cases found a population of their own race in possession. In Italy it was not so. In the east we find the Messapians, a tribe akin to the Illyrians, settled for the most part in Apulia and Calabria. Tuscany and the valley of the Po received from the valleys of the Alps a population of Etruscans, a race whose origin and affinities are an enigma to students to this day. Their language is certainly not Indo-Germanic, their earliest settlements were the pile-dwellings of the Po valley, their later abode the natural fortresses of the Tuscan mountain peaks. Hence they cannot have come into the country by way of the sea. Nevertheless in Egyptian monuments of the thirteenth century B.C. we find mention of the auxiliary troops of the “Turisha.” They appear early to have won a certain reputation as pirates and soldiers in foreign service. Again, the Greeks believed that the Etruscans were akin to the Tyrrhenians of Asia Minor, and inscriptions in a language resembling Etruscan have been found in Lemnos, which seem to confirm this view. Whatever their origin, they represent a very ancient civilisation on Italian soil, and the Indo-Germanic tribes of Italy have been strongly influenced by them.

After the Etruscan immigration two other great tribes, this time of Aryan descent, pressed southward from the valley of the Po. Of these the first to come were probably the Siculi, a tribe which subsequently spread over Sicily and all the southwestern part of the mainland. The Ausonians[12] of Campania belonged to this race, as did the dwellers in the “lowland” south of the Tiber, i.e., in Latium.

The last to come was probably the Sabello-Umbrian race, which entered the country from the north by way of the Apennine valleys. For a long while it kept chiefly to the mountainous tracts of middle Italy, though some members of the tribe pushed forward, like advanced posts, to the west coast. The Umbrian settlement north of the Apennines was the only one which grew to large dimensions.

If we reflect that, besides these immigrations, a steady stream of Greek colonists had been occupying the coast of southern Italy ever since the eighth century B.C., their first settlements dating from two centuries earlier, and that, since the fifth century B.C. at latest, Gauls had been crossing the Alps to the valley of the Po, we can readily understand that Italy inevitably became the scene of violent conflicts. Yet she did not wholly miss the salutary effects of peaceful rivalry between the various racial elements. The population of southern Italy adopted the language, manners, and customs of the Greeks, and in the north the Etruscans served both as exponents of their own peculiar civilisation and as intermediaries between the Greeks and the mountain tribes.

Such were the conditions and influences under which Rome came into being. For centuries the Latins had fixed settlements in their mountain and woodland towns among the Alban Mountains. But the desire to secure themselves against Etruscan invasion on the one hand, and the growth of peaceful intercourse on the other, led them to found a colony on the Palatine “mount,” the last spur of a range of hills along the Tiber. The extremely advantageous situation of this new settlement led to the establishment of others in its vicinity, and ultimately to the conjunction which gave birth to the City of the Seven Hills. The Aventine and Cœlian hills did not as yet belong to it, but it included the Subura and the Velia, in addition to the Palatine mount, the Capitoline mount, the Esquiline mount, and the Quirinal and Viminal hills; and thus was even then one of the most considerable cities in Italy, with its fortified capitol, and its market-place or Forum between Mount Palatine and the “hill-town” (Collina) on the east. The colony soon threw Alba Longa, the mother-city, into the shade. Rome became the chief city of the Latin league. The capital of the confederate towns of Latium, the mistress of a small domain south of the lower Tiber, such is the aspect Rome bears when she emerges into history from the twilight of legend. The purity of the Latin language proves that she did not originate from a mixture of Latin, Sabine, and Etruscan elements as later inventions would have us believe. On the other hand there can be no question that Rome adopted many details of her civilisation and municipal organisation from her Sabine and Etruscan neighbours. A more important point is that she early received an influx of foreign immigrants, especially Tuscans, who in the capacity of handicraftsmen and masons, exercised a salutary influence upon the advance of civilisation among the Latin farmers.

Rome was at that time ruled by kings, assisted by a council of the elders of the city (the hundred senators). In important affairs they had to obtain the assent of the popular assembly (comitia curiata) which voted in thirty curiæ, according to the number of the thirty places of sacrifice in the city. For the rest, the kings had a tolerably free hand in the appointment of magistrates and priests.

