.

THE

BIRDS OF AUSTRALIA.

LIST OF PLATES.

VOLUME V.

| Cacatua galerita | Crested Cockatoo | 1 |

| —— Leadbeateri | Leadbeater’s Cockatoo | 2 |

| —— sanguinea, Gould | Blood-stained Cockatoo | 3 |

| —— Eos | Rose-breasted Cockatoo | 4 |

| Licmetis nasicus | Long-billed Cockatoo | 5 |

| Nestor productus, Gould | Philip Island Parrot | 6 |

| Calyptorhynchus Banksii | Banksian Cockatoo | 7 |

| —— macrorhynchus, Gould | Great-billed Black Cockatoo | 8 |

| —— naso, Gould | Western Black Cockatoo | 9 |

| —— Leachii | Leach’s Cockatoo | 10 |

| —— funereus | Funereal Cockatoo | 11 |

| —— xanthonotus, Gould | Yellow-eared Black Cockatoo | 12 |

| —— Baudinii, Vig. | Baudin’s Cockatoo | 13 |

| Callocephalon galeatum | Gang-gang Cockatoo | 14 |

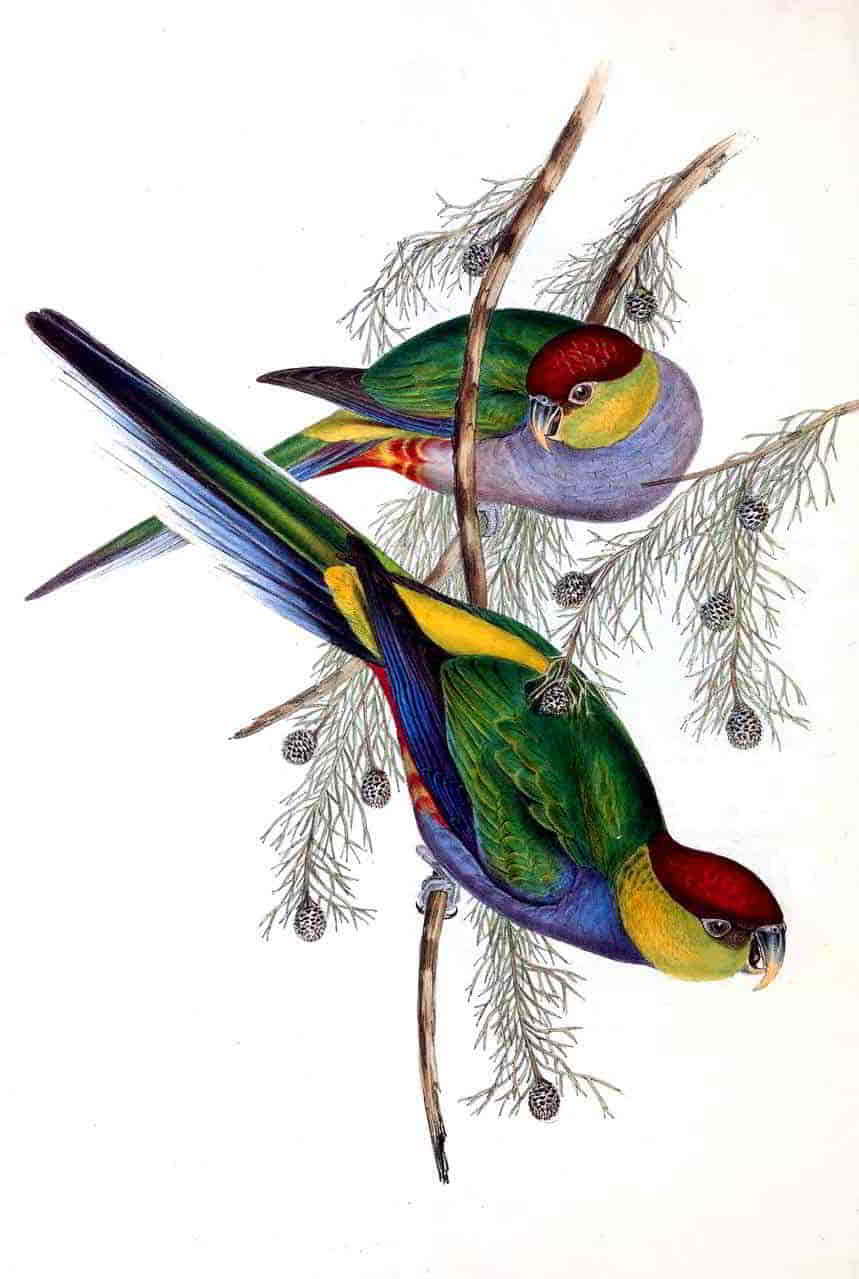

| Polytelis Barrabandi | Barraband’s Parrakeet | 15 |

| —— melanura | Black-tailed Parrakeet | 16 |

| Aprosmictus scapulatus | King Lory | 17 |

| —— erythropterus | Red-winged Lory | 18 |

| Platycercus semitorquatus | Yellow-collared Parrakeet | 19 |

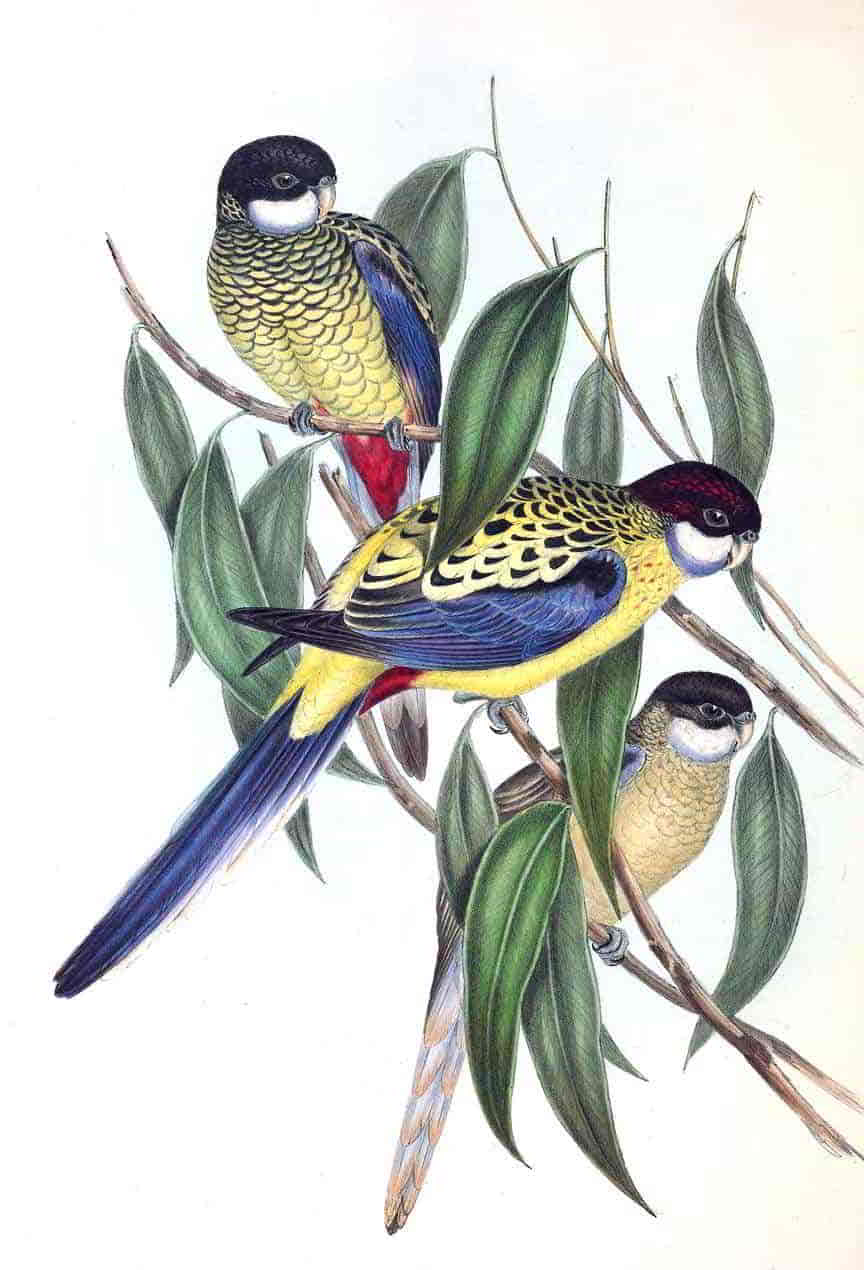

| —— Baueri | Bauer’s Parrakeet | 20 |

| —— Barnardi, Vig. & Horsf. | Barnard’s Parrakeet | 21 |

| —— Adelaidiæ, Gould | Adelaide Parrakeet | 22 |

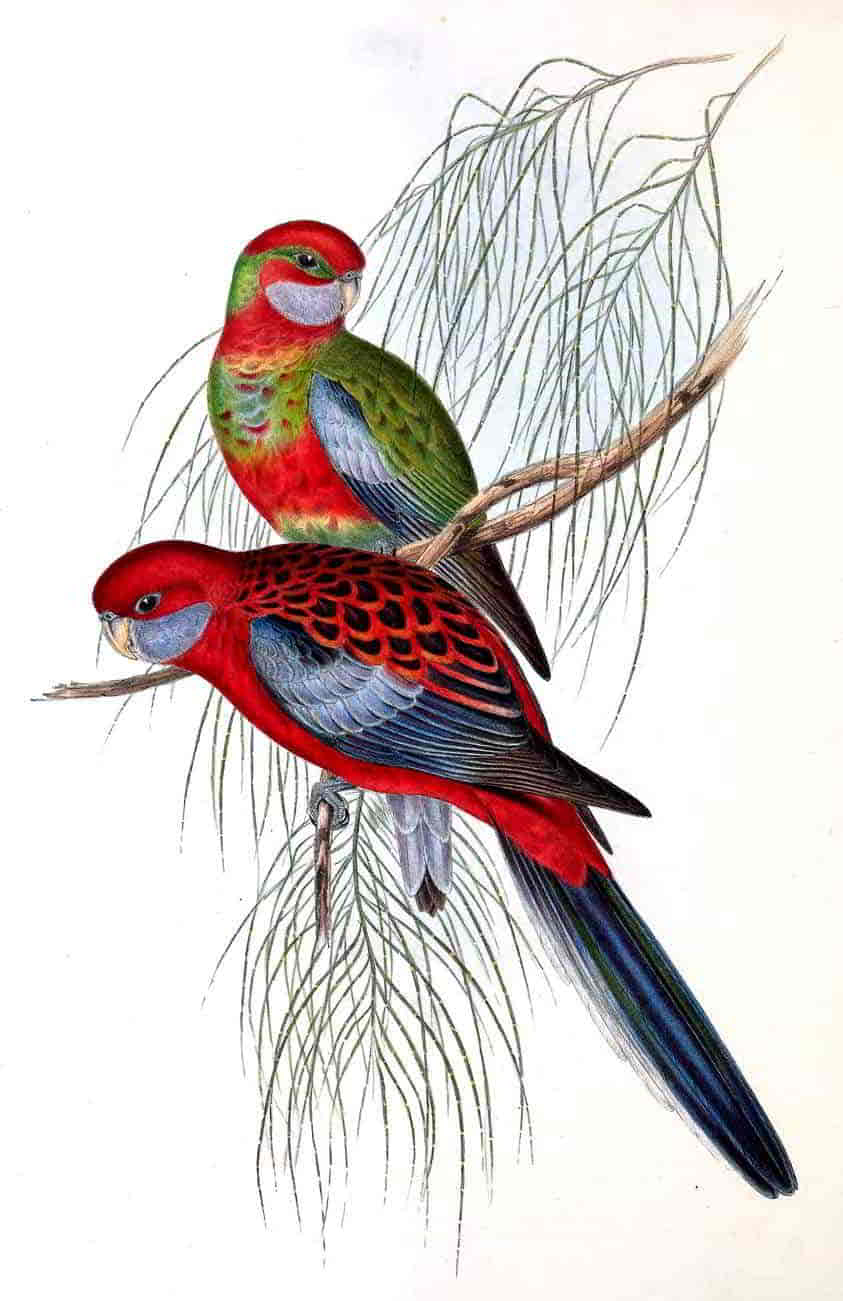

| —— Pennantii | Pennant’s Parrakeet | 23 |

| —— flaviventris | Yellow-bellied Parrakeet | 24 |

| —— flaveolus, Gould | Yellow-rumped Parrakeet | 25 |

| —— palliceps, Vig. | Pale-headed Parrakeet | 26 |

| —— eximius | Rose-hill Parrakeet | 27 |

