.

TEMPLUM It will be well to preface the important part of this article, which relates to temple buildings, by a few remarks about the strict meaning of the word templum, and the distinction originally existing between the words aedes, templum, sacellum, delubrum, and fanum. That this distinction was confused by lax usage, especially in poetry, and that it in time disappeared altogether, must of course be admitted; but that it existed not merely in a very early period of Latin is clear from the fact that Augustus marks it when he calls the Temple of Apollo on the Palatine and that of Mars Ultor templa, and others aedes (Monum. Ancyr. 19: see below).

The word templum is from the same root as the Greek τέμενος, i. e. some space cut off and separated. Its augural signification was beyond a doubt its genuine Roman use. The templum in augury had a twofold meaning: 1. The space of sky which the augur marked off with his lituus by imaginary lines, the cardo from north to south and the decumanus from east to west, thus dividing the space observed into four regions (Serv. ad Aen. 1.92; Varro, L. L. 7.7). From this augural templum caeli comes the familiar “caelestia templa” of Lucretius (1.120, &c.), which, as Munro remarks, “conveys a solemn and stately notion.” 2. The space of earth to be included for observations, which was a rectangular space called locus effatus, or more fully locus effatus conceptis verbis, i.e. a space bounded by points which he announced aloud, naming (conceptis verbis) trees or other stationary objects as the limits for observation in each direction. This space also was divided into four regions by lines (cardo and decumanus, as above), and the observer (usually a magistrate, who qua observer was the auspex as distinguished from the augur) sat at the point (decussis) where these imaginary lines intersected (Varro, L. L. 7.8; Liv. 1.18; Cic. de Div. 1.1. 7, 31). It will be seen that in both these senses of the augural templum the idea of cutting off (τέμνω) is preserved, and also that the shape of the templum was rectangular. Further, in the place where the observer was to sit (except where there was, as at Rome, a permanently established auguraculum: see Vol. I. p. 251 b), the observer pitched a tent [TABERNACULUM], also quadrangular in shape, with a single opening, commanding the spaces of earth and sky which formed the templa. There has been some difference of opinion as to the aspect of this tabernaculum. Regell's opinion seems to be correct, that for observing lightning by the templa in caelo the tabernaculum looked to the south, but for observing birds by the templa in terra it faced the east, whence, as in Liv. 1.18, the south is on the right hand, the north on the left (see Regell in Jahrb. f. Philol. u. Paedagog. 123.607 ff., and Mau's note in Marquardt, Staatsverw. iii.2 403). The tabernaculum was called templum minus, and thus we have a templum of real as well as of imaginary lines: so Festus (5.157), “templum est locus ita effatus” (by [p. 2.773]imaginary lines) aut ita saeptus (by real enclosure) ut [ex] una parte pateat angulosque adfixos habeat ad terram; “and Servius (Serv. ad Aen. 4.200),” templum dicunt non solum quod potest claudi (by imaginary lines) verum etiam quod palis aut hastis aut aliqua tali re (as in a permanent auguraculum) et linteis aut loris (the linen or leathern tent) aut simili re saeptum est quod effatum est (i.e. the imaginary lines are made real: see also Mommsen, Staatsrecht, i.3 105). [For the method of taking auspices, see AUSPICIA; and for the connexion between the shape of the pomerium and the augural templum, see POMERIUM pp. 443, 444.]

This use of templum for augury was, we cannot doubt, the original religious sense of templum, and accordingly, in the extended meanings which the word subsequently takes of consecrated spaces, and later (perhaps not till near the end of the Republic) of buildings, it is still confined to such spaces or buildings as have been “inaugurated” by the augurs, and moreover the shape is still rectangular. Such inaugurated and consecrated places were (1) those for the assembly of the senate, curiae (Hostilia Pompeia, Julia) or actual temples of the gods, since the senate could only transact business “in loco per augurem constituto” (Gel. 14.7); (2) the Comitia Curiata and Centuriata (Liv. 5.52; V. Max. 4.5); (3) the Rostra (Cic. in Vatin. 10.24; Liv. 8.14); (4) a temple in the ordinary sense, i. e. a house built for a god and inaugurated as well as consecrated. For the building of a temple, or indeed for any permanent inaugurated templum, it was necessary first that the ground should not only be effatus (i.e. have pronounced limits), but also be liberatus; that is to say, any prior claims upon the ground not merely of private ownership, but of fana or sacella which might once have been upon it, had to be abrogated [EXAUGURATIO], and the ground and building assigned by the augurs to that deity to whose service it was to be dedicated, and next the temple itself was consecrated by the pontifices (cf. Serv. ad Aen. 1.446; Liv. 1.55).

Templum, however, in this sense of a god's house, was probably a comparatively modern equivalent for aedes or aedes sacra. Jordan (in Hermes, xiv. pp. 567 ff.) presses this somewhat far, giving aedes as the proper term for a Roman or Italian temple, and templum for one in the colonies; and explaining the passage above mentioned from the Mon. Ancyr. on the theory that Augustus called the temples at Rome, which were built on publicum solum, aedes, while those to Apollo and Mars, built on his privatum solum, he called templa. In this same passage, however, he speaks of “duo et octoginta templa deum,” and it seems to us a truer view that the use of templum for aedes was coming in before the end of the Republic, and that Augustus in speaking by name of pre-existing temples uses the term which originally described them, but in those which he has just built uses the term now in vogue. Cicero certainly uses the word templum as “temple” frequently (e.g. de Div. 1.2, 4); and the figurative use in Lucretius (4.264; 5.103) of the mouth as “templum linguae” and the breast as “templum mentis” implies that templum was then the term in common parlance for a building enshrining some deity. It must be noticed that the round shape which we see in the Aedes Vestae and some others did not properly belong to a templum, which should follow the rectangular augural temple; and with this agrees the fact alluded to above, that this round aedes was consecrated by the pontifices, but not inaugurated by the augurs, and hence not a possible meeting-place for the senate (Serv. ad Aen. 7.153; Gel. 14.7). It is a significant fact that the shrine of the Dea Diva in the Arval grove, which like that of Vesta belongs to the most primitive Roman religion, was also a round building, and it might reasonably be inferred that the round shape was the earlier form for a god's house, just as the circular hut built round a central pole is the early architecture for a human habitation, and that the rectangular temple came later in with the augural templum.

The word delubrum is derived from the same root as lavabrum (or labrum), pollubrum, &c., and thus meant originally a place of purification (for we must certainly reject the derivation from delibrare, “to strip the bark and make a wooden image” ): that such a rite of purification belonged to the old unroofed loca sacra, where there might be merely an enclosure with an altar or shrine, there can be no doubt; and from this aspect of purification (which in later temples appears in the ἀπορραντήρια or labra) such a sacred space might be called delubrum, i.e. the dedicated plot of ground within which were rites of purification, and so in the Argean procession “ad aedem dei Fidii in delubro ubi aeditimus habitare solet” the delubrum is clearly the sacred precinct, as distinguished from the aedes, but in time delubrum, like sacellum, was used both for the sacred enclosed spot and the shrine upon it; cf. “regiis temporibus delubra parva facta” (Varro ap. Non. 494), where the delubra are contrasted with the later and more stately aedes or templum. We are here speaking only of strict definition. In poets no distinction between aedes, templum, and delubrum is observed: even Cicero's usage is open to doubt, though it may be remarked that the passages cited by Marquardt as showing a promiscuous use of the words (N. D. 2.43, 83, and various passages in the Verrine orations) are speaking of Sicilian, not of Roman temples. In later prose, though not in Livy, all distinction vanishes (cf. Plin. Nat. 35.144; 36.26).

Though fanum is found in a general sense for any locus sacer consecrated by the pontifices, but not inaugurated [FANUM], and so often means sacred buildings, aedes or sacella, as well as sacred areas such as luci, yet it is also true, as Jordan points out, that the strict use of fanum did not include aedes or actual houses of the gods at Rome, but only “loca sacra cum aris [or later also” cum aediculis “ sine tecto; ” and that when it is used of temples it belongs only to temples of non-Roman deities: this explains the origin of fanaticus, which was first applied to such “fanatic” priests as those of Isis. (See further on this subject Marquardt, Staatsverwaltung, iii.2 151 ff.; and especially Jordan in Hermes, 14.567 ff.) [G.E.M]

TEMPLE ARCHITECTURE.

Greek Temples.--Among the Greeks, as among most Pagan races, the temple was not a building [p. 2.774]in which a congregation met and worshipped, but was rather regarded as the house and treasury of the god.1 In the most primitive times temples (in the later sense of the word) seem to have been very rare, their place being taken by an altar in the open air, or by a sacred stone (βαίτυλος) which was both the symbol of some divine presence and the place of sacrifice. See Prof. Robertson Smith, Religion of the Semites, lect. v. The kingly heroes of Homer, such as Odysseus, themselves played the part of a priest, and offered sacrifice to Zeus Herkeios on the altar in the fore-court of their palaces. Such an open-air altar was discovered by Dr. Dörpfeld in the courtyard of the palace at Tiryns; and this domestic altar survived at the entrance of Greek houses long after actual temples had been built [see DOMUS]. Other primitive forms of temples were natural caves in the rock, or hollow trees, the former being usually associated with the cults of Chthonian deities. The word μέγαρον, which is sometimes applied to temples of Chthonian deities, is supposed to be derived from a Phoenician word meaning a cavern or cleft in the rock.

The next stage appears to have been the construction of a small cell-like building, consisting of a mere cella or σηκὸς without any columns or subdivision into more than one chamber. The most remarkable examples which still exist of this early form of temple are to be seen in the Island of Euboea, especially one near Karystos, on an elevated site on Mount Ocha, overlooking the sea. This is a rectangular stone building, about 40 feet by 24 feet (externally) in plan. In one of the long sides is a small central doorway, formed of three large blocks of stone, between two slit-like windows. The roof consists of large thin slabs, each projecting beyond the course below, till they meet at the ridge. Light and air are given by a hypaethral opening in the stone roof--a long narrow slit, 19 feet long by 18 inches wide. The height of the walls internally is 7 feet. The worship of Hera was the special cult in this part of Euboea.

