.

PRIMITIVE MAN.

PRIMITIVE MAN.

By LOUIS FIGUIER.

ILLUSTRATED WITH THIRTY SCENES OF PRIMITIVE LIFE, AND

TWO HUNDRED AND THIRTY-THREE FIGURES OF OBJECTS

BELONGING TO PRE-HISTORIC AGES.

LONDON:

CHAPMAN AND HALL, 193, PICCADILLY.

1870.

PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH EDITION.

The Editor of the English translation of 'L'Homme Primitif,' has not deemed it necessary to reproduce the original Preface, in which M. Figuier states his purpose in offering a new work on pre-historic archæology to the French public, already acquainted in translation with the works on the subject by Sir Charles Lyell and Sir John Lubbock. Now that the book has taken its position in France, it is only needful to point out its claims to the attention of English readers.

The important art of placing scientific knowledge, and especially new discoveries and topics of present controversy, within easy reach of educated readers not versed in their strictly technical details, is one which has for years been carried to remarkable perfection in France, in no small measure through the labours and example of M. Figuier himself. The present volume, one of his series, takes up the subject of Pre-historic Man, beginning with the remotely ancient stages of human life belonging to the Drift-Beds, Bone-Caves, and Shell-Heaps, passing on through the higher levels of the Stone Age, through the succeeding Bronze Age, and into those lower ranges of the Iron Age in which civilisation, raised to a comparatively high development, passes from the hands of the antiquary into those of the historian. The Author's object has been to give within the limits of a volume, and dispensing with the fatiguing enumeration of details required in special memoirs, an outline sufficient to afford a reasonable working acquaintance with the facts and arguments of the science to such as cannot pursue it further, and to serve as a starting-ground for those who will follow it up in the more minute researches of Nilsson, Keller, Lartet, Christy, Lubbock, Mortillet, Desor, Troyon, Gastaldi, and others.

The value of the work to English archæologists, however, is not merely that of a clear popular manual; pre-historic archæology, worked as it has been in several countries, takes in each its proper local colour, and brings forward its proper local evidence. It is true that much of its material is used as common property by scientific men at large. But, for instance, where an English writer in describing the ancient cave-men would dwell especially on the relics from the caves of Devon and Somerset as worked by Falconer and Pengelly, a French writer would take his data more amply from the explorations of caves of the south of France by De Vibraye, Garrigou, and Filhol—where the English teacher would select his specimens from the Christy or the Blackmore Museum, the French teacher would have recourse to the Musée de Saint-Germain. Thus far, the English student has in Figuier's 'Primitive Man' not a work simply incorporated from familiar materials, but to a great extent bringing forward evidence not readily accessible, or quite new to him.

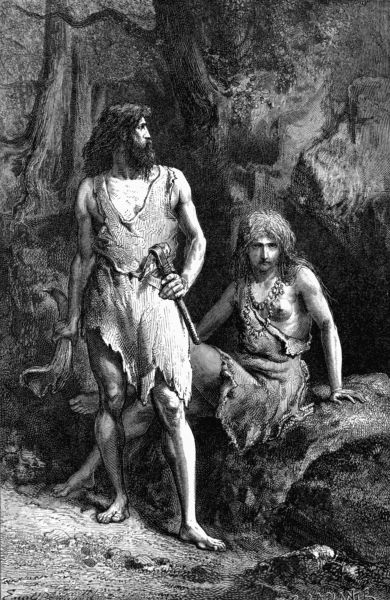

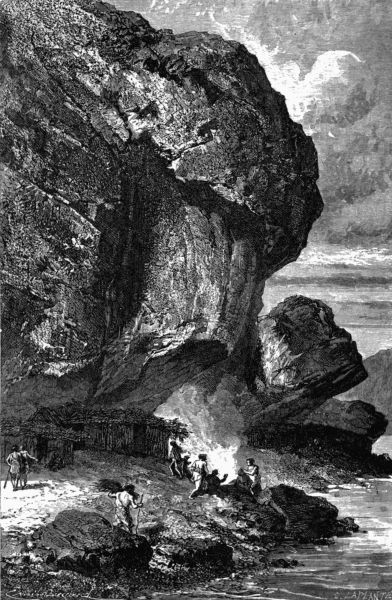

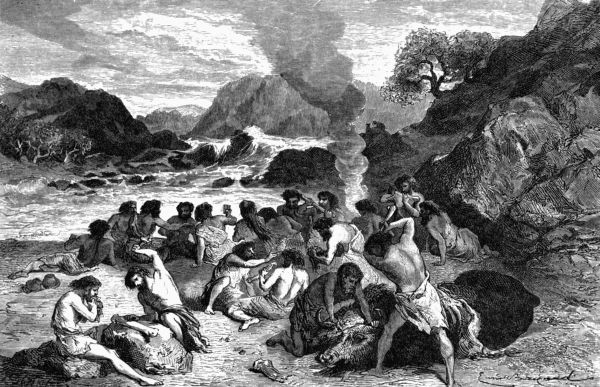

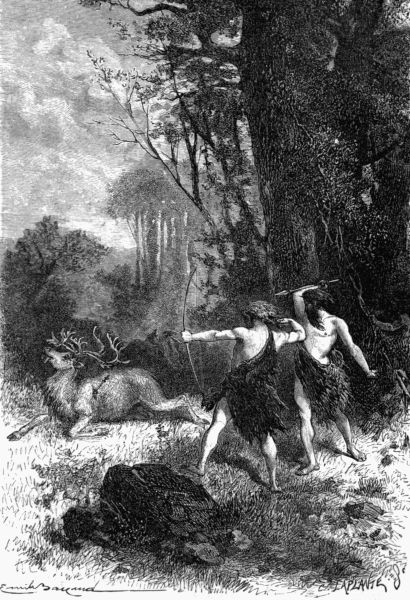

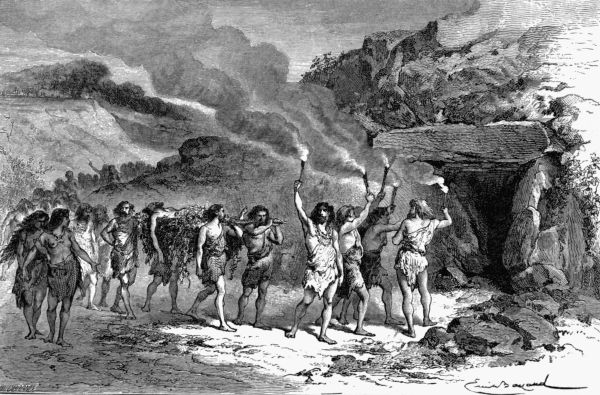

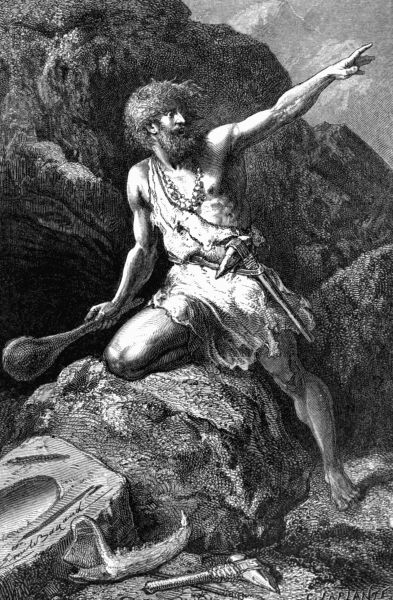

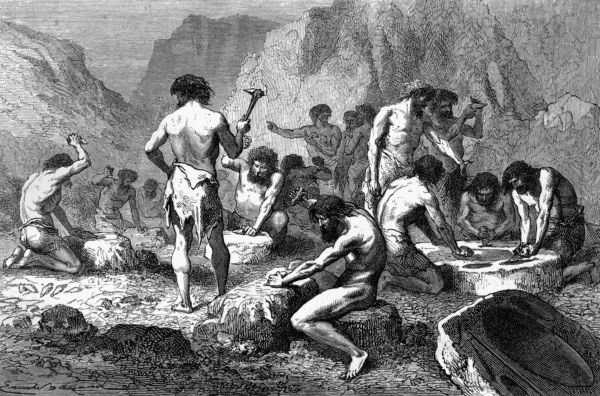

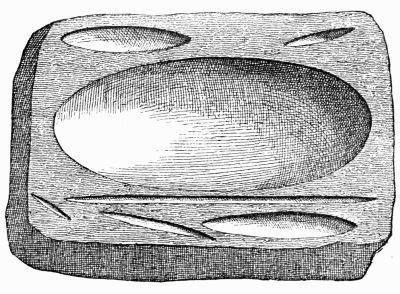

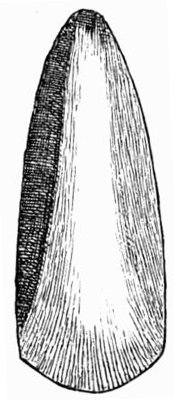

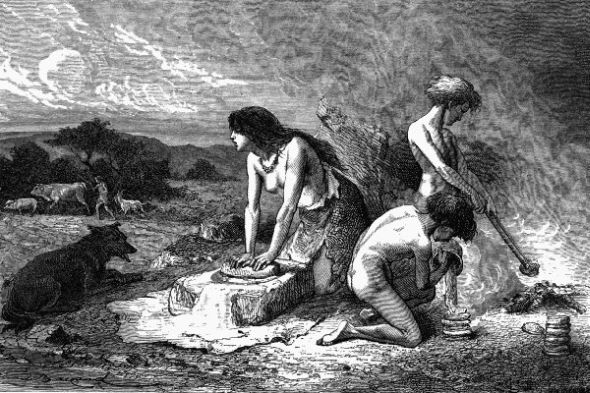

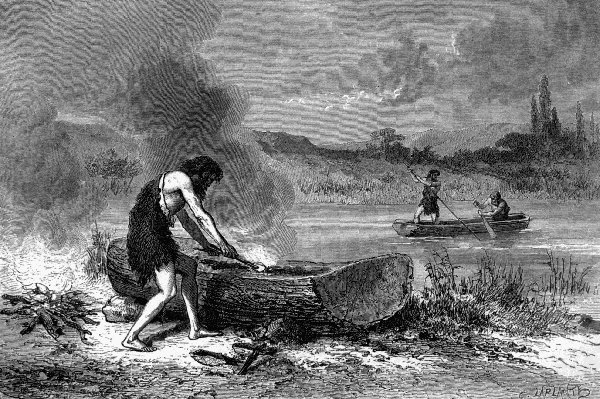

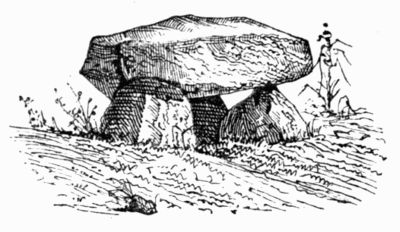

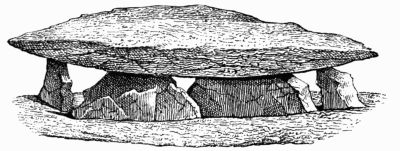

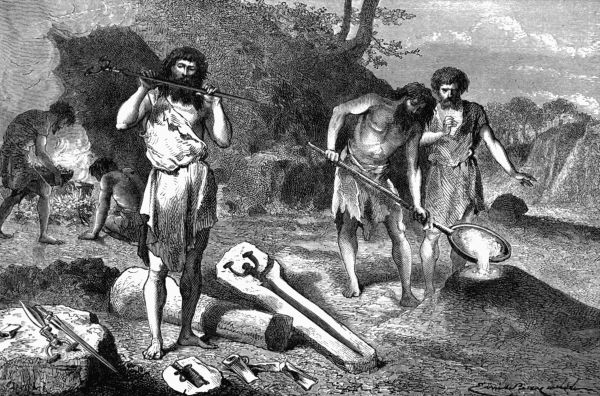

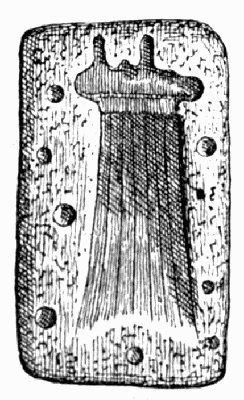

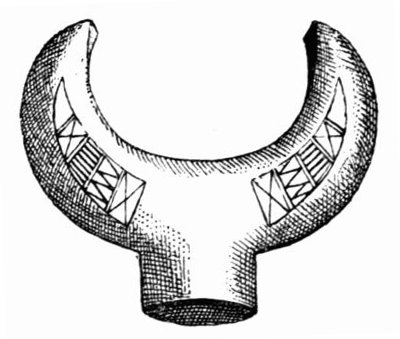

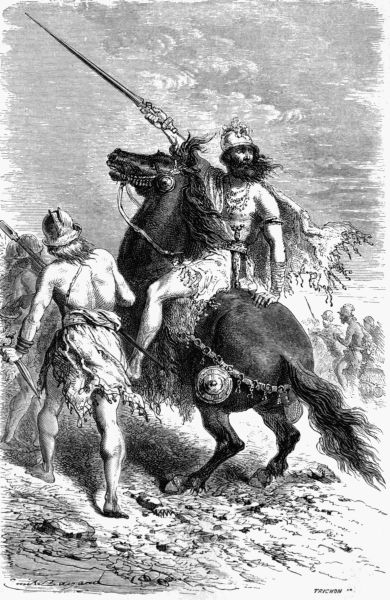

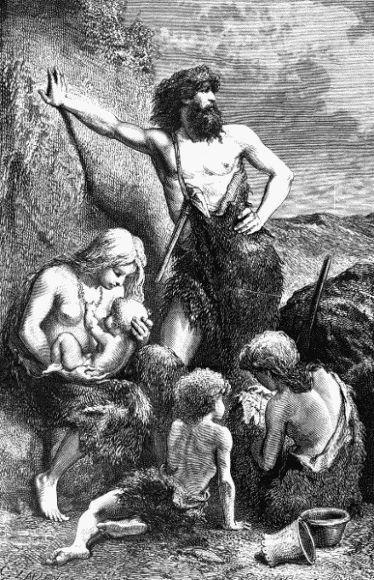

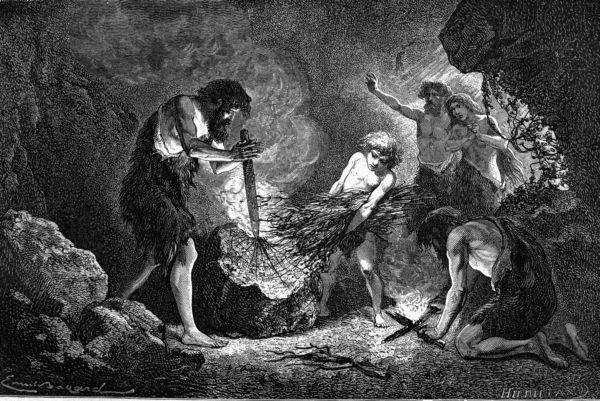

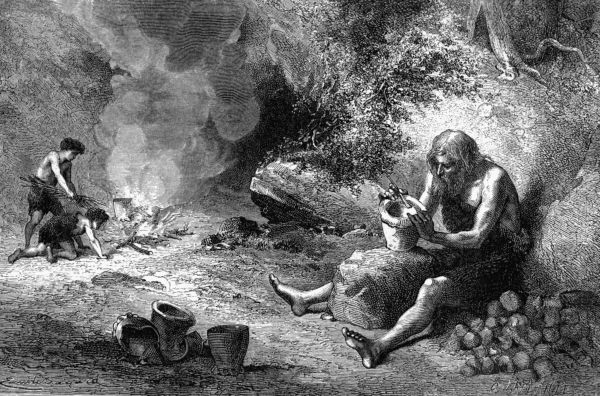

Some corrections and alterations have been made in the English edition. The illustrations are those of the original work; the facsimiles of pre-historic objects have been in great part drawn expressly for it, and contribute to its strictly scientific value; the page illustrations representing scenes of primitive life, which are by another hand, may seem somewhat fanciful, yet, setting aside the Raffaelesque idealism of their style, it will be found on examination that they are in the main justified by that soundest evidence, the actual discovery of the objects of which they represent the use.