| —— splendidus, Gould | Splendid Parrakeet | 28 |

| —— icterotis | The Earl of Derby’s Parrakeet | 29 |

| —— ignitus, Lead. | Fiery Parrakeet | 30 |

| —— Brownii | Brown’s Parrakeet | 31 |

| —— pileatus, Vig. | Red-capped Parrakeet | 32 |

| Psephotus hæmatogaster, Gould | Crimson-bellied Parrakeet | 33 |

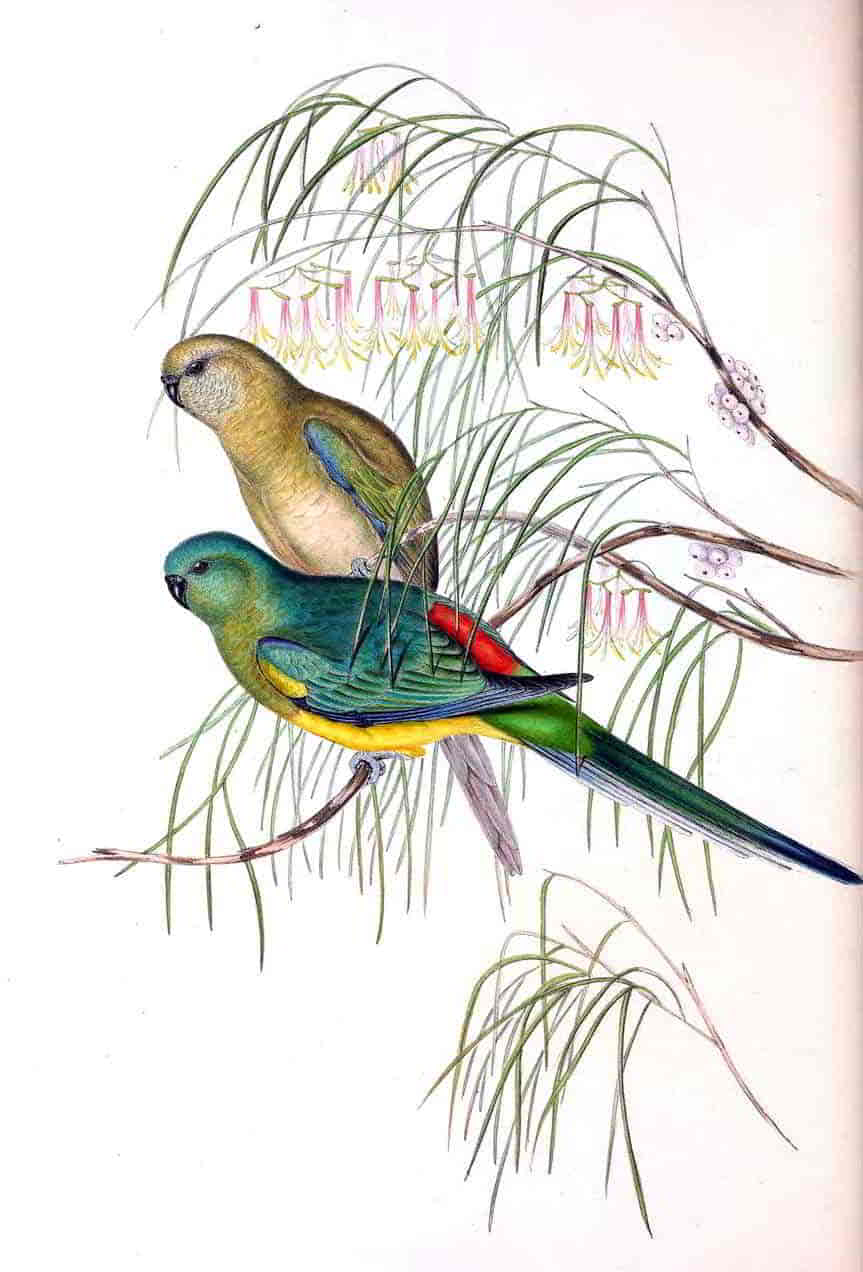

| —— pulcherrimus, Gould | Beautiful Parrakeet | 34 |

| —— multicolor | Many-coloured Parrakeet | 35 |

| —— hæmatonotus, Gould | Red-backed Parrakeet | 36 |

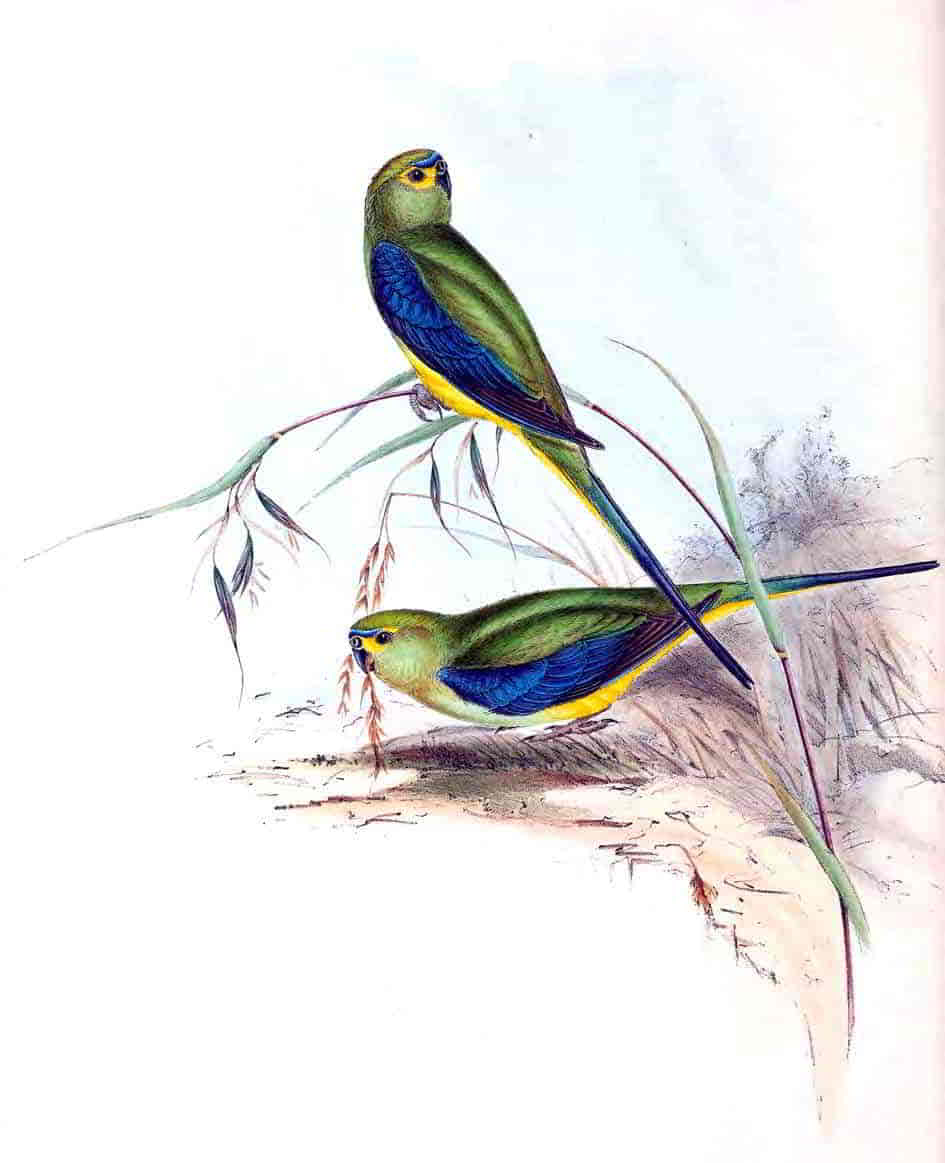

| Euphema chrysostoma | Blue-banded Grass-Parrakeet | 37 |

| —— elegans, Gould | Elegant Grass-Parrakeet | 38 |

| —— aurantia, Gould | Orange-bellied Grass-Parrakeet | 39 |

| —— petrophila, Gould | Rock Grass-Parrakeet | 40 |

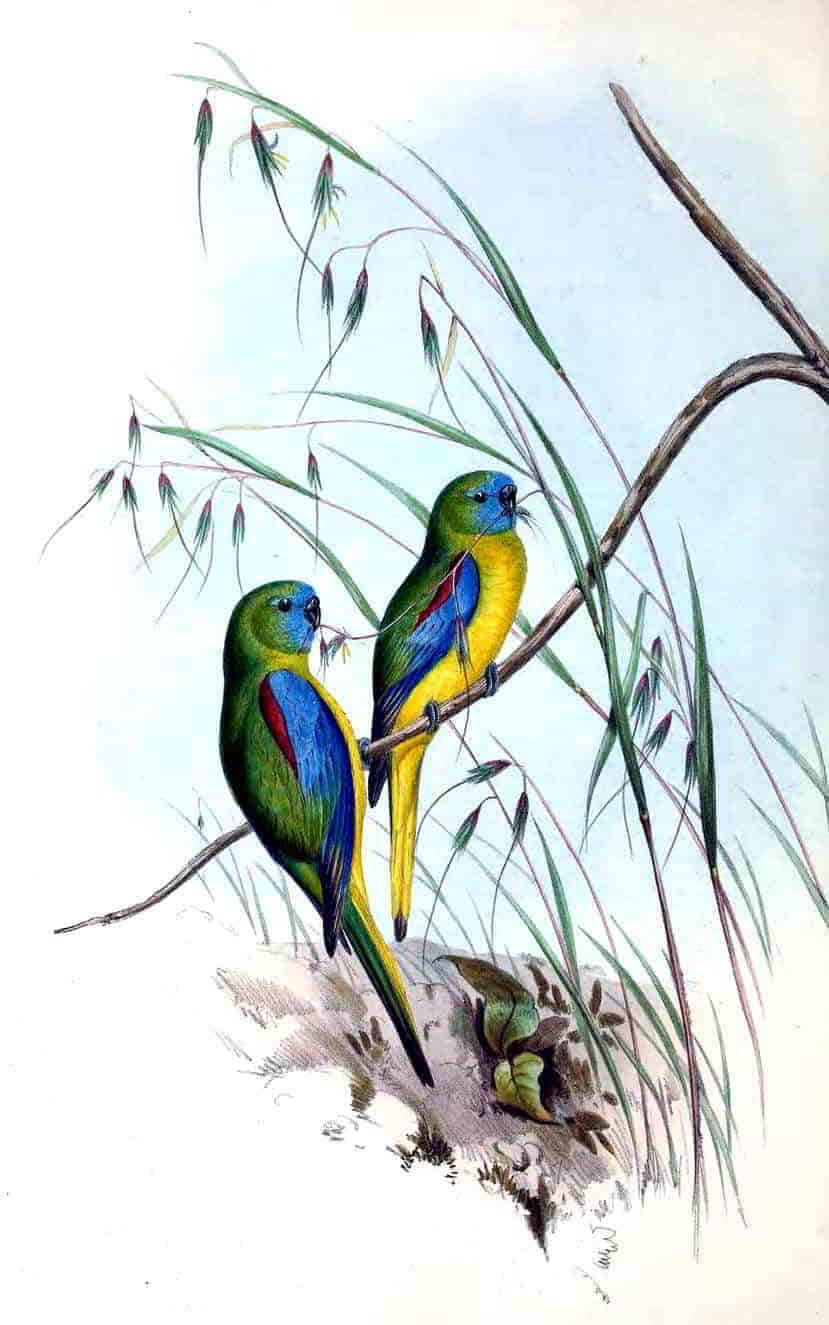

| —— pulchella | Chestnut-shouldered Grass-Parrakeet | 41 |

| —— splendida, Gould | Splendid Grass-Parrakeet | 42 |

| —— Bourkii | Bourke’s Grass-Parrakeet | 43 |

| Melopsittacus undulatus | Warbling Grass-Parrakeet | 44 |

| Nymphicus Novæ-Hollandiæ | Cockatoo Parrakeet | 45 |

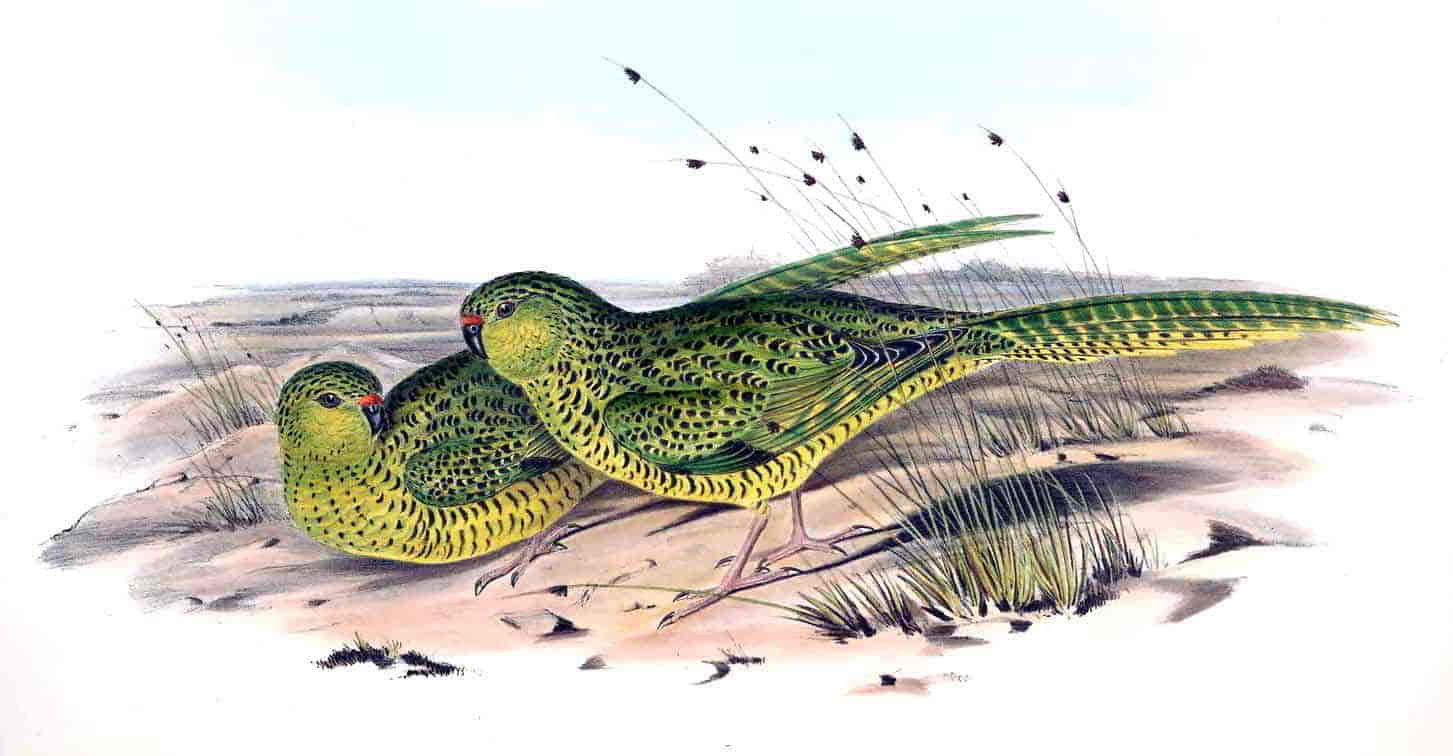

| Pezoporus formosus | Ground Parrakeet | 46 |

| Lathamus discolor | Swift Lorikeet | 47 |

| Trichoglossus Swainsonii, Jard. & Selby. | Swainson’s Lorikeet | 48 |

| —— rubritorquis, Vig. & Horsf. | Red-collared Lorikeet | 49 |

| Trichoglossus chlorolepidotus | Scaly-breasted Lorikeet | 50 |

| —— versicolor, Vig. | Varied Lorikeet | 51 |

| —— concinnus | Musky Lorikeet | 52 |