From the legendary details of the history of the monarchy one thing only is clear, to wit, that in the sixth century B.C. Rome was ruled by monarchs[13] of Etruscan descent and was to some extent a dependency of the Etruscan rulers of the period.

In the seventh and sixth centuries B.C. the Etruscans had both vigorously repulsed the invasions of the Sabellians and taken the offensive on their own account. They had not only maintained and increased their dominion in the valley of the Po, but had established the Tuscan League of the Twelve Cities in Umbria, and thus put an end to Umbrian independence. At this time their sway extended southwards as far as Campania. A Tuscan stronghold (Tusculum) was built on the Alban hills. Etruscan sources of information, and first and foremost the pictures in Tuscan sepulchral chambers, leave no room to doubt that the Etruscan descent of the last three kings of Rome, the Tarquins and Servius Tullius, is a historic fact. Rome was therefore involved in the military operations of Etruscan commanders “Lucumones,” who fortified the city, adorned it with temples and useful buildings (among others the famous cloaca maxima, the first monument of vaulted architecture on Roman soil), and reorganised the army by the introduction of the Servian system of centuries, which afterwards became the foundation-stone of the Roman constitution. The whole body of the people was divided into four urban and sixteen rural recruiting districts (tribus), and all freeholders (assidui) were laid under the obligation of military service on the basis of a property qualification. Classes I to III served as heavy-armed soldiers, classes IV and V as light-armed. The whole number together constituted a body of 170 companies (170 × 100), divided into two legions on the active list and two in reserve, each 4200 strong, or 193 centuries inclusive of the centuries of mounted troops. From the establishment of the republic onwards this army was called together to elect consuls and vote upon laws under the title of the comitia centuriata.

The municipal comitia curiata ceased to be politically effective first under the military despotism of foreign rulers and then by reason of the expansion of the state till it included an area of nearly a thousand square kilometres. From that time forward the tribus became the basis of all political organisation, and remained so to the end.

But the army thus reorganised was a two-edged weapon. The tyrannical license of the last Tarquin roused the love of liberty in the breasts of the Romans. The army renounced its allegiance; through years of conflict and in sanguinary battles Rome, and all Latium with her, won back its independence of foreign Tuscan rulers.

The wars waged by Rome in the century after the expulsion of the kings are hardly worthy to be recorded on the roll of history. After valiantly repulsing the Etruscan commanders who endeavoured to restore Tarquin (496 B.C., battle of Lake Regillus), Rome entered into a permanent alliance with the Latin confederacy, an alliance that was not only strong enough to protect her against the constant attacks of mountain tribes (Æquians and Sabines on the northeast and Volscians on the southeast) but enabled her gradually to push forwards and conquer the south Etruscan cities of Veii and Fidenæ. Fidenæ fell in the year 428 B.C., Veii the emporium of southern Etruria, was reduced in 396, after a siege of ten years’ duration.

An attempt to intermeddle in the affairs of northern Etruria resulted in a catastrophe that threatened Rome with final annihilation. Some time earlier hordes of Gauls had penetrated into northern Italy through the passes of the Alps. At the beginning of the fourth century B.C. the Senonian Gauls effected a permanent settlement in the valley of the Po and from thence invaded Etruria. When they attacked Clusium (Chiusi) in middle Etruria[14] the Romans made an attempt at diplomatic intervention, but only succeeded in diverting the wrath of the enemy to themselves. The Gauls made a rapid advance, succeeded in routing the Roman forces at the little river Allia, only a few miles from Rome, and occupied the city itself. The citadel alone held out, but more than six months elapsed before the flood of barbarians subsided, and Rome was forced to purchase peace by humiliating concessions.

Rome arose after her fall with an energy that commands admiration, and she had soon won a position in middle Italy more important than that which she had held before the Gallic invasion. By partitioning southern Etruria among Roman citizens and founding colonies which at the same time served as fortresses and substantial bases for the advance of the Roman army she became a power of such consequence that she not only compelled the Æquians and Volscians by degrees to acknowledge her suzerainty but was able to assume the offensive in middle Etruria and the land of the Sabines.

