.

Demokrit, Epikur und Aristoteles über Atome

The task is, not so much to see what no one has yet seen; but to think what nobody has yet thought, about that which everybody sees.

Erwin Schrödinger (1887-1961)

It is scarcely an exaggeration to say that even in 1900 the only new idea to Leucippus's theory was that each chemical element was identified with a separate atomic species.

David Park, The How and the Why: An Essay on the Origins and Development of Physical Theory. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 1990.

Greek 10 Drachma Coin with Democritus of Abdera and the atom, before the EURO replaced the Drachma

By convention sweet, by convention bitter, by convention hot, by convention cold, by convention colour: but in reality atoms and void (kenon) Democritus

Leucippus and Democritus.

Democritus is said to have discovered the atoms, (a-tomos which is a Greek word for not divisible), around 430 BC. He was a student of Leucippus (and maybe Philolaus). Democritus and Leucippus are mentioned together as having discovered the atoms but we know very little about Leucippus. Some (Epicurus) saids that Leucippus did not exist and that this name was used by Democritus as a pseudonym. However this is very probably not true. The work The Great World System is considered to be a work of Leucippus in which the atoms and void are postulated. Although Democritus wrote many books almost nothing than a few Fragments survived and what we know are comments from Aristotle and others. How can Democritus and Leucippus discover atoms without being able to see atoms? Even at the times of Ludwig Boltzmann scientists did not believe that atoms exist. Boyle and Boltzmann and others believed this but there was no direct proof.

A similar problem we have with Planck's idea of the quantization of energy. How is it possible to derive a quantization from the continuous spectrum of the black body radiation?

Leucippus, however, and his disciple Democritus hold that the elements are the Full and the Void--calling the one "what is" and the other "what is not." Of these they identify the full or solid with "what is," and the void or rare with "what is not" (hence they hold that what is not is no less real than what is, because Void is as real as Body); and they say that these are the material causes of things. And just as those who make the underlying substance a unity generate all other things by means of its modifications, assuming rarity and density as first principles of these modifications, so these thinkers hold that the "differences" are the causes of everything else. These differences, they say, are three: shape, arrangement, and position; because they hold that what is differs only in contour, inter-contact, and inclination. (Of these contour means shape, inter-contact arrangement, and inclination position.) Thus, e.g., A differs from N in shape, AN from NA in arrangement, and Z from N in position. As for motion, whence and how it arises in things, they casually ignored this point, very much as the other thinkers did. Such, then, as I say, seems to be the extent of the inquiries which the earlier thinkers made into these two kinds of cause. Aristotle, Metaphysics [985b]

Aristotle tells that according to Leucippus and Democritus the differences we see in materials around us are due to atoms that differ in shape (ρυσμός , rhysmos) like the symbols A and N for example, due to the arrangement (διαθηγή , diathige) like the symbols AN and NA, and due to their position (or orientation)(τροπή , trope) such as Z and N (meaning that Z looks like a rotated N).

The pleasures derivable from scientific investigations, and the delight which inventions afford when we consider their effects, are such that I cannot help admiring the works of Democritus, on the nature of things, and his commentary, entitled Cheirotoniton, wherein he sealed with a ring, on red wax, the account of those experiments he had tried. Marcus Vitruvius Pollio, de Architectura

Maybe there are philosophical and mathematical reasons why Democritus assumed the existence of the atoms. For example dividing the matter into smaller and smaller parts leads to paradoxa such as described by Zeno. But there are also simple all day observations that could be used by Democritus. Take a glass filled with water. Water seems a continuous substance without holes. We do not have any evidence of empty space and atoms if we see the water in the glass. Democritus may have observed that when sugar is solved in the filled glass then sugar seems to disappear and even the volume seems not to change. So Democritus may have asked where has the sugar gone? There must bee empty space inside the water where the sugar went.

Another problem for Democritus is to explain how we can cut an apple with a knife. If the matter is continuous then we cannot explain this. There must be empty space between the constituents of the apple where the knife goes through. The knife moves atoms apart but in order to do this there must be empty space. Therefore Democritus concludes that the continuous objects around us are an illusion. “Only void and atoms exist”.