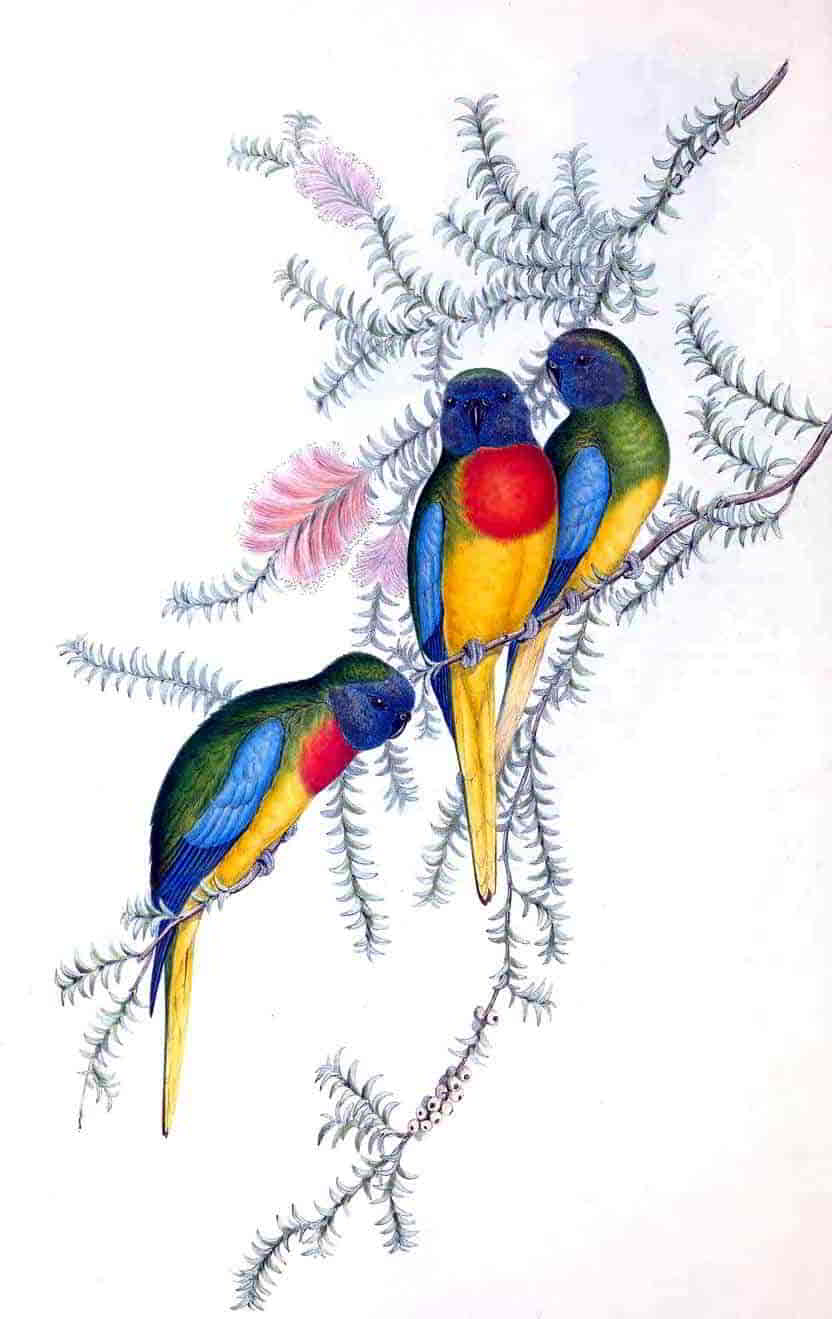

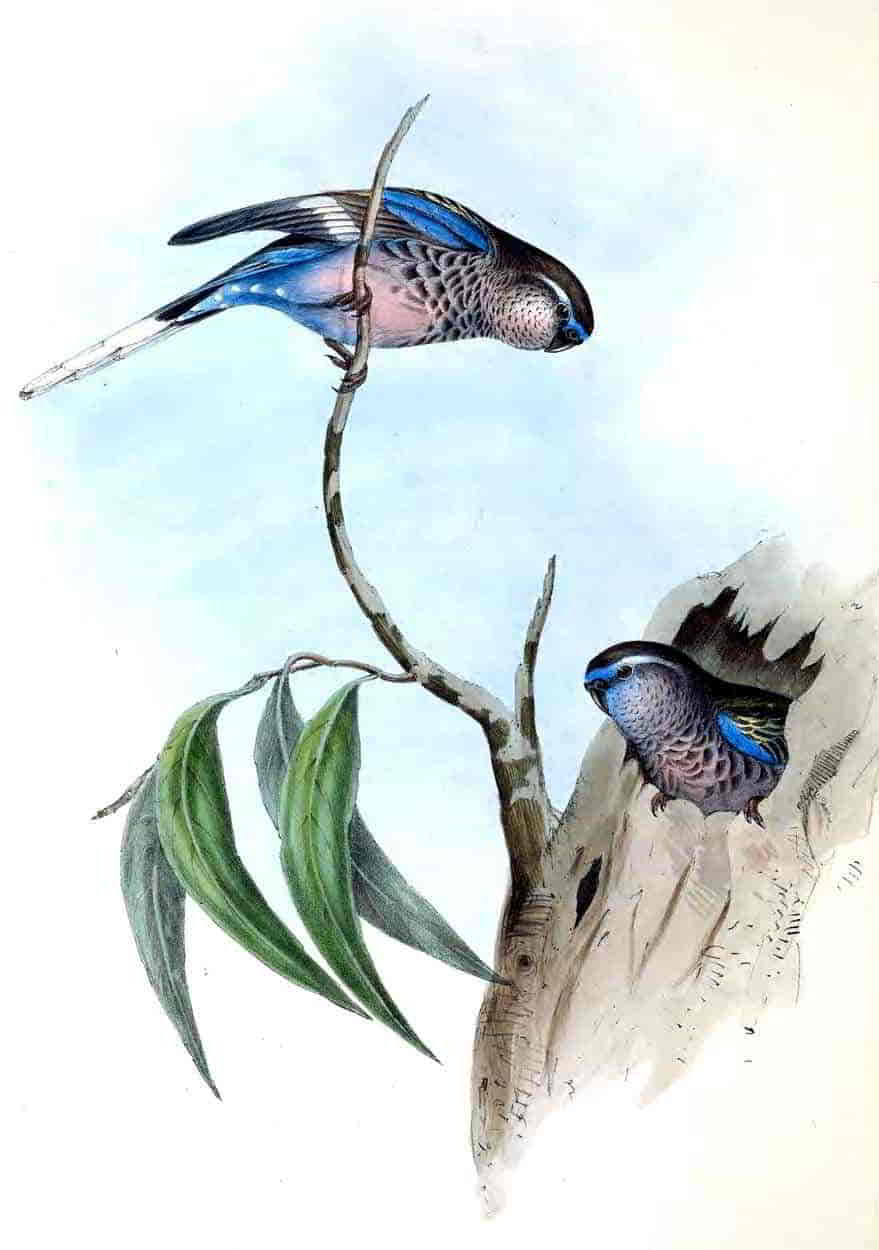

| —— porphyrocephalus, Diet. | Porphyry-crowned Lorikeet | 53 |

| —— pusillus | Little Lorikeet | 54 |

| Ptilinopus Swainsonii, Gould | Swainson’s Fruit Pigeon | 55 |

| —— Ewingii, Gould | Ewing’s Fruit Pigeon | 56 |

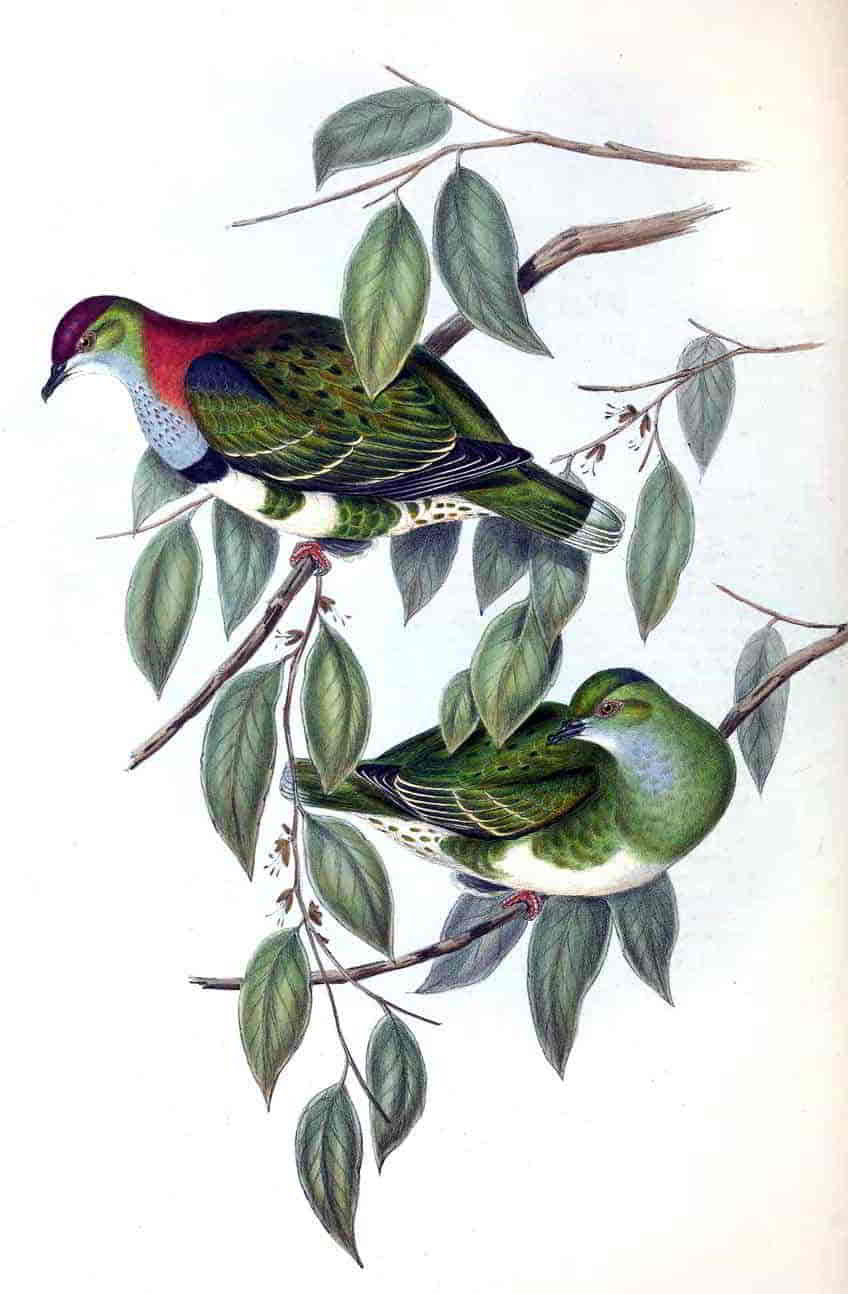

| —— superbus | Superb Fruit Pigeon | 57 |

| Carpophaga magnifica | Magnificent Fruit Pigeon | 58 |

| —— leucomela | White-headed Fruit Pigeon | 59 |

| —— luctuosa | Torres Strait Fruit Pigeon | 60 |

| Lopholaimus Antarcticus | Top-Knot Pigeon | 61 |

| Chalcophaps chrysochlora | Little Green Pigeon | 62 |

| Leucosarcia picata | Wonga-wonga Pigeon | 63 |

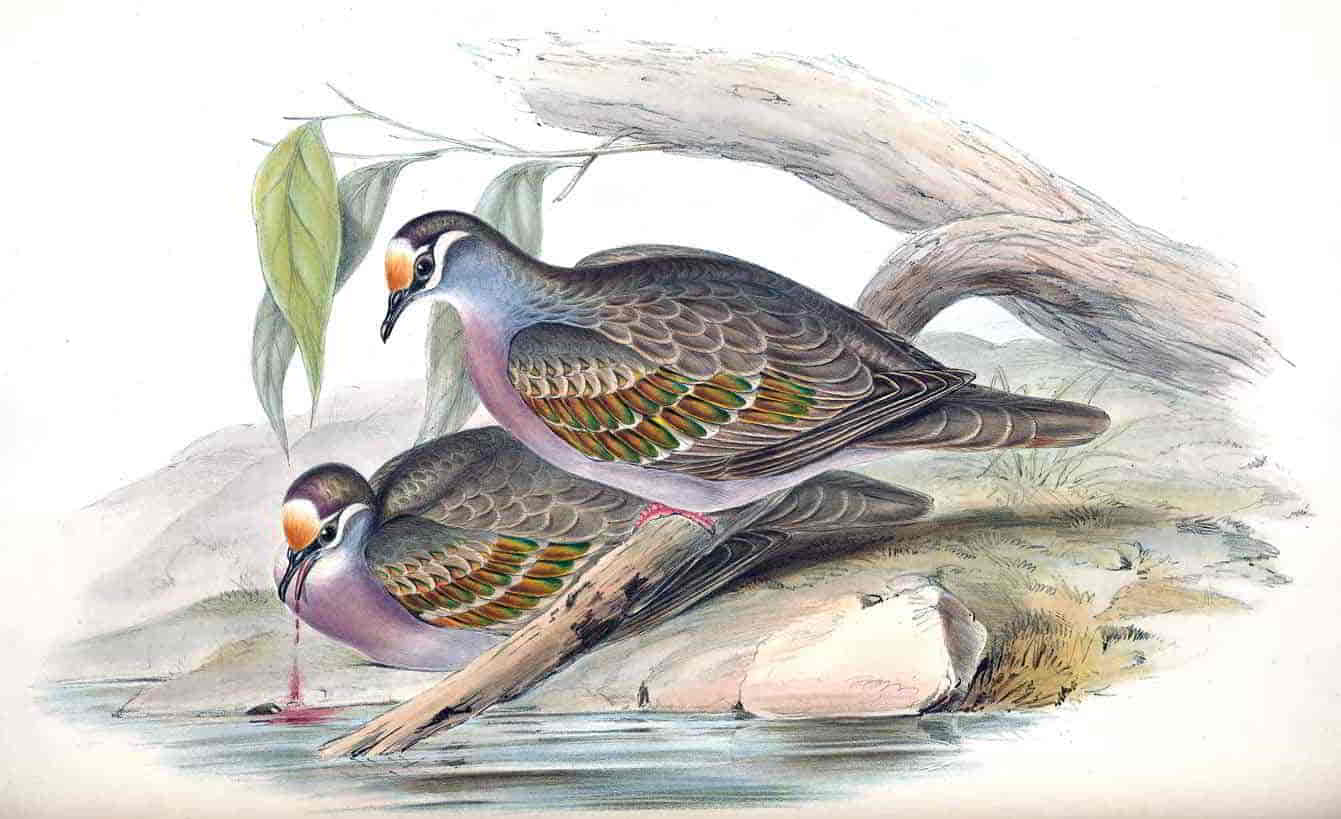

| Peristera[1] chalcoptera | Bronze-winged Pigeon | 64 |

| —— elegans | Brush Bronze-winged Pigeon | 65 |

| —— histrionica, Gould | Harlequin Bronzewing | 66 |

| Geophaps scripta | Partridge Bronze-wing | 67 |

| —— Smithii | Smith’s Partridge Bronze-wing | 68 |

| —— plumifera, Gould | Plumed Partridge Bronze-wing | 69 |

| Ocyphaps Lophotes | Crested Pigeon | 70 |

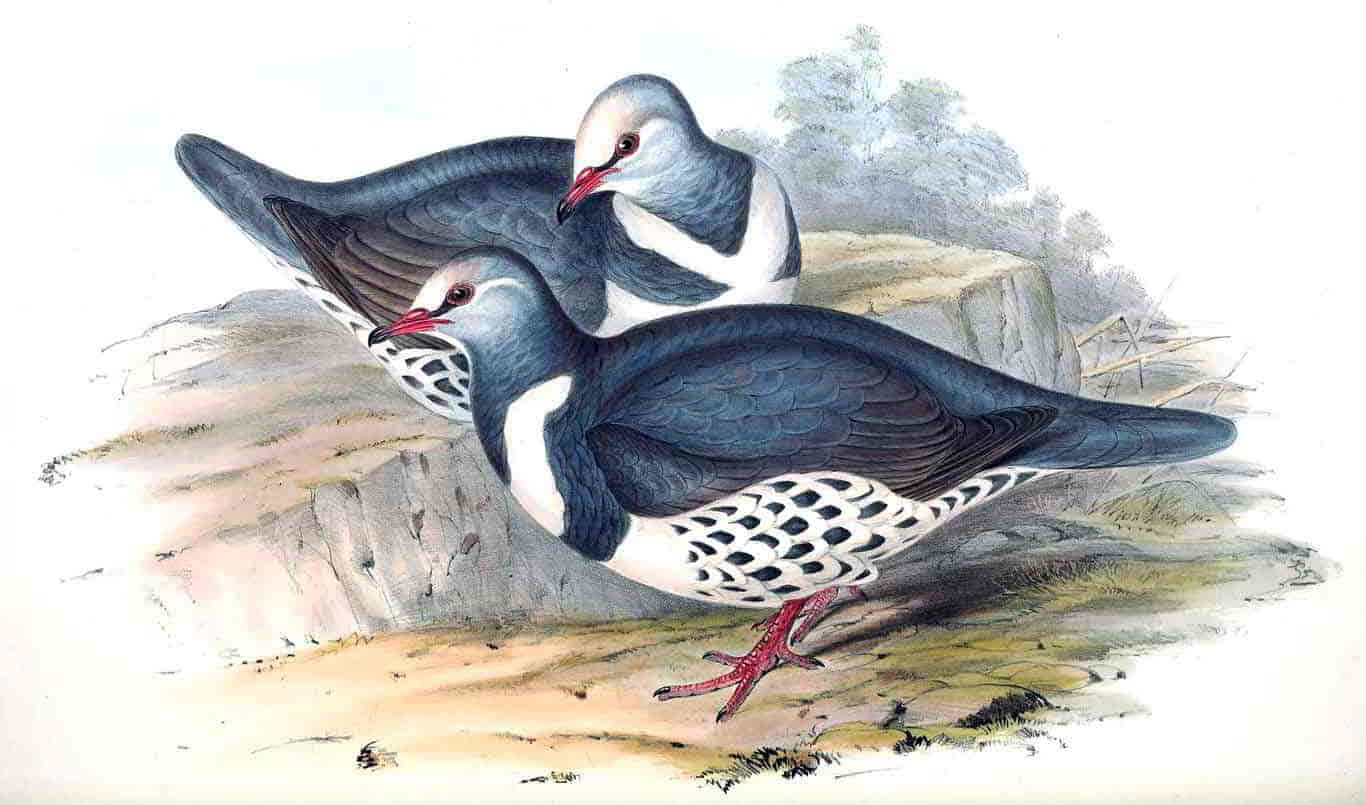

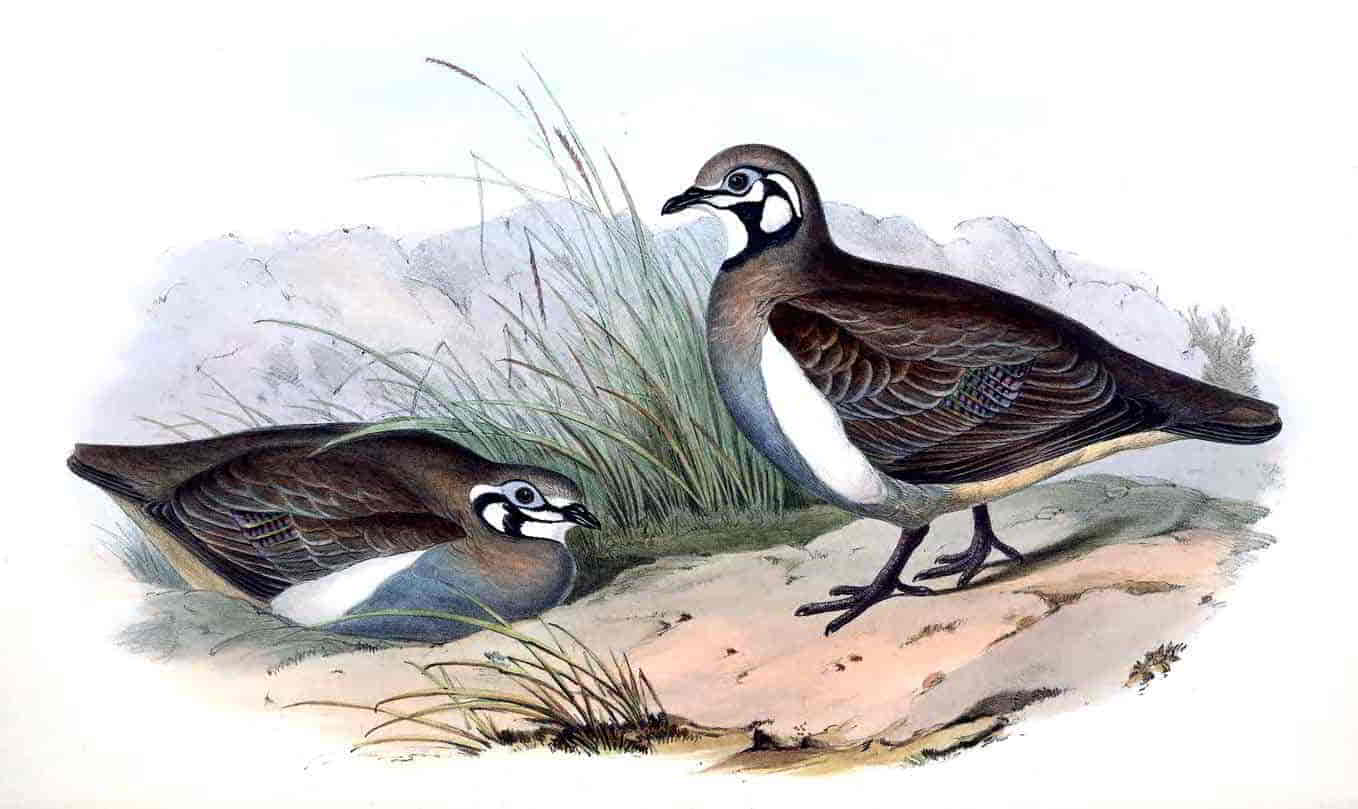

| Petrophassa albipennis, Gould | White-quilled Rock Dove | 71 |

| Geopelia humeralis | Barred-shouldered Ground Dove | 72 |

| —— tranquilla, Gould | Peaceful Ground Dove | 73 |

| —— cuneata | Graceful Ground Dove | 74 |

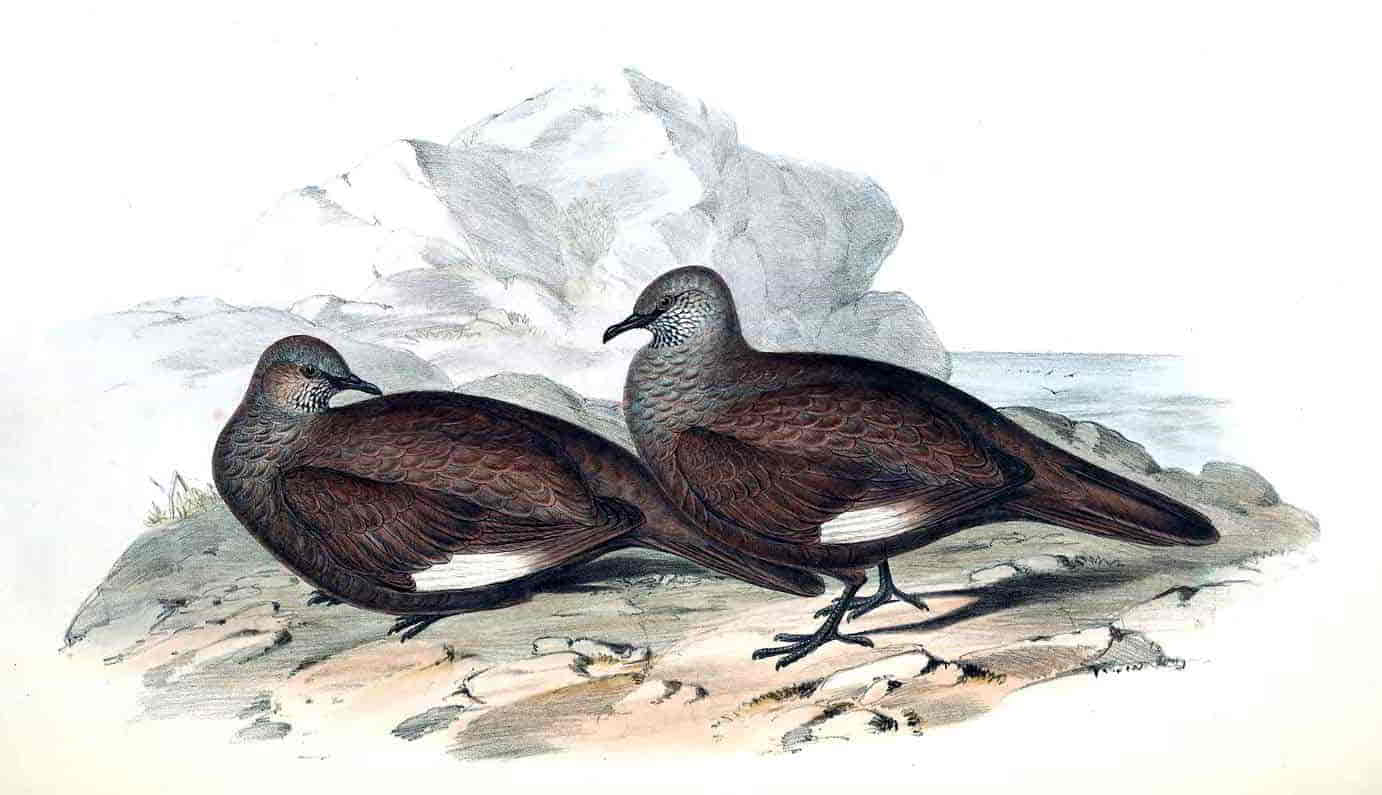

| Macropygia Phasianella | Pheasant-tailed Pigeon | 75 |