The solid distinctness of this evidence from actual relics of pre-historic life is one of the reasons which have contributed to the extraordinary interest which pre-historic archæology has excited in an age averse to vague speculation, but singularly appreciative of arguments conducted by strict reasoning on facts. The study of this modern science has supplied a fundamental element to the general theory of civilisation, while, as has been the case with geology, its bearing on various points of theological criticism has at once conduced to its active investigation, and drawn to it the most eager popular attention. Thus, in bringing forward a new work on 'Primitive Man,' there is happily no need of insisting on the importance of its subject-matter, or of attempting to force unappreciated knowledge on an unwilling public. It is only necessary to attest its filling an open place in the literature of pre-historic archæology.

E. B. T.

CONTENTS.

PAGE

| INTRODUCTION. | 1 |

THE STONE AGE.

I.

The Epoch of Extinct Species of Animals; or, of the Great Bear and Mammoth.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| The earliest Men—The Type of Man in the Epoch of Animals of extinct Species—Origin of Man—Refutation of the Theory which derives the Human Species from the Ape | 25 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

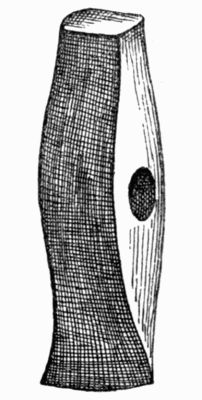

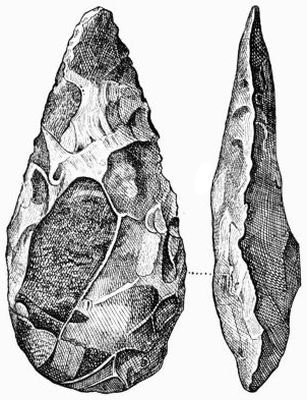

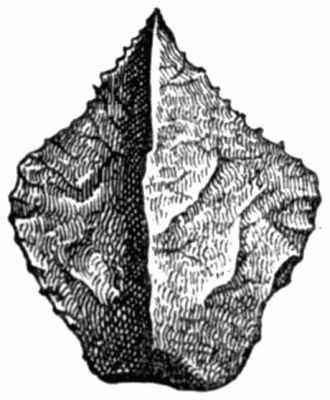

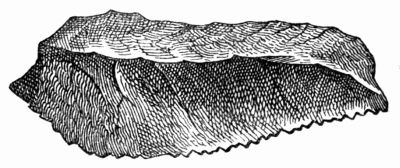

| Man in the Condition of Savage Life during the Quaternary Epoch—The Glacial Period, and its Ravages on the Primitive Inhabitants of the Globe—Man in Conflict with the Animals of the Quaternary Epoch—The Discovery of Fire—The Weapons of Primitive Man—Varieties of Flint Hatchets—Manufacture of the earliest Pottery—Ornamental objects at the Epoch of the Great Bear and the Mammoth | 39 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| The Man of the Great Bear and Mammoth Epoch lived in Caverns—Bone Caverns in the Quaternary Rock during the Great Bear and Mammoth Epoch—Mode of Formation of these Caverns—Their Division into several Classes—Implements of Flint, Bone, and Reindeer-horn, found in these Caverns—The Burial Place at Aurignac—Its probable Age—Customs which it reveals—Funeral Banquets during the Great Bear and Mammoth Epoch | 56 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Other Caves of the Epoch of the Great Bear and Mammoth—Type of the Human Race during the Epochs of the Great Bear and the Reindeer—The Skulls from the Caves of Engis and Neanderthal | 72 |

II.

Epoch of the Reindeer; or, of Migrated Animals.

| CHAPTER I. | |

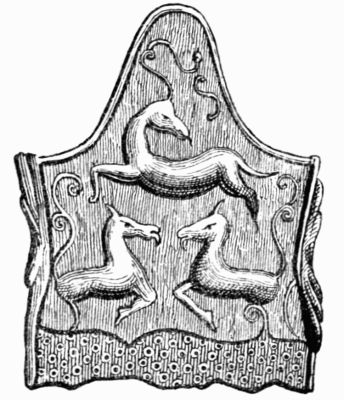

| Mankind during the Epoch of the Reindeer—Their Manners and Customs—Food—Garments—Weapons, Utensils, and Implements—Pottery—Ornaments—Primitive Arts—The principal Caverns—Type of the Human Race during the Epoch of the Reindeer | 85 |

III.

The Polished-stone Epoch; or, the Epoch of Tamed Animals.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| The European Deluge—The Dwelling-Place of Man during the Polished-stone Epoch—The Caves and Rock-Shelters still used as Dwelling-Places—Principal Caves belonging to the Polished-stone Epoch which have been explored up to the present time—The Food of Man during this Period | 125 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

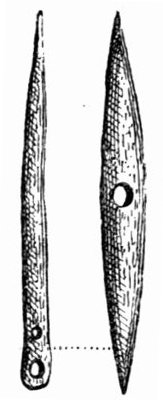

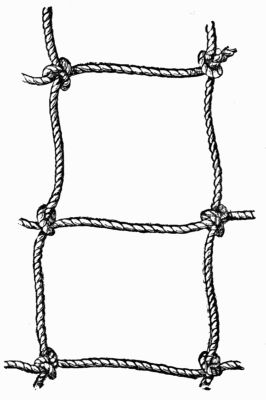

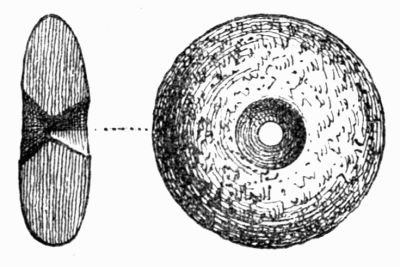

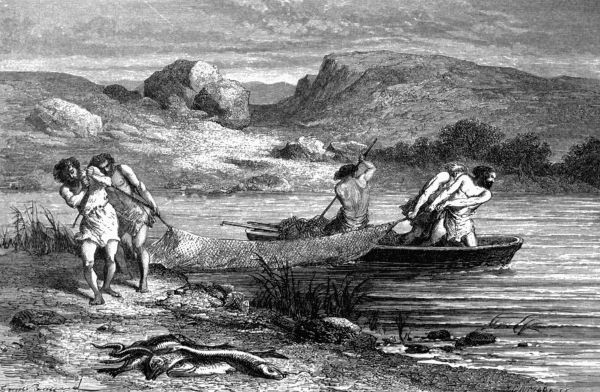

| The Kjoekken-Moeddings or "Kitchen-middens" of Denmark—Mode of Life of the Men living in Denmark during the Polished-stone Epoch—The Domestication of the Dog—The Art of Fishing during the Polished-stone Epoch—Fishing Nets—Weapons and Instruments of War—Type of the Human Race; the Borreby Skull | 129 |

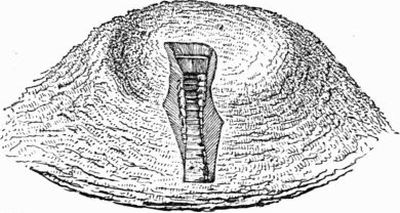

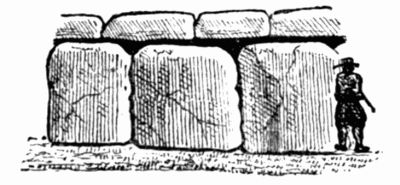

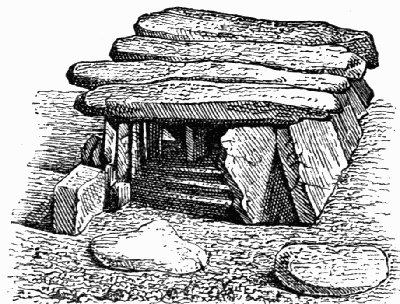

| CHAPTER III. | |

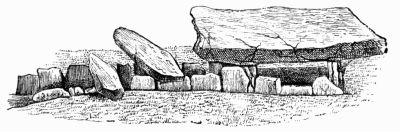

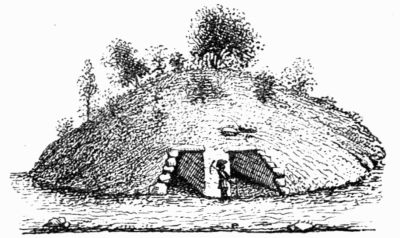

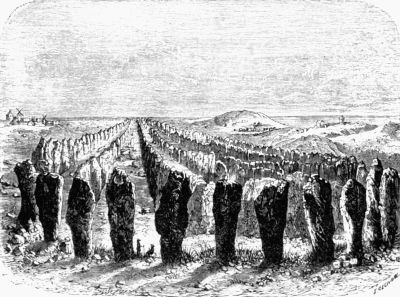

| Tombs and Mode of Interment during the Polished-stone Epoch—Tumuli and other Sepulchral Monuments formerly called Celtic—Labours of MM. Alexander Bertrand and Bonstetten—Funeral Customs | 184 |

THE AGE OF METALS.

I.

The Bronze Epoch.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| The Discovery of Metals—Various Reasons suggested for explaining the origin of Bronze in the West—The Invention of Bronze—A Foundry during the Bronze Epoch—Permanent and Itinerant Foundries existing during the Bronze Epoch—Did the Knowledge of Metals take its Rise in Europe owing to the Progress of Civilisation, or was it a Foreign Importation? | 205 |

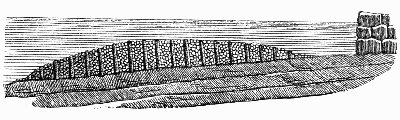

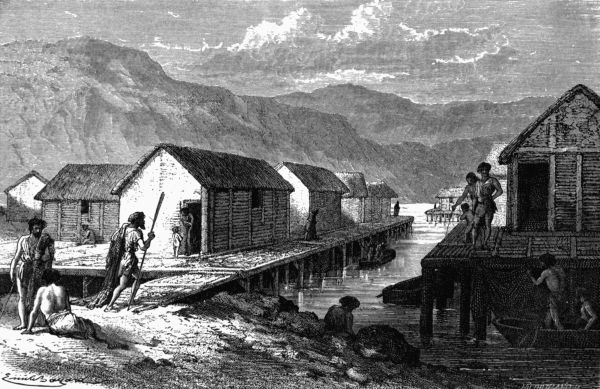

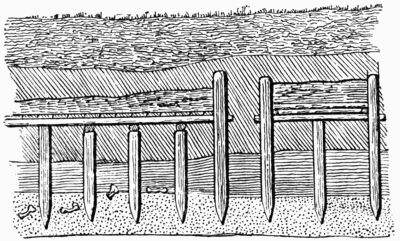

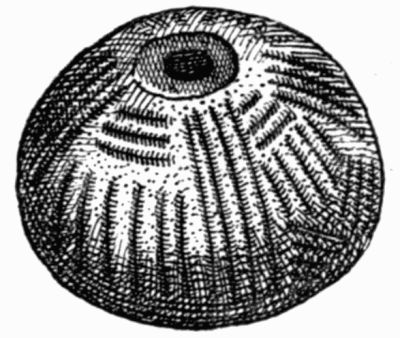

| CHAPTER II. | |

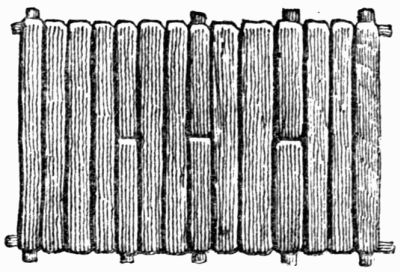

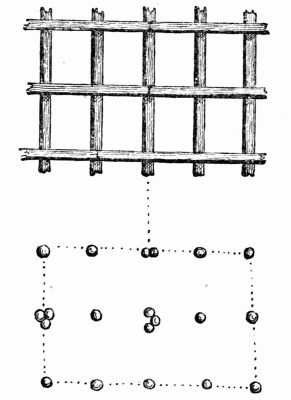

| The Sources of Information at our Disposal for reconstructing the History of the Bronze Epoch—The Lacustrine Settlements of Switzerland—Enumeration and Classification of them—Their Mode of Construction—Workmanship and Position of the Piles—Shape and Size of the Huts—Population—Instruments of Stone, Bone, and Stag's Horn—Pottery—Clothing—Food—Fauna—Domestic Animals | 215 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Lacustrine Habitations of Upper Italy, Bavaria, Carinthia and Carniola, Pomerania, France, and England—The Crannoges of Ireland | 227 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Palustrine Habitations or Marsh-Villages—Surveys made by MM. Strobel and Pigorini of the Terramares of Tuscany—The Terramares of Brazil | 232 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Weapons, Instruments, and Utensils contained in the various Lacustrine Settlements in Europe, enabling us to become acquainted with the Manners and Customs of Man during the Bronze Epoch | 240 |