Democritus and Leucippus believed that growth was the joining of small particles to other particles, disassociation the opposite. Aristotle thought that this was a fairly accurate account of growth and death, for he discussed this topic when he stated his belief that Democritus examined the subjects in depth. He then goes on to discuss this view of growth with those of Plato that were espoused in The Timaeus.

Some consider that Democritus used logic arguments for the existence of atoms that if a object can be in principle divided in smaller and smaller parts then it is in principle an objective that is build by objects without magnitude? As Aristotle says:

Concerning there being atomic magnitudes. Democritus would appear to be convinced by appropriate, that is, physical arguments, ..., For there is a problem is someone would claim that a body, that is a magnitude, is divisible everywhere and this is possible, then it may be divided at the same time, even if it has not been divided at the same time. And if that were to happen, there would be nothing impossible. Thus, if it is of such kind as to be divisible everywhere - whether in the middle in the same way or in general, when it has been divided, nothing impossible will have happened, since even when it has been divided ten thousand times into ten thousand parts there is nothing impossible, although perhaps no-one would ever divide it so. As body, then, is such divisible everywhere, let it be divided. What will then be left? Magnitude? For that is not possible, for something will not be divided, whereas it was divisible everywhere. However, if there will not be any body or magnitude, and still there will be a division, whether it will consist of points, and there are sizeless things of which it is composed, or there will be nothing at all, so that it would come to be from nothing and be composed of nothing, and the whole would be nothing but appearance. Similarly if is consists of points, it will not be a quantity. For whenever they touched and there was one magnitude, and they were together, they did not make the whole any larger. For when divided into two or more, the whole is not anything smaller, nor larger, than before. There even if all points are put together they will not produce any magnitude.

Greek 100 Drachma note with Democritus and the atom, before the EURO replaced the Drachma

In the section On Generation and Corruption, Aristotle compares the theory of the Atomists that growth is the combination of small particles and void with that of Plato in which growth is the addition of planes (See this work from a Perseus Student Project), as Plato postulates in the Timaeus 55.a. While both theories postulate the existence of atomic magnitudes, Plato postulated the existence of planes instead of the small various shaped solid particles of the Atomists. Aristotle decided that Plato's theory was false and full of paradoxes. The main problem that Aristotle appeared to have with Plato's theory is the lack of any belief in the existence of the void; since, Aristotle said, in On Generation and Corruption, Book I.2, "Nothing except solids results from putting planes together: they do not even attempt to generate any quality from them."

The idea of atoms is also supported later by Epicurus (about atoms and void, περὶ ἀτόμων καὶ κενοῦ) who studies Democritus theory under Nausiphanes of Teos. His theory is (1) we see that there are bodies in motion, and (2) nothing comes into existence from what does not exist derived from the principle that for everything which occurs there is a reason or explanation for why it occurs, and why this way rather than that (the Principle of Sufficient Reason).

The motion implies that there must be empty space i.e. void. Epicurus thinks that macroscopic bodies that we see are are made up of smaller objects which again can are made from smaller objects. However this process of division cannot go on indefinitely, because otherwise bodies would dissolve away into nothing.

Peter Prevos discusses problems that have been considered by infinite small and partless atoms:

Aristotle argues in book VI of Physics atoms can not touch each other if they are considered to be sizeless. If they would touch each other ‘whole to whole’, the parts would eclipse each other. Sizeless atoms are also unable to touch ‘part to part’ or ‘part to whole’ because they have no parts. Minimal parts themselves are partless, which raises the question whether the theory of minimal parts only moves Aristotle’s problem about contact and succession to another level. Epicurus offers the analogy of perceptible minima as a solution. Epicurus proposes an object that is so far away that it can just be seen. When the object if moved further even the slightest, it would not be visible anymore.1 The minimum size the object appears to the observer is considered to be partless. The observer would not be able to see only part of the object as it would disappear from the field of view. Epicurus’ argument is that sensible minima must be next to one another just as our visual field can be conceived to be composed of perceptible minima. Epicurus argues that sensible minima and minimal parts of atoms are analogous and that the analogy explains how minimal parts can touch each other.

Then the question is how can a partless object such as an atom move.