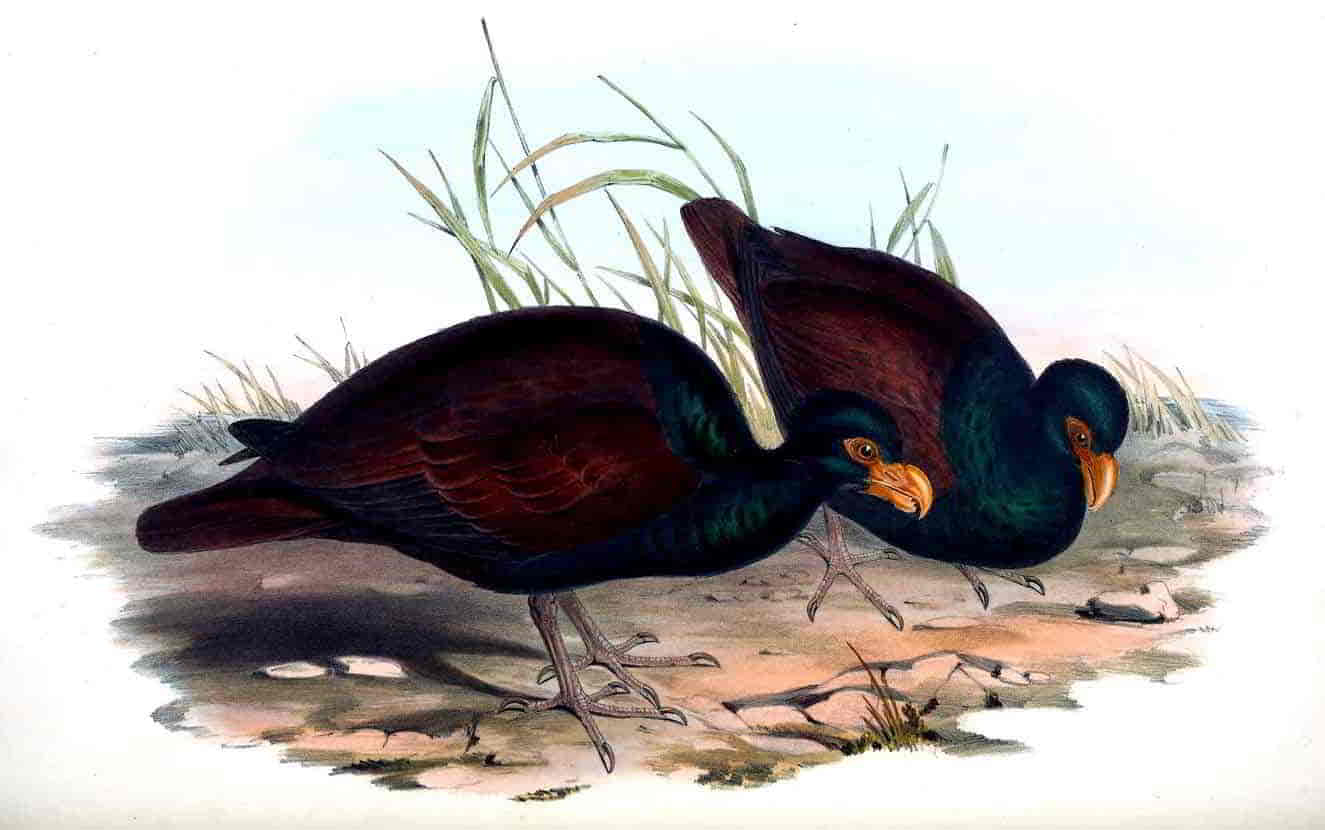

| Gnathodon strigirostris, Jard. | Gnathodon | 76 |

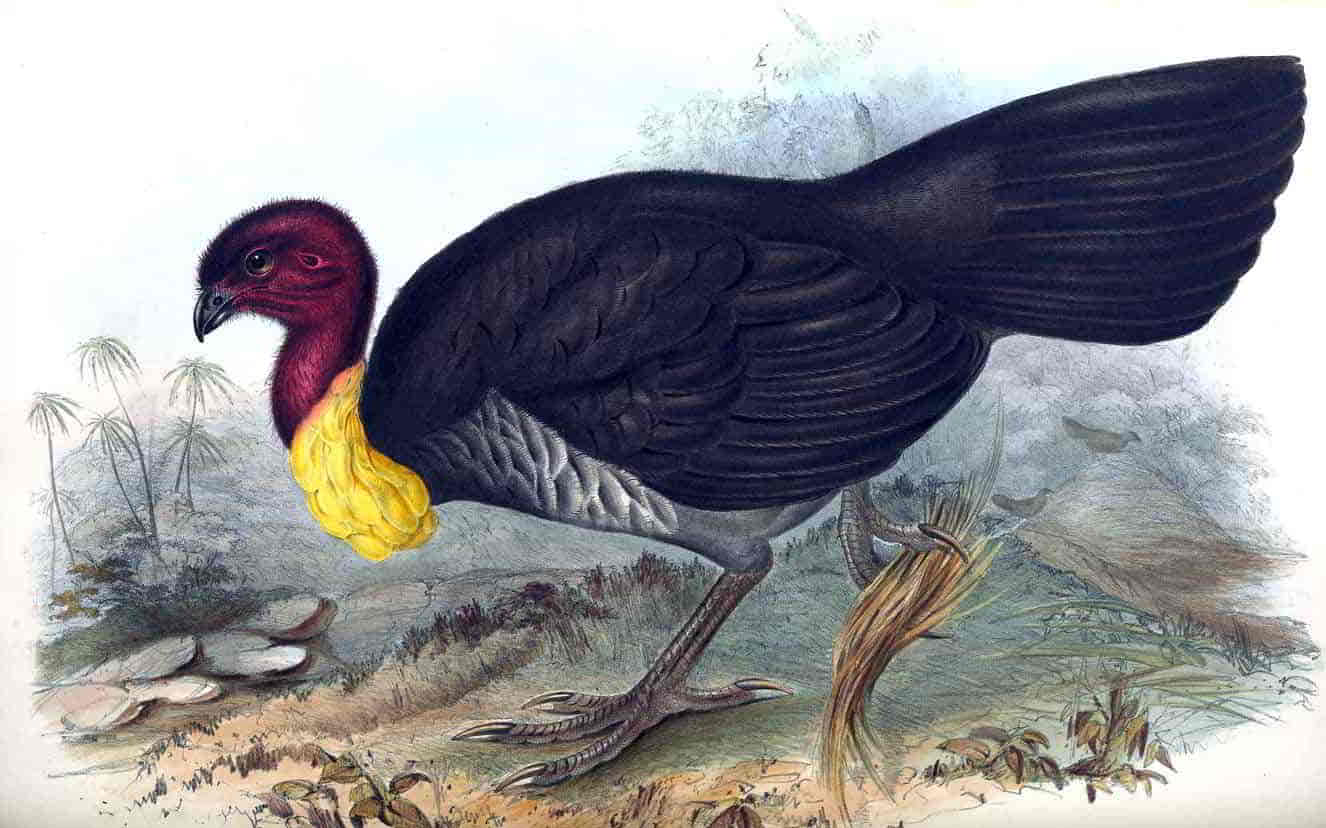

| Talegalla Lathami | Wattled Talegalla | 77 |

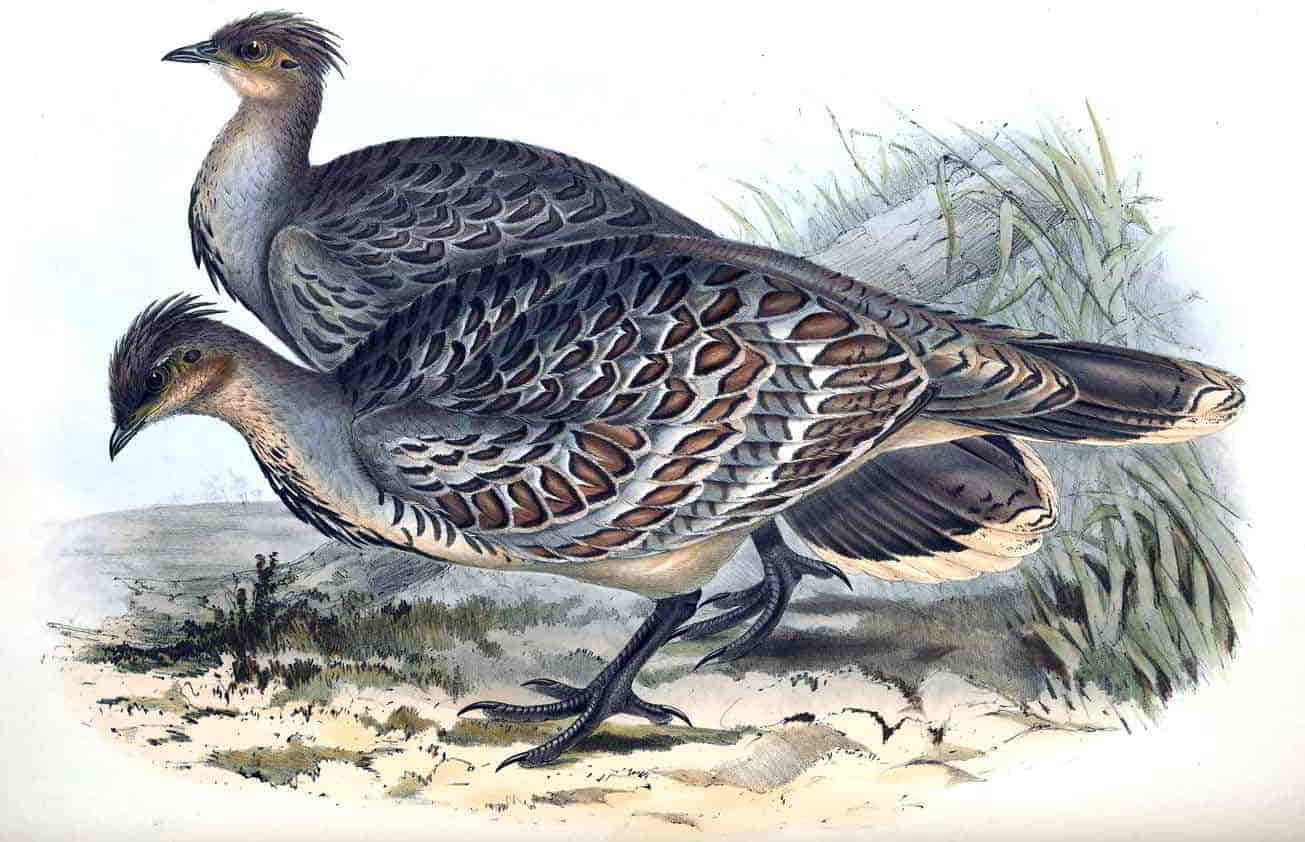

| Leipoa ocellata, Gould | Ocellated Leipoa | 78 |

| Megapodius Tumulus, Gould | Mound-raising Megapode | 79 |

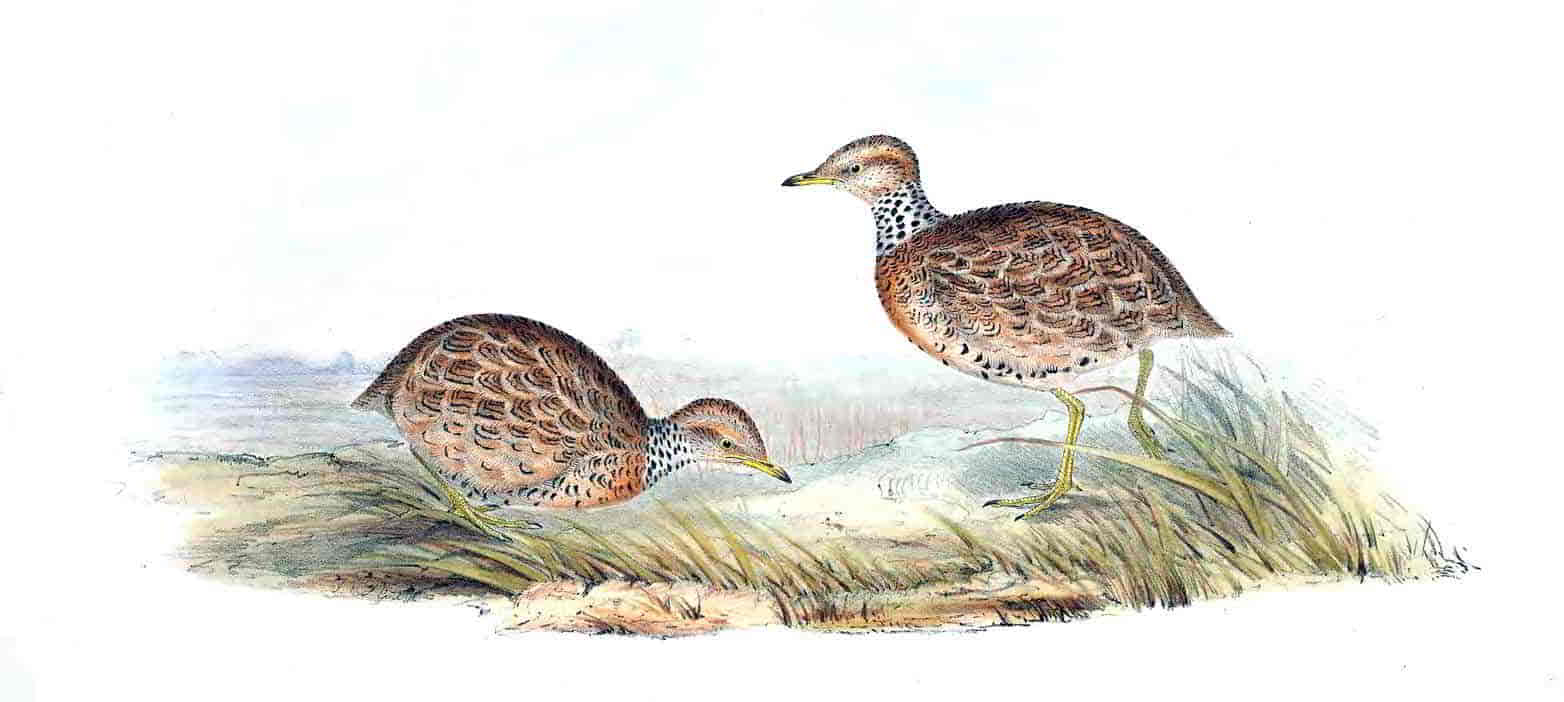

| Pedionomus torquatus, Gould | Collared Plain Wanderer | 80 |

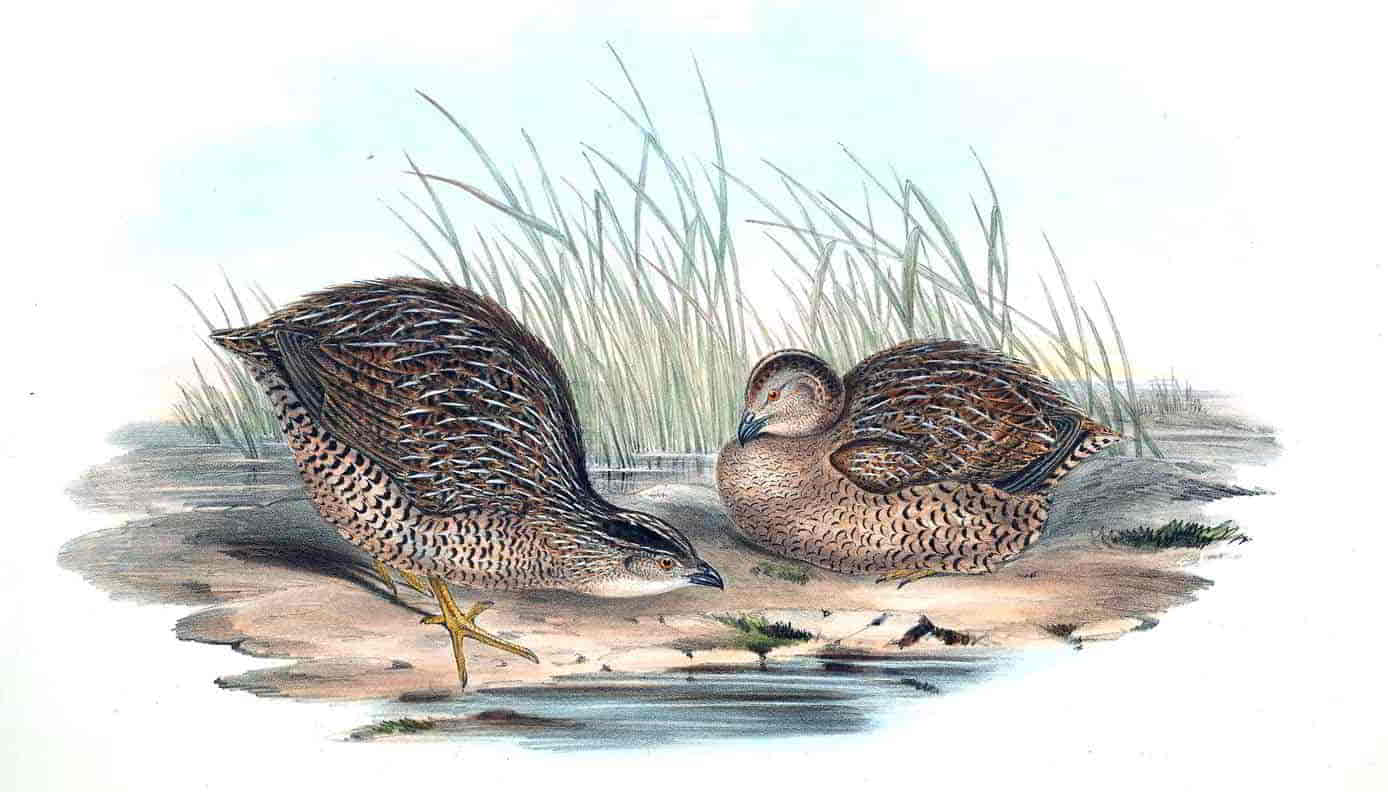

| Hemipodius[2] melanogaster, Gould | Black-breasted Hemipode | 81 |

| —— varius | Varied Hemipode | 82 |

| —— scintillans, Gould | Sparkling Hemipode | 83 |

| —— melanotus, Gould | Black-backed Hemipode | 84 |

| —— castanotus, Gould | Chestnut-backed Hemipode | 85 |

| —— pyrrhothorax, Gould | Red-chested Hemipode | 86 |

| —— velox, Gould | Swift-flying Hemipode | 87 |

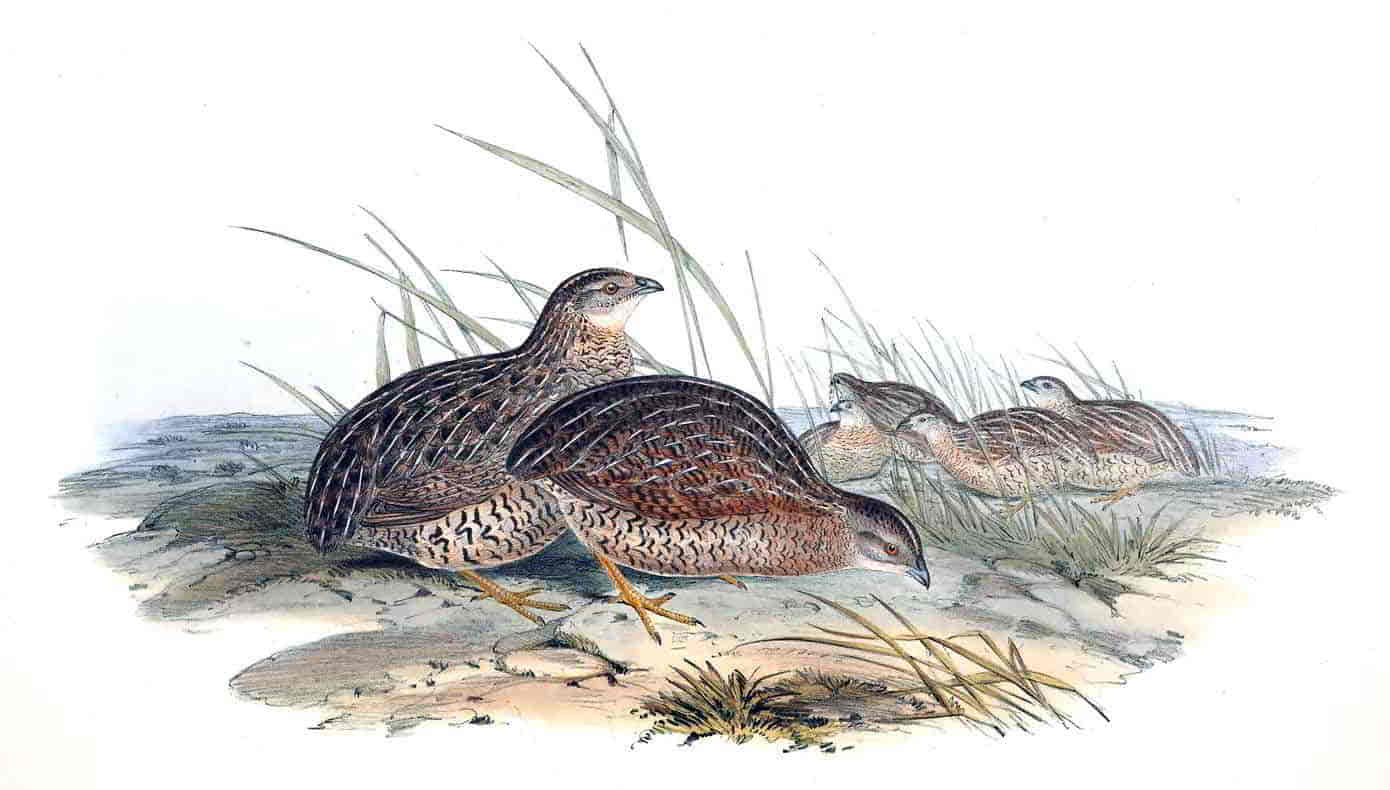

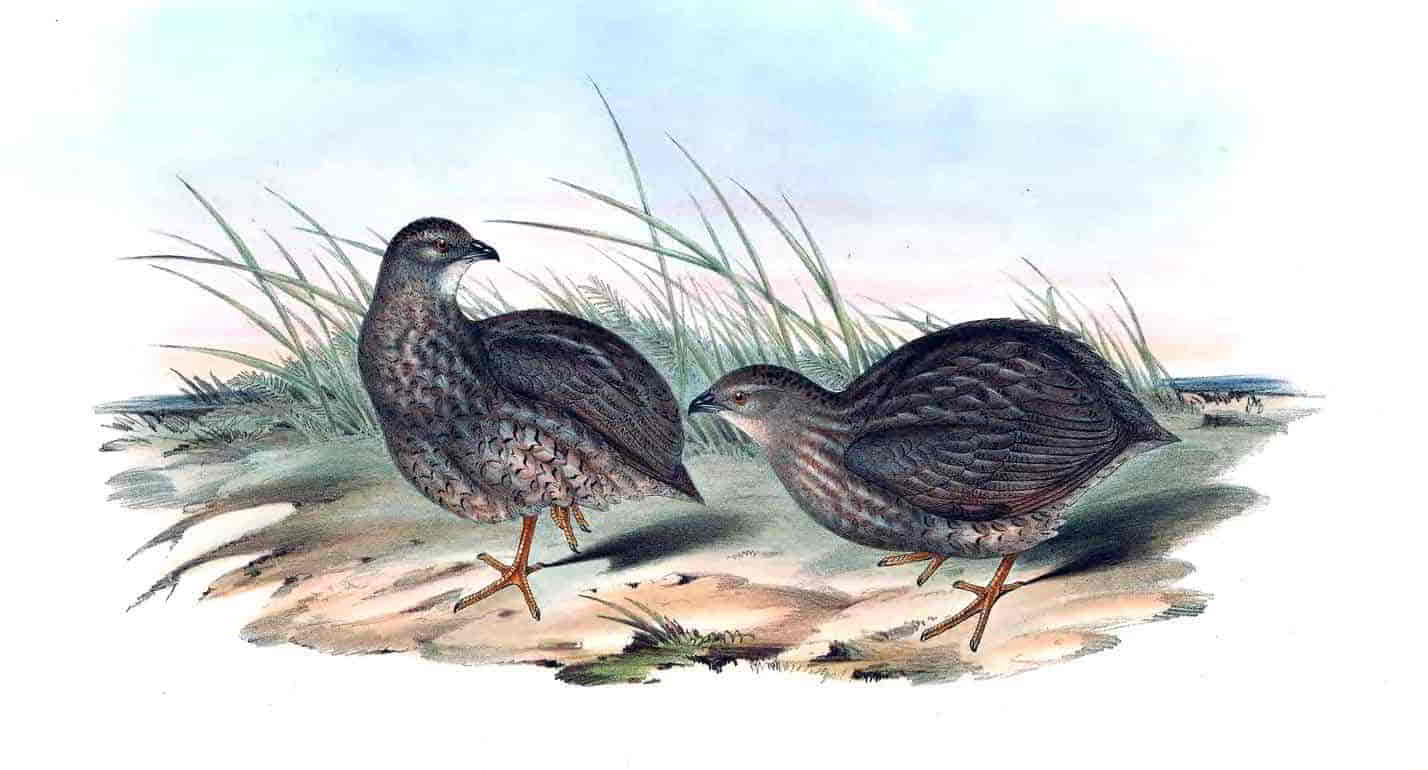

| Coturnix pectoralis, Gould | Pectoral Quail | 88 |

| Synoïcus Australis | Australian Partridge | 89 |

| —— Diemenensis, Gould | Van Diemen’s Land Partridge | 90 |

| —— sordidus, Gould | Sombre Partridge | 91 |

| ——? Chinensis | Chinese Quail | 92 |

1. Phaps being the generic appellation generally adopted, Peristera, under which term the birds of this form have been published, must sink into a synonym.

2. Turnix for the like reason must be substituted for Hemipodius, the term employed.

CACATUA GALERITA: Vieill.

J. Gould and H.C. Richter del et lith. C. Hullmandel Imp.

CACATUA GALERITA, Vieill.