When the Senonian Gauls returned to the attack, as they did two or three times a generation later (360, 349, and 330 B.C.), they found themselves confronted by the forces of the Latin league in such numbers that they declined to join issue in a pitched battle, presently retreated, and finally concluded a truce for thirty years (329-299 B.C.).

The increased strength of the Roman community within its own borders after the catastrophe of the Gauls is vouched for by the multiplication of municipal districts in spite of heavy losses in the field, the number and importance of the colonies, the gradual expansion of commerce and augmentation of the mercantile marine, the introduction of coined money (about 360 B.C.) in place of the clumsy bars of copper, and lastly, the increasingly active relations of Rome with foreign powers. About the year 360 B.C. the Romans sent votive offerings to Delphi, and made efforts both before and after to introduce Greek cults into their own country. But the strongest evidence of the extension of Roman trade and the esteem in which Rome was held as the contract-making capital of the commercial cities of middle Italy is furnished by her treaties with Carthage (probably 348 and 343 B.C.). The provisions (the text of which has come down to us) that Roman vessels should not sail westwards beyond a certain line in north Africa or in Spain, prove conclusively that the Carthaginians thought Italico-Roman competition a thing worth taking into account.

The internal development of the Roman state during this period (509-367 B.C.) is a matter of greater moment than many wars and military successes. The constitutional struggles which took place in an inland town in Italy are in themselves of small account in the history of the world. But the forms into which civil life and civil law were cast in Rome were subsequently (though in a much modified form) of great consequence to the whole Roman Empire. The division into curiæ obtained not only in Rome itself but in the remotest colonies of the empire in its day. The tribus, i.e., the districts occupied by Roman citizens enjoying full civil rights, afterward included all the citizens of the empire. Moreover, a particular interest attaches to the history of civil and private law among the Romans from the fact that its evolution has exercised a controlling influence on the juridical systems of the most diverse civilised peoples to this day.

The legal and constitutional changes which took place at Rome during this period were rendered imperatively necessary (in spite of the conservative character of the Roman people) by the changed status of the city. During the earlier half of the monarchy all civil institutions had been[15] arranged with an eye to municipal conditions. But the Rome of the Tarquins (in the sixth century B.C.) had hardly become the capital of a domain of nearly a thousand square kilometres before she found herself under the necessity of admitting her new citizens, first into the companies (centuriæ) of the army, and presently (after 509 B.C.) into the popular assemblies which voted by centuries. The old sacral ordinances, which were unsuited to any but municipal conditions, were superseded by the jus Quiritium, or Law of the Spearman, an ordinance of civil law.

It was no longer necessary to secure the assistance of the pontiff and the assent of the popular assembly voting by curiæ in order to make a will or regulate other points of family law. The civil testament and corresponding civil institutions took the place of the old system.

But the Roman state did not escape grievous internal troubles. After the expulsion of the kings the patrician aristocracy strove to get all power into their own hands. The senators were drawn exclusively from their ranks, civil and military office became the prerogative of a class. All priestly offices were occupied by members of patrician families. The patricians were supposed to be the only exponents of human and divine law. And it was an additional evil that the aristocratic comitia centuriata, which actually excluded the poorer citizens, were wholly deficient in initiative.

The Roman plebs suffered even more from the lack of legal security under an unwritten law arbitrarily administered by patrician judges than from the lack of political rights. In the famous bloodless revolution of 494 B.C. the plebs won the right of choosing guardians of their own, in the person of the tribunes of the people, who had the right of intervention even against the consuls, and soon gained a decisive influence in all public affairs. By decades of strife the hardy champions of civil liberty succeeded in securing first a written code of common law and then a share for the plebeians in public office and honours. From 443 B.C. onward there were special rating-officers (censors) independent of the consul, whose business it was to settle the place of individual citizens on the register of recruiting and citizenship, and to regulate taxation and public burdens.

But the most important triumph was that the assemblies of the plebs succeeded by degrees in securing official recognition for the resolutions they passed on legal, judicial, and political questions. After the year 287 B.C. the plebiscita had the same force as laws (leges) passed by the whole body of the people.