The words used by the Greeks to denote temples are chiefly these: ναός, or in Attic νεώς, equivalent to the Latin aedes, the “house” of the god; ἱερὸν frequently has a more extended meaning, including not only the ναὸς but also the sacred enclosure around it, τέμενος (Thuc. 4.90) or ἱερὸς περίβολος. In other cases ἱερὸν and ναὸς are used as equivalent terms, as, e. g. by Pausanias (8.45.3), where he records the building of the Temple of Athene Alea at Tegaea: Ἀθηνᾶς τῆς Ἀλέας τὸ ἱερὸν τὸ ἀρχαῖον ἐποιήσεν Ἄλεος: χρόνῳ δὲ ὕστερον κατασκευάσαντο οἱ Τεγεᾶται τῇ Θεῷ ναὸν μέγαν. A peculiar phrase is used by Homer (Hom. Il. 9.404) to denote the Temple of Apollo at Delphi: he calls it the λάϊνος οὐδός, “stone threshold,” as if using a part for the whole building. Other words--such as μέγαρον, ἄδυτον, ἀνάκτορον, σηκός--seem to have been taken from terms originally used for parts of domestic buildings, meaning “the hall,” “the private chambers,” “the royal house,” “the cell or inner chamber.” The words μέγαρον and σηκὸς μυστικὸς were especially applied to the abnormal Hall of the Mysteries at Eleusis, which was also called the τελεστήριον, in reference to the initiations which there tools place. Strictly speaking, it was not a temple at all. The real Temple of Demeter, which stood near the Hall of Initiation, was a very much smaller building.

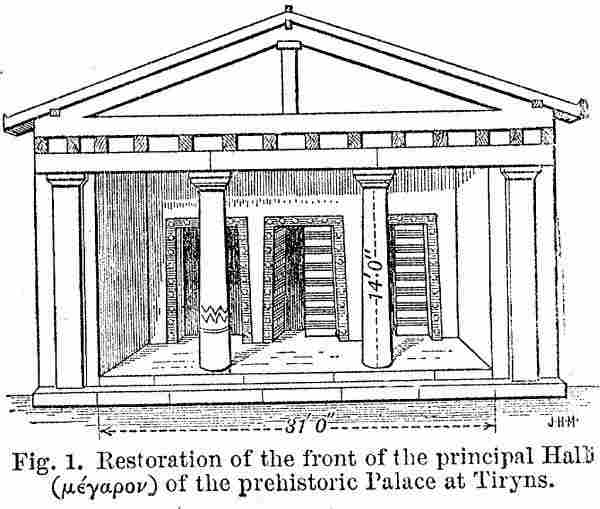

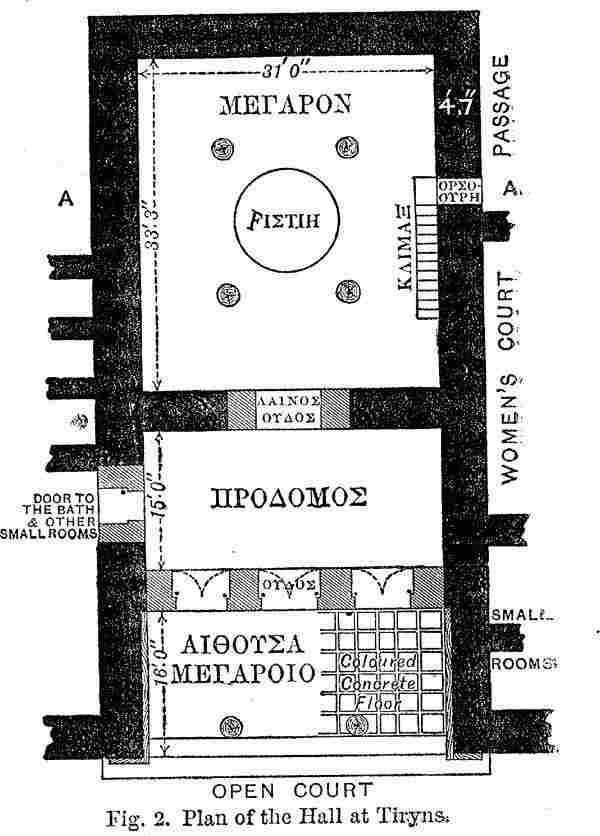

Returning to the development of the Greek temple, the next stage after the simple σηκός, such as that on Mount Ocha, was probably a building with a prostyle portico, constructed mainly of unburnt brick with wooden columns closely resembling the hall or μέγαρον of a pre-Homeric palace, such as that which Dr. Dörpfeld excavated within the Acropolis of Tiryns. The accompanying figures (1 and 2) show the probable

Fig. 1. Restoration of the front of the principal Hall (μέγαρον) of the prehistoric Palace at Tiryns.

Fig. 2. Plan of the Hall at Tiryns.

[p. 2.775]appearance of this hall when perfect. Both in plan and in its façade it is clearly the prototype of the later stone temples of the Greeks. The walls were of unburnt brick, covered with hard fine stucco decorated with painting; the lowest courses of the wall were of stone, to a height of about two feet above the ground, in order to prevent injury to the unbaked clay of the bricks from rising damp. A sort of survival of this structural stone plinth existed even in the latest temples of the Greeks, which were wholly built of marble: the lowest course immediately above the pavement is usually very much deeper than the rest of the masonry, as if marking a change of material even when none exists. The columns both of the portico and of the inner chamber were of wood, each resting on a carefully levelled block of stone.

This use of crude brick for the walls and wood for the columns appears to have survived in many cases till very late, more especially in the private houses of the Greeks. Dr. Dörpfeld has pointed out that even the Heraion at Olympia was originally built in this primitive fashion, but that stone columns were introduced one by one as the wood pillars decayed. Thus we see columns of many different dates among the existing remains. Pausanias (5.16) mentions one ancient wooden column as still existing in situ in the Heraion at the time of his visit. Of the walls nothing remains but the stone plinth, carefully levelled to receive the first course of crude bricks, so the original wall probably was never rebuilt in stone. The entablature was apparently of wood, like the columns, as no remains of stone cornice or architrave were found.

Vitruvius (2.3) describes the careful manner in which crude bricks (lateres) were made by mixing gravel, pounded pottery, and chopped straw with clay which had been long exposed to the weather. He records that a decree of the city of Utica ordained that none of these bricks should be used till they had been inspected by a magistrate to see if they were thoroughly dried, and had been kept the required time, which was five years, after they had been moulded. [LATER]

In 1888 an interesting discovery was made by Dr. Halbherr at Gortyn in Crete. Excavations on the site of the Pythion, or Temple of the Pythian Apollo, revealed some remains of an early temple built of large blocks of stone without any cement. The building, which from the inscriptions cut on the outside of its walls is apparently a work of the 7th or 6th century B.C., consisted simply of one rectangular chamber, a mere cella, without columns or pronaos; though in later times a pronaos was added in front of the entrance. A very interesting point about this primitive temple was the fact that it had been lined internally with plates of bronze, like the great “beehive tomb” at Mycenae, and other Greek structures of prehistoric date. The bronze pins which fixed these plates still remain on the internal face of the great blocks of which the walls were built. (See Halbherr in Monumenti antichi, Part I., 1889; published by the Acad. dei Lincei.)

The last stage of the development of the Greek temple was a building with walls and columns wholly of stone or marble, such as those of which many examples still remain.

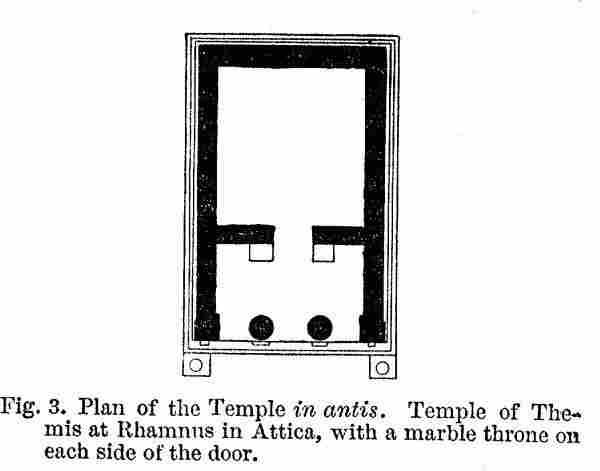

Vitruvius (3.2) classifies temples according to the arrangement of their columns in the following manner:--I. Ναὸς ἐν παραστάσι, in antis, with two columns between the antae of the projecting side walls (see fig. 3). [ANTAE]

Fig. 3. Plan of the Temple in antis. Temple of Themis at Rhamnus in Attica, with a marble throne on each side of the door.

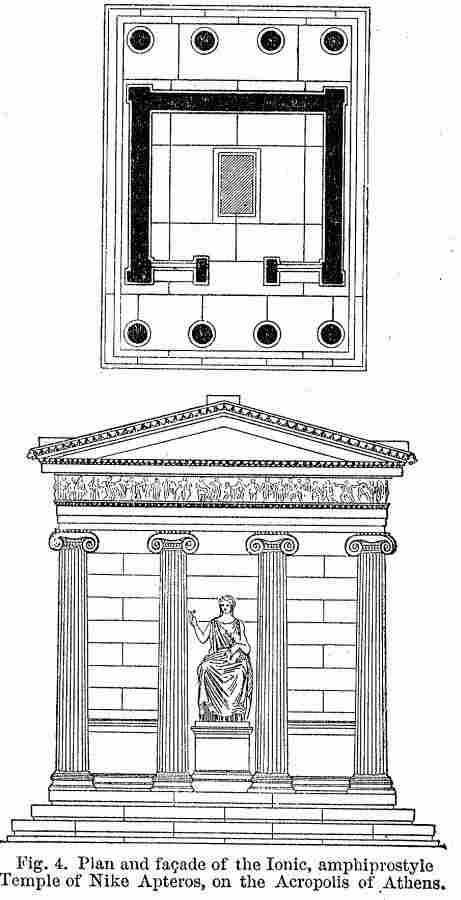

II. Πρόστυλος, prostylos, with four columns in front. III. Ἀμφιπρόστυλος, amphaiprostylos, with four columns at each end (see figure 4).

ZZZ

Fig. 4. Plan and façade of the Ionic, amphiprostyle Temple of Nike Apteros, on the Acropolis of Athens.