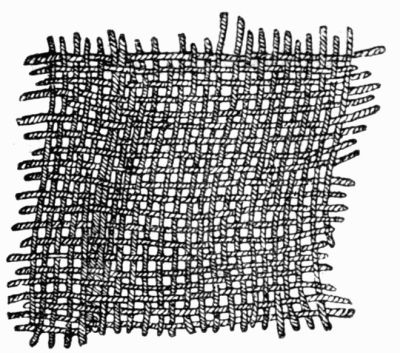

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Industrial Skill and Agriculture during the Bronze Epoch—The Invention of Glass—Invention of Weaving | 258 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

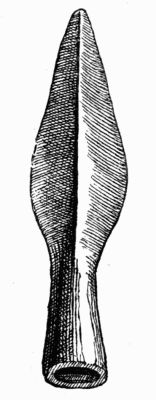

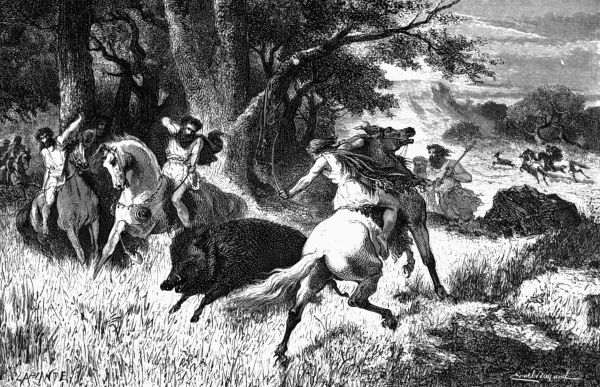

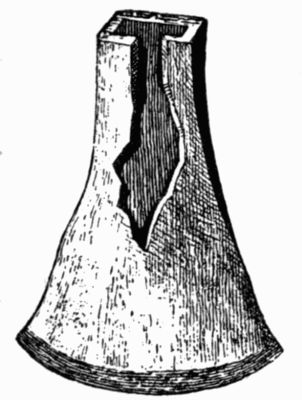

| The Art of War during the Bronze Epoch—Swords, Spears and Daggers—The Bronze Epoch in Scandinavia, in the British Isles, France, Switzerland and Italy—Did the Man of the Bronze Epoch entertain any religious or superstitious Belief? | 271 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Mode of Interment and Burial-places of the Bronze Epoch—Characteristics of the Human Race during the same Period | 284 |

II.

The Iron Epoch.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Essential Characteristics of the Iron Epoch—Preparation of Iron in Pre-historic Times—Discovery of Silver and Lead—Earthenware made on the Potter's Wheel—Invention of Coined Money | 297 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

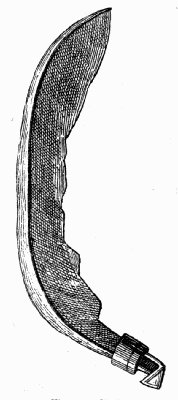

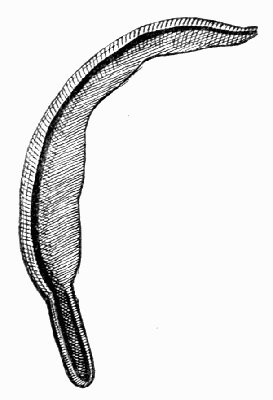

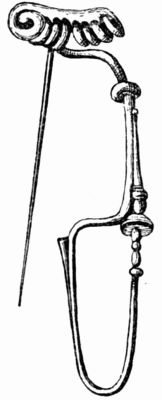

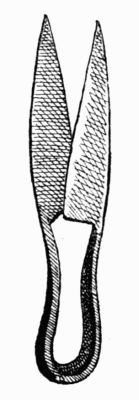

| Weapons—Tools, Instruments, Utensils, and Pottery—The Tombs of Hallstadt and the Plateau of La Somma—The Lake-Settlements of Switzerland—Human Sacrifices—Type of Man during the Iron Epoch—Commencement of the Historic Era | 312 |

| PRIMITIVE MAN IN AMERICA | 333 |

| CONCLUSION | 343 |

LIST OF PLATES.

PRIMITIVE MAN.

Forty years have scarcely elapsed since scientific men first began to attribute to the human race an antiquity more remote than that which is assigned to them by history and tradition. Down to a comparatively recent time, the appearance of primitive man was not dated back beyond a period of 6000 to 7000 years. This historical chronology was a little unsettled by the researches made among various eastern nations—the Chinese, the Egyptians, and the Indians. The savants who studied these ancient systems of civilisation found themselves unable to limit them to the 6000 years of the standard chronology, and extended back for some thousands of years the antiquity of the eastern races.

This idea, however, never made its way beyond the narrow circle of oriental scholars, and did nothing towards any alteration in the general opinion, which allowed only 6000 years since the creation of the human species.

This opinion was confirmed, and, to some extent, rendered sacred by an erroneous interpretation of Holy Writ. It was thought that the Old Testament stated that man was created 6000 years ago. Now, the fact is, nothing of the kind can be found in the Book of Genesis. It is only the commentators and the compilers of chronological systems who have put forward this date as that of the first appearance of the human race. M. Édouard Lartet, who was called, in 1869, to the chair of palæontology in the Museum of Natural History of Paris, reminds us, in the following passage taken from one of his elegant dissertations, that it is the chronologists alone who have propounded this idea, and that they have, in this respect, very wrongly interpreted the statements of the Bible:

"In Genesis," says M. Lartet, "no date can be found which sets a limit to the time at which primitive mankind may have made its first appearance. Chronologists, however, for fifteen centuries have been endeavouring to make Biblical facts fall in with the preconcerted arrangements of their systems. Thus, we find that more than 140 opinions have been brought forward as to the date of the creation alone, and that, between the varying extremes, there is a difference of 3194 years—a difference which only applies to the period between the commencement of the world and the birth of Jesus Christ. This disagreement turns chiefly on those portions of the interval which are in closest proximity to the creation.

"From the moment when it becomes a recognised fact that the origin of mankind is a question independent of all subordination to dogma, this question will assume its proper position as a scientific thesis, and will be accessible to any kind of discussion, and capable, in every point of view, of receiving the solution which best harmonises with the known facts and experimental demonstrations." [1]

Thus, we must not assume that the authority of Holy Writ is in any way questioned by those labours which aim at seeking the real epoch of man's first appearance on the earth.

In corroboration of M. Lartet's statement, we must call to mind that the Catholic church, which has raised to the rank of dogma so many unimportant facts, has never desired to treat in this way the idea that man was created only 6000 years ago.

There is, therefore, no need for surprise when we learn that certain members of the Catholic clergy have devoted themselves with energy to the study of pre-historic man. Mgr. Meignan, Bishop of Châlons-sur-Marne, is one of the best-informed men in France as respects this new science; he cultivates it with the utmost zeal, and his personal researches have added much to the sum of our knowledge of this question. Under the title of 'Le Monde et l'Homme Primitif selon la Bible,'[2] the learned Bishop of Châlons-sur-Marne published, in 1869, a voluminous work, in which, taking up the subjects discussed by Marcel de Serres in his "Cosmogonie de Moïse, comparée aux Faits Géologiques,"[3] and enlarging upon the facts which science has recently acquired as to the subject of primitive man, he seeks to establish the coincidence of all these data with the records of Revelation.

M. l'Abbé Lambert has recently published a work on 'L'Homme Primitif et la Bible,'[4] in which he proves that the discoveries of modern science concerning the antiquity of man are in no way opposed to the records of Revelation in the Book of Moses.

Lastly, it is a member of the clerical body, M. l'Abbé Bourgeois, who, more a royalist than the king—that is, more advanced in his views than most contemporary geologists—is in favour of tracing back to the tertiary epoch the earliest date of the existence of man. We shall have to impugn this somewhat exaggerated opinion, which, indeed, we only quote here for the sake of proving that the theological scruples which so long arrested the progress of inquiry with regard to primitive man, have now disappeared, in consequence of the perfect independence of this question in relation to catholic dogma being evidently shown.

Thanks to the mutual support which has been afforded by the three sister-sciences—geology, palæontology, and archæology,—thanks to the happy combinations which these sciences have presented to the efforts of men animated with an ardent zeal for the investigation of the truth;—and thanks, lastly, to the unbounded interest which attaches to this subject, the result has been that the limits which had been so long attributed to the existence of the human species have been extraordinarily extended, and the date of the first appearance of man has been carried back to the night of the darkest ages. The mind, it may well be said, recoils dismayed when it undertakes the computation of the thousands of years which have elapsed since the creation of man.

But, it will naturally be asked, on what grounds do you base this assertion? What evidence do you bring forward, and what are the elements of your proof?

In the following paragraphs we give some of the principal means of examination and study which have directed the efforts of savants in this class of investigation, and have enabled them to create a science of the antiquity of the human species.

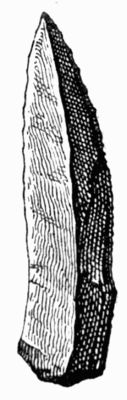

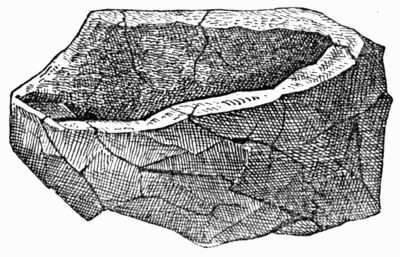

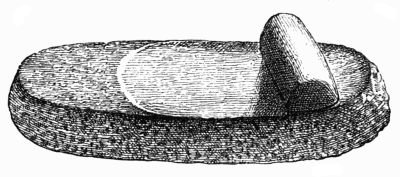

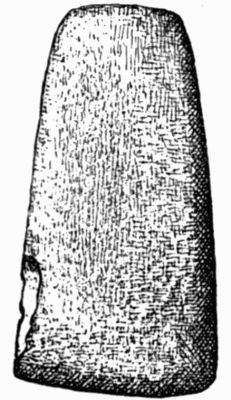

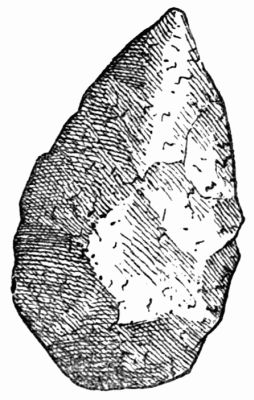

If man existed at any very remote epoch, he must have left traces of his presence in the spots which he inhabited and on the soil which he trod under his feet. However savage his state may be assumed to have been, primitive man must have possessed some implements of fishing and hunting—some weapons wherewith to strike down any prey which was stronger or more agile than himself. All human beings have been in possession of some scrap of clothing; and they have had at their command certain implements more or less rough in their character, be they only a shell in which to draw water or a tool for cleaving wood and constructing some place of shelter, a knife to cut their food, and a lump of stone to break the bones of the animals which served for their nutriment. Never has man existed who was not in possession of some kind of defensive weapon. These implements and these weapons have been patiently sought for, and they have also been found. They have been found in certain strata of the earth, the age of which is known by geologists; some of these strata precede and others are subsequent to the cataclysm of the European deluge of the quaternary epoch.

The fact has thus been proved that a race of men lived upon the earth at the epoch settled by the geological age of these strata—that is, during the quaternary epoch.

When this class of evidence of man's presence—that is, the vestiges of his primitive industry—fails us, a state of things, however, which comparatively seldom occurs, his existence is sometimes revealed by the presence of human bones buried in the earth and preserved through long ages by means of the deposits of calcareous salts which have petrified or rather fossilised them. Sometimes, in fact, the remains of human bones have been found in quaternary rocks, which are, consequently, considerably anterior to those of the present geological epoch.

This means of proof is, however, more difficult to bring forward than the preceding class of evidence; because human bones are very liable to decay when they are buried at shallow depths, and require for any length of preservation a concurrence of circumstances which is but rarely met with; because also the tribes of primitive man often burnt their dead bodies; and, lastly, because the human race then formed but a very scanty population.

Another excellent proof, which demonstrates the existence of man at a geological epoch anterior to the present era, is to be deduced from the intermixture of human bones with those of antediluvian animals. It is evident that if we meet with the bones of the mammoth, the cave-bear, the cave-tiger, &c.,—animals which lived only in the quaternary epoch and are now extinct—in conjunction with the bones of man or the relics of his industry, such as weapons, implements, utensils, &c., we can assert with some degree of certainty that our species was contemporaneous with the above-named animals. Now this intermixture has often been met with under the ground in caves, or deeply buried in the earth.

These form the various kinds of proof which have been made use of to establish the fact of man's presence upon the earth during the quaternary epoch. We will now give a brief recital of the principal investigations which have contributed to the knowledge on which is based the newly-formed science which treats of the practical starting-point of mankind.

Palæontology, as a science, does not count more than half a century of existence. We scarcely seem, indeed, to have raised more than one corner of the veil which covers the relics of an extinct world; as yet, for instance, we know absolutely nothing of all that sleeps buried in the depths of the earth lying under the basin of the sea. It need not, therefore, afford any great ground for surprise that so long a time elapsed before human bones or the vestiges of the primitive industry of man were discovered in the quaternary rocks. This negative result, however, always constituted the chief objection against the very early origin of our species.

The errors and deceptions which were at first encountered tended perhaps to cool down the zeal of the earlier naturalists, and thus retarded the solution of the problem. It is a well-known story about the fossil salamander of the Œningen quarries, which, on the testimony of Scheuchzer, was styled in 1726, the "human witness of the deluge" (homo diluvii testis). In 1787, Peter Camper recognised the fact that this pretended pre-Adamite was nothing but a reptile; this discomfiture, which was a source of amusement to the whole of scientific Europe, was a real injury to the cause of antediluvian man. By the sovereign ascendancy of ridicule, his existence was henceforth relegated to the domain of fable.

The first step in advance was, however, taken in 1774. Some human bones, mingled with remains of the great bear and other species then unknown, were discovered by J. F. Esper, in the celebrated cavern of Gailenreuth, in Bavaria.

Even before this date, in the early part of the eighteenth century, Kemp, an Englishman, had found in London, by the side of elephants' teeth, a stone hatchet, similar to those which have been subsequently found in great numbers in various parts of the world. This hatchet was roughly sketched, and the design published in 1715. The original still exists in the collection at the British Museum.

In 1797, John Frere, an English archæologist, discovered at Hoxne, in Suffolk, under strata of quaternary rocks, some flint weapons, intermingled with bones of animals belonging to extinct species. Esper concluded that these weapons and the men who made them were anterior to the formation of the beds in which they were found.