Although the subject classes had thus won a satisfactory measure of civil rights and liberties, they never forgot—and this is the most significant feature of the whole struggle for liberty—that none but a strong government and magistracy can successfully meet ordinary demands or rise to extraordinary emergencies. At Rome the individual magistrate found his liberty of action restrained in many ways by his colleagues and superiors. But within the scope of his jurisdiction, his provincia, he enjoyed a considerable amount of independence.

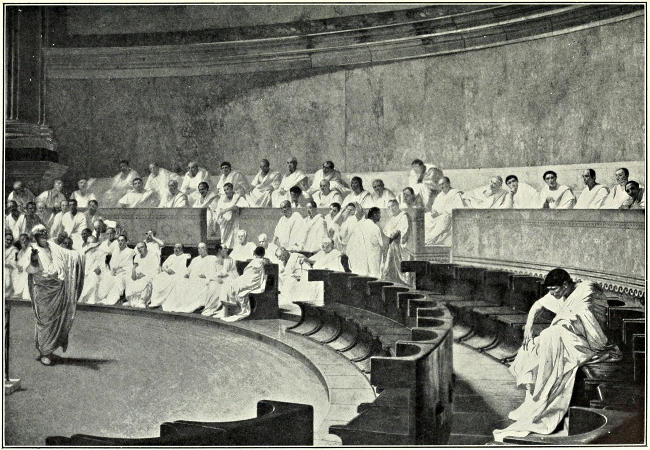

The senate was the only power which ultimately contrived to impose limits upon this independence. In that body the effective authority of the government was concentrated by gradual degrees. In face of the constant augmentation in the number of magistrates it frequently succeeded in getting its own way without much trouble. In the bosom of its members reposed the arcana imperii, the secrets of a policy which had known how to make Rome great. Selfishness, consistency, perfidy, perseverance—such were the motives, some noble, and some base, which shaped its resolutions.[16] Yet we cannot deny that there is a certain grandeur in the political aims represented by the senate. Nor did it fail of success; indeed, its achievements were marvellous.

In the year 390 B.C. the city of Rome was in the hands of the Gauls, and the Roman body politic had to all appearance perished. Exactly a hundred years later, at the end of the Second Samnite War, Rome was mistress of nearly the whole of Italy. A few years more, and she occupied Tarentum (272) and Rhegium (270). What is the explanation of this prodigious change?

It would be unjust not to assign its due share in the matter to the admirable temper of the Roman people. The self-sacrificing patriotism they invariably displayed, their stubborn endurance in perilous times, their manly readiness to hazard everything, even their very lives, if the welfare of the city so required—these qualities marked the Romans of that age, and they are capable of accomplishing great things. By them the admirable military system of Rome was first fitted for the great part it had to play in the history of the world, and became a weapon which never turned back before the most formidable of foes, and gave the assurance of lasting success.

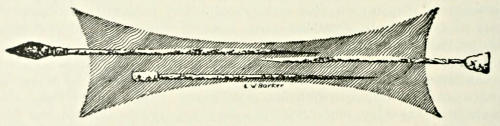

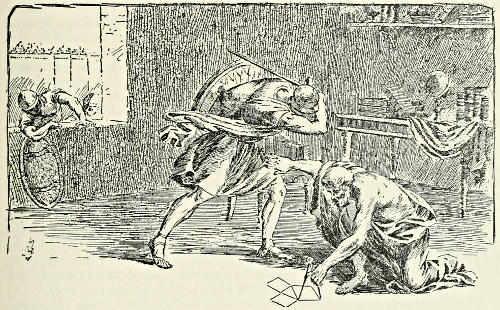

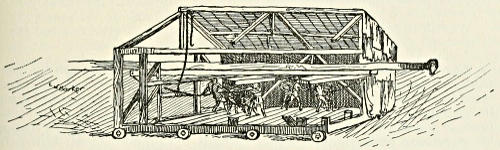

In process of time the ancient Servian phalanx had been superseded by an admirably organised and mobile disposition of the troops in maniples of 160 men each. Ranged in three files, with lateral spaces between, these bodies relieved one another during the fight, and thus were able to quell the most vehement onslaught of the enemy by constantly bringing forward fresh troops, which first hurled their long javelins and then charged with their short swords.