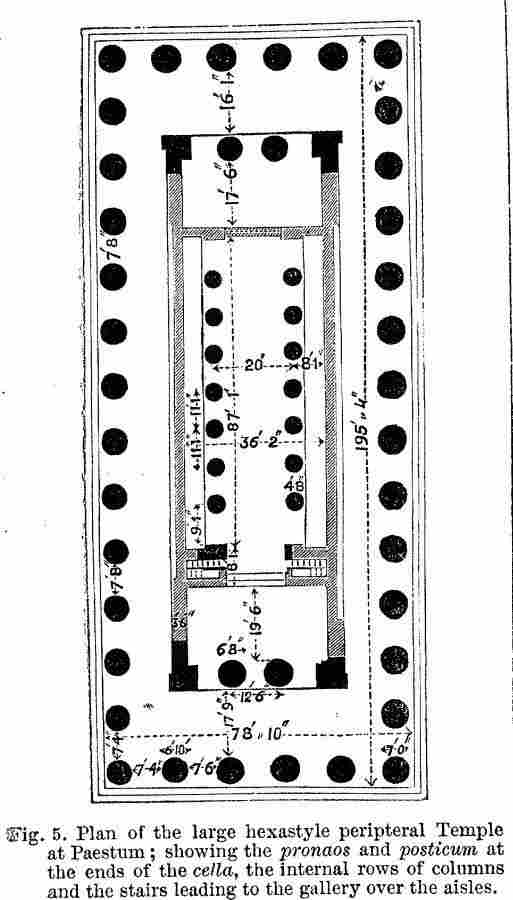

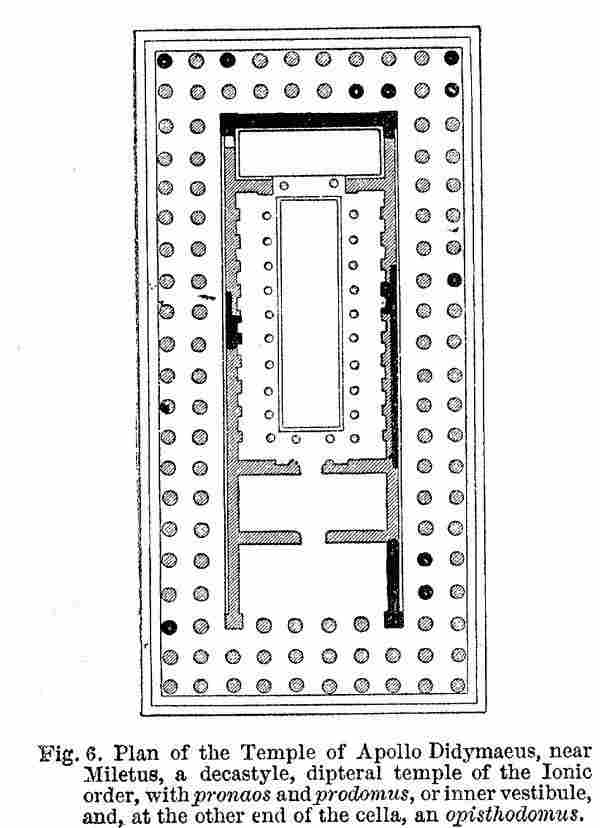

IV. Περίπτερος, peripteros, with columns along both sides and ends (see figure 5). V. Δίπτερος, dipteros, with a double range of columns all round (see figure 6). VI. Ψευδοδίπτερος, [p. 2.776]pseudo-dipteros, with one range of columns only, but placed at the same distance from the cella wall as the outer range of

Fig. 5. Plan of the large hexastyle peripteral Temple at Paestum; showing the pronaos and posticum at the ends of the cella, the internal rows of columns and the stairs leading to the gallery over the aisles.

Fig. 6. Plan of the Temple of Apollo Didymaeus, near Miletus, a decastyle, dipteral temple of the Ionic order, with pronaos and prodomus, or inner vestibule, and, at the other end of the cella, an opisthodomus.

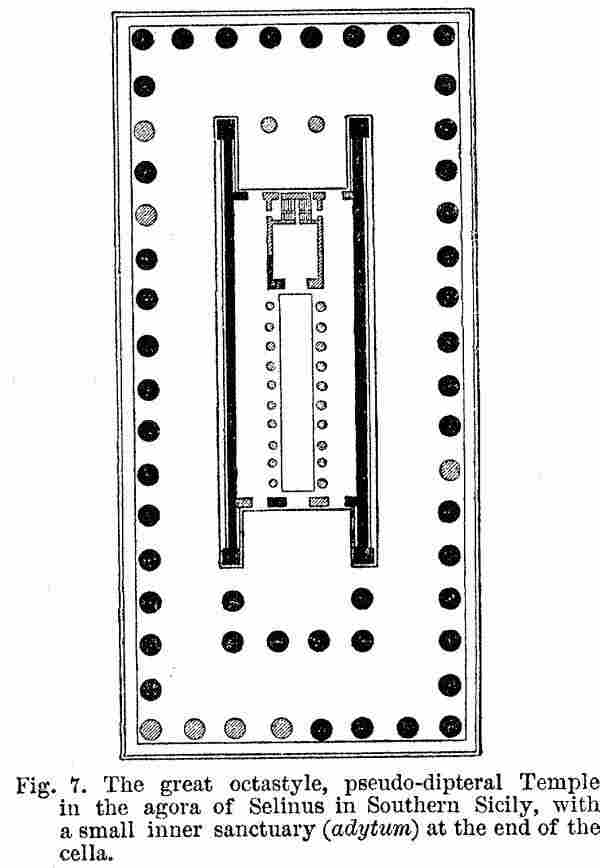

the dipteral temple (see fig. 7). VII. Ψευδοπερίπτερος, pseudo-peripteral, is another variety which Vitruvius does not give in his list (3.2),

Fig. 7. The great octastyle, pseudo-dipteral Temple in the agora of Selinus in Southern Sicily, with a small inner sanctuary (adytum) at the end of the cella.

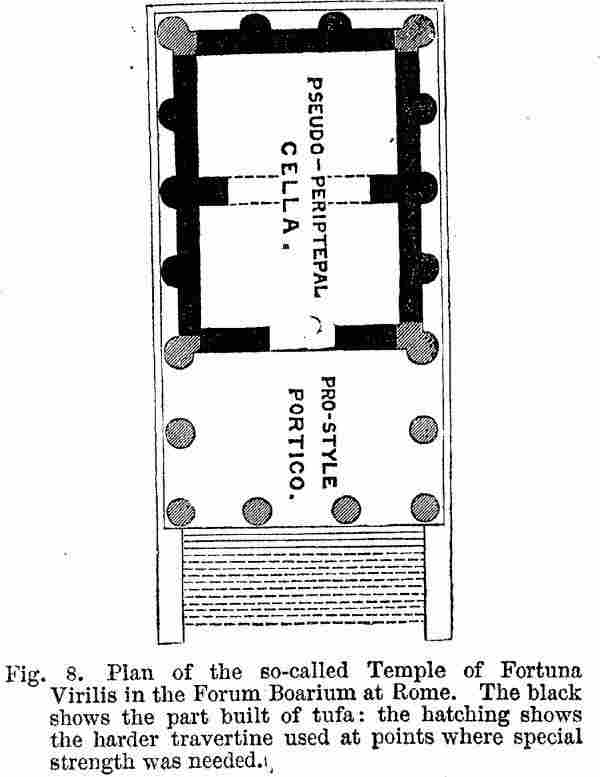

though he mentions it later on (4.8.6). This has no complete columns along the sides, but half or “engaged” columns built into the side walls of the cella. The great Temple of Zeus at Agrigentum is an example of this, dating c. 500 B.C. or earlier. This plan was more commonly used by the Greeks for tombs, such as the lion tomb at Cnidus, than for temples. Among the Romans it was very frequently used, as, for example, in the Temples of Concord, Vespasian,

Fig. 8. Plan of the so-called Temple of Fortuna Virilis in the Forum Boarium at Rome. The black shows the part built of tufa: the hatching shows the harder travertine used at points where special strength was needed.

[p. 2.777] Faustina, and the so-called Temple of Fortuna Virilis in Rome. The main object of this plan was to give greater width to the cella (see fig. 8).

The last class named by Vitruvius is the Hypaethros, which appears to be an arbitrary class of his own. He describes the hypaethral temple as having ten columns at each end, and being dipteral along the flanks. Inside the cella are two tiers of columns, one above the other, supporting the roof, in the middle of which is an opening to the sky. As an example he gives the octastyle Temple of Olympian Zeus in Athens. The real fact is that the hypaethral temple does not form a separate category, as any of Vitruvius' last three classes might be hypaethral, the two tiers of columns being common in Greek peripteral temples, as, e.g., in the Parthenon, and in the great temple at Paestum, where some of the upper range of internal columns still exist.

It should be observed that Vitruvius' remarks about Greek temples must be accepted with great caution. He evidently knew very little about them, except perhaps some of the largest Ionic temples in Asia Minor. His ignorance on the subject is shown in many ways, and especially by his statement that the Doric style was unsuited and little used for Greek temples (see Vitr. 4.3, § § 1, 2). In studying Vitruvius' very interesting work, it should always be remembered that he was rather a practical architect than a learned antiquary, and that he had little or no personal knowledge of Greek buildings.

Vitruvius also gives different names to temples according to the number of columns on their fronts, namely:-- Τετράστυλος, tetrastyle, with four columns.

Ἑξάστυλος, hexastyle, with six columns.

Ὀκτάστυλος, octastyle, with eight columns.

Δεκάστυλος, decastyle, with ten columns.

A peripteral temple could not be less than hexastyle, nor a dipteral temple less than octastyle.

The sacred Hall at Eleusis, which was quite abnormal in plan, had a portico with twelve columns in front. It is very rare to find a Greek temple with an uneven number of columns at its ends. The second temple in point of size at Paestum has nine columns at each end, together with a central row of columns down the middle of the cella. The most probable explanation of this unusual arrangement is that the temple was dedicated to two deities, and therefore was divided longitudinally by a row of pillars. The great pseudo-peripteral Temple of Zeus at Agrigentum has seven engaged columns at each end. These are almost the only examples of Greek temples with an uneven number of columns at the ends. The number of the columns on the flanks varies very much, but is usually more than double that of the fronts. Thus, for example, the following temples--which are all Doric, hexastyle, peripteral--have on their flanks--Temple at Aegina and Temple of Nemesis at Rhamnus, 12 columns; Temple of Theseus in Athens, the so-called Temple of Hera at Agrigentum, and the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, 13 columns; great temple at Paestum, 14 columns; temples at Corinth and Bassae, 15 columns; Heraion at Olympia, 16 columns.

Of octastyle temples, the Parthenon, and the great Temple of Zeus at Selinus, have on their flanks, 17 columns; the Corinthian Temple of Olympian Zeus in Athens, 20 columns; the Ionic decastyle Temple of Apollo at Didyme had 21 columns.

The only other Greek decastyle temple was the Heraion at Samos: the number of columns on its sides has not yet been certainly discovered.

Vitruvius (3.3) gives the following list of names for the various classes of temple intercolumniations or spans, measured from column to column in the clear. It should, however, be remembered that this list refers only to late Greek or Roman temples, not to buildings of the best Greek period, about which Vitruvius seems to have known nothing. The figures in this list give the intercolumniations in terms of the diameters of the shafts at the lowest part.

| Πυκνόστυλος | ˙ 1 1/2 ˙ | Pycnostyle. |

| Σύστυλος | ˙2 ˙ | Systyle. |

| Εὔστυλος | ˙ 2 1/4 ˙ | Eustyle. |

| Διάστυλος | ˙ 3 ˙ | Diastyle. |

| Ἀραιόστυλος | {more than 3} | Araeostyle. |

The larger Greek temples were divided into different parts. The inner space within the front portico was called the πρόναος; that at the rear was the posticum (see fig. 5); the principal chamber, which usually contained the statue of the deity, was the cella or σηκός: it was frequently divided into a “nave” and “aisles” by two ranges of internal columns. In some cases, as in the Parthenon and the temple at Corinth, a chamber at the back was walled off from the rest of the cella: this was the ὀπισθόδομος; it was used as a treasure chamber. A similar chamber in the Temple of Apollo at Delphi formed an inner sanctuary, ἄδυτον: in it was placed the gold statue of Apollo, the mystic Omphalos, and other sacred objects which only the priests were allowed to approach.