Crested Cockatoo.

The Crested Cockatoo, White’s Journ., pl. in p. 237.

Psittacus galeritus, Lath. Ind. Orn., vol. i. p. 109; and Gen. Syn. Supp., vol. ii. p. 92.—Kuhl, Consp. Psitt. in Nov. Act., vol. x. p. 87.

Great Sulphur-crested Cockatoo, Shaw, Gen. Zool., vol. viii. p. 479.

Crested Cockatoo, Lath. Gen. Hist., vol. ii. p. 205.

Cacatua galerita, Vieill. 2nde Edit, du Nouv. Dict. d’Hist. Nat., tom. xvii. p. 11; and Ency. Méth. Orn., Part III. p. 1414.—Wagl. Mon. Psitt. in Abhand., p. 695.

Plyctolophus galeritus, Vig. and Horsf. in Linn. Trans., vol. xv. p. 268.—Vig. in Lear’s Ill. Psitt. pl. 3.—Steph. Cont. of Shaw’s Gen. Zool., vol. xiv. p. 108.

Cacatua chrysolophus, Less. Traité d’Orn., p. 182.

Car’away and Cur’riang, Aborigines of New South Wales.

Mangarape, Papuans of New Guinea.

If we regard the White Cockatoo of Van Diemen’s Land, that of the continent of Australia, and that of New Guinea as mere varieties of each other, this species has a more extensive range than most other birds. It is an inhabitant of all the Australian colonies, both on the southern and northern coasts, but has not yet been observed on the western.

On a close examination of specimens from the three countries above mentioned, a decided difference is observable in the structure of the bill, but of too trivial a character, in my opinion, to warrant their being considered as distinct; in fact, it would seem to be merely a modification of the organ for the peculiar kind of food afforded by the respective countries. The Van Diemen’s Land bird is the largest in every respect, and has the bill, particularly the upper mandible, less abruptly curved, exhibiting a tendency to the form of that organ in the genus Licmetis: the bill of the New Guinea bird is much rounder, and is, in fact, fitted to perform a totally different office from that of the White Cockatoo of Van Diemen’s Land, which I have ascertained, by dissection, subsists principally on the small bulbs of the terrestrial Orchidaceæ, for procuring which its lengthened upper mandible is admirably adapted; while it is more than probable that no food of this kind is to be obtained by the New Guinea bird, the structure of whose bill indicates that hard seeds, nuts, &c. constitute the principal part of its diet. The crops and stomachs of those killed in Van Diemen’s Land were very muscular, and contained seeds, grain, native bread (a species of fungus), small tuberous and bulbous roots, and, in most instances, large stones.

As may be readily imagined, this bird is not upon favourable terms with the agriculturist, upon whose fields of newly-sown grain and ripening maize it commits the greatest devastation; it is consequently hunted and shot down wherever it is found, a circumstance which tends much to lessen its numbers; it is still, however, very numerous, moving about in flocks varying from a hundred to a thousand in number, and evinces a decided preference to the open plains and cleared lands, rather than to the dense brushes near the coast. Except when feeding, or reposing on the trees after a repast, the presence of a flock, if not seen, is certain to be indicated by their horrid screaming notes, the discordance of which may be slightly conceived by those who have heard the peculiarly loud, piercing, grating scream of the bird in captivity, always remembering the immense increase of the din occasioned by the large number of birds emitting their disagreeable notes at the same moment; still I ever considered this annoyance amply compensated for by their sprightly actions and the life their snowy forms imparted to the dense and never-varying green of the Australian forest; a feeling participated in by Sir Thomas Mitchell, who says that “amidst the umbrageous foliage, forming dense masses of shade, the white Cockatoos sported like spirits of light.”

The situations chosen by this bird for the purpose of nidification vary with the nature of the locality it inhabits; the eggs are usually deposited in the holes of trees, but they are also placed in fissures in the rocks wherever they may present a convenient site: the crevices of the white cliffs bordering the Murray, in South Australia, are annually resorted to for this purpose by thousands of this bird, and are said to be completely honeycombed by them. The eggs are two in number, of a pure white, rather pointed at the smaller end, one inch and seven lines long by one inch two and a half lines broad.

All the plumage white, with the exception of the elongated occipital crest, which is deep sulphur-yellow, and the ear-coverts, centre of the under surface of the wing, and the basal portion of the inner webs of the tail-feathers, which are pale sulphur-yellow; irides and bill black; orbits white; feet greyish brown.

The figures are somewhat smaller than the natural size.

CACATUA LEADBEATERI: Wagl.

J. Gould and H.C. Richter del et lith. C. Hullmandel Imp.

CACATUA LEADBEATERI, Wagl.

Leadbeater’s Cockatoo.

Plyctolophus Leadbeateri, Vig. in Proc. of Comm, of Sci. and Corr. of Zool. Soc., Part I. p. 61; Lear’s Ill. Psitt. pl. 5; and in Phil. Mag. 1831, p. 55.—Gould in Syn. of Birds of Australia, Part IV.—Mitch. Australian Expeditions, vol. ii. p. 47.

Cacatua Leadbeateri, Wagl. Mon. Psitt, in Abhand., p. 692.

Jak-k̏ul-yȁk-kul, Aborigines of the mountain districts of Western Australia.

Pink Cockatoo, Colonists of Swan River.

This beautiful species of Cockatoo enjoys a wide range over the southern portions of the Australian continent; it never approaches very near the sea, but evinces a decided preference for the belts of lofty gums and scrubs clothing the sides of the rivers of the interior of the country; it annually visits the Toodyay district of Western Australia; and, as I ascertained, it annually breeds at Gawler in South Australia. On reading the works of Sturt and Mitchell, I find that both those travellers met with it in the course of their explorations, particularly on the hanks of the rivers Darling and Murray; in fact, most of the interior districts between New South Wales and Adelaide are inhabited by it: future research alone will determine the extent of its range to the northward; as yet no specimen has been received either from the north or north-west coasts.

It must be admitted that this species is at once the most beautiful and elegant of the genus yet discovered, and it will consequently ever be most highly prized for the cage and the aviary; two examples, now in the possession of the Earl of Derby, appear to bear confinement equally as well as any of their congeners; in their disposition they are not so sprightly and animated, but at the same time they are much less noisy, a circumstance which tends to enhance rather than decrease our partiality for them.

Few birds tend more to enliven the monotonous hues of the Australian forests than this beautiful species, whose “pink-coloured wings and glowing crest,” says Sir T. Mitchell, “might have embellished the air of a more voluptuous region.”

Its note is more plaintive than that of C. galerita, and does not partake of the harsh grating sound peculiar to that species.

General plumage white; forehead, front and sides of the neck, centre of the under surface of the wing, middle of the abdomen, and the basal portion of the inner webs of the tail-feathers tinged with rose-colour, becoming of a rich salmon-colour under the wing; feathers of the occipital crest crimson at the base, with a yellow spot in the centre and white at the tip; bill light horn-colour; feet dark brown.

The sexes are nearly equal in size; but the female has the yellow spots in the centre of the crest more conspicuous and better defined than her mate, whose crest, although larger, is not so diversified in colour as that of his mate; on the other hand, the salmon tint of the under surface is much more intense in the male than in the female.

The Plate represents the two sexes about the natural size.

CACATUA SANGUINEA: Gould.

J. Gould and H.C. Richter del et lith. C. Hullmandel Imp.

CACATUA SANGUINEA, Gould.

Blood-stained Cockatoo.

Cacatua sanguinea, Gould in Proc. of Zool. Soc., Part X. p. 138.

The circumstance of this species never having been characterized until I described it in the “Proceedings of the Zoological Society,” above quoted, may doubtless be attributed to its being solely an inhabitant of the north and north-west coasts of Australia, portions of the country where few collections have been formed. With the exception of a specimen brought home by Captain Chambers, R.N., and another in the collection of Mr. Bankier, my own specimens are all that I have ever seen; the whole of these were collected at Port Essington.

The Blood-stained Cockatoo inhabits swamps and wet grassy meadows, and is often to be seen in company with its near ally the Cacatua galerita, but I am informed it is even more shy and difficult of approach than that bird. It is doubtless attracted to the swampy districts by the various species of Orchidaceous plants that grow in such localities, upon the roots of which at some seasons it mainly subsists.

But little difference occurs either in the size or the colouring of the sexes, and I have young birds, which, although a third less in size, closely assimilate in every respect to the adult, so much so that an examination of the bill, which during immaturity is soft and yielding to the touch, is necessary to distinguish them.

I have never yet observed this species in collections from New Guinea; but I think it more than likely that its range may extend to that island, the fauna of which is at present so imperfectly known to us.

All the plumage white; base of the feathers of the lores and sides of the face stained with patches of blood-red; base of the inner webs of the primaries, secondaries and tail-feathers fine sulphur-yellow; bill yellowish white; feet mealy brown.

The figures are those of a male and a female about the natural size.

CACATUA EOS.

J. Gould and H.C. Richter del et lith. Hullmandel & Walton Imp.

CACATUA EOS.

Rose-breasted Cockatoo.

Psittacus Eos, Kuhl, Nova Acta, tom. x. p. 88.—Temm. Pl. Col., 81.

Cacatua rosea, Vieill. Gal. des Ois., tom. ii. p. 5. pl. 25.—Ib. Ency. Méth. Orn., Part iii. p. 1414.—Less. Traité d’Orn., p. 183.

Plyctolophus Eos, Vig. and Horsf. in Linn. Trans., vol. xv. p. 269.

Rose-coloured Cockatoo, Lath. Gen. Hist., vol. ii. p. 207.

Cacatua roseicapilla, Wagl. Mon. Psitt, in Abhand., pp. 504, 691.

—— Eos, Less. Man. d’Orn., tom. ii. p. 143.

The Rose Cockatoo, Sturt’s Travels in Australia, vol. ii. pl. in p. 79.

This beautiful Cockatoo is abundantly dispersed over a great part of the interior of Australia; both Oxley and Sturt speak of it as inhabiting the country to the north-west of the Blue Mountain range of hills; in fact, few travellers have visited the interior without having had their attention attracted by its appearance; and I saw it in great numbers on the plains bordering the river Namoi, particularly under the Nundewar range of Sir Thomas Mitchell; I possess specimens also from the north coast, procured by the Officers of the Beagle. A difference however, which may hereafter prove to be specific, exists between the birds from New South Wales and those of the north coast. Those from the latter locality are the largest in size, and have the bare skin round the eye more extended; the rosy colour of the breast and the grey colouring of the back are darker than in the specimens I killed on the Namoi.

The Rose-breasted Cockatoo possesses considerable power of wing, and like the house-pigeon of this country, frequently passes in flocks over the plains with a long sweeping flight, the group at one minute displaying their beautiful silvery grey backs to the gaze of the spectator, and at the next by a simultaneous change of position bringing their rich rosy breasts into view, the effect of which is so beautiful to behold, that it is a source of regret to me that my readers cannot participate in the pleasure I have derived from the sight. I was informed by the natives of the Namoi that the bird had so recently arrived in the district, that until within the last two years it had never been seen; they supposed it to have migrated from the north or interior of the country. During the years 1839 and 1840 it bred in considerable numbers in the boles of the large Eucalypti skirting the Nundewar range before alluded to, and afforded an abundant supply of young ones for the draymen and stock-keepers to transport to Sydney, where they are sold for a considerable sum to be shipped to England; and as they are very hardy, and bear cold and confinement extremely well, and are perfectly contented in a cage, we have, perhaps, more of them living in England at the present time than of any other species of the genus. I have seen it as tame in Australia as the ordinary denizens of the farm-yard, enjoying perfect liberty, and coming round the door to receive food in company with the pigeons and poultry, amongst which it mingled on terms of intimate friendship.

In a letter received from my friend Captain Sturt, he says, “The Rose-breasted Cockatoo is a bird of the low country entirely and limited in the extent of its habitat, never being found in any great number on the banks of the Darling, or rising higher than 600 feet above the level of the sea. It feeds on Salsolæ, and occupies those vast plains which lie immediately to the westward of the Blue Mountains. It has a peculiar flight, and the whole flock turning together show the rose-colour of the under surface with pretty effect.” I have not yet seen specimens of this bird from any part of the Swan River colony, neither did I observe it in any part of South Australia that I visited; the eastern and northern portions of Australia are evidently those most frequented by it.

The eggs, which are white, are generally three in number, about an inch and a half long by an inch and an eighth broad.

The young at first are covered with long, fine downy feathers, which at an early age give place to the colours which characterize the plumage of the adult.

The sexes do not differ in colouring and scarcely in size, but individuals differ considerably in the depth of the tint of the under surface, some being much deeper than others, and in the extent of the bare space round the eye.

Crown of the head pale rosy white; all the upper surface grey, deepening into brown at the extremity of the wings and tail, and becoming nearly white on the rump and upper tail-coverts; sides of the neck, all the under surface from below the eyes and the under surface of the shoulder rich deep rosy red; thighs and under tail-coverts grey; irides rich deep rosy red; orbits brick-red; bill white; feet mealy dark brown.

The figures are of the natural size.

LICMETIS NASICUS.

J. Gould and H.C. Richter del et lith. Hullmandel & Walton Imp.

LICMETIS NASICUS.

Long-billed Cockatoo.

Psittacus nasicus, Temm, in Linn. Trans., vol. xiii. p. 115.—Ib. Pl. Col, 331.

Long-nosed Cockatoo, Lath. Gen. Hist., vol. ii. p. 205.

Licmetis tenuirostris, Wagl. Mon. Psitt, in Abhand., vol. i. pp. 505 and 695.—G. R. Gray, List of Gen. of Birds, 2nd edit. p. 69.

Psittacus tenuirostris, Kuhl in Nov. Acta, tom. x. p. 88.

Cacatua nasica, Less. Traité d’Orn., p. 183.

Plyctolophus tenuirostris, Steph. Cont. of Shaw’s Gen. Zool., vol. xiv. p. 108.

The Red-vented Cockatoo, Brown’s Ill., p. 10. pl. 5.

As I regard the Long-billed White Cockatoos from Western Australia and New South Wales as distinct, the habitat of the present species, so far as is yet known, is confined to the districts of Port Philip and South Australia, where it inhabits the interior rather than the neighbourhood of the coast. Like the common Cacatua galerita, it assembles in large flocks and spends much of its time on the ground, where it grubs up the roots of Orchids and other bulbous plants upon which it mainly subsists, and hence the necessity for its singularly-formed bill. It not unfrequently makes inroads to the newly-sown fields of corn, where it is the most destructive bird imaginable. It passes over the ground in a succession of hops, much more quickly than the Cacatua galerita; its powers of flight also exceed those of that bird, not perhaps in duration, but in the rapidity with which it passes through the air. I noticed this particularly when a flock passed me in the interior of South Australia. I have seen many individuals of this species in captivity, both in New South Wales and in this country; and although they appear to bear confinement equally as well as the other members of the family, they seemed more dull and morose, and of a very irritable temper.

The eggs, which are white, two in number, and about the size of those of the Cacatua galerita, are usually deposited on a layer of rotten wood at the bottom of holes in the larger gum-trees.

The sexes are alike in colour and size.

The general plumage white, washed with pale brimstone-yellow on the under surface of the wing, and with bright brimstone-yellow on the under surface of the tail; line across the forehead and lores scarlet; the feathers of the head, neck and breast are also scarlet at the base, showing through the white, particularly on the breast; irides light brown; bill white; naked skin round the eye greenish blue; legs and feet dull olive-grey.

The two figures in the accompanying Plate are rather less than the natural size.

NESTOR PRODUCTUS. (Gould)

Drawn from Nature & on stone by J & E Gould. Printed by C. Hullmandel.

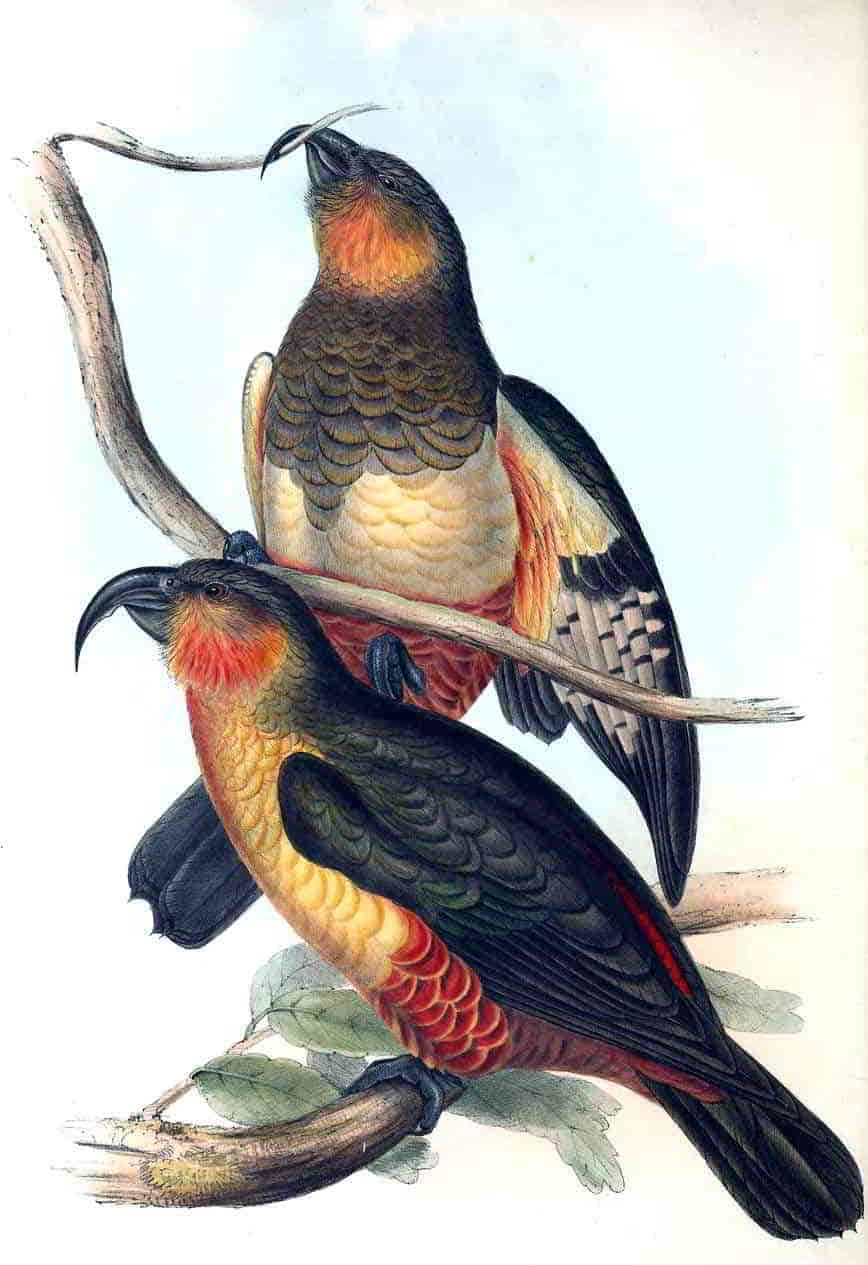

NESTOR PRODUCTUS, Gould.

Phillip Island Parrot.

Wilson’s Parrakeet, Lath. Gen. Hist., vol. ii. p. 170.?

Long-billed Parrakeet, Ib., p. 171.?

Plyctolophus productus, Gould in Proc. of Zool. Soc., Part IV. 1836, p. 19.

Nestor productus, Gould, Syn. of the Birds of Australia, Part I.

I have considerable pleasure in being enabled to add a second and so beautiful a species as the present to the genus Nestor of Wagler. Like its near ally, the N. hypopolius, which, so far as is yet known, is only found in New Zealand, the N. productus has a very limited habitat, the entire race, as I am credibly informed, being confined to Phillip Island, whose whole circumference is not more than five miles in extent; so strictly in fact is it confined to this isolated spot, that many persons who have resided in Norfolk Island for years, have assured me its occurrence there is never known, although the distance from one island to the other is not more than three or four miles. I regret to state, that, in consequence of the settlement of Norfolk Island, the native haunts of this fine bird have been so intruded upon, and such a war of extermination been carried on against it, that if such be not the case already, the time is not far distant when the species will be completely extirpated, and, like the Dodo, its skin and bones become the only mementos of its existence.