According to M. Lartet, the honour of having been the first to proclaim the high antiquity of the human species must be attributed to Aimé Boué, a French geologist residing in Germany. In 1823, he found in the quaternary loam (loess) of the Valley of the Rhine some human bones which he presented to Cuvier and Brongniart as those of men who lived in the quaternary epoch.

In 1823, Dr. Buckland, the English geologist, published his 'Reliquiæ Diluvianæ,' a work which was principally devoted to a description of the Kirkdale Cave, in which the author combined all the facts then known which tended in favour of the co-existence of man and the antediluvian animals.

Cuvier, too, was not so indisposed as he is generally said to have been, to admit the existence of man in the quaternary epoch. In his work on 'Ossements Fossiles,' and his 'Discours sur les Révolutions du Globe,' the immortal naturalist discusses the pros and cons with regard to this question, and, notwithstanding the insufficiency of the data which were then forthcoming, he felt warranted in saying:—

"I am not inclined to conclude that man had no existence at all before the epoch of the great revolutions of the earth.... He might have inhabited certain districts of no great extent, whence, after these terrible events, he repeopled the world; perhaps, also, the spots where he abode were swallowed up, and his bones lie buried under the beds of the present seas."

The confident appeals which have been made to Cuvier's authority against the high antiquity of man are, therefore, not justified by the facts.

A second and more decisive step in advance was taken by the discovery of shaped flints and other implements belonging to primitive man, existing in diluvial beds.

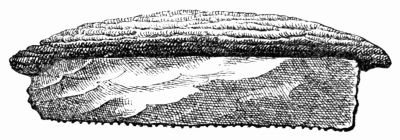

In 1826, M. Tournal, of Narbonne, a French archæologist and geologist, published an account of the discoveries which he had made in a cave in the department of Aude, in which he found bones of the bison and reindeer fashioned by the hand of man, accompanied by the remains of edible shell-fish, which must have been brought there by men who had made their residence in this cave.

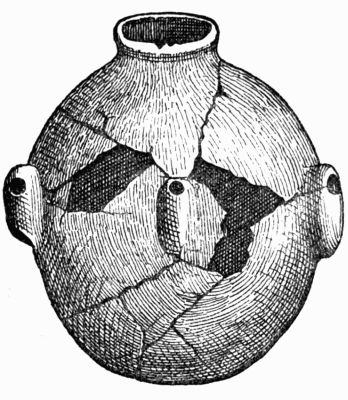

Three years afterwards, M. de Christol, of Montpellier, subsequently Professor in the University of Science of Grenoble, found human bones intimately mixed up with remains of the great bear, hyæna, rhinoceros, &c., in the caverns of Pondres and Souvignargues (Hérault). In the last of these caverns fragments of pottery formed a part of the relics.

All these striking facts were put together and discussed by Marcel de Serres, Professor in the University of Science at Montpellier, in his 'Essai sur les Cavernes.'

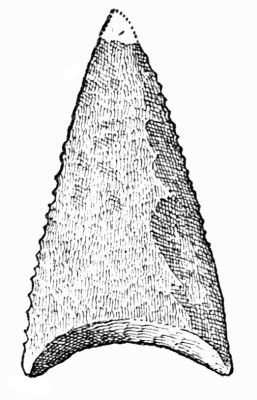

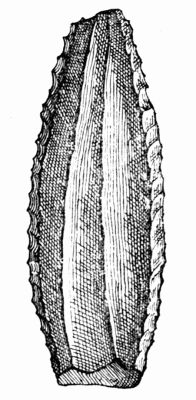

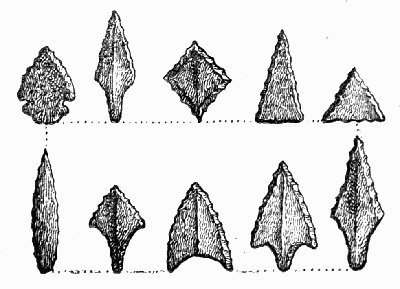

The two bone-caverns of Engis and Enghihoul (Belgium) have furnished proofs of the same kind. In 1833, Schmerling, a learned Belgian geologist, discovered in these caverns two human skulls, mixed with the teeth of the rhinoceros, elephant, bear, hyæna, &c. The human bones were rubbed and worn away like those of the animals. The bones of the latter presented, besides, traces of human workmanship. Lastly, as if no evidence should be wanting, flints chipped to form knives and arrow-heads were found in the same spot.

In connection with his laborious investigations, Schmerling published a work which is now much esteemed, and proves that the Belgian geologist well merited the title of being the founder of the science of the antiquity of man. In this work Schmerling describes and represents a vast quantity of objects which had been discovered in the caverns of Belgium, and introduced to notice the human skull which has since become so famous under the name of the Engis skull. But at that time scientific men of all countries were opposed to this class of ideas, and thus the discoveries of the Belgian geologist attracted no more attention than those of his French brethren who had brought forward facts of a similar nature.

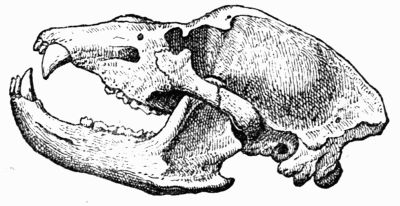

In 1835, M. Joly, at that time Professor at the Lyceum of Montpellier—where I (the author) attended on his course of Natural History—now Professor in the Faculty of Sciences at Toulouse, found in the cave of Nabrigas (Lozère) the skull of a cave-bear, on which an arrow had left its evident traces. Close by was a fragment of pottery bearing the imprints of the fingers of the man who moulded it.

We may well be surprised that, in the face of all these previous discoveries, Boucher de Perthes, the ardent apostle in proclaiming the high antiquity of our species, should have met with so much opposition and incredulity; or that he should have had to strive against so much indifference, when, beginning with the year 1836, he began to maintain this idea in a series of communications addressed to the Société d'Emulation of Abbeville.

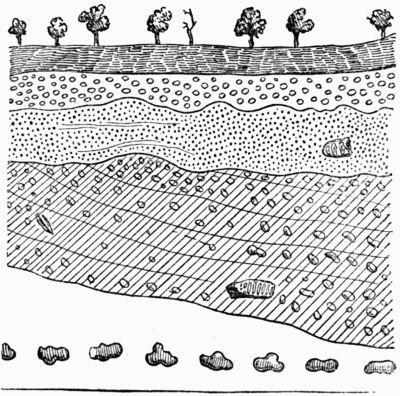

The horizontal strata of the quarternary beds, known under the name of diluvial, form banks of different shades and material, which place before our eyes in indelible characters the ancient history of our globe. The organic remains which are found in them are those of beings who were witnesses to the diluvial cataclysm, and perhaps preceded it by many ages.

"Therefore," says the prophet of Abbeville, "it is in these ruins of the old world, and in the deposits which have become his sole archives, that we must seek out the traditions of primitive man; and in default of coins and inscriptions we must rely on the rough stones which, in all their imperfection, prove the existence of man no less surely than all the glory of a Louvre."

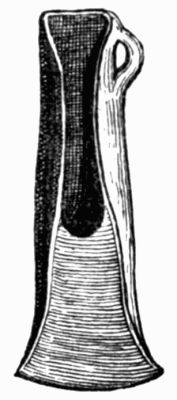

Strong in this conviction, M. Boucher de Perthes devoted himself ardently to the search in the diluvial beds, either for the bony relics of man, or, at all events, for the material indications of his primitive industry. In the year 1838 he had the honour of submitting to the Société d'Emulation, at Abbeville, his first specimens of the antediluvian hatchet.

In the course of the year 1839, Boucher de Perthes took these hatchets to Paris and showed them to several members of the Institute. MM. Alexandre Brongniart, Flourens, Elie de Beaumont, Cordier, and Jomard, gave at first some encouragement to researches which promised to be so fruitful in results; but this favourable feeling was not destined to last long.

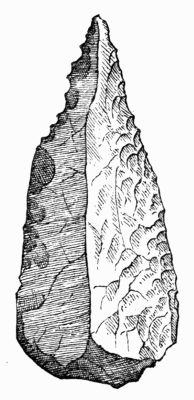

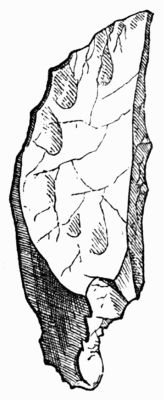

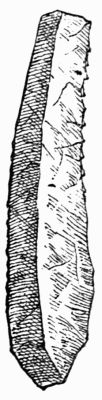

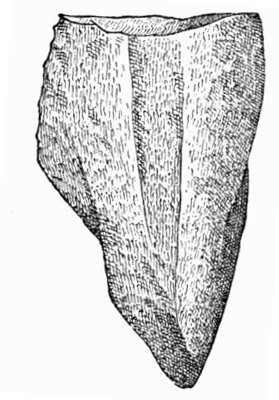

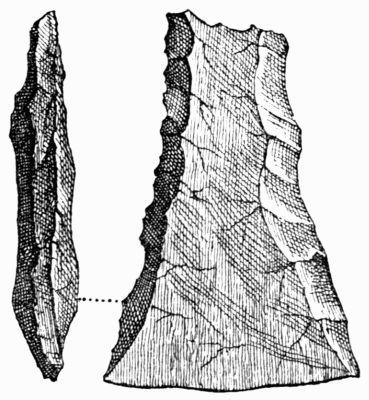

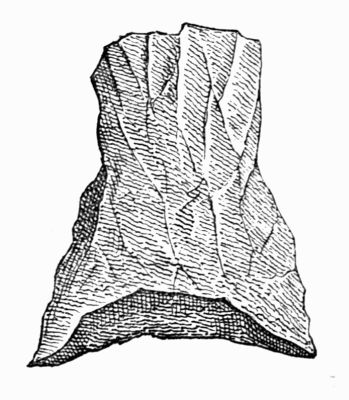

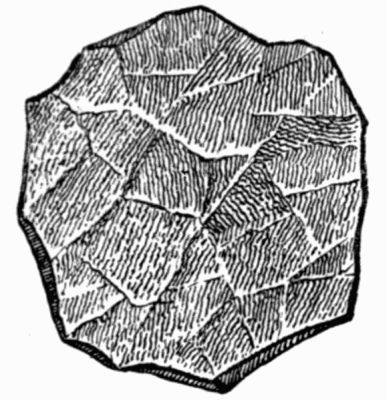

These rough specimens of wrought flint, in which Boucher de Perthes already recognised a kind of hatchet, presented very indistinct traces of chipping, and the angles were blunted; their flattened shape, too, differed from that of the polished hatchets, the only kind that were then known. It was certainly necessary to see with the eyes of faith in order to discern the traces of man's work. "I," says the Abbeville archæologist, "had these 'eyes of faith,' but no one shared them with me." He then made up his mind to seek for help in his labour, and trained workmen to dig in the diluvial beds. Before long he was able to collect, in the quarternary beds at Abbeville, twenty specimens of flint evidently wrought by the hand of man.

In 1842, the Geological Society of London received a communication from Mr. Godwin Austen, who had found in Kent's Hole various wrought objects, accompanied by animal remains, which must have remained there since the deluge.

In 1844, appeared Lund's observations on the caverns of Brazil.

Lund explored as many as 800 caves. In one of them, situated not far from the lake of Semidouro, he found the bones of no less than thirty individuals of the human species, showing a similar state of decomposition to that of the bones of animals which were along with them. Among these animals were an ape, various carnivora, rodents, pachyderms, sloths, &c. From these facts, Lund inferred that man must have been contemporaneous with the megatherium, the mylodon, &c., animals which characterised the quarternary epoch.

Nevertheless, M. Desnoyers, librarian of the Museum of Natural History at Paris, in a very learned article on 'Grottos and Caverns,' published in 1845 in the 'Dictionnaire Universel d'Histoire Naturelle,' still energetically expressed himself in opposition to the hypothesis of the high antiquity of man. But the discoveries continued to go on; and, at the present time, M. Desnoyers himself figures among the partisans of the antediluvian man. He has even gone beyond their opinions, as he forms one among those who would carry back to the tertiary epoch the earliest date of the appearance of our species.

In 1847, M'Enery found in Kent's Hole, a cavern in England, under a layer of stalagmite, the remains of men and antediluvian animals mingled together.

The year 1847 was also marked by the appearance of the first volume of the 'Antiquités Celtiques et Antédiluviennes,' by Boucher de Perthes; this contained about 1600 plates of the objects which had been discovered in the excavations which the author had caused to be made since the year 1836.

The strata at Abbeville, where Boucher de Perthes carried out his researches, belong to the quaternary epoch.

Dr. Rigollot, who had been for ten years one of the most decided opponents of the opinions of Boucher de Perthes, actually himself discovered in 1854 some wrought flints in the quaternary deposits at Saint Acheul, near Amiens, and it was not long before he took his stand under the banner of the Abbeville archæologist.

The fauna of the Amiens deposits is similar to that of the Abbeville beds. The lower deposits of gravel, in which the wrought flints are met with, have been formed by fresh water, and have not undergone either alteration or disturbance. The flints wrought by the hand of man which have been found in them, have in all probability lain there since the epoch of the formation of these deposits—an epoch a little later than the diluvial period. The number of wrought flints which have been taken out of the Abbeville beds is really immense. At Menchecourt, in twenty years, about 100 well-characterised hatchets have been collected; at Saint Gilles twenty very rough, and as many well-made ones; at Moulin-Quignon 150 to 200 well-formed hatchets.

Similar relics of primitive industry have been found also in other localities. In 1853, M. Noulet discovered some in the Infernat Valley (Haute-Garonne); in 1858, the English geologists, Messrs. Prestwich, Falconer, Pengelly, &c., also found some in the lower strata of the Baumann cavern in the Hartz.

To the English geologists whose names we have just mentioned must be attributed the merit of having been the first to bring before the scientific world the due value of the labours of Boucher de Perthes, who had as yet been unsuccessful in obtaining any acceptation of his ideas in France. Dr. Falconer, Vice-president of the Geological Society in London, visited the department of the Somme, in order to study the beds and the objects found in them. After him, Messrs. Prestwich and Evans came three times to Abbeville in the year 1859. They all brought back to England a full conviction of the antiquity and intact state of the beds explored, and also of the existence of man before the deluge of the quaternary epoch.