One or more staircases were frequently introduced into the cella. In the Temple of Zeus at Olympia the stairs (ἄνοδος σκολιὰ) led to the ὑπερῷον, or gallery over the aisles, whence a good view was obtained of the colossal gold and ivory statue by Pheidias (see Paus. 5.10). In the so-called Temple of Concord at Agrigentum, the two stone staircases which led to the roof are still in perfect preservation. Similar staircases in the two other temples at Agrigentum still exist, though they are not so complete (see also fig. 5). In many cases, as in the Parthenon, these stairs appear to have been made of wood.

In the Temple of Concord (so called) at Agrigentum the doorways at a high level still exist, which gave access to the space between the wooden roof and the ceilings of the pronaos and posticum. In some temples a vestibule, prodomus, existed behind the pronaos (see fig. 6).

Stylobates and Steps.--The base or stylobate of a Greek temple consisted of two or more steps, the height of which was not in proportion to a man's stature, but was fixed by the height of the building. The usual number of steps in Doric temples was three, but a few temples, such as the so-called Theseum in Athens and the [p. 2.778]Heraion at Olympia, only had two. In the larger temples, such as the Parthenon, the height of the “riser” of the steps is too great for practical purposes of approach, and so smaller intermediate steps were introduced at certain places to give convenient access to the raised peristyle.

The cella floor is usually raised two or three steps above the peristyle. At Paestum the floor of the cella of the great temple is raised to the very unusual height of 4 ft. 9 in. above the top step of the stylobate. In many cases the central portion of the cella floor is slightly sunk below the level of the “aisles:” this was probably intended to receive any rain-water which descended through the open hypaethrum, or, in some cases, to form a shallow tank for water in order to correct the natural dryness of the air in temples which contained a chryselephantine statue, the ivory of which was thought to suffer from the want of some moisture in the atmosphere (Paus. 5.11). In the Temple of Zeus at Olympia the reverse was the case, the surrounding country being damp and marshy, and so the shallow sinking in front of Pheidias' statue was kept full of oil, which was also used as a lubricant for the ivory when it was cleaned by the official φαιδρυνταί. This receptacle was made of black marble with a kerb or rim of white Parian.

The paving of temples was usually formed of large slabs of stone or marble: those in the Parthenon are squares of white marble 1 foot thick and about 4 feet square. In some cases the internal floor was made of a fine hard cement, as, e. g. in the temple at Aegina, where the pronaos and the central portion of the cella are paved with cement coloured red. So also the Heraion at Olympia had in the cella a paving of red cement.

The pronaos of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, built 469-457 B.C., was paved with a curious early kind of mosaic, formed, not of squared tesserae, but of natural pebbles of different colours selected from the bed of the river Alpheus. These are set in a fine white cement on a thick bed of concrete. The design consists of Tritons and sea-monsters within a conventional border. This is almost the only example of mosaic of the Greek period that has been found, though mosaics of the Roman period in Greece are far from rare.

In many cases an open gutter, cut out of long blocks of stone or marble, was placed round the lowest step of the stylobate to carry off the rain-water which fell from the eaves of the roof. The water from the roof was discharged through lions' heads placed at intervals along the cymatium or top member of the cornice, after the fashion of a mediaeval gurgoyle. Vitruvius (3.5.15) recommends that only those lions' heads should be pierced which came over the centre of the peristyle columns, to diminish the amount of falling water that the rain could blow towards the cella wall, each column acting as a shelter. The other (unpierced) heads were merely for ornament. The rain--water from the gutters was carried in pipes or open channels to tanks which were built or cut in the rock at various places near the temple: several exist in the Acropolis of Athens close by the Parthenon.

The great Ionic temples of Asia Minor were in some cases raised on a lofty stylobate, consisting of many steps extending all round the building. The Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, dating from the time of Alexander the Great, was constructed with no less than fourteen steps leading up to its peristyle: this great height was, however, exceptional. The decastyle Temple of Apollo at Didyme had only three steps, and the erection of temples on lofty stylobates was rather a Roman than a Greek custom.

Roofs.--Greek temples were roofed with simply framed “principals” and strong rafters, covered with tiles of baked clay, or, in the more magnificent buildings, with slabs of white marble jointed and fitted with the closest accuracy, so that not a drop of water could penetrate. According to Pausanias (5.10), marble roof-tiles were invented by Euergos of Naxos. The magnificent group of buildings on the Acropolis of Athens were all roofed in this costly manner. Even the stone Temple of Apollo at Bassae was roofed with marble tiles, a fact which Pausanias specially records (8.41) as one of the chief glories of the building. In no part of a Greek temple was more elaborate care lavished than in the formation of these marble tiles (σωλῆνες, tegulae); each was “rebated” at top and bottom to give the closest possible fit, and each side joint was covered by an overlapping “joint-tile” (καλυπτήρ, imbrex), the edges of which were ground down to an absolute accuracy of surface. At the eaves the end of each joint-tile was covered by a καλυπτὴρ ἀνθεμωτός, antefixa, an ornament which usually was sculptured with a lotus or acanthus relief. In the temple at Bassae each joint-tile was worked out of the same block of marble as the adjacent roof-tile, involving an immense amount of labour and waste of marble.

Ceilings.--The peristyle, and in some cases, the pronaos and posticum, had ceilings under the wooden roof formed of great slabs of stone or marble decorated with a series of deeply-sunk panels or coffers (lacunaria), all worked in the solid, and ornamented with delicate enriched mouldings round the edge of each offset. With regard to the wider span of the cella, it is uncertain to what extent inner ceilings were constructed. Probably in some cases wooden ceilings with square lacunaria were used; in other cases the rafters of the roof and the underside of the marble tiles were left visible, as is shown by the fact that marble tiles have been discovered with traces of painted ornament on their lower surface. The whole visible woodwork, whether rafters or internal ceiling, was decorated with gold and colour, like the rest of the building. Vitruvius (4.2, 2) speaks of roof-panels painted blue by the wax encaustic process.

Screens.--Various parts of a Greek temple were usually shut off by elaborate bronze screens or grills which were frequently gilt. Thus, for example, in the Parthenon, tall bronze screens closed the intercolumniations of the pronaos and posticum. Another screen surrounded the chryselephantine statue of Athene, and the “aisles” of the cella were screened off in the same way from the central space in front of the statue. In some cases these metal screens rested on a marble plinth, but more commonly they [p. 2.779]were fixed by melted lead into the paving of the temple.

Doorways.--Even in cases where there was a polished marble door architrave, as in the Parthenon and the Propylaea in Athens, it appears to have been usual to fix an inner jamb-lining of wood. This wooden architrave and the valves of the doors were both covered with richly-worked reliefs in gold and ivory, at least in the richer temples. Descriptions of this costly decoration are given in the treasure lists of the Parthenon (see C. I. A. 2.708). The heavy gold plating and ivory reliefs on the doors of the Temple of Athene at Syracuse were stripped off by Verres, as Cicero states in his impeachment. This gold plating made the doors very heavy, and so they were hung, not on hinges, but on massive bronze pivots, which revolved in sinkings in the lintel and sill of the opening. Each valve, in the case of a large doorway, usually ran on a bronze wheel, the marks of which are plainly visible in the Parthenon and in many other temples, on the marble threshold and pavement.

Temple Treasuries (thesauri, θησαυροί).--In some temples, as e. g. the Parthenon and the early temple at Corinth, a special chamber, the opisthodomus, was cut off from the rest of the cella as a store-place for the rich treasures in gold and silver which belonged to the temple or had been deposited there as if in a bank. In the Parthenon the opisthodomus appears to have been fitted up with shelves and cupboards. Inventories of the Parthenon treasures cut on marble which still exist mention various objects as being on the first, second, or third shelf, if that is the true meaning of the arrangement according to ῥυμοί. Other portions of the Parthenon treasure were kept in the pronaos and in the cella, ἑκατόμπεδον or Παρθενὼν proper (see Newton and Hicks, Attic Inscriptions in the Brit. Mus., Part I.). In other cases, when there was no separate treasure-room, part of the pronaos or posticum was screened off from the central passage and used as a store-place.

In later times some of the most venerated temples, such as those at Delphi2 and Olympia, grew so rich in cups, tripods, statuettes, and other votive offerings made of gold and silver, that there was not sufficient room to hold them in the temple itself, and so a number of separate little treasure-houses were built within the sacred precincts. These were often named after various Greek states whose offerings were kept within them. At Olympia a long row of these thesauri have been discovered: in design they were like small temples, the cella having either a prostyle portico or a portico in antis.

Materials and Construction.--The earlier temples were chiefly built of stone, even in districts where marble was plentiful. Very coarse local stones were frequently used, but whether the stone was fine or coarse it was invariably coated with a thin skin of very fine hard cement, usually made of lime and powdered marble or white stone, mixed with white of egg, milk, or some natural size, such as the sap of trees. This beautiful substance, which was almost as hard, white, and durable as marble itself, is similar to the caementum marmoreum, the making of which is described at length by Vitruvius (7.3, § § 6-8). The use of this marble cement not only protected soft stone from the weather and made the temple look as handsome as if it had been built of real marble, but it also had the advantage of forming a good, slightly absorbent surface for painted decoration, which seems always to have been applied to Greek buildings. For this reason, even when the temple was built of solid marble, it was not uncommon to coat it with a thin skin or priming of marble dust cement for the use of the painter.

In some of the early stone temples, especially in Sicily and at Olympia, terracotta mouldings and enrichments of a very elaborate kind were used to decorate the building. In some cases the whole of the entablature was simply built in squared blocks of stone, and then wholly covered with a casing of moulded terracotta, very carefully jointed and fixed with bronze pins. These terracotta casings were painted with elaborate and delicate patterns in blue and red, brown and white ochres. [TERRACOTTAS] In other cases the mouldings of the entablature and the like were roughly cut in the coarse stone, and then the fine finished mouldings and enrichments were worked in the marble-dust cement which coated the whole stone-work.