The problem stated by Aristotle implies that partless objects either move incidentally to the movement of a larger body or—as described above—we can not state that it is ‘moving’ but only that it ‘has moved’. The latter implies, according to Aristotle, that time consists of a discontinuous succession of partless moments, which in turn implies that motion is staccato as the atom jumps in discrete sections of time and space.

Without accelerators just using philosophical arguments and observations such as cutting an apple with a knife Democritus probably “discovered” the atoms. It is possible to think that the atoms were discovered from philosophical first principles only. I think that there are also indirect observations as described before. Today similar problems exist. Theoretical physicists developed models which cannot be tested experimentally. They require accelerators as large as an entire galaxy to achieve the necessary energy. But from time to time some experimental physicists have some idea how experiments can be done that require only limited resources and that are accurate enough to test the theoretical models. The first of them seems to be Democritus.

In the first half of the first century BC

Titus Lucretius Carus

Titus Lucretius Carus (ca. 99/4-55 BC), writing in Latin, set forth the teachings of the Epicurean school in De rerum natura. There he held that "the soul is itself material and so closely associated with the body that whatever affects one affects the other. Consciousness ends with death. There is no immortality of the soul. The universe came into being through the working of natural laws in the combining of atoms" (Columbia Desk Encyclopedia 1975:1626). This view is supported by the force of the wind which is the result of the impact of innumerable atoms. Lucretius says in The Nature of Things that atomic nature all lies far below our powers of observation; hence since atoms cannot be seen, their movements, too, escape us.

According to Lucio Russo in La Rivoluzione Dimenticata (The Forgotten Revolution), Feltrinelli, Milan, 2001:

Science owes to the ancient atomists not just the generic concept and the name of ‘atom’,but also ideas like the chaotic motion of atoms (an idea which, developed in the Hellenistic period and rediscovered in the modern epoch, was essential to the birth of the kinetic theory of gases1 ), or the idea of the existence of atomic hooks which can link to each other2 : an image occasionally still used as a didactic illustration in chemistry texts.

1See for example Diogenes Laertius, Vitae philosophorum, IX, 3, where the idea is attributed to Leucippus. It would be interesting to know the origin of the conception of the chaotic motion of atoms. An remarkable step of Lucretius on the disordered motion of dusty particles illuminated by sunbeams gives an indication of the kind of phenomenology which could have suggested the idea. Lucretius points to the disordered and extremely rapid motion of the atoms as the ultimate cause of the motion, gradually slower, of particles of larger dimensions. It is interesting to compare the lucid explanation of Lucretius with the vitalist explanation given in 1828, apropos of an analogous phenomenon, by the famous discoverer of Brownian motion. (R. Brown, in “Philosophical Magazine”, 4, 1828),(R. Brown, Annalen der Physik und Chemie, 14, 1828)

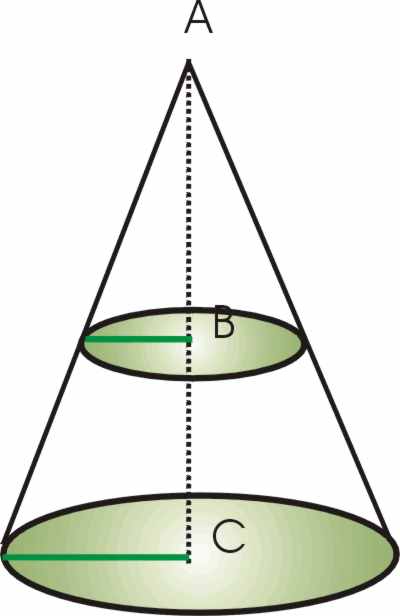

..εἰ κῶνος τέμνοιτο παρὰ τὴν βάσιν ἐπιπέδῳ, τί χρὴ διανοεῖσθαι τὰς τῶν τμημάτων ἐπιφανείας, ἴσας ἢ ἀνίσους γιγνομένας; ἄνισοι μὲν γὰρ οὖσαι τὸν κῶνον ἀνώμαλον παρέξουσι πολλὰς ἀποχαράξεις λαμβάνοντα βαθμοειδεῖς καὶ τραχύτητας, ἴσων δ' οὐσῶν ἴσα τμήματα ἔσται καὶ φανεῖται τὸ τοῦ κυλίνδρου πεπονθὼς ὁ κῶνος, ἐξ ἴσων συγκείμενος καὶ οὐκ ἀνίσων κύκλων, ὅπερ ἐστὶν ἀτοπώτατον. (Demokr.68B155) [Plut. de commun. not. 39 p. 1079 E ]