In another journey, made in company with Messrs. Flower, Mylne, and Godwin Austen, Messrs. Prestwich, Falconer, and Evans were present at the digging out of human bones and flint hatchets from the quarries of St. Acheul. Lastly, Sir C. Lyell visited the spot, and the English geologist, who, up to that time, had opposed the idea of the existence of antediluvian man, was able to say, Veni, vidi, victus fui! At the meeting of the British Association, at Aberdeen, September the 15th, 1855, Sir C. Lyell declared himself to be in favour of the existence of quaternary man; and this declaration, made by the President of the Geological Society of London, added considerable weight to the new ideas.

M. Hébert, Professor of Geology at the Sorbonne, next took his stand under the same banner.

M. Albert Gaudry, another French geologist, made a statement to the Academy of Sciences, that he, too, had found flint hatchets, together with the teeth of horses and fossil oxen, in the beds of the Parisian diluvium.

During the same year, M. Gosse, the younger, explored the sand-pits of Grenelle and the avenue of La Mothe-Piquet in Paris, and obtained from them various flint implements, mingled with the bones of the mammoth, fossil ox, &c.

Facts of a similar character were established at Précy-sur-Oise, and in the diluvial deposits at Givry.

The Marquis de Vibraye, also, found in the cave of Arcy, various human bones, especially a piece of a jaw-bone, mixed with the bones of animals of extinct species.

In 1859, M. A. Fontan found in the cave of Massat (department of Ariége), not only utensils testifying to the former presence of man, but also human teeth mixed up with the remains of the great bear (Ursus spelæus), the fossil hyæna (Hyæna spelæa), and the cave-lion (Felis spelæa).

In 1861, M. A. Milne Edwards found in the cave of Lourdes (Tarn), certain relics of human industry by the side of the bones of fossil animals.

The valleys of the Oise and the Seine have also added their contingent to the supply of antediluvian remains. In the sand-pits in the environs of Paris, at Grenelle, Levallois-Perret, and Neuilly, several naturalists, including MM. Gosse, Martin, and Reboux, found numerous flint implements, associated, in certain cases, with the bones of the elephant and hippopotamus. In the valley of the Oise, at Précy, near Creil, MM. Peigné Delacour and Robert likewise collected a few hatchets.

Lastly, a considerable number of French departments, especially those of the north and centre, have been successfully explored. We may mention the departments of Pas-de-Calais, Aisne, Loire-et-Cher, Indre-et-Loire, Vienne, Allier, Yonne, Saône-et-Loire, Hérault, Tarn-et-Garonne, &c.

In England, too, discoveries were made of an equally valuable character. The movement which was commenced in France by Boucher de Perthes, spread in England with remarkable rapidity. In many directions excavations were made which produced excellent results.

In the gravel beds which lie near Bedford, Mr. Wyatt met with flints resembling the principal types of those of Amiens and Abbeville; they were found in company with the remains of the mammoth, rhinoceros, hippopotamus, ox, horse, and deer. Similar discoveries were made in Suffolk, Kent, Hertfordshire, Hampshire, Wiltshire, &c.

Some time after his return from Abbeville, Mr. Evans, going round the museum of the Society of Antiquaries in London, found in their rooms some specimens exactly similar to those in the collection of Boucher de Perthes. On making inquiries as to their origin, he found that they had been obtained from the gravel at Hoxne by Mr. Frere, who had collected them there, together with the bones of extinct animals, all of which he had presented to the museum, after having given a description of them in the 'Archæologia' of 1800, with this remark: ... "Fabricated and used by a people who had not the use of metals.... The situation in which these weapons were found may tempt us to refer them to a very remote period indeed, even beyond that of the present world."

Thus, even at the commencement of the present century, they were in possession, in England, of proofs of the co-existence of man with the great extinct pachyderms; but, owing to neglect of the subject, scarcely any attention had been paid to them.

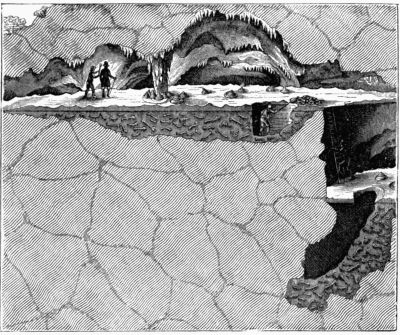

We now come to the most remarkable and most characteristic discoveries of this class which have ever been made. We allude to the explorations made by M. Édouard Lartet, during the year 1860, in the curious pre-historic human burial-place at Aurignac (Haute-Garonne).

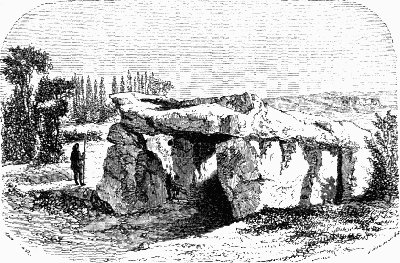

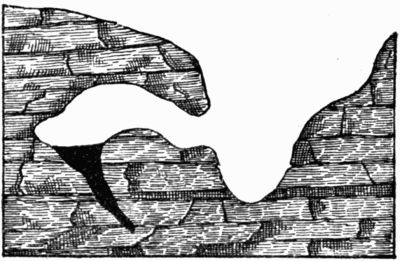

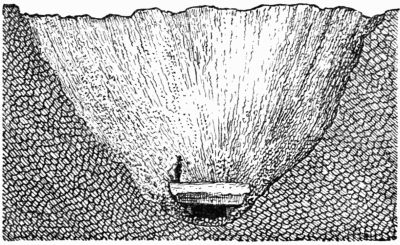

Going down the hill on the road leading from Aurignac, after proceeding about a mile, we come to the point where, on the other side of the dale, the ridge of the hill called Fajoles rises, not more than 65 feet above a rivulet. We then may notice, on the northern slope of this eminence, an escarpment of the rock, by the side of which there is a kind of niche about six feet deep, the arched opening of it facing towards the north-west. This little cave is situated forty-two feet above the rivulet. Below, the calcareous soil slopes down towards the stream.

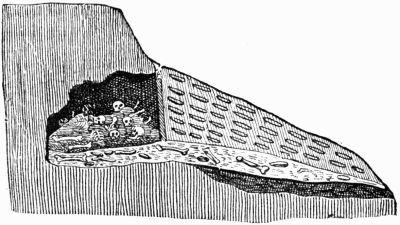

The discovery of this hollow, which is now cleared out, was made entirely by chance. It was hidden by a mass of débris of rock and vegetable-earth which had crumbled down; it had, in fact, only been known as a rabbits' hole. In 1842, an excavating labourer, named Bonnemaison, took it into his head one day to thrust his arm into this hole, and out of it he drew forth a large bone. Being rather curious to search into the mystery, he made an excavation in the slope below the hole, and, after some hours' labour, came upon a slab of sandstone which closed up an arched opening. Behind the slab of stone, he discovered a hollow in which a quantity of human bones were stored up.

It was not long before the news of this discovery was spread far and wide. Crowds of curious visitors flocked to the spot, and many endeavoured to explain the origin of these human remains, the immense antiquity of which was attested by their excessive fragility. The old inhabitants of the locality took it into their heads to recall to recollection a band of coiners and robbers who, half a century before, had infested the country. This decidedly popular inquest and decision was judged perfectly satisfactory, and everyone agreed in declaring that the cavern which had just been brought to light was nothing but the retreat of these malefactors, who concealed all the traces of their crimes by hiding the bodies of their victims in this cave, which was known to these criminals only.

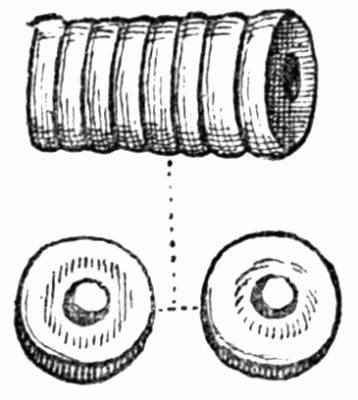

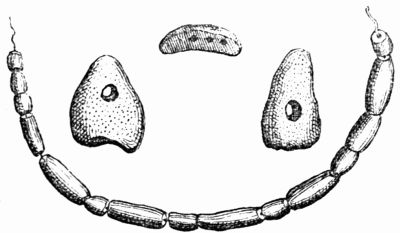

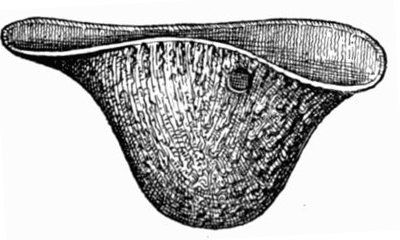

Doctor Amiel, Mayor of Aurignac, caused all these bones to be collected together, and they were buried in the parish cemetery. Nevertheless, before the re-inhumation was proceeded with, he recorded the fact that the skeletons were those of seventeen individuals of both sexes. In addition to these skeletons, there were also found in the cave a number of little discs, or flat rings, formed of the shell of a species of cockle (cardium). Flat rings altogether similar to these are not at all unfrequent in the necklaces and other ornanments of Assyrian antiquity found in Nineveh.

Eighteen years after this event, that is in 1860, M. Édouard Lartet paid a visit to Aurignac. All the details of the above-named discovery were related to him. After the long interval which had elapsed, no one, not even the grave-digger himself, could recollect the precise spot where these human remains had been buried in the village cemetery. These precious relics were therefore lost to science.

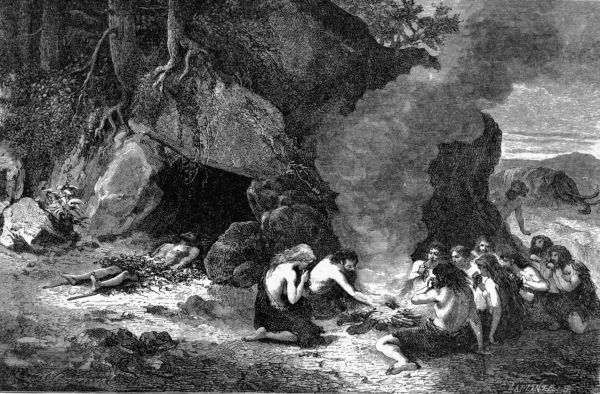

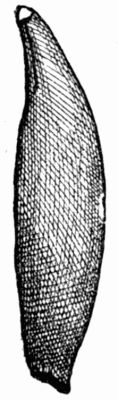

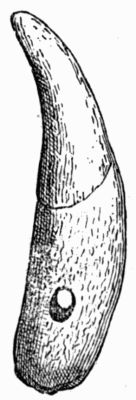

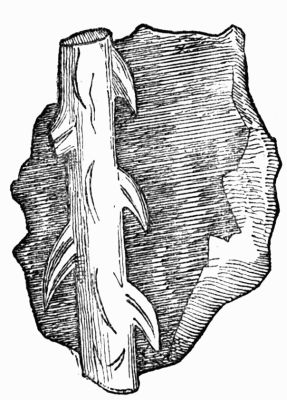

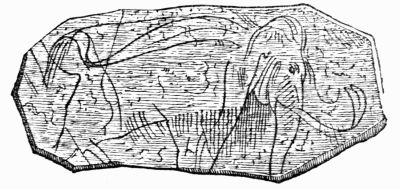

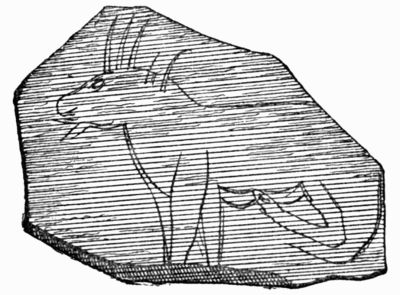

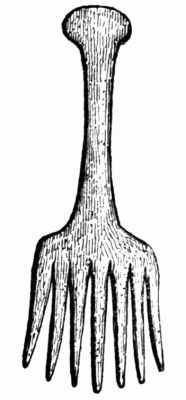

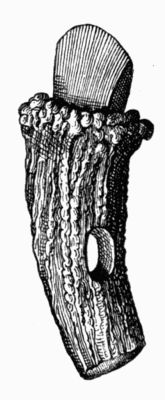

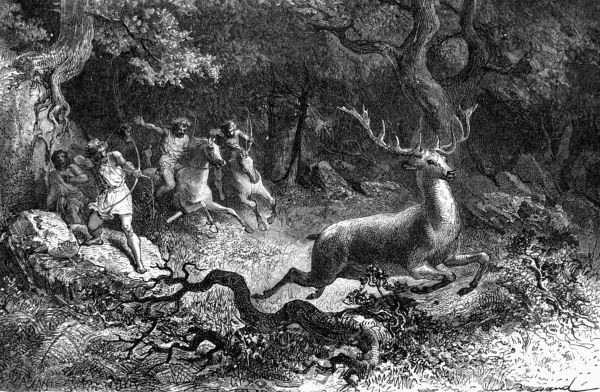

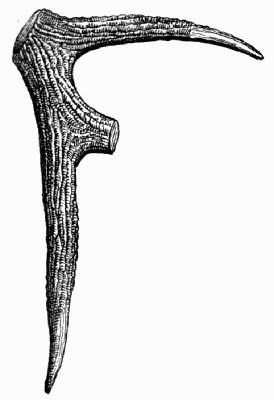

M. Lartet resolved, however, to set on foot some excavations in the cave from which they had been taken, and he soon found himself in possession of unhoped-for treasures. The floor of the cavern itself had remained intact, and was covered with a layer of "made ground" mixed with fragments of stone. Outside this same cave M. Lartet discovered a bed of ashes and charcoal, which, however, did not extend to the interior. This bed was covered with "made ground" of an ossiferous and vegetable character. Inside the cave, the ground contained bones of the bear, the fox, the reindeer, the bison, the horse, &c., all intermingled with numerous relics of human industry, such as implements made of stag or reindeer's-horn, carefully pointed at one end and bevelled off at the other—a pierced handle of reindeer's-horn—flint knives and weapons of different kinds; lastly, a canine-tooth of a bear, roughly carved in the shape of a bird's head and pierced with a hole, &c.

The excavations, having been carried to a lower level, brought to light the remains of the bear, the wild-cat, the cave-hyæna, the wolf, the mammoth, the horse, the stag, the reindeer, the ox, the rhinoceros, &c., &c. It was, in fact, a complete Noah's ark. These bones were all broken lengthwise, and some of them were carbonised. Striæ and notches were found on them, which could only have been made by cutting instruments.

M. Lartet, after long and patient investigations, came to the conclusion that the cave of Aurignac was a human burial-place, contemporary with the mammoth, the Rhinocerus tichorhinus, and other great mammals of the quarternary epoch.