By degrees marble came into use for building temples; at first in a very sparing way, being used only for the sculptured reliefs, and not always for the whole of those. In one of the temples at Selinus no marble is used in the building except a few small bits employed for the nude parts of the female figures in the metopes. All the rest of the sculpture is of the local limestone. At Bassae the use of marble is more extended; the whole of the sculpture and the roof-tiles are of marble. At Aegina the sculpture and only the lower courses of tiles were of marble. A further extension of its use was in the last Temple of Apollo at Delphi, in which the columns of the front were of marble, all the rest of the building (except the sculpture) being of local stone. The Alcmaeonidae of Athens were the contractors for this temple; and though their contract was only for stone, yet they were liberal enough to supply these marble columns for the front of the temple (see Hdt. 5.62). Lastly the whole temple from the floor to the roof was built of marble, and in the 4th century B.C. the great temples of Asia Minor were built of marble, even in cases where no marble quarries were at hand. Coloured marbles, though largely used by the Romans, were but little employed in Greek temples.3

In Athens the dark grey Eleusinian marble was used in some cases for steps, pavements, or plinths; and in the Erechtheum the main external frieze was made of this dark marble, ornamented with figures carved in white marble in half-relief, and attached to the ground with bronze pins. With this exception nothing but [p. 2.780]white marble was used in the Athenian temples after the Persian war, at least above the ground-line. The native limestone (πῶρος) was commonly used for foundations. Many different kinds of decorative materials were used: rosettes and other ornaments of gilt bronze were frequently attached to the eyes of the volutes of Ionic capitals, and in the centres of the panels of the lacunaria of the ceilings. Bits of coloured glass or enamels of brilliant tint were inlaid in the interstices of the plait-band ornaments of Ionic capitals and bases. The Erechtheum especially was enriched with bronze and enamel ornaments of many kinds. Rings of gold ornament decorated the bases of the Ionic columns of the Artemision at Ephesus, and we read of the joints in a temple wall at Cyzicus being marked with lines of gold inlay (see Pliny, Plin. Nat. 36.98).

In the marble masonry of the finest Greek temples extraordinary care was taken to fit each block closely to the next. Each block was first cut and rubbed to as true a surface as possible, and then, after it was set in its place, it was moved backwards and forwards till by slow grinding it was fitted with absolute accuracy to the block below it. The drums of the columns were ground true in the same way by being revolved on a central pin fixed in a wooden socket, which was let into the centre of the bed of the drum. Small projecting blocks of marble (ὦτα) were left by the masons, first to give a hold to the loops of rope while the drum was being raised to its place, and secondly these projections formed a sort of handle by which the great drum of marble could be made to revolve. Of course, with such perfect fitting as this, no cement or mortar of any kind was used, and with time and pressure the adjacent blocks seem in many cases to have, as it were, grown together, so that when a portion of the wall is thrown down a fracture will often run diagonally through two blocks of marble rather than separate the two at the joint. In the absence of cement great labour and much metal were expended in fastening each block with bronze or iron clamps and dowels, all carefully fixed with melted lead. Every block in the Parthenon, for example, is not only clamped to the adjacent blocks in the same course, but is fixed by upright dowels to the courses above and below,--a refinement of precaution, which to modern builders would seem quite needless; there being no side thrust, and the blocks being of such great size and weight as to be in no danger of any movement, except perhaps during an earthquake.

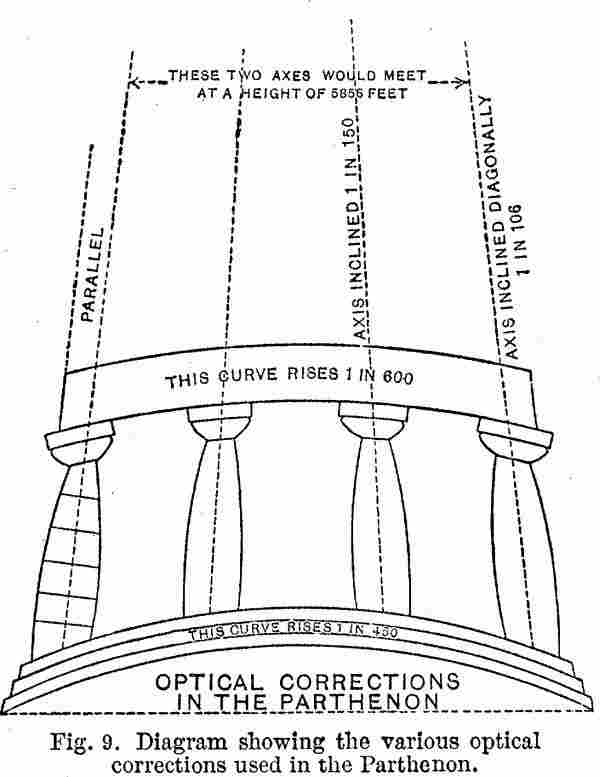

Optical refinements.--Nothing in the way of human workmanship can be more wonderful than the perfection and minute accuracy with which every part of a Greek temple of the best period was executed. The very elaborate system of curved lines and inclined axes, which the highly sensitive eye of the Greek thought necessary to the beauty of a building, shows, more clearly than anything else, how far superior to ours were the aesthetic perceptions and the delicately trained eyesight of the ancient Greek. The general principle of the optical corrections used by the Greeks is explained by Vitruvius, though he appears not to have been acquainted with all their refinements. He writes (6.2.1): “Acuminis est proprium providere ad naturam loci aut usum aut speciem detractionibus vel adjectionibus temperaturas efficere, uti, cum de symmetria sit detractum aut adjectum, id videatur recte esse formatum, in aspectuque nihil desideretur.”

A careful study of existing Greek temples, and especially of the Parthenon, has shown that the following classes of optical corrections were used.4

I. Entasis (adjectio) of columns (Vitr. 3.3.13): the lines of the shafts, instead of diminishing regularly from bottom to top, are slightly convex, giving a very delicate swelling to the central part of the shaft. A column formed with straight lines appears to get thinner than it ought towards the middle, owing to the effect of the light behind it, which appears, as it were, to eat into or encroach upon the column, especially midway between the top and bottom. This entasis is the only one of the many optical refinements of the Greeks which is used in modern buildings.

II. The columns at the angles of peripteral temples were made slightly thicker than the rest, and the intercolumniations at the angles were reduced. The object of this was to prevent the angle columns from appearing thinner than the others on account of their being seen against a brighter background than those which showed against the cella walls--a dark object always appears smaller against a bright ground, such as a sunny sky, than if seen with a dark ground behind it.

III. The main horizontal lines of the temple were formed slightly convex, in order to prevent an appearance of weakness and sinking in the middle. Thus the steps and floor of the stylobate, and the horizontal lines of the entablature, have a very slight and delicate curve, the rise varying, e.g. in the Parthenon, from 1/450 to 1/750 of the length.

IV. An inward slope of all vertical lines and planes to give an appearance of stability. The columns were not set upright, but all sloped inwards towards the building. The cella walls were built “battering;” that is, thicker at the bottom than at the top. Even the principal flat surfaces of the capitals and entablature were made so as to slope inwards.

V. In some cases when the point of sight is near, and the moulding high up, as with the capital of an anta, the chief planes of the moulding slope forwards instead of inwards, to correct the excessive foreshortening which otherwise would prevent the vertical flat surfaces from being seen from below.

A very interesting inscription has been discovered at Lebadea in Boeotia, giving the specification for the partial rebuilding of a temple there to Zeus. It gives many curious details about the construction of the building, and contains the following clause about the optical corrections which were to be used: τὰ δὲ ἄλλα ὅσα μὴ ἐν τῇ συγγραφῇ γεγράπται κατὰ τὸν κατοπτικὸν νόμον καὶ ναοποίκον ἔστω,--“as concerns other matters not written in the specification, let them be done according to the [p. 2.781]optical rules for the construction of temples” (see Choisy, Études Épigraphiques sur l'Architecture Grecque, p. 173 seq.).

Fig. 9 shows in a very exaggerated form the most important optical corrections in the Parthenon, as discovered by Mr. F. C. Penrose.

Fig. 9. Diagram showing the various optical corrections used in the Parthenon.

Each block of marble is worked accurately so as to form its proper proportion of these delicate curves, which, e. g. in the entablature, amounts only to a rise of 2 inches in 100 feet of length.

The general system of design in a Greek temple is very different from that of such a building as a Gothic cathedral. In the latter the module or unit of scale has some relation to the height of the human figure, and great size is gained by multiplying parts, not by merely magnifying the scale. In a Greek temple the module or unit is the diameter of the external columns,5 and a large peripteral temple may be exactly like a small one with all its parts magnified. Thus in the largest temples the doorway, magnified in proportion to the size of the columns, has no relation to the human height; and in details, such as the entablature, a large cornice will have no more members than a small one, but merely each member increased in size. Beautiful and unrivalled in execution as Greek architecture is, this want of adaptability, which comes from the use of a single external order only, is a very real practical defect.

Methods of Decoration in Greek Temples.

Sculpture.--In Doric temples the usual parts which were decorated with sculpture were the pediments or triangular gables at the ends: these usually contained groups of figures in relief or in the round. The metopes, or panels between the triglyphs over the architrave, were filled with reliefs: in some cases, as in the Parthenon, every external metope contained a relief; in other cases only, those on one or both ends. The celebrated Parthenon frieze (ζωοφόρος) was set within the peristyle at the top of the cella wall. At Bassae the frieze was inside the cella, over the “engaged” columns which projected from the side walls of the cella, and there were also sculptured metopes inside the peristyle. In Ionic and Corinthian temples, which had no triglyphs and metopes, a continuous sculptured frieze was usually carried along the main entablature. The Artemision at Ephesus was not only decorated with pedimental sculpture and an external frieze, but a number of its columns had their lower drums sculptured with life-sized figures in relief--the columnae caelatae of Pliny, Plin. Nat. 36.95. In addition to this some of the columns were set on square sculptured plinths. Even the older temple to which Croesus was a liberal benefactor had columns decorated with reliefs in the same way.

Some Greek temples, such as that at Bassae and the Heraion at Olympia, were constructed with a series of recesses separated by engaged columns along the side walls of the interior of the cella. These were designed to hold single statues of the deities. The celebrated Hermes of Praxiteles stood in one of the shrine-like recesses of the Heraion at Olympia. The more celebrated temples, especially those which stood on the site of some great agonistic contest--such as Delphi, Corinth, and Olympia--were crowded with votive statues, both inside the cella and in the portico and peristyle. At Olympia and Delphi, before the Roman spoliation, the statues in and around the temples must have been numbered by the thousand. A very large proportion of these were of bronze, in many cases thickly plated with gold. Even in Pliny's time the sacred periboli at Olympia and Delphi still contained fully 3,000 statues each (H. N. 34.36): and at the time of Pausanias' visit to Delphi they must have been more numerous still (see his long account of them 10.8-15, 18, 19, and 24). He names nearly 150 statues at Delphi as being worthy of special notice.