Whereas for physical objects Democritus considered the atoms to be necessary some say that his opinion was that for a mathematical object there should be no limitations in its divisibility. One of the mathematical problems he considered was the cone. If we slice a cone at a point B with a plane perpendicular to the axis then we obtain a circle. The cone is divided in two parts. What is is the area of the two circles of these two parts on both sides of the division? Does it change? If not then the area of the circle does not change along the cone axis and the cone is then a cylinder! Else if it is magnified it looks that it is not smooth and its width increases (in the Figure above if we approach C). Aristotle says that atoms have a skhema or a figure and there is a debate whether this means that they have also a finite size. The problem is that if something has a finite size then at least it seems that it is mathematical divisible if not physical. The word atomos means not divisible and it is not clear if this is a physical or mathematical property. If atoms have some shape is this possible without any size? Epicurus claims that atoms cannot have any magnitude. Alejandro Rivero discussed the question of the magnitude of atoms and its relation to the properties of atoms by Democritus: Rhythmos, Diathige and Trope in terms of modern differential geometry (

More than 2000 years were required to accept finally the idea of atoms. Even in 1897 Ernst Mach (1838-1916) with kinetic theory of gases theorist Ludwig Boltzmann present at the Imperial Academy of Sciences in Vienna loudly announced: “I don’t believe atoms exist!” 4

Quotes

"Epicurus attempted to deal with the contradiction between atoms falling through the void in parallel paths at the same speed and the appearance of novel combinations, or matter, by supposing very slight, chance deviations, or 'clinamen,' in an atom's path. He saw this as analogous to the question of human freedom in a determined nature; i.e., there is no room for ethical considerations. Indeed, "Epicureans saw the development of the world as a random, one-way process" (Toulmin and Goodfield 1965).

References

Peter Prevos, HELLENISTIC PHILOSOPHY Problems of Atomic Motion in Epicurean Philosophy.

1A.A. Long and D.N. Sedley, The Hellenistic philosophers, Volume 1, (Cambridge University Press, 1987), pp. 37–38.

2The existence of atoms with hooks had been affirmed by Democritus, as we know from the (lost) book of Aristotle On Democritus, a passage of which is reported by Simplicius (In Aristotelis De caelo commentaria)

3Democritus in H. Diels, Die Fragmente der Vorsokratiker, Berlin 1903; VI edition, Kranz Walther ed., Berlin 1951-1952, 3 vols.; reprinted Zürich 1996.

4Lindley, D. 2001. Boltzmann’s Atom: The Great Debate That Launched a Revolution in Physics, The Free Press, New York.

Physics by Aristotle, translated by R. P. Hardie and R. K. Gaye

On the Difference Between the Democritean and Epicurean Philosophy of Nature -- Karl Marx's doctoral dissertation, 1841 (http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1841/dr-theses/index.htm)

How Is the Universe Built? Grain by Grain. The New York Times

Leucippus

Epicurus: Lettter to Herodotus (a summary of his atomic theory)

RALPH E. KENYON JR. Atomism and Infinite Divisibility

Lucretius: De Rerum Naturae , About Lucretius

LUCRETIUS

Lucretius: BOOK II: MOVEMENTS AND SHAPES OF ATOMS , Translation of Lucretius by R. E. Latham

| Ancient Greece

Science, Technology , Medicine , Warfare, , Biographies , Life , Cities/Places/Maps , Arts , Literature , Philosophy ,Olympics, Mythology , History , Images Medieval Greece / Byzantine Empire Science, Technology, Arts, , Warfare , Literature, Biographies, Icons, History Modern Greece Cities, Islands, Regions, Fauna/Flora ,Biographies , History , Warfare, Science/Technology, Literature, Music , Arts , Film/Actors , Sport , Fashion --- |