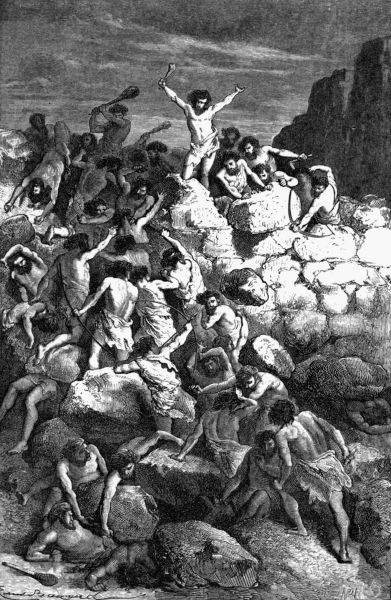

The mode in which the long bones were broken shows that they had been cracked with a view of extracting the marrow; and the notches on them prove that the flesh had been cut off them with sharp instruments. The ashes point to the existence of a fire, in which some of these bones had been burnt. Men must have resorted to this cavern in order to fulfil certain funereal rites. The weapons and animals' bones must have been deposited there in virtue of some funereal dedication, of which numerous instances are found in Druidical or Celtic monuments and in Gallic tombs.

Such are the valuable discoveries, and such the new facts which were the result of the investigations made by M. Édouard Lartet in the cave of Aurignac. In point of fact, they left no doubt whatever as to the co-existence of man with the great antediluvian animals.

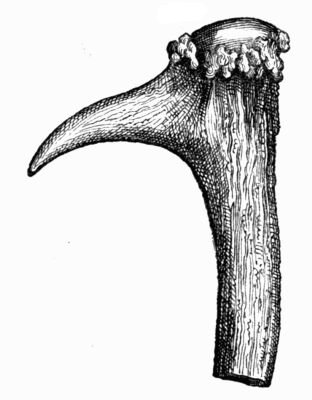

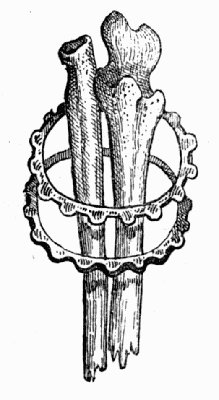

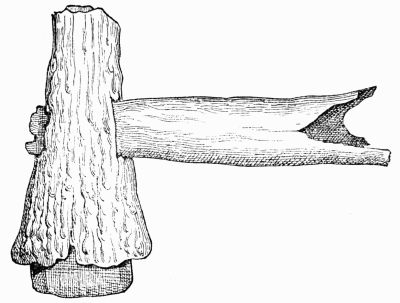

In 1862, Doctor Felix Garrigou, of Tarrascon, a distinguished geologist, published the results of the researches which he, in conjunction with MM. Rames and Filhol, had made in the caverns of Ariége. These explorers found the lower jaw-bones of the great bear, which, with their sharp and projecting canine-tooth, had been employed by man as an offensive weapon, almost in the same way as Samson used the jaw-bone of an ass in fighting with the Philistines.

"It was principally," says M. Garrigou, "in the caves of Lombrives, Lherm, Bouicheta, and Maz-d'Azil that we found the jaw-bones of the great bear and the cave-lion, which were acknowledged to have been wrought by the hand of man, not only by us, but also by the numerous French and English savants who examined them and asked for some of them to place in their collections. The number of these jaw-bones now reaches to more than a hundred. Furnished, as they are, with an immense canine-tooth, and carved so as to give greater facility for grasping them, they must have formed, when in a fresh state, formidable weapons in the hands of primitive man....

"These animals belong to species which are now extinct, and if their bones while still in a fresh state (since they were gnawed by hyænas) were used as weapons, man must have been contemporary with them."

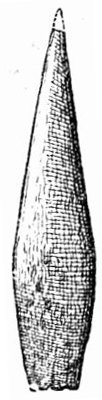

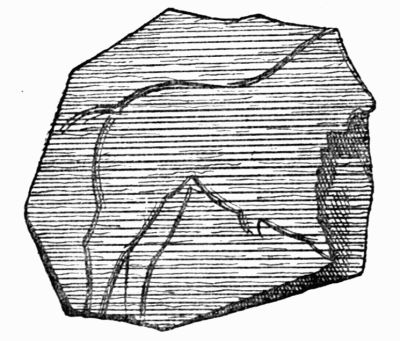

In the cave of Bruniquel (Tarn-et-Garonne), which was visited in 1862 by MM. Garrigou and Filhol, and other savants, there were found, under a very hard osseous breccia, an ancient fire-hearth with ashes and charcoal, the broken and calcined bones of ruminants of various extinct species, flint flakes used as knives, facetted nuclei, and both triangular and quadrangular arrow-heads of great distinctness, utensils in stags' horn and bone—in short, everything which could prove the former presence of primitive man.

About three-quarters of a mile below the cave there was subsequently found, at a depth of about twenty feet, an osseous breccia similar to the first, and likewise containing broken bones and a series of ancient fire-hearths filled with ashes and objects of antediluvian industry. Bones, teeth, and flints were to be collected in bushels.

At the commencement of 1863, M. Garrigou presented to the Geological Society of France the objects which had been found in the caves of Lherm and Bouicheta, and the Abbé Bourgeois published some remarks on the wrought flints from the diluvium of Pont-levoy.

This, therefore, was the position of the question in respect to fossil man, when in 1863, the scientific world were made acquainted with the fact of the discovery of a human jaw-bone in the diluvial beds of Moulin-Quignon, near Abbeville. We will relate the circumstances attending this memorable discovery.

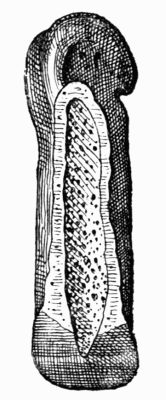

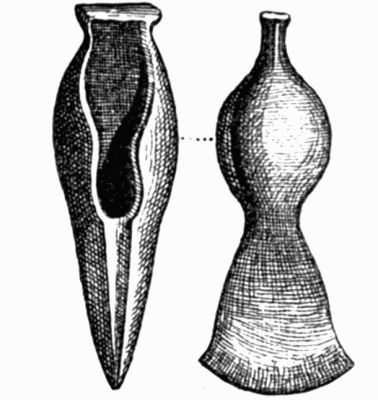

On the 23rd of March, 1863, an excavator who was working in the sand-quarries at Moulin-Quignon brought to Boucher de Perthes at Abbeville, a flint hatchet and a small fragment of bone which he had just picked up. Having cleaned off the earthy coat which covered it, Boucher de Perthes recognised this bone to be a human molar. He immediately visited the spot, and assured himself that the locality where these objects had been found was an argilo-ferruginous vein, impregnated with some colouring matter which appeared to contain organic remains. This layer formed a portion of a virgin bed, as it is called by geologists, that is, without any infiltration or secondary introduction.

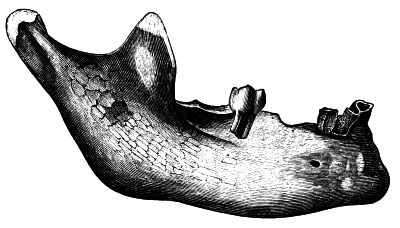

On the 28th of March another excavator brought to Boucher de Perthes a second human tooth, remarking at the same time, "that something resembling a bone was just then to be seen in the sand." Boucher de Perthes immediately repaired to the spot, and in the presence of MM. Dimpré the elder and younger, and several members of the Abbeville Société d'Emulation, he personally extracted from the soil the half of a human lower jaw-bone, covered with an earthy crust. A few inches from this, a flint hatchet was discovered, covered with the same black patina as the jaw-bone. The level where it was found was about fifteen feet below the surface of the ground.

After this event was duly announced, a considerable number of geologists flocked to Abbeville, about the middle of the month of April. The Abbé Bourgeois, MM. Brady-Buteux, Carpenter, Falconer, &c., came one after the other, to verify the locality from which the human jaw-bone had been extracted. All were fully convinced of the intact state of the bed and the high antiquity of the bone which had been found.

Boucher de Perthes also discovered in the same bed of gravel two mammoth's teeth, and a certain number of wrought hatchets. Finally, he found among the bones which had been taken from the Menchecourt quarries in the early part of April, a fragment of another jaw-bone and six separate teeth, which were recognised by Dr. Falconer to be also human.

The jaw-bone found at Moulin-Quignon is very well preserved. It is rather small in size, and appears to have belonged to an aged individual of small stature. It does not possess that ferocious aspect which is noticed in the jaw-bones of certain of the existing human races. The obliquity of the molar-tooth may be explained by supposing some accident, for the molar which stood next had fallen out during the lifetime of the individual, leaving a gap which favoured the obliquity of the tooth which remained in the jaw. This peculiarity is found also in several of the human heads in the collection of the Museum of Natural History in Paris.

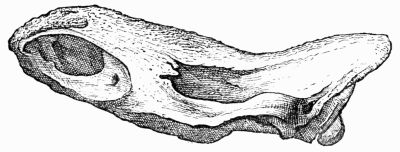

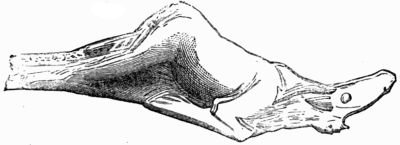

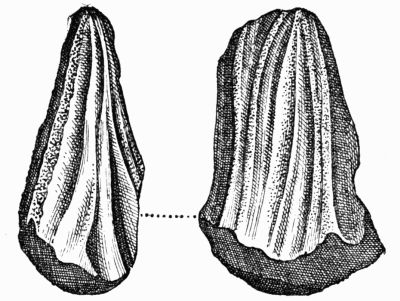

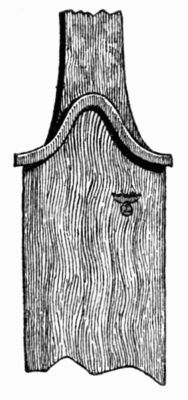

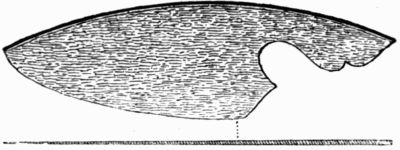

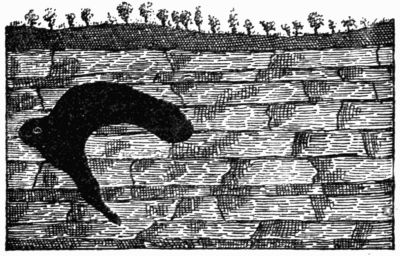

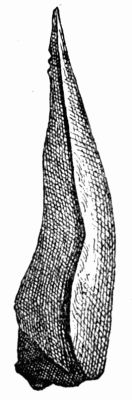

The jaw-bone of the man of Moulin-Quignon, which is represented here (fig. 1) in its natural size, and drawn from the object itself, which is preserved in the Anthropological Gallery of the Museum of Natural History of Paris, does not show any decided points of difference when compared with those of individuals of existing races.

The same conclusion was arrived at as the result of the comparative examination which was made of the jaw-bones found by MM. Lartet and De Vibraye in the caves of Aurignac and Arcy; the latter remains were studied by M. Quatrefages in conjunction with Pruner-Bey, formerly physician to the Viceroy of Egypt, and one of the most distinguished French anthropologists.

On the 20th of April, 1863, M. de Quatrefages announced to the institute the discovery which had been made by Boucher de Perthes, and he presented to the above-named learned body the interesting object itself, which had been sent from Abbeville.

When the news of this discovery arrived in England it produced no slight sensation.

Some of the English savants who had more specially devoted their attention to the study of this question, such as Messrs. Christy, Falconer, Carpenter, and Busk, went over to France, and in conjunction with Boucher de Perthes and several members of the Académie des Sciences of Paris, examined the exact locality in which the hatchets and the human jaw-bone had been found; they unanimously agreed in recognising the correctness of the conclusions arrived at by the indefatigable geologist of Abbeville.[5]

This discovery of the hatchets and the human jaw-bone in the quaternary beds of Moulin-Quignon completed the demonstration of an idea already supported by an important mass of evidence. Setting aside its own special value, this discovery, added to so many others, could not fail to carry conviction into most minds. From this time forth the doctrine of the high antiquity of the human race became an acknowledged idea in the scientific world.

Before closing our historical sketch, we shall have to ask, what was the precise geological epoch to which we shall have to carry back the date of man's first appearance on this our earth.

The beds which are anterior to the present period, the series of which forms the solid crust of our globe, have been divided, as is well known, into five groups, corresponding to the same number of periods of the physical development of the earth. These are in their order of age: the primitive rocks, the transition rocks, the secondary rocks, the tertiary and quaternary rocks. Each of these epochs must have embraced an immense lapse of time, since it has radically exhausted the generation both of animals and plants which was peculiar to it. Some idea may be formed of the extreme slowness with which organic creatures modify their character, when we take into consideration that our contemporary fauna, that is to say, the collection of animals of every country which belong to the geological period in which we exist, has undergone little, if any, alteration during the thousands of years that it has been in being.

Is it possible for us to date the appearance of the human race in those prodigiously-remote epochs which correspond with the primitive, the transition, or the secondary rocks? Evidently no! Is it possible, indeed, to fix this date in the epoch of the tertiary rocks? Some geologists have fancied that they could find traces of the presence of man in these tertiary rocks (the miocene and pliocene). But this is an opinion in which we, at least, cannot make up our minds to agree.

In 1863, M. Desnoyers found in the upper strata of the tertiary beds (pliocene) at Saint-Prest, in the department of Eure, certain bones belonging to various extinct animal species; among others those of an elephant (Elephas meridionalis), an animal which did not form a part of the quaternary fauna. On most of these bones he ascertained the existence of cuts, or notches, which, in his opinion, must have been produced by flint implements. These indications, according to M. Desnoyers, are signs of the existence of man in the tertiary epoch.

This opinion, however, Sir Charles Lyell hesitates to accept. Moreover, we could hardly depend upon an accident so insignificant as that of a few cuts or notches made upon a bone, in order to establish a fact so important as that of the high antiquity of man. We must also state that it is a matter of question whether the beds which contained these notched bones really belong to the tertiary group.

The beds which correspond to the quaternary epoch are, therefore, those in which we find unexceptionable evidence of the existence of man. Consequently, in the quaternary epoch which preceded the existing geological period, we must place the date of the first appearance of mankind upon the earth.