The principles of composition which were applied to the sculpture on Greek temples were mainly these:--In the pediments the interest of the motive usually converged towards the centre. In a continuous frieze the interest was more distributed; in the Parthenon frieze it culminates in the central group over the main entrance. In the metopes combats were favourite subjects, giving strongly-marked diagonal lines of composition, which formed a pleasant contrast to the vertical lines of the triglyphs. When a continuous frieze was sculptured with battle scenes, as is the case at Bassae, the composition formed a series of zigzag lines which gave a continuous flow of action. In all cases great care was taken by the Greek sculptor to make his work harmonise with its architectural surrounding, very unlike modern sculpture on buildings, which usually has no more relation to its position than if it were a mantel-piece ornament.

Painting.--Rich painted decoration in brilliant colours seems to have been used to ornament all the Greek temples. Even the sculpture was [p. 2.782]painted, either wholly or simply set off by a coloured background, and enriched with borders and other patterns on the drapery. Accessories, such as weapons, trappings of horses and the like, were usually of gilt bronze. The mouldings of the entablatures, capitals, and other parts were all picked out in red, blue, and gold, with very minute and elaborate patterns painted on the larger members, in the coffers or panels of the lacunaria, and on the cross-beams of marble which supported the great ceiling slabs over the peristyle. Certain enriched mouldings, such as the “bead and reel,” appear to have been nearly always gilt, and in almost all the patterns of the richest temples thin bands of gold were used to separate and harmonise the brilliant tints of colour.

The interior of the temple walls was often covered with large paintings of figure subjects: in the Parthenon, for example, the pronaos contained a painting of the rock Aornus and the fissure which drew into it birds flying over it. In the cella were portraits of Themistocles and Heliodorus (see Paus. 1.2, 37): and Pliny (Plin. Nat. 35.101) records that in the portico of the Parthenon was a painting by Protogenes of Caunus, representing the sacred triremes Paralus and Ammonias. Similar pictures decorated the internal walls of most Greek temples.

Votive shields of gilt bronze were frequently attached to the architraves of Greek temples, as was the case with the Parthenon, the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, and that of Apollo at Delphi (Paus. 5.10, 2, and 10.19, 3). Part of the Parthenon architrave was decorated with hanging wreaths or festoons of flowers worked in bronze. The positions of these and of the shields are still marked by the stumps of the bronze pins which fixed them to the marble. In some cases sets of votive armour and weapons were hung to the cella walls, both inside and out, as well as ex-votos of many other kinds.

Orientation.--Greek temples are usually placed with their axes east and west: the front is commonly towards the east. There are, however, exceptions to this rule: the Temple of Apollo at Bassae stands north and south, but has on its east flank the unusual feature of a side door, placed near the statue of the god--possibly to allow the rays of the rising sun to strike the statue of Apollo, who was there worshipped as the deliverer from a fearful pestilence which had devastated the neighbouring city of Phigaleia, about the middle of the 5th century B.C.

Greek temples of the historic and autonomous period were built in two styles, Doric and Ionic. The Corinthian style belongs to a later period.

Doric Temples.--In the mainland of Greece, in Magna Graecia, and in Sicily, the Doric style was the first to be developed. Almost all the existing Greek temples in these countries are Doric. The chief archaisms or points of difference between the early and the fully-developed Doric temples are these:--In the older examples the columns are proportionally shorter and thicker, the architrave is heavier, the intercolumniation is closer, the diminution of the shafts of the columns is proportionally greater; the abacus of the capital is shallow and wide-spreading, the echinus of the capital is formed with a more bulging curve. Entasis and other optical refinements are used in a limited and imperfect way. The shafts of the columns are as far as possible monolithic; marble is used very sparingly or not at all.

The largest number of early Doric temples which still exist are in Sicily; at Syracuse, Agrigentum, Selinus, and Segesta. Another example of very early date is the temple at Corinth. Of the later, fully-developed Doric, the chief examples are in Athens, and at Bassae in Arcadia.

The temple in Aegina occupies an intermediate position in point of date. With regard to the oldest existing temples it is impossible to fix any exact date; there is, however, little doubt but that the two earliest temples at Selinus, and one in Syracuse, of which very little more than two columns now exist, are not later than the end of the 7th century B.C. The latest Greek Doric temple of which any remains still exist is probably that of Athene Alea at Tegaea, which was designed by Scopas in the early part of the 4th century B.C. (see Paus. 8.45).

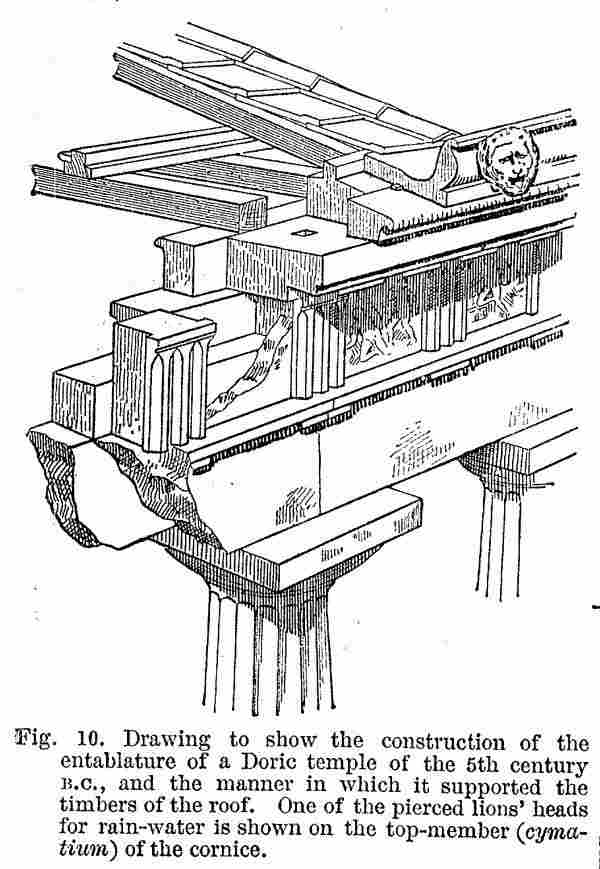

The main characteristics of the Doric style are these--columns without bases, with shallow flutings not separated by a fillet. The capital consists of a square abacus resting on a slightly curved cushion-like member, which is called the ἐχίνος (echinus), from its resemblance to the shell-fish popularly called a sea-urchin. The architrave which rests on the abaci of the columns is plain, without any sinkings or fasciae, such as are used in the Ionic style. Above the architrave comes the frieze, which is divided into triglyphs (τριγλύφοι), and metopes (μετὰ ὀπάς). As Vitruvius quite correctly points out (4.2), the Doric order is a survival in stone of a primitive method of construction in wood.

The grooved triglyphs were copies of the ends of the tie-beams of the roof principals. The holes in the upper course of the wall in which the tie-beams rested were called (ὀπαί), and hence the intermediate spaces were the μετ᾽ ὀπαί, metopes. In the early wooden buildings the metopes were frequently left open to admit light and air (see Eur. Iphig. 113); and in domestic buildings they probably served as an exit for the smoke from the central hearth (ϝεστία) in the middle of the μέγαρον or hall. In later times the metopes were closed and decorated with painting or sculpture.

Above the Doric frieze was the cornice, the third and last part of the entablature: this was very simple, consisting mainly of a deep overhanging block with a plain flat surface called the corona, and on its soffit or under-side a series of mutules, covered with three rows of three circular projections, guttae. The mutules were survivals in stone of the ends of the small rafters, which showed above the ends of the tie-beams. The top member of the cornice, cymatium, was originally the upturned edge of the eaves' tiles, and was pierced at intervals to allow the rain-water to escape (see fig. 10).

The description already given of the plans and general arrangement of Greek temples applies to those of the Doric style, except that no Doric decastyle temple appears to have been built, though the dodecastyle portico of the Hall of the Mysteries at Eleusis had columns of the Doric order. This, however, was not, as is mentioned [p. 2.783]above, a temple, but rather a great hall or μέγαρον.

Fig. 10. Drawing to show the construction of the entablature of a Doric temple of the 5th century B.C., and the manner in which it supported the timbers of the roof. One of the pierced lions' heads for rain-water is shown on the top-member (cymatium) of the cornice.

The method in which Greek temples were lighted is a rather difficult problem: windows were not used till Roman times, and it appears fairly certain that some form of opening in the roof (ὀπαῖον, hypaethrum) was the usual way in which light was admitted into the cella.6 Prof. Cockerell found at Bassae one of the marble roof-tiles which had formed the border to some such opening. A raised rim or kerb was worked on the tile so as to prevent water dripping from the roof into the interior. The existing circular hypaethrum in the dome of the Pantheon in Rome shows the great aesthetic beauuty of such a method of lighting; the inconvenience from rain falling on to the marble paving is comparatively slight.

After a long-established custom of sacrificing on altars in the open air, there was probably a survival of sentiment in favour of having some part of a temple sub divo. Both religious and poetical notions have almost always closely associated the notion of the visible sky with the abode of God. Support is given to the hypaethral theory of lighting by a curious passage of Justin, 24.8, who relates that when Delphi was attacked by the Gauls the Pythia and the priests cried out that they saw Apollo descending through the roof opening of the temple--“eum se vidisse desilientem in templum per aperta culminis fastigia.” An ingenious theory was invented by Mr. James Fergusson, that the hypaethrum or ὀπαῖον was not over the central space of the cella, but that there was one on each side over the aisle galleries; the light being admitted sideways, through windows like those of a mediaeval clerestory (see Fergusson, The Parthenon, 1883). There is, however, little real evidence to support this theory, and the explanation would not apply to those numerous temples which had no “aisles” or internal columns to support a gallery.

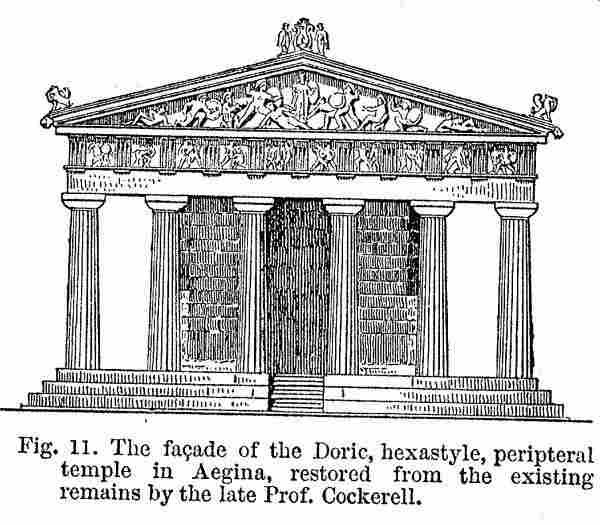

The general appearance of the façade of a Doric temple is shown in the annexed figure (No. 11) of the temple at Aegina, as restored by

Fig. 11. The façade of the Doric, hexastyle, peripteral temple in Aegina, restored from the existing remains by the late Prof. Cockerell.