It became more and more the practice of the Roman state to extend to the lower classes the obligation of military service, which in all other parts of Italy was a privilege of the assidui or freeholders. Large numbers of landless men and freedmen were enrolled in the recruiting districts (tribus) in war times by the famous censor Appius Claudius Cæcus.

Opportune political changes favoured the development of Roman supremacy in Italy. The Etruscan dominion had fallen into utter decay during the course of the fifth century. Rome’s victorious struggle for liberty, the advance of the Samnites in southern Italy, and the immigration of the Gauls into northern Italy, had reduced Etruria to a second-class power. In the south the power of the wealthy Greek cities had been broken by Dionysius of Syracuse. Step by step Roman colonists made their way into lower Italy. Where the sword was of no avail Rome had recourse to road-making, the occupation and cultivation of waste land, and fresh settlements. Above all, the Latin colonies which she established in concert with the Latin league were of the utmost importance in securing the supremacy of Rome in middle Italy. These colonies served as fortresses, the colonists were a garrison always ready to stand on the defensive. The colonies themselves were established in such a way as to obstruct the coalition of the various races of Italy. They spread abroad Latin law and the Latin language among foreigners. They once more united the Romans and Latins in a common work of civilisation, after the two peoples had so hotly fought against each other in what is known as the Great Latin War (340-338 B.C.).

The skilful diplomatic negotiations and settlements by which Rome contrived either to gain over her former adversaries or reduce them to neutrality before she engaged in the struggle with the Samnites for the hegemony of Italy (342-340 and 326-304) are particularly worthy of note. She protected her rear by concluding armistices for many years with the Etruscans (351-311)[17] and Gauls (329-299). She entered into friendly relations with the Greek cities, and won over many communities in Campania and Lucania which had put themselves under the protection of the Samnites. Nay, she did not shrink from purchasing the friendship of Carthage by allowing her to take and plunder the seaboard cities of middle Italy which had revolted against Roman dominion. And she further displayed remarkable skill in securing her tenure of the possessions won in the Samnite wars. Only a small part of them was incorporated with Roman territory. Many cities received an accession of Latin colonists and so retained their municipal autonomy under new conditions. On the other hand the connection between the recalcitrant cantons of the Sabellian, Etruscan, and Middle Italian tribes was completely broken. Isolated and deprived of the right of intercourse (commercium) the various small cities and communities ceased to be of any importance either economically or politically.

The Romans had hardly completed the conquest of Etruria and the Samnite confederacy in the Third Samnite War (298-290 B.C.), and subjugated the kindred districts of Lucania and Bruttium when they found themselves involved in the struggles which then agitated the Greek world.

After 301 the several parts of the empire of Alexander the Great had become independent kingdoms. But the quarrels among the various diadochi went on and ultimately led to the expulsion of Demetrius Poliorcetes from Macedonia and the fall of Lysimachus of Thrace.

The unsettled state of these kingdoms inspired hordes of Gauls, athirst for plunder, with the idea of crossing the Alps and conquering both the Apennine and Balkan peninsulas. Italy owed her salvation to the vigorous defence made by the Romans at the Vadimonian Lake (283 B.C.); but Macedonia was occupied for several years and the swarms of Gauls spread as far as Delphi, and finally settled in Asia Minor under the name of Galatians.

Even before the Gallic invasion, Pyrrhus of Epirus, who had taken possession of Macedonia for a while, had withdrawn to his own home, and he and his army of mercenaries turned their eyes westward, eager for action. The wished-for opportunity of there regaining the influence and reputation he had lost in the west was not slow to present itself. Tarentum, the last independent city of any importance in Italy, had provoked Rome to hostilities and was endeavouring to enlist mercenaries for the war. Pyrrhus went to the help of the Tarentines, even as Alexander of Epirus, a cousin of Alexander the Great, had gone before him (334 B.C.). After some initial successes the latter had lost his life in battle against the Lucanians (331 B.C.). His nephew did not fare much better. The generalship of Roman mayors, elected afresh every year, was at first no match for that of Pyrrhus, who had great military successes to look back upon. Up to this time the Macedonian phalanx had invariably proved the instrument of victory, especially in the opening encounters of a campaign, and even the men of Rome gave ground before the elephants, the “heavy artillery” of the Epirots. But the second victory which the king gained over the Romans was a “Pyrrhic victory,” for his gains did not compensate his losses. On this occasion Rome owed the victory mainly to the inflexible courage of her statesmen. The blind Appius Claudius, who thirty years before had borne an honourable part in the successful struggle with the Samnites, caused himself to be led into the senate and by his arguments induced the Romans inflexibly to refuse all offers of peace on less than favourable terms. “Never have the Romans concluded peace with a victorious foe.” These proud words contain the secret of the ultimate success of Rome in all her wars of that century.