If the purpose is entertained of discussing, with any degree of certainty, the history of the earliest days of the human race—a subject which as yet is a difficult one—it is requisite that the long interval should be divided into a certain number of periods. The science of primitive man is one so recently entered upon, that those authors who have written upon the point can hardly be said to have properly discussed and agreed upon a rational scheme of classification. We shall, in this work, adopt the classification proposed by M. Édouard Lartet, which, too, has been adopted in that portion of the museum of Saint-Germain which is devoted to pre-historic antiquities. Following this course, we shall divide the history of primitive mankind into two great periods:

1st. The Stone Age;

2nd. The Metal Age.

These two principal periods must also be subdivided in the following mode. The "Stone Age" will embrace three epochs:

1st. The epoch of extinct animals (or of the great cave-bear and the mammoth).

2nd. The epoch of migrated existing animals (or the reindeer epoch).

3rd. The epoch of domesticated existing animals (or the polished-stone epoch).

The "Metal Age" may also be divided into two periods:

1st. The Bronze Epoch;

2nd. The Iron Epoch.

The following synoptical table will perhaps bring more clearly before the eyes of our readers this mode of classification, which has, at least, the merit of enabling us to make a clear and simple statement of the very incongruous facts which make up the history of primitive man:

| The Stone Age. | 1st. Epoch of extinct animals (or of the great bear and mammoth). | |

| 2nd. Epoch of migrated existing animals (or the reindeer epoch). | ||

| 3rd. Epoch of domesticated existing animals (or the polished-stone epoch). | ||

| The Metal Age. | 1st. The Bronze Epoch. | |

| 2nd. The Iron Epoch. |

FOOTNOTES:

[1] 'Nouvelles Recherches sur la Coexistence de l'Homme et des grands Mammifères Fossiles réputés charactéristiques de la dernière période Géologique,' by Éd. Lartet, 'Annales des Sciences Naturelles,' 4th ser. vol. xv. p. 256.

[2] 1 vol. 8vo., Paris, 1869; V. Palme.

[3] 2 vols. 12mo., 3rd edit., Paris, 1859; Lagny frères.

[4] Pamphlet, 8vo., Paris, 1869; Savy.

[5] It should rather have been said, that the ultimate and well-considered judgment of the English geologists was against the authenticity of the Moulin-Quignon jaw.—See Dr. Falconer's 'Palæontological Memoirs,' vol. ii. p. 610; and Sir C. Lyell's 'Antiquity of Man,' 3rd ed. p. 515. (Note to Eng. Trans.)

THE STONE AGE.

I.

The Epoch of Extinct Species of Animals; or, of the Great Bear and Mammoth.

CHAPTER I.

Man must have lived during the time in which the last representatives of the ancient animal creation—the mammoth, the great bear, the cave-hyæna, the Rhinoceros tichorinus, &c.—were still in existence. It is this earliest period of man's history which we are now about to enter upon.

We have no knowledge of a precise nature with regard to man at the period of his first appearance on the globe. How did he appear upon the earth, and in what spot can we mark out the earliest traces of him? Did he first come into being in that part of the world which we now call Europe, or is it the fact that he made his way to this quarter of our hemisphere, having first seen the light on the great plateaux of Central Asia?

This latter opinion is the one generally accepted. In the work which will follow the present volume we shall see, when speaking of the various races of man, that the majority of naturalists admit nowadays one common centre of creation for all mankind. Man, no doubt, first came into being on the great plateaux of Central Asia, and thence was distributed over all the various habitable portions of our globe. The action of climate and the influences of the locality which he inhabited have, therefore, determined the formation of the different races—white, black, yellow, and red—which now exist with all their infinite subdivisions.

But there is another question which arises, to which it is necessary to give an immediate answer, for it has been and is incessantly agitated with a degree of vehemence which may be explained by the nature of the discussion being of so profoundly personal a character as regards all of us: Was man created by God complete in all parts, and is the human type independent of the type of the animals which existed before him? Or, on the contrary, are we compelled to admit that man, by insensible transformations, and gradual improvements and developments, is derived from some other animal species, and particularly that of the ape?

This latter opinion was maintained at the commencement of the present century by the French naturalist, de Lamarck, who laid down his views very plainly in his work entitled 'Philosophie Zoologique.' The same theory has again been taken up in our own time, and has been developed, with no small supply of facts on which it might appear to be based, by a number of scientific men, among whom we may mention Professor Carl Vogt in Switzerland, and Professor Huxley in England.

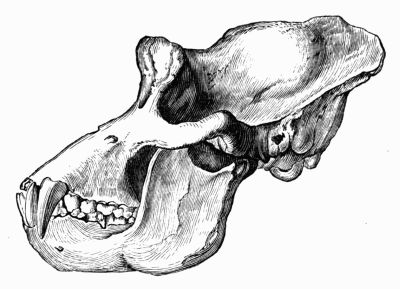

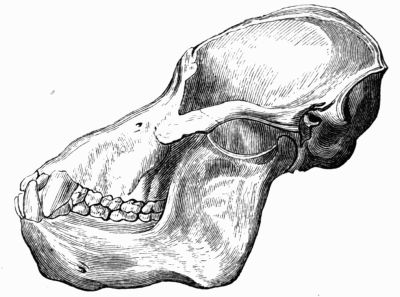

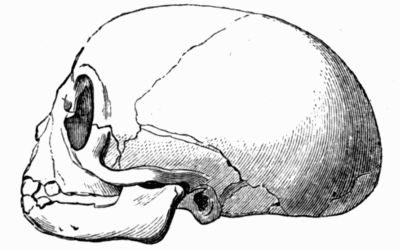

We strongly repudiate any doctrine of this kind. In endeavouring to establish the fact that man is nothing more than a developed and improved ape, an orang-outang or a gorilla, somewhat elevated in dignity, the arguments are confined to an appeal to anatomical considerations. The skull of the ape is compared with that of primitive man, and certain characteristics of analogy, more or less real, being found to exist between the two bony cases, the conclusion has been arrived at that there has been a gradual blending between the type of the ape and that of man.

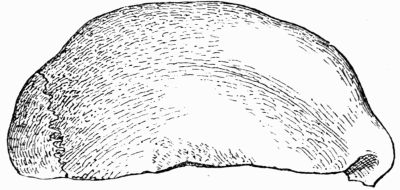

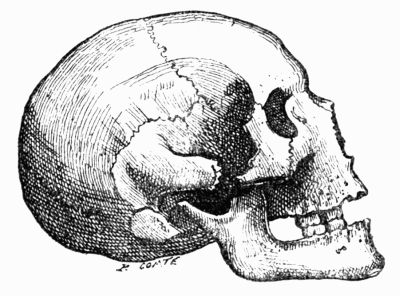

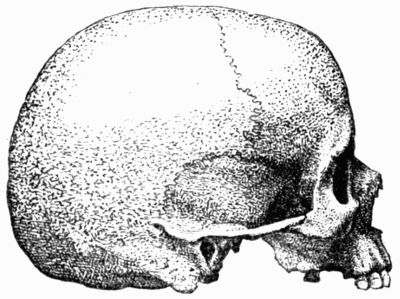

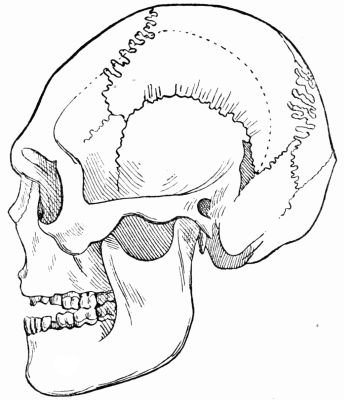

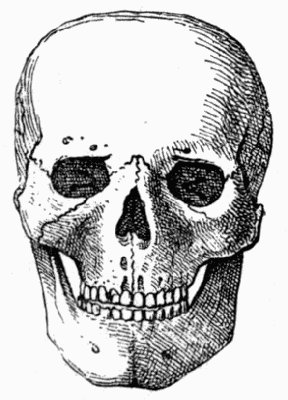

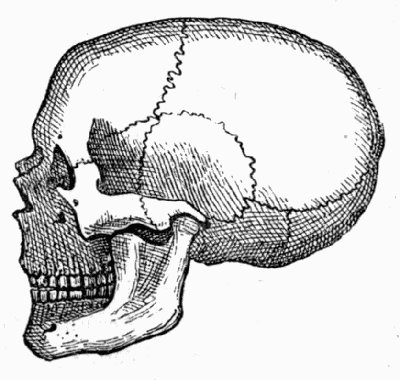

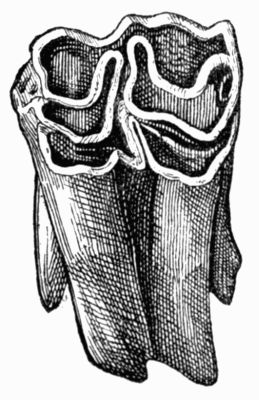

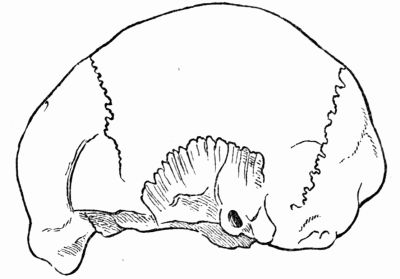

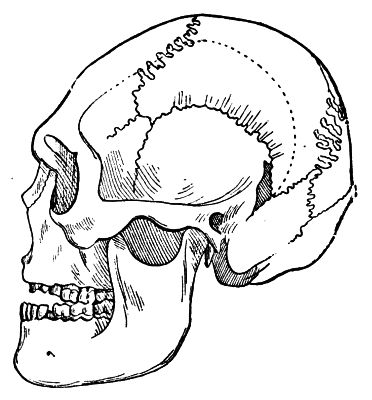

We may observe, in the first place, that these analogies have been very much exaggerated, and that they fail to stand their ground in the face of a thorough examination of the facts. Only look at the skulls which have been found in the tombs belonging to the stone age, the so-called Borreby skull for instance—examine the human jaw-bone from Moulin-Quignon, the Meilen skull, &c., and you will be surprised to see that they differ very little in appearance from the skulls of existing man. One would really imagine, from what is said by the partisans of Lamarck's theory, that primitive man possessed the projecting jaw of the ape, or at least that of the negro. We are astonished, therefore, when we ascertain that, on the contrary, the skull of the man of the stone age is almost entirely similar in appearance to those of the existing Caucasian species. Special study is, indeed, required in order to distinguish one from the other.

If we place side by side the skull of a man belonging to the Stone Age, and the skulls of the principal apes of large size, these dissimilarities cannot fail to be obvious. No other elements of comparison, beyond merely looking at them, seem to be requisite to enable us to refute the doctrine of this debased origin of mankind.

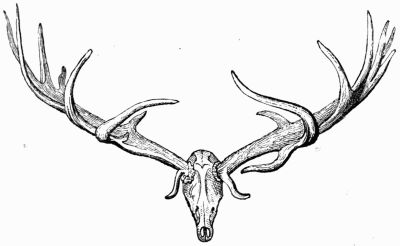

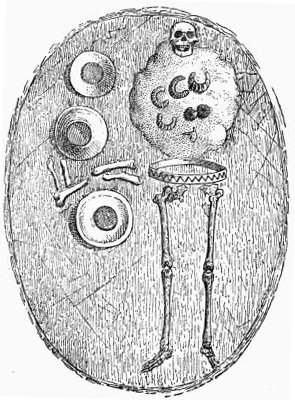

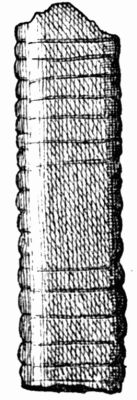

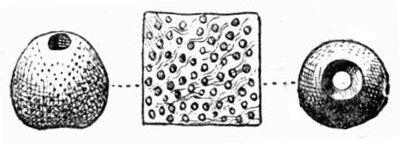

The figure annexed represents the skull of a man belonging to the stone age, found in Denmark; to this skull, which is known by the name of the Borreby skull, we shall have to allude again in the course of the present work; fig. 3 represents the skull of a gorilla; fig. 4 that of an orang-outang; fig. 5 that of the Cynocephalus ape; fig. 6 that of the Macacus. Place the representation of the skull found in Denmark in juxtaposition with these ill-favoured animal masks, and then let the reader draw his own inference, without pre-occupying his mind with the allegations of certain anatomists imbued with contrary ideas.

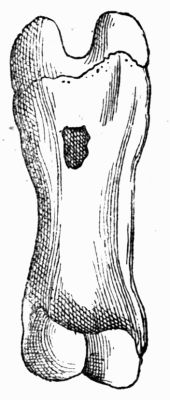

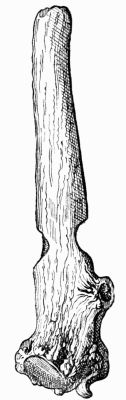

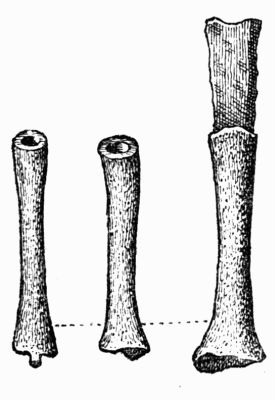

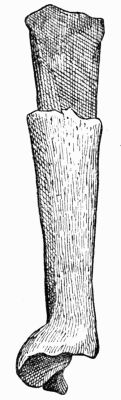

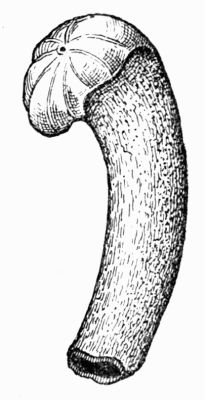

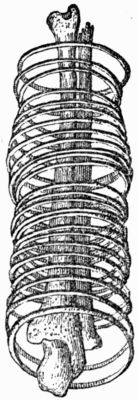

Finding themselves beaten as regards the skulls, the advocates of transmutation next appeal to the bones. With this aim, they exhibit to us certain similarities of arrangement existing between the skeleton of the ape and that of primitive man. Such, for instance, is the longitudinal ridge which exists on the thigh-bone, which is as prominent in primitive man as in the ape. Such, also, is the fibula, which is very stout in primitive man, just as in the ape, but is rather slender in the man of the present period.

When we are fully aware how the form of the skeleton is modified by the kind of life which is led, in men just as in animals, we cannot be astonished at finding that certain organs assume a much higher development in those individuals who put them to frequent and violent use, than in others who leave these same organs in a state of comparative repose.

If it be a fact that the man of the epoch of the great bear and the mammoth had a more robust leg, and a more largely developed thigh-bone than most of the races of existing man, the reason simply is, that his savage life, which was spent in the midst of the wild beasts of the forest, compelled him to make violent exertions, which increased the size of these portions of his body.