Cockerell from the existing remains. The pediment has fallen, and the sculpture is now at Munich, but most of the columns are very perfect. The date of this temple is probably about the middle or latter part of the 6th century B.C.

It should be observed that some temples of the Doric style had internal columns of a different order. The columns in the opisthodomus of the Parthenon were probably Ionic. At Bassae the internal columns of the cella were Ionic, and at Tegea it is probable that the columns of the pronaos and posticum were Ionic, while those inside the cella were Corinthian (see Paus. 8.45.3 seq.). The Propylaea of the Athenian Acropolis has a similar combination of the Doric with the Ionic style.

In the earlier temples all the columns seem to have been Doric, as we see in the great temple at Paestum, where the internal columns still exist.

The so-called Temple of Demeter--or, more correctly, the Σηκὸς μυστικός--at Eleusis, was a completely different building from ordinary Greek temples, as it was a great hall of meeting for those initiated into the mysteries of Demeter, Kore, and other Chthonian deities. It has recently been excavated and plans of the successive structures made with great care and skill by Dr. Dörpfeld (see Fouilles d‘Éleusis, Athens, 1889: cf. also Paus. 1.38).

The latest building was a large square hall containing six rows of seven columns each. On three sides, there were two doorways, six in all. The fourth side, which was built against the scarped face of the hill, had no entrance on the ground--floor. It appears probable that the building was in two stories.7 On the ground-floor eight tiers of step-like seats were [p. 2.784]placed against all four walls; the lines of seats being broken only by the doorways. In front was the great Doric dodecastyle portico built by Philo in the 4th century B.C. The plan of the whole building is Oriental rather than Greek in character. It closely resembles the “Hall of the Hundred Columns” in the palace of Darius and Xerxes at Persepolis. Dr. Dörpfeld discovered remains of two earlier and smaller buildings of similar plan on the same site.

The sacred temenus was approached through an inner and an outer propylaeum; the larger, outer one, of Roman date, is a close copy of the propylaeum of the Athenian Acropolis. In front of the outer gateway was a small amphiprostyle temple of Artemis, some remains of which still exist. (See Bull. Cor. Hell. 1.1885.)

The following are the principal Doric temples of which remains still exist, arranged as nearly as possible in chronological order:-- Syracuse, Island of Ortygia, Temple of Artemis, hexastyle, very archaic, scanty remains. 7th century B.C., or even earlier.

Selinus (Sicily), three temples on the Acropolis, all hexastyle, with 19, 14, and 13 columns respectively on the flanks, of local limestone, very early in style. 7th cent.

Syracuse, Ortygia, Temple of Athene, hexastyle, now built into the cathedral. Late 7th cent.

Selinus, great Temple of Zeus in the Agora (see fig. 7), octastyle, with 17 columns on the flanks: never finished. 7th cent.

Corinth, hexastyle, with 15 columns on the flanks; only 7 columns now remain. Late 7th cent.

Segesta, Sicily, hexastyle, the peristyle perfect, but the cella wholly gone, probably unfinished. 6th cent.

Agrigentum, Sicily, the great Temple of Zeus, heptastyle, with 14 columns on the flanks, pseudo-peripteral, slight remains. 6th cent.

Aegina, hexastyle, with 12 columns on the flanks; very perfect (see fig. 11). 6th cent.

Paestum, Lucania, the so-called Temple of Poseidon (see fig. 5), hexastyle, with 14 columns on the flanks, very perfect. 6th cent.

Delphi, Temple of the Pythian Apollo, hexastyle, peripteral; designed by Spintharus of Corinth soon after the burning of the previous temple (the fourth on that site) in the year 548 B.C. Second half of the 6th cent.

Agrigentum, Sicily, three hexastyle temples, two of them very perfect. Late 6th or early 5th cent.

Selinus, the middle temple on the Agora. c. 500 B.C.

Assos, Asia Minor, hexastyle, with sculpture on the architrave, very rude in style, scanty remains. c. 480 B.C.

Athens, so-called Temple of Theseus, hexastyle, with 13 columns on the flanks, very perfect. c. 465 B.C.

Olympia, Temple of Zeus, built by Libon of Elis, hexastyle, with 13 columns on the flanks; little remains standing. 469-457 B.C.

Olympia, the Heraion, a mixture of many dates, mostly destroyed, hexastyle, with 16 columns on the flanks.

Athens, the Parthenon, octastyle, with 17 columns on the flanks, still fairly perfect, built by Ictinus. 450-438 B.C.

Selinus, hexastyle temple in the Agora. Middle of 5th cent.

Sunium, Attica, hexastyle, a few columns only remain. Middle of 5th cent.

Bassae, Temple of Apollo Epicurius, hexastyle, with 15 columns on the flanks, built by Ictinus, still fairly perfect. c. 440 B.C.

Rhamnus, Attica, Temple of Nemesis, hexastyle, peripteral; and Temple of Themis, cella with portico in antis, and walls of polygonal masonry, a late survival of this early method of building (see fig. 3). Middle of the 5th century.

Eleusis, the Hall of the Mysteries, with a dodecastyle portico, which is a later addition. c. 440-220 B.C.

Tegea, Temple of Athene Alea, built by Scopas, hexastyle, with 13 columns on the flanks; date soon after 393 B.C.

Paestum, enneastyle temple, and a small hexastyle temple, probably built by native Lucanian architects in the 4th cent. B.C.

Ionic Temples.--The main points in which the Ionic order differs from the Doric are these:--The columns have bases, and the capitals are decorated with volutes and a moulded abacus, instead of the simple echinus and plain abacus of the Doric style. The whole entablature is more elaborate, the architrave being divided into receding planes or bands (fasciae), and the members of the cornice more numerous and elaborate. The small cubical projections called dentils, which are set closely along the fully-developed Ionic cornice, are one of the chief characteristics of the style, though not always present in Athenian examples. Besides these important differences of design, the whole character of an Ionic temple is more light and graceful than that of a Doric building. Thus Vitruvius fancifully compares the Doric order to the proportions of a man, and the Ionic to those of a woman (Vitr. 4.1, § § 6, 7). The columns are more slender, and so in proportion taller; the diminution and entasis are less. The intercolumniation, or distance from column to column, is wider, giving a lighter effect to the whole building. The flutes on the columns are separated by flat strips or “fillets,” and the members of the mouldings are much more largely enriched with carving.

No very early example of an Ionic temple is now in existence; but some very primitive Ionic capitals, which have recently been found deeply buried on the Athenian Acropolis, show that even in Attica the Ionic style, though in an undeveloped form, was used before the Persian invasion. The earliest Ionic temple in Greece proper, which existed till modern times, was a very graceful little building on the Ilissus, close by Athens, but this was destroyed about a century ago. Luckily it is well illustrated in Stuart and Revett's valuable work on Athens. It was a tetrastyle, amphiprostyle building, and from some of its details, especially the absence of dentils in the cornice, seemed a sort of link between the Doric and Ionic styles. It was probably built soon after the Persian invasion, about 475 B.C. The somewhat similar little Temple of Nike Apteros on the Acropolis, which has been carefully rebuilt and is now in a very perfect state, belongs to a rather later date, probably about the middle of the 5th century B.C. It is a mere shrine for a single statue, the cella being little over 12 feet square; and it possesses the remarkable peculiarity of having no front wall to the cella, but only two square pilasters to carry the architrave (see fig. 4). The open end of the cella was closed by a bronze screen fitted in between the pilasters and the antae.

Large and magnificent as are the great Ionic temples of Asia Minor, none of them can approach the beauty of the Athenian Erechtheum, either in delicate richness of detail or [p. 2.785]in minute perfection of workmanship. The Erechtheum, which stands to the north of the Parthenon, was rebuilt towards the end of the 5th century on the site of a very primitive temple of Athene Polias, which was burnt by the Persians in 480 B.C. It is a very complicated building, containing a group of many different shrines, and is quite unlike any other Greek temple. The main cella, which had a hexastyle portico towards the east, was subdivided by cross walls, and floors in several different chambers at various levels. Owing to this cella having been gutted to make it into a Christian church, the original plan is now a matter of some doubt. All that is certainly known is that some part, probably the eastern portion of the cella, was the shrine of Athene Polias, and contained a very sacred ancient ξόανον or wooden statue of the goddess. This statue is referred to in the official title of the temple as given in an existing inscription of the year 409 B.C., when the building was still in progress; the title is ὁ νεὼς ὁ ἐμ πόλει ἐν ᾧ τὸ ἀρχαῖον ἄγαλμα. Another part of the temple was called the Ἐρεχθεῖον, or shrine of Erechtheus, the mythical ruler of Athens, whose presence was symbolised by a living snake which was kept in the building (Hdt. 8.41, and Plut. Themis, 10). A third portion of the cella was the Κεκρόπειον or shrine of Cecrops. The building or its temenus also contained the spring of salt water and the olive-tree which were supposed to have been produced by Poseidon and Athene during their contest for the sovereignty of Attica (see Pausanias, 1.26.5 seq.). On the north of the cella is a very beautiful tetrastyle portico, at a much lower level than the eastern portico: in a vault under the portico floor are traces of the salt spring and the marks made by Poseidon's trident--σημεῖον τῆς τριαίνης--which were shown to Pausanias. On the opposite or south side of the main cella is the well-known Caryatid portico, supported by six graceful female figures, one of which is now in the British Museum. The entrance was by a side door in this little porch, leading down by a small flight of steps to the lower level at the west end. In the west wall a doorway gave access to a long sacred enclosure called the Πανδρόσειον in honour of Pandrosos, the one faithful daughter of Cecrops. In this court probably stood the sacred olive and an altar to Zeus Herkeios (sée Dionys., quoting Philochorus, de Deinarcho, 3). The three windows, which till recently existed in the west wall of the cella over the door, were insertions of a late date, probably of the time of Constantine, when the temple was made into a church. The apse, which was then built at the other end, unfortunately caused the destruction of the east portico, and in fact the whole building was gutted to make it into a single chamber.

The Erechtheum is richer in detail than any other Ionic temple, and is also quite alone in the minute delicacy of the execution of all its ornaments and mouldings. The capitals were decorated with a band of lotus pattern below the necking: the volutes were enriched with ornaments of gilt bronze, and delicate plaited mouldings, both on the capitals and bases, were inlaid with bits of jewel-like enamel. All the mouldings and reliefs were decorated with gold and colour. The whole work was extraordinarily elaborate and costly, and so took many years to execute. It appears not to have been completely finished till after the close of the Peloponnesian war. A very interesting inscription, with a report of its exact state in 409 B.C., is now in the British Museum (see Newton and Hicks, Greek Inscriptions in British Museum, i. p. 84).