Fortunately for the Romans, at that very time the Greeks of Sicily urgently craved the aid of the king of Epirus. They had been defeated by the Carthaginians and their independence was menaced. Pyrrhus accordingly departed from Italy for more than two years, to gain some initial successes in Sicily and end in failure. When he returned to Italy it was too late. The Romans had established their dominion over the Italian rebels and were once more harassing Tarentum. Pyrrhus suffered a disastrous defeat at Beneventum in Samnium (275 B.C.), and Tarentum submitted soon after (272 B.C.). Pyrrhus himself was slain in Greece about the same time.

The subjugation of Italy was now complete. After Rhegium, the southernmost city in Italy, had been wrested from the hands of mutinous mercenaries (270 B.C.), Rome likewise took upon herself the economic administration of Italy by introducing a silver coinage (269 B.C.).

The war with Pyrrhus had clearly shown that Rome could not stop and rest content with the successes she had already gained, but would presently be forced into a struggle for all the countries about the Mediterranean, that is to say, for the dominion of the world as then known.

She contrived, it is true, very quickly to resume friendly relations with the Greek cities of Italy, whose sympathies had in some cases been on the other side in the war with Tarentum. The autonomous administration she allowed them to enjoy on condition of furnishing her with ships, and the protection which they, for their part, received from the leading power in Italy, could not but dispose them favourably to a continuance of her suzerainty.

With Carthage the case was different. Down to the time of the war with Pyrrhus the interests of Rome and Carthage had gone hand in hand to a great extent, or at worst had led to compromises in the three treaties of alliance (348, 343, and 306 B.C.). But in the wars against Pyrrhus it was in the interests of Carthage that Pyrrhus should be kept busy in Italy, while the Romans had contrived to turn his energies against the Carthaginians. And when the Romans were preparing to occupy Tarentum, a Carthaginian fleet hove in sight and manifested a desire to seize upon that city, the most important port of southern Italy. A power which had one foot in Rhegium, as Rome had, was bound presently to set the other down in Messana, and that would be a casus belli under any circumstances. How could the Carthaginians endure to see the island for the possession of which they had striven for two hundred years pass into the hands of the Romans?

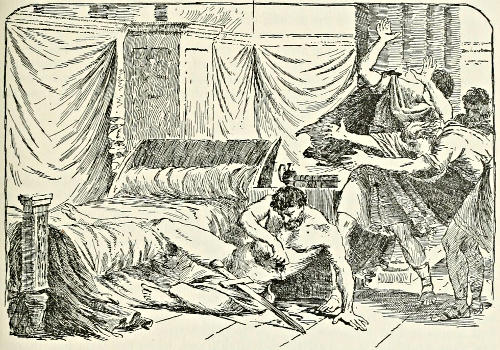

The actual pretext for the war is too dramatic to be passed over. The mutinous mercenaries of Agathocles (317-289 B.C.) had taken possession of the city of Messana. They were attacked by Hiero of Syracuse with such success that they appealed alternately to the Carthaginians and Romans for help. The Carthaginians came to the rescue first and put a garrison in the citadel of Messana. But the commander was so foolish as to enter into negotiations with the Roman legate, who had crossed the straits of Messana with a small body of troops, and in the course of them was taken prisoner—through his own perfidious treachery it must be acknowledged. Thus the key of Sicily fell into Roman hands, and war was declared. The history of the next hundred and twenty years is wholly occupied with the great struggle between these two cities, till at length, in 146 B.C., Carthage was laid level with the ground.