Had I been able to visit Norfolk and Phillip Islands, I should certainly have made every inquiry into the native habits and economy of this very singular form among the Parrots, the nature of its food, mode of procuring it, &c.; and I would now urge the necessity of these investigations upon those who may be favourably situated for making them. Like all the other members of the extensive family of Psittacidæ, it bears captivity remarkably well, readily becoming contented, cheerful, and an amusing companion. During my stay at Sydney, I had an opportunity of seeing a living example in the possession of Major Anderson, and was much interested with many of its actions, which were so different from those of every other member of its family, that I felt convinced they were equally different and curious in a state of nature. This bird was not confined to a cage, but permitted to range over the house, along the floors of which it passed, not with the awkward waddling gait of a Parrot, but in a succession of leaps, precisely after the manner of the Corvidæ. Mrs. Anderson, to whom I am indebted for the little I could learn respecting it, informed me that it is found among the rocks and upon the loftiest trees of the island, that it is so tame as to be readily taken alive with a noose, and that it feeds upon the blossoms of the white-wood tree, or white Hibiscus, sucking the honey of the flowers: the mention of this latter circumstance induced me to examine the tongue of the bird, which presented a very peculiar structure, not, like that of the true honey-feeding Parrakeets (the Trichoglossi), furnished with a brush-like termination, but with a narrow horny scoop on the under side, which, together with the extremity of the tongue, resembled the end of a finger with the nail beneath instead of above: this peculiarity in the structure of the organ is doubtless indicative of a corresponding peculiarity in the nature of the food upon which the bird subsists. I may mention that Sir J. P. Millbank, Bart., informed me that a living example of this species in his possession evinced a strong partiality to the leaves of the common lettuce and other soft vegetables, and that it was also very fond of the juice of fruits, of cream and butter.

Mrs. Anderson told me that it lays four eggs in the hollow part of a tree, but beyond this I was unable to ascertain anything respecting its nidification.

Its voice is a hoarse, quacking, inharmonious noise, sometimes resembling the barking of a dog.

It would appear from the numerous specimens I have examined that the sexes scarcely differ from each other in colour; the young, on the contrary, have but little of the rich yellow and red markings of the breast, that part being olive-brown like the back.

The general colour of the upper surface brown; head and back of the neck tinged with grey, the feathers of these parts as well as of the back margined with a deeper tint; rump, belly, and under tail-coverts deep red; cheeks, throat, and chest yellow, the former tinged with red; shoulders on their inner surface yellow tinged with rufous olive; tail-feathers banded at the base with orange-yellow and brown; the inner webs of the quill-feathers at the base and beneath, with dusky red and brown; irides very dark brown; bill brown; nostrils, bare skin round the eye, and feet dark olive-brown.

Our Plate represents an old and a nearly adult bird, exhibiting traces of the immature plumage on the chest, of the natural size.

CALYPTORHYNCHUS BANKSII.

J. Gould and H.C. Richter del et lith. Hullmandel & Walton Imp.

CALYPTORHYNCHUS BANKSII.

Banksian Cockatoo.

Psittacus Banksii, Lath. Ind. Orn., vol. i. p. 107.—Ib. Gen. Syn., p. 63, p. 109.—Parkinson’s Voy., p. 144.—Cook’s Voy., vol. ii. p. 18.—Shaw, Gen. Zool., vol. viii. p. 476.—Lath. Gen. Hist., vol. ii. p. 199. pl. 27 (female).

Psittacus magnificus, Shaw, Nat Misc., pl. 50.

Calyptorhynchus Banksii, Vig. and Horsf. in Linn. Trans., vol. xv. p. 271.

—— stellatus, Wagl. Mon. Psitt. in Abhand., tom. i. p. 683. pl. 27 (a very young bird).—Selby in Nat. Lib. Orn., vol. vi. Parrots, p. 134.

I have abundant reasons for stating that every portion of Australia yet visited by Europeans is inhabited by members of the genus Calyptorhynchus, and that at least six species are now known, each of which has its own peculiar limits, beyond which it seldom or never passes. The present species, which is one of those with which we first became acquainted, and to which, as will be seen above, several specific appellations have been given, is a native of New South Wales, out of which colony I have never known it to occur, its range appearing to be limited by Moreton Bay on the east and Port Philip on the south. It is not unfrequently seen in the immediate neighbourhood of Sydney and other large towns, and it alike frequents the brushes and the more open wooded parts of the colony, where it feeds on the seeds of the Banksiæ and Casuarinæ, changing its diet however, as occasion may offer, to caterpillars, particularly those that infest the wattles and other low trees. The facility with which it procures these large grubs is no less remarkable than the structure of the bird’s bill, which is admirably adapted for scooping out the wood of both the larger and smaller branches, and by this means obtaining possession of the hidden treasure.

The Banksian Cockatoo is a suspicious and shy bird, and it requires a considerable degree of caution to approach it within gun-shot; there are times however, particularly when it is feeding, when this may be more readily accomplished. It never assembles in large flocks like the White Cockatoo, but moves about either in pairs or in small companies of from four to eight in number. Its flight is heavy, and the wings are moved with a flapping, laboured motion; it seldom mounts high in the air, for although its flight is somewhat protracted, and journeys of several miles are performed, it rarely rises higher than is sufficient to surmount the tops of the lofty Eucalypti, a tribe of trees it often frequents, and in the larger kinds of which it almost invariably breeds, depositing its two or three white eggs in some inaccessible hole, spout or dead limb, the only nest being the rotten wood at the bottom, or the chips made by the bird in forming an excavation.

The female and young birds of both sexes differ very considerably from the old male in the marking of their plumage, and hence has arisen no end of confusion and the various names assigned to this bird; the above list of synonyms has been worked out with considerable care, and will I believe be found correct.

It is with feelings of great pleasure that I find that the term Banksii, having the priority, the name of the illustrious Banks, will ever be retained as the distinctive appellation of this noble and ornamental bird; and I would that it were in my power to write as many pages respecting its habits and economy as I have lines; but this task must devolve upon some future historian of the productions of a country teeming with the highest interest, and who will doubtless find occupation in investigating the minute details of that respecting which I am only able to give a general outline.

The male has the entire plumage glossy greenish black, with a broad band of rich deep vermilion across the middle of all but the two central tail-feathers, and the external web of the outer feather on each side; feet mealy brown; bill in young specimens greyish white, in old specimens black.

The female has the general plumage glossy greenish black, each feather of the head, sides of the neck and wing-coverts pale yellow; under surface crossed by narrow irregular bars of pale yellow, becoming fainter on the abdomen; under tail-coverts crossed by narrow freckled bars of yellowish red; tail banded with red, passing into sulphur-yellow on the inner margins of the feathers, and interrupted by numerous narrow irregular bars and freckles of black.

The Plate represents the male and female about two-thirds of the natural size.

CALYPTORHYNCHUS MACRORHYNCHUS: Gould.

Gould and H. C. Richter del et lith. Hullmandel & Walton Imp.

CALYPTORHYNCHUS MACRORHYNCHUS, Gould.

Great-billed Black Cockatoo.

Calyptorhynchus macrorhynchus, Gould in Proc. of Zool. Soc., Part X. p. 138.

Lȁr-a-wuk, Natives of Taratong.

All the examples of this species that have come under my notice have been collected at Port Essington, where it is usually seen in small troops of from four to six in number. It has many characters in common with the Black Cockatoos of the south coast, but no species of the genus yet discovered has the bill so largely developed, which development is doubtless requisite to enable it to procure some peculiar kind of food at present unknown to us; it assimilates to the C. Cookii of New South Wales in the lengthened form of its crest, but differs in having much shorter wings, and in the mandibles being fully one-third larger. The females of the two species also vary considerably in the colouring of the bands across the tail-feathers, which in the C. Cookii is pure scarlet, while the same part of the female of the present bird is mingled yellow and scarlet. It differs from the C. naso of Western Australia in having a larger bill than that species, and in the much greater length of the crest; a similar difference is also observable in the colouring of the tail-feathers of the females that has been already pointed out with regard to C. Cookii.

It is a very powerful species, and its habits and economy are so similar to the other members of the genus that a description of them would be superfluous.

The male has the whole of the plumage glossy bluish black; lateral tail-feathers, except the external web of the outer one, crossed by a broad band of fine scarlet; bill horn-colour; irides blackish brown; feet mealy blackish brown.

The female has the general plumage as in the male, but with the crest-feathers, those on the sides of the face and neck, and the wing-coverts spotted with light yellow; each feather of the under surface, but particularly the chest, crossed by several semicircular fasciæ of yellowish buff; lateral tail-feathers crossed on the under surface by numerous irregular bands of dull yellow, which are broad and freckled with black at the base of the tail, and become narrower and more irregular as they approach the tip; on the upper surface of the tail these bands are bright yellow at the base of the feathers, and gradually change into pale scarlet as they approach the tip; irides blackish brown.

The Plate represents the two sexes about two-thirds of the natural size.

CALYPTORHYNCHUS NASO: Gould

J. Gould and H.C. Richter del et lith. Hullmandel & Walton Imp.

CALYPTORHYNCHUS NASO, Gould.

Western Black Cockatoo.

Calyptorhynchus naso, Gould in Proc. of Zool. Soc., Part IV. p. 106.

Kar-rak, Aborigines of the mountain and lowland, and

Keer-jan-dee of the Aborigines of the northern districts of Western Australia.

Red-tailed Black Cockatoo of the Colonists.

The characters by which this species is distinguished from the Calyptorhynchus macrorhynchus, are a smaller bill and a shorter and more rounded crest; the same characters, which I know to be constant, also distinguish it from the C. Banksii. The bill is inclined to be gibbose, like that of C. Leachii, to which species it also offers a further alliance in its shorter contour, rounded crest, and short tail.

The extent of range enjoyed by the Calyptorhynchus naso I have not been able to ascertain; its great stronghold appears to be the colony of Swan River, where it inhabits all parts of the country. As might be expected, its habits and economy closely resemble those of the other members of the genus. Except in the breeding-season, when it pairs, it may often be observed in companies of from six to fifteen in number.

It breeds in the holes of trees, making no nest, but merely collecting the soft dead wood on which to deposit its eggs, which are generally placed in trees so difficult of access that even the natives dislike to climb them. The eggs are four or five in number; the four given to Mr. Gilbert by the son of the colonial chaplain were taken by a native from a hole in a very high white gum-tree, in the last week of October; they are white, one inch and eight lines long by one inch and four lines broad.

It flies slowly and heavily, and while on the wing utters a very harsh and grating cry, resembling the native name.

The stomach is membranous and capacious, and the food of those examined contained seeds of the Eucalypti, Banksiæ, &c.

The sexes, which differ considerably in colour, may be thus described:—

The male has the entire plumage glossy greenish black; lateral tail-feathers, except the external web of the outer one, crossed by a broad band of fine scarlet; irides dark blackish brown; bill bluish lead-colour, becoming much paler on the under side of the lower mandible; feet brownish black, with a leaden tinge.

The female has the upper surface similar to, but not so rich as, that of the male, and has an irregularly shaped spot of yellowish white near the tip of each of the feathers of the head, crest, cheeks and wing-coverts; the under surface brownish black, crossed by numerous narrow irregular bars of dull sulphur-yellow; the under tail-coverts crossed by several irregular bars of mingled yellow and dull scarlet; the lateral tail-feathers dull scarlet, fading into yellow on the base of the inner webs, and crossed by numerous irregular bars of black, which are narrow at the base of the feathers and gradually increase in breadth towards the tip.

The Plate represents the two sexes about two-thirds of the natural size.

CALYPTORHYNCHUS LEACHII.

J. Gould and H.C. Richter del et lith. Hullmandel & Walton Imp.

CALYPTORHYNCHUS LEACHII.

Leach’s Cockatoo.

Psittacus Banksii, Lath. Ind. Orn., vol. i. p. 107. variety β.

Banksian Cockatoo, Lath. Gen. Syn. Supp., vol. ii. p. 91 A.—White’s Journ., pl. in p. 139.—Phil. Bot. Bay, pl. in p. 267.—Lath. Gen. Hist., vol. ii. p. 200 A.

Psittacus Cookii, Temm. in Linn. Trans., vol. xiii. p. 111.

———— Solandri, Temm. in Linn. Trans., vol. xiii. p. 113.

Solander’s Cockatoo, Lath. Gen. Hist., vol. ii. p. 201.

Cook’s Cockatoo, Lath. Gen. Hist., vol. ii. p. 201.

Psittacus Leachii, Kuhl, Consp. Psitt, in Nov. Acta, vol. x. p. 91. pl. 3.

———— Temminckii, Kuhl, Consp. Psitt, in Nov. Acta, vol. x. p. 89.

Calyptorhynchus Cookii, Vig. and Horsf. in Linn. Trans., vol. xv. p. 272.

———— Solandri, Vig. and Horsf. in Linn. Trans., vol. xv. p. 274.

———— Leachii, Wagl. Mon. Psitt, in Abhand., vol. i. p. 683.

———— Temminckii, Wagl. Mon. Psitt, in Abhand., vol. i. p. 684.

———— stellatus, Selb. in Nat. Lib. Orn., vol. vi. Parrots, p. 134. pl. 15.

Carat, Aborigines of New South Wales.

The Calyptorhynchus Leachii is the least species of the genus yet discovered, and independently of its smaller size, it may be distinguished from its congeners by the more swollen and gibbose form of its bill. Its native habitat is New South Wales and South Australia. I obtained specimens of it on the Lower Namoi, more than three hundred miles in the interior; and the cedar brushes of the Liverpool range, Mr. Charles Throsby’s park at Bong-bong, and the sides of the creeks of the Upper Hunter, were also among the places in which I killed it. So invariably did I find it among the Casuarinæ, that those trees appeared to be as essential to its existence as the Banksiæ are to that of some species of Honey-eater. The crops of those I killed were invariably filled with the seeds of the trees in question. Its disposition is less shy and distrusting than those of the Calyptorhynchi Banksii and funereus, but little stratagem being required to get within gun-shot; when one is killed or wounded, the rest of the flock either fly around or perch on the neighbouring trees, and every one may be procured. It has the feeble, whining call of the other members of the genus. Its flight is laboured and heavy; but when it is necessary for it to pass to a distant part of the country, it mounts high in the air and sustains a flight of many miles.

It is not unusual to find individuals of this species with yellow feathers on the cheeks and other parts of the head; this variation I am unable to account for; it is evidently subject to no law, as it frequently happens that six or eight may be seen together without one of them exhibiting this mark, while on the contrary a like number may be encountered with two or three of them thus distinguished. To this circumstance, and to the variation in the colouring of the tail-feathers of the two sexes, may be attributed the voluminous list of synonyms pertaining to this species.

Why living examples of the members of this genus have not as yet reached Europe, is not easily to be accounted for. I found no difficulty in keeping a winged bird alive for a short time, and I doubt not that were the attempt made, it might be easily introduced to our aviaries; the real cause probably is the extreme difficulty of procuring young individuals, the breeding-place selected by the bird being holes in the highest trees situated in the most remote parts of the forests, where none but the Aborigines are likely to discover or able to procure them.

There is no doubt that Mr. Caley is right in the opinion expressed in his notes that this is the Carat of the natives; and he adds that it lays two eggs in the holes of the trees; “does not cut off the branches of trees like the Cal. funereus, but cuts off May-rybor-ro and Mun-mow (the fruit of two species of Persoonia), without however eating them, before they are ripe, to the great injury and vexation of the natives.”

The adult male may at all times be distinguished from the female by the broad band of scarlet on the tail. The females and males during the first year have this part banded with black, as shown in the accompanying Plate.

The old male has the entire plumage glossy greenish black, washed with brown on the head and neck, with a broad band of deep vermilion across the middle of all but the two centre tail-feathers, and the external web of the outer feather on each side; irides very dark brown; orbits mealy black in some, in others pinky; bill dark horn-colour; feet mealy black.

The females and young males differ in having the head and neck browner than in the adult male, and in having the scarlet band on the tail crossed by narrow bands of greenish black.

The figures are nearly the size of life.

CALYPTORHYNCHUS FUNEREUS.

J. Gould and H.C. Richter del et lith. Hullmandel & Walton Imp.

CALYPTORHYNCHUS FUNEREUS.

Funereal Cockatoo.

Psittacus funereus, Shaw, Nat. Misc., pl. 186.—Kuhl, Consp. Psitt. in. Nova Acta, etc., vol. x. p. 89.—Lath. Ind. Orn. Suppl., vol. i. p. xxii.

Funereal Cockatoo, Lath. Gen. Hist., vol. ii. p. 202.

Banksian Cockatoo, Lath. Gen. Syn. Suppl., vol. i. p. 91. C.—Shaw, Gen. Zool., vol. viii. p. 477.

Calyptorhynchus funereus, Vig. and Horsf. in Linn. Trans., vol. xv. p. 271.

Plyctolophus funeralis, Swains. Class. of Birds, vol. ii. p. 302.

Wy-la, Aborigines of the Upper Hunter in New South Wales.

Although not the most powerful in its mandibles, the present bird is the largest species of the genus to which it belongs, its large wings and expansive tail being unequalled by those of any other member of the great family of Psittacidæ yet discovered. The true habitat of the Calyptorhynchus funereus is New South Wales, or that portion of the Australian continent forming its south-eastern division. Among other places, I observed it in the neighbourhood of Sydney, at Bong-bong, on Mosquito Island near the mouth of the River Hunter, and on the Liverpool range; and it may be said to be universally distributed over this part of the continent. The thick brushes clothing the mountain sides and bordering the coast-line, the trees of the plains and the more open country are equally frequented by it; at the same time it is nowhere very numerous, but is usually met with associated in small companies of from four to eight in number, except during the breeding season, when it is only to be seen in pairs. Its food is much varied; sometimes the great belts of Banksias are visited, and the seed-covers torn open for the sake of their contents; while at others it searches with avidity for the larvæ of the large caterpillars which are deposited in the wattles and gums. Its flight, as might be expected, is very heavy, flapping and laboured, but it sometimes dives about between the trees in a most rapid and extraordinary manner.

When busily engaged in scooping off the bark in search of its insect food, it may be approached very closely; and if one be shot, the remainder of the company will fly round for a short distance and perch on the neighbouring trees, until the whole are brought down, if you are desirous of so doing.

Its note is very singular,—a kind of whining call, which it is impossible to describe, but which somewhat resembles the syllables Wy-la, whence the native name.

The eggs, which are white and two in number, about one inch and five-eighths long by one inch and three-eighths broad, are deposited on the rotten wood in the hollow branch of a large gum.

Caley mentions that this bird has a habit of cutting off the smaller branches of the apple-trees (Anophoræ), apparently from no other than a mischievous motive.

The sexes are very nearly alike, and may be thus described:—

The general plumage brownish black, glossed with green, particularly on the head; feathers of the body, both above and beneath, narrowly margined with brown; ear-coverts dull wax-yellow; all but the two central tail-feathers crossed in the centre by a broad band, equal to half their length, of brimstone-yellow, thickly freckled with irregular zigzag markings of brownish black; the external web of the outer primary on each side, and the margin of the external web of the other banded feathers, brownish black; bill black in some and white in others, the latter being probably young birds; eyes blackish brown; feet mealy blackish brown; orbits in some black, in others pinkish red, and in others whitish.

The figure is about two-thirds of the natural size.

CALYTORHYNCHUS XANTHONOTUS: Gould.

J. Gould and H.C. Richter del et lith. Hullmandel & Walton Imp.

CALYPTORHYNCHUS XANTHONOTUS, Gould.

Yellow-eared Black Cockatoo.

Calyptorhynchus xanthonotus, Gould in Proc. of Zool. Soc., Part V. p. 151; and in Syn. Birds of Australia, Part IV.

The great stronghold of this species is Van Diemen’s Land, but I have also seen specimens from Flinders’ Island and South Australia, in all of which countries it is the representative of the Calyptorhynchus funereus of New South Wales. It is very plentifully dispersed over all parts of Van Diemen’s Land, where it evinces a preference for the thickly wooded and mountainous districts; and is always to be observed in the gulleys under Mount Wellington, particularly in the neighbourhood of New Town. In fine weather it takes a higher range, but descends to the lower part of the country on the approach of rain, when it becomes excessively noisy, and utters as it flies a very peculiar whining cry. Its flight, from the enormous size of its wings, appears to be heavy and laborious, and while performing this action it presents a very remarkable appearance, its short neck, rounded head, and long wings and tail giving it a very singular contour. It is generally to be observed in companies of from four to ten in number, but occasionally in pairs only. I found it very shy and difficult of approach, which may perhaps be attributed to its being wantonly shot wherever it may be met with.