The following is a list of the chief Ionic temples of which some remains still exist:-- In Greece proper:--

Athens: the temple of Nike Apteros and the Erechtheum on the Acropolis.

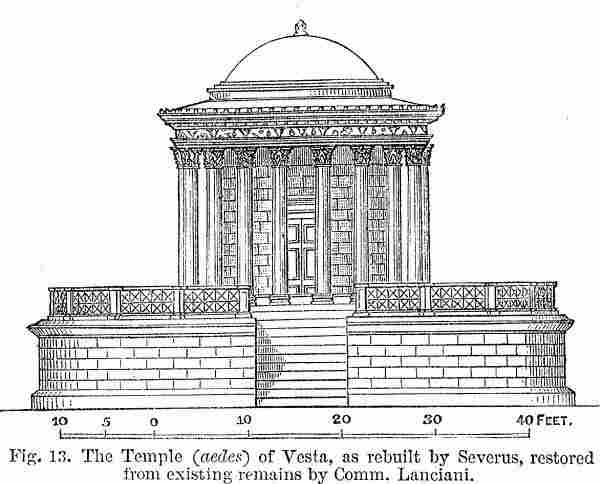

Olympia: the circular Philippeion, with 18 Ionic columns outside, and, inside the cella, engaged columns of the Corinthian order: similar in plan to the Roman Temple of Vesta shown in fig. 13.

In Asia Minor:--

Sardis: temple of Cybele, octastyle, with columns 60 feet high, of which only three remain, date about 500 B.C.

Xanthus in Lycia: Heroon of unknown dedication, a small tetrastyle, peripteral building on a lofty podium. Its sculpture is now in the British Museum. The date is doubtful, but it is probably not earlier than c. 400 B.C.

The Troad: Temple of Apollo Smintheus, octastyle, pseudo-dipteral, with very close (pycnostyle) intercolumniation. Most of the existing building seems to date from a period probably about 400 to 350 B.C.

Samos: Temple of Hera, decastyle, dipteral (see Paus. 7.4, and Vitruv. vii. Praef. 12). The existing temple is of the 4th cent. B.C. An earlier temple on the same site was built in the 7th cent. B.C. by Rhoecus of Samos; Herodotus mentions it as the largest temple he had seen (see 3.60, 2.148, and 1.70). The existing remains were first excavated by the Dilettanti Society in 1812. (See Antiq. of Ionia, i. p. 64; and Bull. Cor. Hell. iv. p. 383.)

Magnesia ad Maeandrum: Temple of Artemis Leucophryne, hexastyle, pseudo-dipteral, built by Hermogenes about 350 B.C. (See Vitruv. vii. Praef. 12.)

Teos: Temple of Dionysus, hexastyle, also built by Hermogenes about 350 B.C. (See> Vitruv. vii. Praef. 12; and 4.3, 1.) At 3.3, 8 Vitruvius mentions this temple as an example of eustyle intercolumniation. He goes on to say that its architect Hermogenes was the first to invent the pseudo-dipteral plan for a hexastyle temple by omitting the second (inner) range of columns, and so giving a wider ambulatory round the cella for shelter from rain for a crowd of people. (See Antiq. of Ionia, Part 4.1881.)

Priene: Temple of Athene Polias, hexastyle, very similar to the temple at Teos; it was built in the second half of the 4th cent. B.C. and was dedicated by Alexander the Great, as is recorded in the following inscription, which was discovered during the excavations of the Dilettanti Society:--Βασιλεὺς Ἀλέξανδρος ἀνέθηκε τὸν ναὸν Ἀθηναίη Πολίαδι.

Branchidae near Miletus: Temple of Apollo Didymaeus; decastyle, dipteral (see fig. 6). This and the temple at Samos were the only two Greek decastyle temples. That of Apollo Didymaeus seems never to have been completed. Vitruvius (vii. Praef. 16) mentions it as one of the four greatest temples of the Greeks, and that its architects were Paeonius of Ephesus and Daphnis of Miletus, about 350 B.C. Pausanias (7.5) says that, though unfinished, it is one of the wonders of Ionia. According to Strabo, p. 634, it was left roofless on account of its excessive span. (See Gaz. des Beaux Arts, xiii. p. 497, and 14.1876.) [p. 2.786]

Ephesus: Temple of Artemis (Artemision), octastyle,

dipteral, built during the reign of Alexander the

Great, 356-323 B.C.

In many respects this last was the most magnificent and celebrated of all Greek temples; the last temple built on the site ranked as one of the seven wonders of the world. It should, however, be remembered that the great size of the Artemision was a very important factor in its celebrity. In point of beauty of workmanship and minute refinement of detail it was far surpassed by the earlier Greek temples, such as the Parthenon and the Erechtheum. Between the 7th century B.C. and the time of Alexander the Great three successive temples were built on the same site. 1. The original temple built by Theodorus of Samos, the partner of Rhoecus, who was architect of the Heraion in Samos, probably about the year 630 B.C. 2. The temple which was begun by Chersiphron and finished by his son Metagenes about the end of the 6th century B.C. This temple was burnt by an incendiary, named Herostratus, the night when Alexander the Great was born, in 356 B.C. 3. The last temple built during the reign of Alexander was designed by his favourite architect Dinocrates. (See Pliny, Plin. Nat. 36.98; and Vitr. 10.2, § § 11, 12; vii. Praef. 12; and ii. Praef. 1-4). It should be observed that much confusion exists in the statements of Vitruvius, Pliny, and other authors as to the architects of the temple, owing to their not distinguishing clearly between the three successive buildings.

Considerable remains of the last temple, and pavements and foundations of the two earlier buildings, were discovered in the years 1870-6 by Mr. Wood; but unfortunately no satisfactory account or plan of his discoveries has been published. Mr. Wood discovered after long search that the Artemision, surrounded by its extensive temenus, stood, not within the city of Ephesus, but nearly a mile outside the Coressian gate. It had eight columns on the fronts, and probably twenty on the flanks: the stylobate, which consisted of no less than fourteen steps, measured at the lowest step about 418 by 240 feet. The columns were 56 feet high, and about 6 feet in diameter above the base. As has been already mentioned, some of the columns and their pedestals were enriched with sculpture, as were also the antae, of very varying degrees of excellence, some being well designed and graceful in motive, while other reliefs are extremely coarse and clumsy. None of the sculpture is remarkable for any high degree of finish or delicacy. The main entrance from the pronaos led, not directly into the cella, but into a large vestibule, part of which was probably shut off for use as a treasury. The temple was enormously rich in statues and votive offerings of all kinds in gold and silver; its doors were most magnificently decorated with plating of gold and ivory. A fragment of one of the bases of the main order, now in the British Museum, has remains of an ornament of pure gold fixed with lead between the double tori. The inside of the cella was decorated with a large mural painting of Alexander Ceraunophorus by Apelles and many other pictures, and contained a large number of fine statues by Scopas, Timotheus, Leochares, and other sculptors of the Asia Minor School. The temenus was very large, enclosed by a massive wall, and planted with groves of trees. It formed one of the most sacred sanctuaries of Asia Minor, and was the resort of great numbers of men who were flying from punishment for some misdeed. By degrees the bounds of the asyloum or sanctuary were enlarged, until they not only extended up to the walls of Ephesus, but even included part of the city, which thus became the resort of evil-doers. and was a great source of trouble to the citizens. Augustus therefore restricted the limit of the space which had the privileges of asylum.

The British Museum also possesses some very interesting fragments which belonged to the second temple, begun about the middle of the 6th century, to which the Lydian king Croesus was a liberal benefactor. These fragments show that the earlier temple had some of its columns decorated with life-sized reliefs after the same fashion as the last building. Some of these were given by Croesus, whose name and dedication were inscribed on the upper torus of one of the bases, some fragments of which are now in the British Museum. One remarkable peculiarity of this 6th-century building was that the large cymatium, which formed the top member of the main cornice, was decorated with figures in relief, which can have been hardly visible owing to their small scale and great height from the ground. See A. S. Msurray, Journ. of Hell. Sltudies, vol. x. p. 1 seq.

Graeco--Roman Temples.

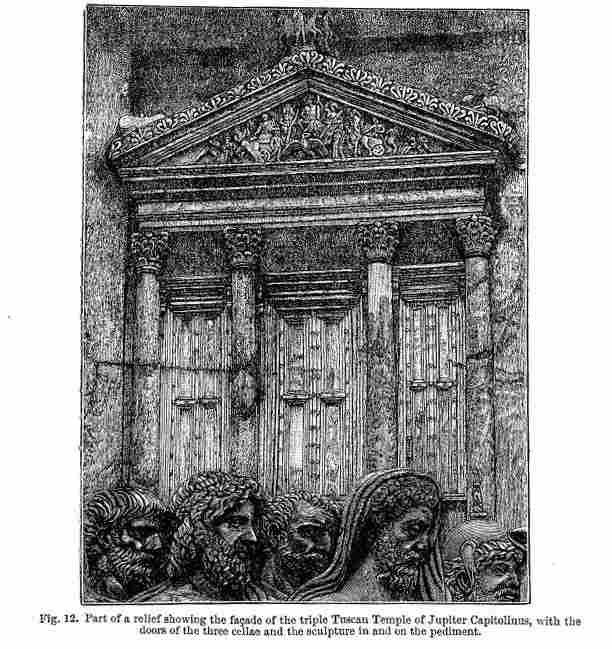

There are also two very magnificent Ionic temples in Asia Minor which date from the Roman period: these are at Aphrodisias in Caria, and at Aizani in Phrygia; both are octastyle, pseudo-dipteral buildings, with fifteen columns on the flanks. The elaborate, but somewhat coarse and extravagant, sculptured ornaments show that the date of these two very similar temples is probably not earlier than the 1st or 2nd century A.D. Each was surrounded with an extensive peribolus wall, within which a smaller space is enclosed by an open porticus or cloister; in the centre of this the temple itself stands. The temple at Aizani is remarkable for having a fine vaulted crypt under the cella floor, twenty-eight feet wide and fourteen feet high, probably used as a treasure chamber. (See Le Bas, Voyage Arch. dans la Grèce, &c. ed. Reinach, 1888; Texier and Pullan, Asia Minor, 1865; and the various treatises published during the last hundred years on The Antiquities of Ionia by the Dilettanti Society, vols. i. to iv. See also Newton, Travels in the Levant, 1865, and History of Discoveries at Halicarnassus, &c., 1862.)