Thus it is found that great walkers have a bulky calf, and persons leading a sedentary life have slender legs. These variations in the structure of the skeleton are owing, therefore, to nothing but a difference in the mode of life.

Why is it, however, that the skeleton is the only point taken into consideration when analogies are sought for between man and any species of animal? If equal investigation were given to other organs, we should arrive at a conclusion which would prove how unreasonable comparisons of this kind are. In fact, if man possesses the osseous structure of the ape, he has also the anatomical structure of many other animals, as far as regards several organs. Are not the viscera of the digestive system the same, and are they not organised on the same plan in man as in the carnivorous animals? As the result of this, would you say that man is derived from the tiger, that he is nothing but an improved and developed lion, a cat transmuted into a man? We may, however, just as plausibly draw this inference, unless we content ourselves with devoting our attention to the skeleton alone, which seems, indeed, to be the only part of the individual in which we are to interest ourselves, for what reason we know not.

But, in point of fact, this kind of anatomy is pitiable. Is there nothing in man but bones? Do the skeleton and the viscera make up the entire sum of the human being? What will you say, then, ye blind rhetoricians, about the faculty of intelligence as manifested in the gift of speech? Intelligence and speech, these are really the attributes which constitute man; these are the qualities which make him the most complete being in creation, and the most privileged of God's creatures. Show me an ape who can speak, and then I will agree with you in recognising it as a fact that man is nothing but an improved ape! Show me an ape who can make flint hatchets and arrow-heads, who can light a fire and cook his food, who, in short, can act like an intelligent creature—then, and then only, I am ready to confess that I am nothing more than an orang-outang revised and corrected.

It is not, however, our desire to speak of a question which has been the subject of so much controversy as that of the anatomical resemblance between the ape and the man without thoroughly entering into it; we have, indeed, no wish to shun the discussion of the point. On the present occasion, we shall appeal to the opinion of a savant perfectly qualified in such matters; we allude to M. de Quatrefages, Professor of Anthropology in the Museum of Natural History at Paris.

M. de Quatrefages, in his work entitled 'Rapport sur le Progrès de l'Anthropologie,' published in 1868, has entered rather fully into the question whether man is descended from the ape or not. He has summed up the contents of a multitude of contemporary works on this subject, and has laid down his opinion—the perfect impossibility, in an anatomical point of view, of this strange and repugnant genealogy.

The following extract from his work will be sufficient to make our readers acquainted with the ideas of the learned Professor of Anthropology with regard to the question which we are now considering:

"Man and apes in general," says M. de Quatrefages, "present a most striking contrast—a contrast on which Vicq-d'Azyr, Lawrence, and M. Serres have dwelt in detail for some considerable time past. The former is a walking animal, who walks upon his hind legs; all apes are climbing animals. The whole of the locomotive system in the two groups bears the stamp of these two very different intentions; the two types, in fact, are perfectly distinct.

"The very remarkable works of Duvernoy on the 'Gorilla,' and of MM. Gratiolet and Alix on the 'Chimpanzee,' have fully confirmed this result as regards the anthropomorphous apes—a result very important, from whatever point of view it is looked at, but of still greater value to any one who wishes to apply logically Darwin's idea. These recent investigations prove, in fact, that the ape type, however highly it may be developed, loses nothing of its fundamental character, and remains always perfectly distinct from the type of man; the latter, therefore, cannot have taken its rise from the former.

"Darwin's doctrine, when rationally adapted to the fact of the appearance of man, would lead us to the following results:

"We are acquainted with a large number of terms in the Simian series. We see it branching out into secondary series all leading up to anthropomorphous apes, which are not members of one and the same family, but corresponding superior terms of three distinct families (Gratiolet). In spite of the secondary modifications involved by the developments of the same natural qualities, the orang, the gorilla, and the chimpanzee remain none the less fundamentally mere apes and climbers (Duvernoy, Gratiolet, and Alix). Man, consequently, in whom everything shows that he is a walker, cannot belong to any one of these series; he can only be the higher term of a distinct series, the other representatives of which have disappeared, or, up to the present time, have evaded our search. Man and the anthropomorphous apes are the final terms of two series, which commence to diverge at the very latest as soon as the lowest of the apes appear upon the earth.

"This is really the way in which a true disciple of Darwin must reason, even if he solely took into account the external morphological characteristics and the anatomical characteristics which are the expression of the former in the adult animal.

"Will it be said that when the degree of organisation manifested in the anthropomorphous apes had been once arrived at, the organism underwent a new impulse and became adapted for walking? This would be, in fact, adding a fresh hypothesis, and its promoters would not be in a position to appeal to the organised gradation presented by the quadrumanous order as a whole on which stress is laid as leading to the conclusion against which I am contending: they would be completely outside Darwin's theory, on which these opinions claim to be based.

"Without going beyond these purely morphological considerations, we may place, side by side, for the sake of comparison, as was done by M. Pruner-Bey, the most striking general characteristics in man and in the anthropomorphous apes. As the result, we ascertain this general fact—that there exists 'an inverse order of the final term of development in the sensitive and vegetative apparatus, in the systems of locomotion and reproduction' (Pruner-Bey).

"In addition to this, this inverse order is equally exhibited in the series of phenomena of individual development.

"M. Pruner-Bey has shown that this is the case with a portion of the permanent teeth. M. Welker, in his curious studies of the sphenoïdal angle of Virchow, arrived at a similar result. He demonstrated that the modifications of the base of the skull, that is, of a portion of the skeleton which stands in the most intimate relation to the brain, take place inversely in the man and ape. This angle diminishes from his birth in man, but, on the contrary, in the ape it becomes more and more obtuse, so as sometimes to become entirely extinct.

"But there is also another fact which is of a still more important character: it is that this inverse course of development has been ascertained to exist even in the brain itself. This fact, which was pointed out by Gratiolet, and dwelt upon by him on various occasions, has never been contested either at the Société d'Anthropologie or elsewhere, and possesses an importance and significance which may be readily comprehended.

"In man and the anthropomorphous ape, when in an adult state, there exists in the mode of arrangement of the cerebral folds a certain similarity on which much stress has been laid; but this resemblance has been, to some extent, a source of error, for the result is attained by an inverse course of action. In the ape, the temporo-sphenoïdal convolutions, which form the middle lobe, make their appearance, and are completed, before the anterior convolutions which form the frontal lobe. In man, on the contrary, the frontal convolutions are the first to appear, and those of the middle lobe are subsequently developed.

"It is evident that when two organised beings follow an inverse course in their growth, the more highly developed of the two cannot have descended from the other by means of evolution.

"Embryology next adds its evidence to that of anatomy and morphology, to show how much in error they are who have fancied that Darwin's ideas would afford them the means of maintaining the simial origin of man.

"In the face of all these facts, it may be easily understood that anthropologists, however little in harmony they may sometimes be on other points, are agreed on this, and have equally been led to the conclusion that there is nothing that permits us to look at the brain of the ape as the brain of man smitten with an arrest of development, or, on the other hand, the brain of man as a development of that of the ape (Gratiolet); that the study of animal organism in general, and that of the extremities in particular, reveals, in addition to a general plan, certain differences in shape and arrangement which specify two altogether special and distinct adaptations, and are incompatible with the idea of any filiation (Gratiolet and Alix); that in their course of improvement and development, apes do not tend to become allied to man, and conversely the human type, when in a course of degradation, does not tend to become allied to the ape (Bert); finally, that no possible point of transition can exist between man and the ape, unless under the condition of inverting the laws of development (Pruner-Bey), &c.

"What, we may ask, is brought forward by the partisans of the simial origin of man in opposition to these general facts, which here I must confine myself to merely pointing out, and to the multitude of details of which these are only the abstract?

"I have done my best to seek out the proofs alleged, but I everywhere meet with nothing but the same kind of argument—exaggerations of morphological similarities which no one denies; inferences drawn from a few exceptional facts which are then generalised upon, or from a few coincidences in which the relations of cause and effect are a matter of supposition; lastly, an appeal to possibilities from which conclusions of a more or less affirmative character are drawn.

"We will quote a few instances of this mode of reasoning.

"1st. The bony portion of the hand of man and of that of certain anthropomorphous apes present marked similarities. Would it not therefore have been possible for an almost imperceptible modification to have ultimately led to identity?

"MM. Gratiolet and Alix reply to this in the negative; for the muscular system of the thumb establishes a profound difference, and testifies to an adaptation to very different uses.

"2nd. It is only in man and the anthropomorphous apes that the articulation of the shoulder is so arranged as to allow of rotatory movements. Have we not here an unmistakable resemblance?

"The above-named anatomists again reply in the negative; for even if we only take the bones into account, we at once see that the movements could not be the same; but when we come to the muscular system, we find decisive differences again testifying to certain special adaptations."

"These rejoinders are correct, for when locomotion is the matter in question, it is evident that due consideration must be paid to the muscles, which are the active agents in that function at least as much as the bones, which only serve as points of attachment and are only passive.

"3rd. In some of the races of man, the arch of the skull, instead of presenting a uniform curve in the transverse direction, bends a little towards the top of the two sides, and rises towards the median line (New Caledonians, Australians, &c.). It is asked if this is not a preliminary step towards the bony crests which rise in this region in some of the anthropomorphous apes?

"Again we reply in the negative; for, in the latter, the bony crests arise from the walls of the skull, and do not form any part of the arch.

"4th. Is it not very remarkable that we find the orang to be brachycephalous, just like the Malay, whose country it inhabits, and that the gorilla and chimpanzee are dolichocephalous like the negro? Is not this fact a reason for our regarding the former animal as the ancestor of the Malays, and the latter of the African nations?

"Even if the facts brought forward were correct, the inference which is drawn from them would be far from satisfactory. But the coincidence which is appealed to does not exist. In point of fact, the orang, which is essentially a native of Borneo, lives among the Dyaks and not among the Malays; now the Dyaks are rather dolichocephalous than brachycephalous. With respect to gorillas being dolichocephalous, they cannot at least be so generally; as out of three female specimens of this ape which were examined, two were brachycephalous (Pruner-Bey).

"5th. The brains of microcephalous individuals present a mixture of human and simial characteristics, and point to some intermediate conformation, which was normal at some anterior epoch, but at the present time is only realised by an arrest of development and a fact of atavism.

"Gratiolet's investigations of the brain of the ape, normal man and small-brained individuals, have shown that the similarities pointed out are purely fallacious. People have thought that they could detect them, simply because they have not examined closely enough. In the last named, the human brain is simplified; but this causes no alteration in the initial plan, and this plan is not that which is ascertained to exist in the ape. Thus Gratiolet has expressed an opinion which no one has attempted to controvert: 'The human brain differs the more from that of the ape the less the former is developed, and an arrest of development could only exaggerate this natural difference.... The brains of microcephalous individuals, although often less voluminous and less convoluted than those of the anthropomorphous apes, do not on this account become like the latter.... The idiot, however low he may be reduced, is not a beast; he is nothing but a deteriorated man.'

"The laws of the development of the brain in the two types, laws which I mentioned before, explain and justify this language; and the laws of which it is the summary are a formal refutation of the comparison which some have attempted to make between the contracted human brain, and the animal brain, however developed.

"6th. The excavations which have been made in intact ancient beds have brought to light skulls of ancient races of man, and these skulls present characteristics which approximate them to the skull of the ape. Does not this pithecoïd stamp, which is very striking on the Neanderthal skull in particular, argue a transition from one type to another, and consequently filiation?

"This argument is perhaps the only one which has been brought forward with any degree of precision, and it is often recurred to. Is it, on this account, more demonstrative? Let the reader judge for himself.

"We may, in the first place, remark that Sir C. Lyell does not venture to pronounce affirmatively as to the high antiquity of the human remains discovered by Dr. Fuhlrott, and that he looked upon them, at the most, as contemporary with the Engis skull, in which the Caucasian type of head was reproduced.

"Let us, however, admit that the Neanderthal skull belongs to the remote antiquity to which it has been assigned; what, then, is in reality the significance of this skull? Is it actually a link between the head of the man and that of the ape? And does it not find some analogy in comparatively modern races?

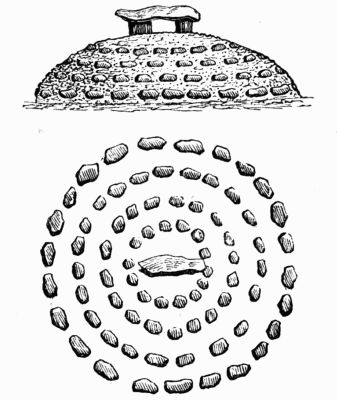

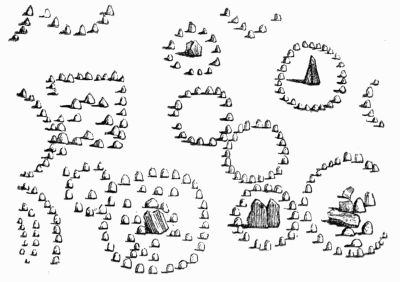

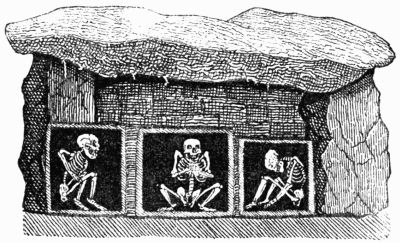

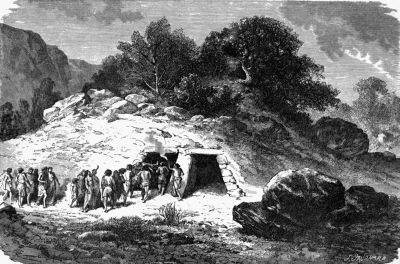

"Many writings have been published on these questions, and, as it appears to me, some light has gradually been thrown upon the subject. There is no doubt that this skull is really remarkable for the enormous size of its superciliary ridges, the length and narrowness of the bony case, the slight elevation of the top of the skull. But these features are found to be much less exceptional than was at first supposed, in default of any means of instituting a just comparison; very far, indeed, from justifying the approximation which some have endeavoured to make, this skull is, in all its characteristics, essentially human. Mr. Busk, in England, has pointed out the great affinity which is established, by the prominence of the superciliary ridges and the depression of the upper region, between certain Danish skulls from Borreby and the Neanderthal skull. Dr. Barnard Davis has described the still greater similarities existing between this very fossil and a skull in his collection. Gratiolet forwarded to the Museum the skull of an idiot of the present time, which was almost identical with it in everything, although in slighter proportions, &c.