Its principal food is a large kind of caterpillar, which it obtains from the wattle- and gum-trees, and in procuring which it displays the greatest activity and perseverance, scooping off the bark and cutting through the thickest branch until it arrives at the object of its search; it is in fact surprising to see what enormous excavations it makes in the larger branches, and how expertly it cuts across the smaller ones: besides these large caterpillars, it also feeds upon the larvæ of several kinds of coleopterous insects, and occasionally, but not generally, on the seeds of the Banksias and berries; chrysalides were also found in the stomachs of some that were dissected.

I found it exceedingly difficult to obtain any particulars respecting the nidification of this bird, in consequence of its resorting for the performance of this duty to the most retired and inaccessible parts of the forests. Lieut. Breton, R.N., having informed me that a pair were breeding in a tree on the estate of Mr. Wettenhall, I requested him to use his influence with that gentleman to have their eggs procured for me, and on the 2nd of February 1839, I received a note from him in which he says:—

“In compliance with your request, I wrote to Mr. Wettenhall upon the subject of the Black Cockatoo’s nest, and he forthwith directed his shepherd to fell the tree in which the bird had established itself. It was situated in a gulley or bottom, and was about four feet and a half in diameter. The hole was from ninety to one hundred feet from the ground, two feet in depth, and made quite smooth, the heart of the tree being decayed. There was no appearance whatever of a nest. The tree was broken in pieces by the fall, and the contents of the hole or nest destroyed; the fragments, however, were sought for with the greatest care, and all that could be found are sent you. It may perhaps be as well to state, that both while the tree was being felled and for a short time afterwards, a Hawk kept attacking the Cockatoo, which flew in circles round the tree before it fell, uttering its loudest and most mournful notes, and at times turning upon the Hawk, until at length it flew off.”

The eggs are white, from two to four in number, and one inch and eight lines long by one inch and four lines broad.

The bird varies considerably in size and weight, some specimens weighing as much as one pound and ten ounces, while others weighed no more than one pound and three ounces.

The sexes, which differ but little from each other, may be thus described:—

Crown of the head, cheeks, throat, upper and under surface brownish black; feathers of the breast obscurely tipped with dull olive; ear-coverts yellow; two centre tail-feathers deep blackish brown, the remainder black at the base and tips, the central portion being in some specimens uniform light lemon-yellow, and in others the same colour blotched with spots and markings of brown; bill in some specimens white, in others blackish brown; feet greyish brown; orbits in some black, in others pink; irides nearly black.

I believe the birds with white bills to be immature.

The figures are about two-thirds of the natural size.

CALYPTORHYNCHUS BAUDINII: Vig.

J. Gould and H.C. Richter del et lith. Hullmandel & Walton Imp.

CALYPTORHYNCHUS BAUDINII, Vig.

Baudin’s Cockatoo.

Calyptorhynchus Baudinii, Vig. in Lear’s Ill. Psitt., pl. 6.

Oo-l̏aak of the Aborigines of the lowland, and

Ngol-y̏e-nuk of the Aborigines of the mountain districts of Western Australia.

White-tailed Black Cockatoo of the Colonists.

This species, which is a native of Western Australia, is distinguished from all the other known members of the group by its smaller size and by the white markings of its tail-feathers. It belongs to that section of the Black Cockatoos in which a similarity of marking characterizes both sexes, such as Calyptorhynchus funereus and C. xanthonotus. Like the other members of the genus it frequents the large forests of Eucalypti and the belts of Banksiæ, upon the seeds of which it mainly subsists; occasionally it seeks its food on the ground, when insects, fallen seeds, &c. are equally partaken of; the larvæ of moths and other insects are also extracted by it from the trunks and limbs of such trees as are infested by them.

Its flight is heavy and apparently laboured: when on the wing it frequently utters a note very similar to its aboriginal name; at other times when perched on the trees it utters a harsh croaking sound, which is kept up all the time the bird is feeding.

It breeds in the holes of the highest white gum-trees, often in the most dense and retired part of the forest. The eggs are generally two in number, of a pure white; their average length being one inch and three-quarters by one inch and three-eighths in breadth. The breeding-season extends over the months of October, November and December.

Up to the time of writing this account I have never seen specimens from any other part of Australia than the colony of Swan River, over the whole of which it seems to be equally distributed.

The entire plumage is blackish brown, glossed with green, especially on the forehead; all the feathers narrowly tipped with dull white; ear-coverts creamy white; all but the two central tail-feathers crossed by a broad band, equal to half their length, of cream-white; the external web of the outer primary and the margin of the external web of the other banded feathers blackish brown; the shafts black; irides blackish brown; bill lead-colour; in some specimens the upper mandible is blackish brown; legs and feet dull yellowish grey, tinged with olive.

The figure represents a male about three-fourths of the natural size.

CALLOCEPHALON GALEATUM.

J. Gould and H.C. Richter del et lith. Hullmandel & Walton Imp.

CALLOCEPHALON GALEATUM.

Gang-gang Cockatoo.

Psittacus galeatus, Lath. Ind. Orn., Supp. p. xxiii.—Kuhl, Consp. Psitt, in Nova Acta, tom. x. p. 88.

Red-crowned Parrot, Lath. Gen. Syn., Supp. vol. ii. p. 369. pl. 140.—Shaw, Gen. Zool., vol. viii. p. 523.—Lath. Gen. Hist., vol. ii. p. 218. pl. xxviii.

Calyptorhynchus galeatus, Vig. and Horsf. in Linn. Trans., vol. xv. p. 274.—Less. Man. d’Orn., tom. ii. p. 144.

Corydon galeatus, Wagl. Mon. Psitt. in Abhand., vol. i. pp. 504 and 690.

Plyctolophus galeatus, Swains. Class. of Birds, vol. ii. p. 302.

Banksianus galeatus, Less. Traité d’Orn., p. 181.

Callocephalon Australe, Less.

Callocephalon galeatum, G. R. Gray, List of Gen. of Birds, 2nd edit., p. 68.

Cacatua galeata, Vieill. Nouv. Dict. d’Hist. Nat., tom. xvii. p. 12.—Ency. Méth., tom. iii. p. 1414.

Psittacus phœnicocephalus, Mus. de Paris.

Gang-gang Cockatoo, Colonists of New South Wales.

The only information I can give respecting this fine species is that it is a native of the forests bordering the south coast of Australia, some of the larger islands in Bass’s Straits, and the northern parts of Van Diemen’s Land, and that it frequents the most lofty trees and feeds on the seeds of the various Eucalypti. A few instances have occurred of its being brought to England alive, where it has borne captivity quite as well as the other members of the great family to which it belongs; thus affording sufficient evidence that the Black Cockatoos (Calyptorhynchi) would thrive equally well were the experiment made, the form and habits of the two birds being very similar.

The paucity of the account here given will I trust be a sufficient hint to those who may be favourably situated for observing the habits of this species, that by transmitting their observations either to myself or to any scientific journal, they would be promoting the cause of science, and adding to the stock of human knowledge.

The sexes are readily distinguished by the marked difference in their plumage; both are crested, but the crest of the male is a rich scarlet, while that of the female is grey.

The male has the forehead, crest and cheeks fine scarlet, the remainder of the plumage dark slate-grey; all the feathers, with the exception of the primaries, secondaries and tail, narrowly margined with greyish white—decided and distinct on the upper, but much fainter on the under surface; irides blackish brown; bill light horn-colour; feet mealy black.

The general plumage of the female is dark slate-colour, the feathers of the back of the neck and back slightly margined with pale grey, the remainder of the upper surface crossed with irregular bars of greyish white; the wings have also a sulphurous hue, as if powdered with sulphur; the feathers of the under surface are margined with sulphur-yellow and dull red, changing into dull yellow on the under tail-coverts.

The Plate represents a male and a female of the natural size.

POLYTELIS BARRABANDI.

J. Gould and H.C. Richter del et lith. Hullmandel & Walton Imp.

POLYTELIS BARRABANDI, Wagl.

Barraband’s Parrakeet.

Psittacus Barrabandi, Swains. Zool. Ill., 1st Ser., pl. 59.

Palæornis Barrabandi, Vig. in Zool. Journ., vol. ii. p. 56.—Vig. and Horsf. in Linn. Trans., vol. xv. p. 287.

Polytelis Barrabandi, Wagl. Mon. Psitt. in Abhand., pp. 489 and 519.—Gould in Syn. Birds of Australia, Part IV.

Scarlet-breasted Parrot, Lath. Gen. Syn., vol. ii. p. 121.—Ib. Gen. Hist., vol. ii. p. 121.

Palæornis rosaceus, Vig. in Lear’s Ill. Psitt., pl. 30, female.

Psittacus sagittifer Barrabandi, Bourj. de St. Hil., Supp. to Le Vaill. Hist. Nat. des Perr., pl. 4.

Green-leek of the Colonists of New South Wales.

In the great family of Parrots, few species are more elegant in form or more exquisitely coloured than the present, which is a native of New South Wales, where it is more abundant in the interior than in the districts near the coast. It is said sometimes to occur in the Illawarra district, but I did not succeed in finding it there myself. Living individuals are frequently brought down to Sydney by the draymen of the Argyle county, where it appears to be a common species. When we know more of its history I expect it will be found to inhabit similar localities, and enjoy a similar range to the P. melanura, and that the two species as closely assimilate in their habits and economy as they do in form. It is somewhat singular, that the female of this bird, as well as that of the preceding species, should have been described by the late Mr. Vigors as distinct; fine figures of both form part of Mr. Lear’s “Illustrations of the Psittacidæ”; the singular curve in the outer tail-feathers in Mr. Lear’s drawing of the female arises from their being newly moulted feathers, which in this species have always a tendency to curve outwards, at least such is the case with individuals kept in confinement.

From the length of its wings and the general contour of its body, we may feel assured that, like the P. melanura, its power of flight is very great, and that it is doubtless enabled to pass from one part of the continent to another whenever nature prompts it to make the passage.

The female, although equally graceful in form as her mate, is nevertheless much inferior to him in the colouring of her plumage; the green of the wings and body being less brilliant, and the rich colouring of the crown and cheeks being entirely wanting; a similar kind of plumage also characterizes the male during the first year.

The male has the forehead, cheeks and throat rich gamboge-yellow; immediately beneath the yellow of the throat a crescent of scarlet; back of the head, all the upper and under surface grass-green; primaries, secondaries, spurious wing and tail dark blue tinged with green; thighs in some scarlet, in others grass-green; irides orange-yellow; bill rich red; feet brown.

The female has the face dull greenish blue; chest dull rose-colour; thighs scarlet; the remainder of the body grass-green; primaries bluish green; central tail-feathers uniform green, the remainder bluish green, with the inner webs for their entire length fine rosy red; irides brown; bill pale reddish orange; feet dark brown.

The Plate represents the two sexes of the natural size.

POLYTELIS MELANURA.

J. Gould and H.C. Richter del et lith. Hullmandel & Walton Imp.

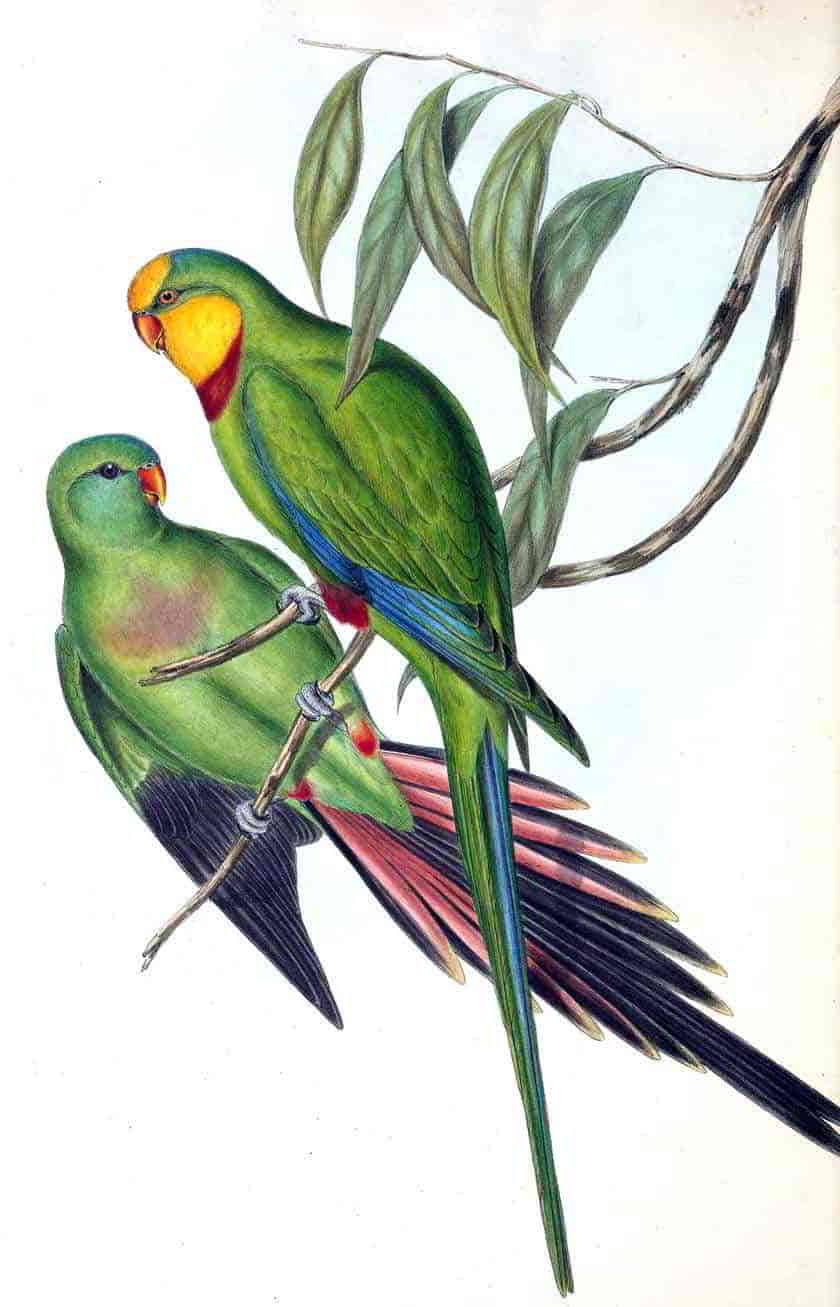

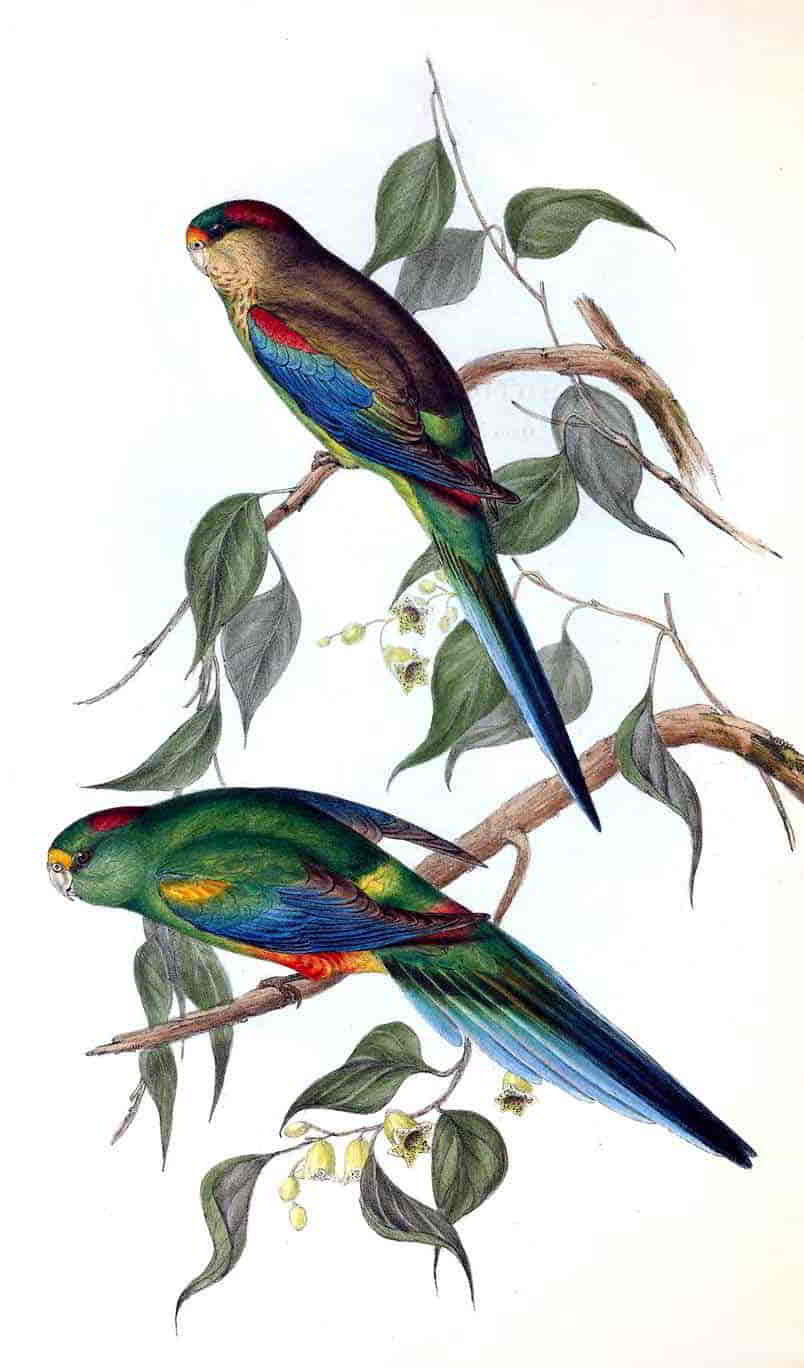

POLYTELIS MELANURA.

Black-tailed Parrakeet.

Palæornis melanura, Vig. in Lear’s Ill. Psitt., pl. 28, male.

—— anthopeplus, Vig. in Ib., pl. 29, female.

Polytelis melanura, Gould in Syn. Birds of Australia, Part IV.

Woȕk-un-ga, Aborigines of the mountain districts of Western Australia.

Jul-̏u-up, Aborigines of King George’s Sound.

Mountain Parrot, Colonists of Western Australia.

So little is known of the habits and economy of this beautiful Parrakeet, which has hitherto only been found on the southern portion of the continent of Australia, that the present paper must necessarily be brief. It is strictly an inhabitant of the interior, over which it doubtless ranges widely. Captain Sturt found it on the banks of the Murray, and has given a figure of it in the narrative of his journeys into the interior; His Excellency Governor Grey procured it in the dense scrub to the north-west of Adelaide, and Mr. Gilbert encountered it in the white-gum forests of the Swan River settlement. The extent of its range northward must be left for future researches to determine. Captain Sturt at page 188 of his second volume says, “I believe I have already mentioned that shortly after we first entered the Murray, flocks of a new Paroquet passed over our heads, apparently emigrating to the N.W. They always kept too high to be fired at, but on our return, hereabouts, we succeeded in killing one. It made a good addition to our scanty stock of subjects of natural history.” I believe I am indebted to the kindness and liberality of Captain Sturt for the identical specimen alluded to, a very fine one having been presented to me by him when I visited South Australia.

While flying it utters a loud harsh scream, which is changed into a chattering discordant tone upon alighting on the branches.

Mr. Gilbert remarks, that in Western Australia, except during the breeding-season, it is always to be met with in small families of from nine to twelve in number, feeding on seeds, buds of flowers and honey gathered from the white-gum-tree. Its flight, as indicated by its form, is rapid in the extreme. On reference to the synonyms given above, it will be seen that the late Mr. Vigors characterized the female as a distinct species from the male. Both sexes are beautifully figured in Mr. Lear’s “Illustrations of the Psittacidæ,” on reference to which and to the accompanying Plate, it will be seen that they differ very considerably in colour, the rich jonquil-yellow of the male giving place to dull yellowish green in the opposite sex, whence doubtless arose Mr. Vigors’s error.

The male has the head, neck, shoulders, rump, and all the under surface beautiful jonquil-yellow; upper part of the back and scapularies olive; primaries and tail deep blue; several of the greater wing-coverts dull scarlet, forming a conspicuous mark on the centre of the wing; irides bright red; bill scarlet; feet ash-grey.

The female has the head, sides of the face, back of the neck, upper part of the back and scapulars dull olive-green; throat, all the under surface, rump and wing-coverts yellowish green, the latter passing into deep green on the centre of the shoulder; primaries, some of the secondaries, and the spurious wing deep blue-black, margined externally with yellowish green; the remainder of the secondaries and a few of the greater coverts deep red; two centre tail-feathers deep green, the remainder green at the base, passing into black on the inner webs; the five lateral feathers on each side margined on their inner webs and tipped with rosy red, which is broadest and most conspicuous on the two outer feathers; bill scarlet; feet ash-grey.

The Plate represents the two sexes of the natural size.

APROSMICTUS SCAPULATUS.

J. Gould and H.C. Richter del. C. Hullmandel Imp.

APROSMICTUS SCAPULATUS.

King Lory.

Psittacus scapulatus, Bechst.: Kuhl, Nova Acta, p. 56.—Shaw, Gen. Zool., vol. viii. p. 407. pl. 55.

Psittacus Tabuensis, var. β, Lath. Ind. Orn., p. 88.

La Grande Perruche à collier et croupion bleu, Le Vaill. Hist, des Perr., pls. 55 and 56.

Tabuan Parrot, White’s Journ., pl. in p. 168 male, in p. 169 female.—Phill. Bot. Bay, pl. in p. 153.—Lath. Gen. Syn. Supp., vol. ii. p. 81.

Platycercus scapulatus, Vig. and Horsf. in Linn. Trans., vol. xv. p. 284.—Wagl. Mon. Psitt. in Abhand., tom. i. pp. 492 and 537.—Steph. Cont. of Shaw’s Gen. Zool., vol. xiv. p. 122.

Psittacus cyanopygius, Vieill., 2nde Edit. du Nouv. Dict. d’Hist. Nat., tom. xxv. p. 339.—Ibid. Gal. des Ois. Supp., pls. of male and female.

Scarlet and Green Parrot, Lath. Gen. Hist., vol. ii. p. 116.

Platycercus scapularis, Swains. Zool. Ill., 2nd Ser. pl. 26.—Less. Traité d’Orn., p. 207.

Aprosmictus scapulatus, Gould in Proc. of Zool. Soc., August 9, 1842.

Wellat, Aborigines of New South Wales.

This very showy and noble species appears to be extremely local in its habitat; if I remember rightly, I have not seen it from any other portion of Australia than New South Wales, in which country it appears to be almost exclusively confined to the brushes, particularly such as are low and humid, and where the large Casuarinæ grow in the greatest profusion. All the brushes stretching along the southern and eastern coast appear to be equally favoured with its presence, as it there finds a plentiful supply of food, consisting of seeds, fruits and berries. At the period when the Indian corn is becoming ripe it leaves its umbrageous abode and sallies forth in vast flocks, which commit great devastation on the ripening grain. It is rather a dull and inactive species compared with the members of the restricted genus Platycercus; it flies much more heavily, and is very different in its disposition, for although it soon becomes habituated to confinement, it is less easily tamed and much less confiding and familiar; the great beauty of the male, however, somewhat compensates for this unpleasant trait, and consequently it is highly prized as a cage-bird.

I was never so fortunate as to find the nest of this species, neither could I gather any information respecting this part of the bird’s economy; and I am inclined to look with suspicion on the account given by Mr. Caley, as recorded in the Linnean Transactions, which in my opinion must have reference to the eggs of some other bird.

When fully adult the sexes differ very considerably in the colouring of the plumage, as will be seen by the following descriptions.

The male has the head, neck and all the under surface scarlet; back and wings green, the inner webs of the primaries and secondaries being black; along the scapularies a broad line of pale verdigris-green; a line bounding the scarlet at the back of the neck, the rump and upper tail-coverts rich deep blue; tail black; pupil large and black; irides narrow and yellow; bill scarlet; legs mealy brown.

The female has the head and all the upper surface green; throat and chest green tinged with red; abdomen and under tail-coverts scarlet; rump dull blue; two centre tail-feathers green; the remainder green, passing into bluish black; and with a rose-coloured spot at the extremity on the under surface.

The young male for the first two years resembles the female, which is doubtless the cause why so few birds are seen in the bright red dress, compared with those having a green head and chest.

The Plate represents the two sexes of the natural size.

APROSMICTUS ERYTHROPTERUS.

J. Gould and H.C. Richter delt. C. Hullmandel Imp.

APROSMICTUS ERYTHROPTERUS.

Red-winged Lory.

Psittacus erythropterus, Gmel. Syst., vol. i. p. 343.—Kuhl, Nova Acta, vol. x. p. 53.—Quoy et Gaim. Zool. de la Voy. autour du Monde, pl. 27.—Lath. Ind. Orn., vol. i. p. 126.

Psittacus melanotus, Shaw, Nat. Misc., pl. 653.—Ib. Gen. Zool., vol. viii. p. 467.

Crimson-winged Parrot, Lath. Gen. Syn., vol. i. p. 299; and Supp. p. 60.—Ib. Gen. Hist., vol. ii. p. 253.

Platycercus erythropterus, Vig. and Horsf. in Linn. Trans., vol. xv. p. 284.—Less. Traité d’Orn., p. 208.—Wagl. Mon. Psitt. in Abhand., tom. i. pp. 492 and 536.—Steph. Cont. of Shaw’s Gen. Zool., vol. xiv. p. 123.

Aprosmictus erythropterus, Gould in Proc. of Zool. Soc., August 9, 1842.

This beautiful Lory is very widely distributed over the greater portion of the continent of Australia, and its range also extends to New Guinea and Timor; I must not, however, fail to remark, that specimens from the latter countries, as well as those from Port Essington, are smaller in all their admeasurements than those from the southern and eastern portions of Australia; no difference whatever exists in the markings or colouring of the individuals from all these various localities, I am therefore induced to consider them as so many races of the same bird, rather than as distinct species.

In Australia, the Red-winged Lory, so far as my observation has enabled me to judge, is as exclusively an inhabitant of the interior of the country as its near ally the King Lory is a denizen of the thick brushes which extend along the coast, both, as is always the case, being beautifully adapted to the character of country they are respectively destined to inhabit. The extensive belts of Acacia pendula which stretch over and diversify the arid plains of the great Australian basin, are tenanted with thousands of this bird, besides numerous other species, roaming about either in small companies of six or eight, or in flocks of a much greater number. It is beyond the power of my pen to describe or give a just idea of the extreme beauty of the appearance of the Red-winged Lory when seen among the silvery branches of the Acacia, particularly when the flocks comprise a large number of adult males, the gorgeous scarlet of whose shoulders offers so striking a contrast to the surrounding objects. It is rather thinly dispersed among the trees skirting the rivers which intersect the Liverpool Plains, but from thence towards the interior it increases in number, and probably extends over the whole of the interior, for it is as abundant at Port Essington on the north coast as it is on the southern: I have also received it from South Australia and the north-west coast, but not as yet from Swan River. In its actions and disposition it has much of the character of the King Lory, being morose and indocile: as it is naturally shy and wary, it is much more difficult of approach than the generality of the Parrots; and although the contrary is sometimes the case, it seldom becomes tame or familiar in captivity.

Its powers of flight are fully adequate and in every way adapted to the extensive plains it is destined to inhabit, enabling it readily to pass, frequently at a great height in the air, from one part of the plain to another. Its flight is, however, performed with a motion of the wings totally different from that of any other member of the great family of Psittacidæ I have seen, and has frequently reminded me of the heavy flapping manner of the Pewit, except that the flapping motion was even slower and more laboured, like that of the Terns. It has a loud screeching piercing cry, which it frequently utters during flight.

Its food consists of berries, the fruits of a species of Loranthus, and the pollen of flowers, to which is added a species of scaly bug-like insect, which infests the branches of its favourite trees; in all probability small caterpillars also form a part, as I have found them in the crops of several of the Platycerci.

It breeds in the holes of the large Eucalypti growing on the banks of rivers; the eggs, which are white, being four or five in number, about an inch and an eighth long by seven-eighths broad.

The sexes, as will be seen in the accompanying Plate, differ very considerably in the colouring of their plumage; the young males during the first two years cannot be distinguished from the female, except by dissection.

The male has the head and back of the neck verditer green; throat, all the under surface, edge of the shoulder and upper tail-coverts bright yellowish green; back black; rump lazuline blue; wing-coverts deep rich crimson-red; scapularies dark green, tipped with black; primaries black at the base, with the external webs and the apical portion of the inner webs deep green; secondaries black, edged with deep green, and one or two with a tinge of red at the tip; tail green above, passing into yellow at the tip, the extreme end fringed with pink; under surface of the tail black, tipped with yellow and pink as above; irides reddish orange in some, scarlet in others; bill rich orange-scarlet; feet olive-brown.

The female has the head and upper surface dull green; under surface dull yellowish green; a few of the wing-coverts crimson-red, forming a stripe down the wing; rump pale verditer blue; tail-feathers more largely tipped with pink than in the male; irides olive-brown; bill light horn-colour.

The Plate represents the two sexes of the natural size.

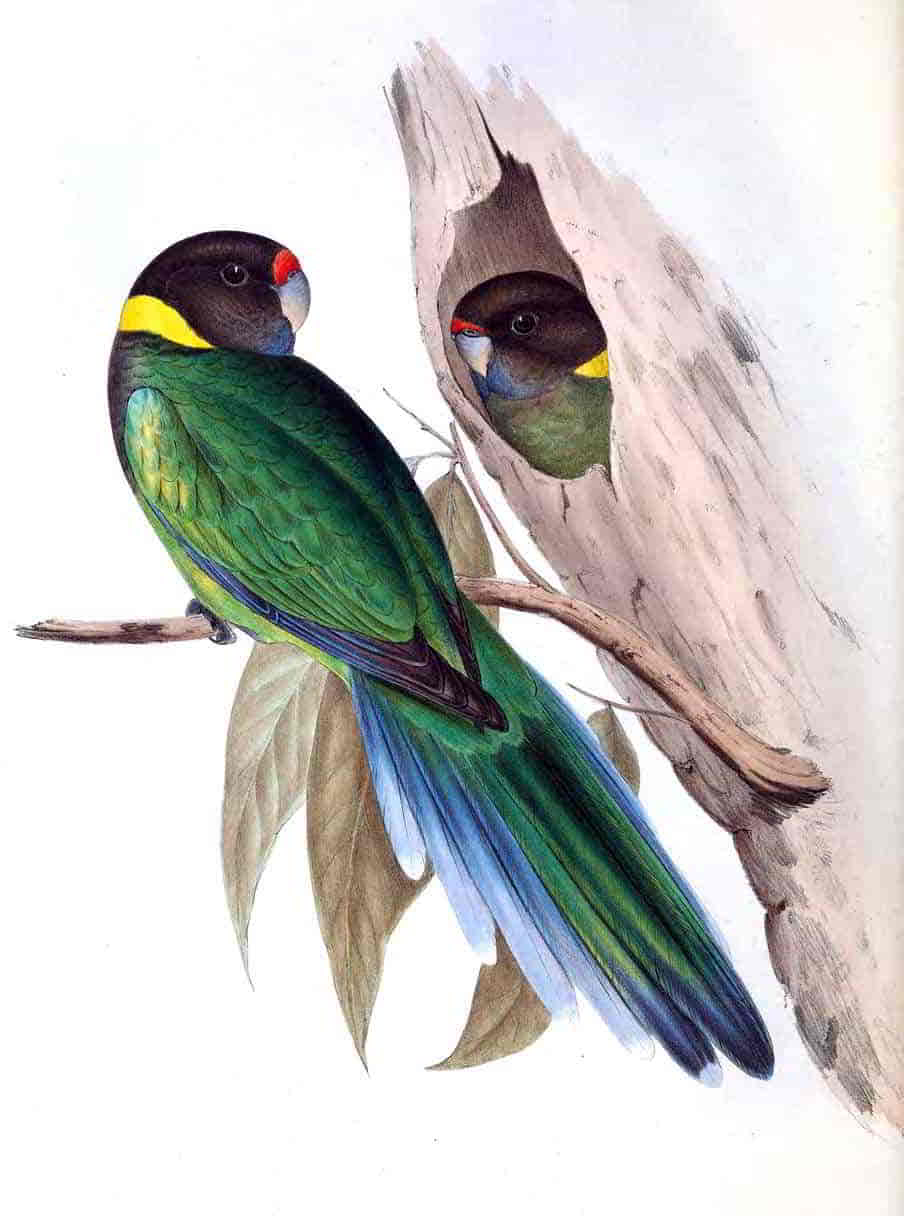

PLATYCERCUS SEMITORQUATUS.

J. Gould and H.C. Richter del et lith. C. Hullmandel Imp.

PLATYCERCUS SEMITORQUATUS, Quoy and Gaim.

Yellow-collared Parrakeet.

Psittacus semitorquatus, Quoy and Gaim.

Dȍw-arn, Aborigines of the lowland districts of Western Australia.

Dȕm-ul-uk, Aborigines of the mountain districts of Western Australia.

Twenty-eight Parrakeet, Colonists of Swan River.

This very noble species of Platycercus is abundantly dispersed over the greater portion of Western Australia, where it inhabits almost every variety of situation, sometimes searching for food upon the ground like the rest of its congeners, and at others on the trees; its chief food being either grass-seeds or the hard stoned fruits and seeds peculiar to the trees of the country in which it lives. It is equally as abundant at King George’s Sound as it is at Swan River; I have not been so fortunate as to obtain any precise information as to the extent of its range over the continent, the only parts of the country from which I have received specimens being the two localities mentioned above.

This fine bird, like the rest of the true Platycerci, is entirely destitute of the os furcatum; hence, like them, its powers of flight are very limited; on the other hand it runs quickly over the surface of the ground, as may be seen by all who have observed the bird in a cage, to which it is often consigned and sent to this country as an ornament for the aviary, which it graces, both by its large size and the richly contrasted colouring of its plumage. While on the wing its motion is tolerably rapid, and it often utters a note, which from its resemblance to those words has procured for it the appellation of “twenty-eight” Parrakeet from the colonists; the last word or note being sometimes repeated five or six times in succession.

It begins breeding in the latter part of September or beginning of October, making no nest, but depositing its eggs in a hole in either a gum- or mahogany-tree, on the soft black dust collected at the bottom; they are from seven to nine in number and of a pure white.

The sexes may be distinguished by the much smaller size of the female, and by her markings being much less distinct.

Forehead crossed by a narrow band of crimson; head blackish brown, passing into blue on the cheeks; back of the neck encircled by a band of bright yellow; back and upper surface generally deep grass-green, passing into pale green on the shoulders; primaries and spurious wing blackish brown, the external webs of each feather deep blue; two centre tail-feathers deep grass-green, the next on each side the same passing into blue and ending in bluish white at the tip; the lateral feathers green at the base passing into blue, which gradually fades into bluish white at the tip; chest green; under surface light green; irides dark brown; bill light horn-colour, becoming of a lead-colour on the front of the upper mandible; legs and feet dark brown.

The Plate represents the birds of the natural size.

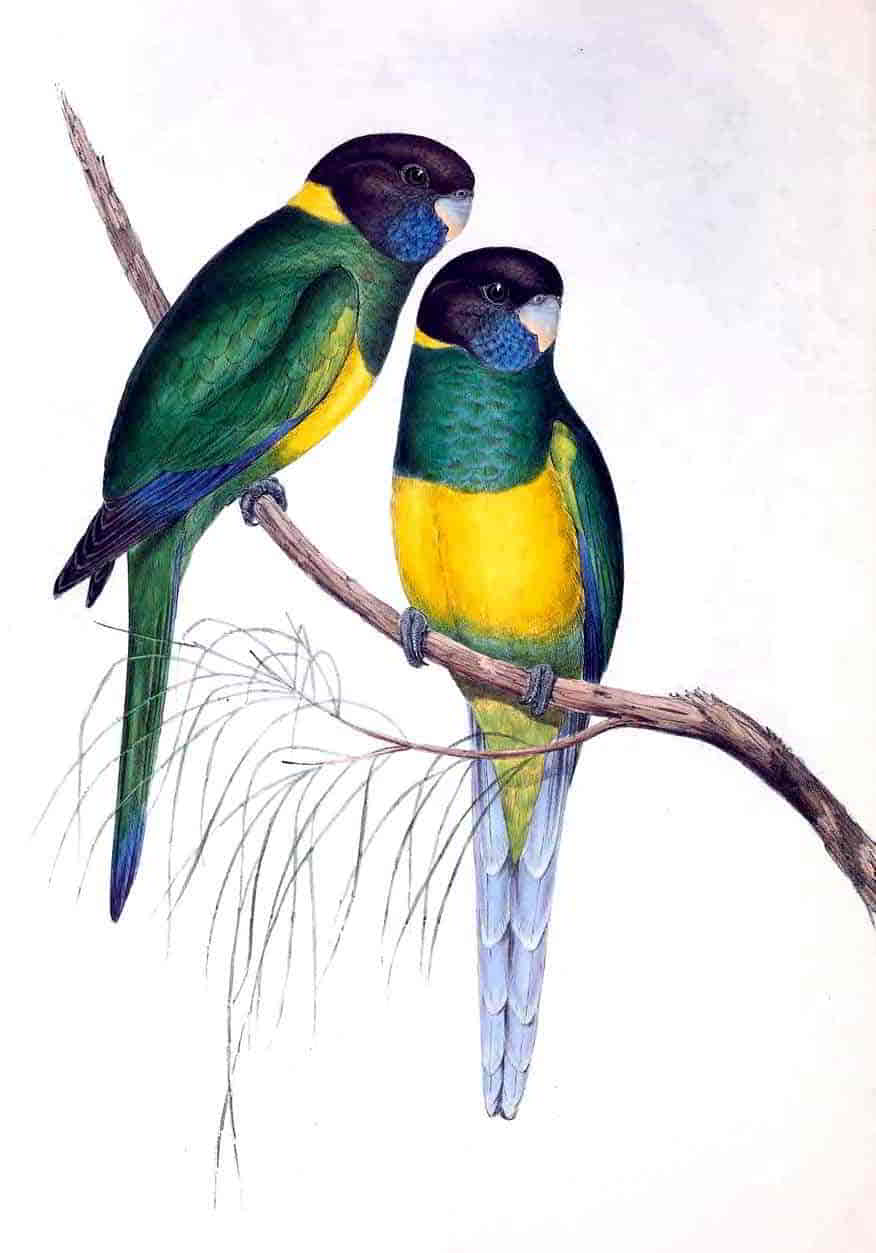

PLATYCERCUS BAUERI: Vig. & Horsf.

J. Gould and H.C. Richter del et lith. C. Hullmandel Imp.

PLATYCERCUS BAUERI, Vig. and Horsf.

Bauer’s Parrakeet.

Psittacus Baueri, Temm. in Linn. Trans., vol. xiii. p. 118.—Donovan’s Nat. Repos., pl 64.

Psittacus cyanomelus, Kuhl. Consp. Psitt, in Nov. Act., vol. x. p. 53.

Bauer’s Parrot, Lath. Gen. Hist., vol. ii. p. 120.

Platycercus Baueri, Vig. and Horsf. in Linn. Trans., vol. xv. p. 283.—Lear’s Ill. Psitt. pl. 17.—Steph. Cont. of Shaw’s Gen. Zool., vol. xiv. p. 121.

Platycercus zonarius, Wagl. Mon. Psitt. in Abhand., p. 538.

Psittacus zonarius, Shaw’s Nat. Misc., pl. 657.—Kuhl, Consp. Psitt. in Nov. Act., tom. i.

Psittacus viridis, Shaw’s Gen. Zool., vol. viii. p. 465.

Nanodes? zonarius, Steph. Cont. of Shaw’s Gen. Zool., vol. xiv. p. 119.