.

1. Greek.

The word χορὸς in Greek signifies both a place for dancing (Hom. Od. 8.260; cf. εὐρύχορος and καλλίχορος) and the collection of dancers, but is more especially confined to the latter. In early times we find harvest festivals and weddings (Hes. Scut. 282) celebrated with bands of dancers (Hom. Il. 18.567). There is a detailed picture of young men and maidens dancing on the shield of Achilles (Il. 18.590 ff.). Another kind of chorus mentioned in the Iliad is the paean the Greeks sang as they marched to the ships after the death of Hector (Il. 22.391). It is to be remarked that in early times the song and the dance were assigned to different persons.

But it is especially in the service of the gods, and most of all in that of Apollo and Dionysus (cf. Dem. Mid. p. 530.51), that bands of dancers appear prominently. In religious ceremonies, poetry, music, and dancing were all united; and the strong impulse of the Greeks to give expression to their feelings led to the dance being, as all artistic dancing ought to be, of a more or less imitative nature. “It is the imitation of words by gestures (σχήμασιν) which has developed the whole art of dancing,” says Plato (Legg. 7.816 A; cf. Ath. 1.15). There were dances of the Curetes in Crete in honour of Zeus (Hes. Fragm. 91, ed. Didot), and in very early times dances in the worship of Apollo at Delos (Hom. Hymn. Apoll. Del. 249); but dance and song were first fully developed by the Apolline religion of Delphi, which was the guiding spirit and good genius of Dorian life. And the chorus was very suitable to the Doric character, according to which everything was public and collective, and which so strenuously demanded subordination of the one to the whole. But the choruses of the Dorians, performed to the music of the cithara, were most of them stately and measured, partaking much of the nature of gymnastic and military exercises (cf. Ath. 14.628) [GYMNOPAEDIA, PYRRHICA]; though the hyporchema, introduced into Sparta from Crete by Thaletas, was a spirited song and dance, performed to the music of the flute as well as of the cithara. [HYPORCHEMA] The Doric chorus was quadrangular, and analogies are found between it and the divisions of infantry (Müller, Dor. 3.12, 10). There were choruses of boys, men, and old men at the different Spartan festivals (Plut. Lyc. 21); and the matrons and maidens danced likewise (ib. 14); choruses of youths and maidens combined being called ὅρμοι (Lucian. de Salt. § 12). We must not fail, however, to remember, as Grote (chap. 29) warns us, that the term “dance” is to be taken in a wide sense for “every variety of rhythmical accentuated conspiring movements or gesticulations or postures of the body, from the slowest to the quickest.” For Sparta the Doric choral style was fixed by Alcman, and remained unaltered during three centuries. Further it is to be noticed that as the chorus was much developed at the same time in Argos, Sicyon, and other parts of Peloponnesus, the Doric dialect came to be regarded as the artistic dialect for choral song (cf. Curtius, Hist. of Greece, 2.83, Eng. trans.), and was used by all choral writers, whether Aeolian or Ionian, being retained in the language of the chorus even in Attic tragedy.

But in the Apolline religion beside Apollo stood Dionysus, the god of the peasantry, to whom the dithyramb was sung by the votary “when all-ablaze in soul with wine's thunder” (οἴνῳ συγκεραυνωθεὶς φρένας), as Archilochus says (Fragm. 72, ed. Bergk). Originally the dithyramb was the spontaneous song, telling the tale of Dionysus and his fortunes, which the chorus, which represented itself as Satyrs and others of his faithful attendants, guided by its leader (ἔξαρχος), sang to the music of the flute, as it danced the while round the altar of the god. [DITHYRAMBUS] The Satyrs were half goats (τράγοι), their song was the “goat-song” (τραγῳδία); and they were originally the sole performers in what afterwards became the elaborate tragedy. But there was another sort of chorus belonging to the old phallus cult which, [p. 1.420]under the guidance of its leader, sang phallic songs and danced in revel through the roads, with faces smeared with wine-lees, in the worship of Dionysus, “the jolly god,” the friend of love and wine. This was the wild song of the revel (κωμῳδία), and the origin of Greek comedy. Thus the chorus was the foundation of the two main kinds of Greek drama (Aristot. Poet. iv. 14). But as the word “chorus” in connexion with the ancient Greeks most naturally suggests the chorus in the developed forms of the drama, it is to the antiquities of the chorus in this sense that we must confine the present article, referring the reader for information on the dithyramb to the special article on the subject ; as to the manner in which the original chorus developed into the drama, to the articles COMOEDIA and TRAGOEDIA; and for the various kinds of figures (σχήματα) and special technical details of dancing, to the article SALTATIO

It is practically to the chorus of the Attic dramatists that we have to confine our remarks; and they may be conveniently arranged under the following heads:--

1. Number of Choreutae.

The circular dithyrambic chorus, as systematised by Arion for public exhibition in the city, consisted of 50 members (Simonides, 147 (203), ed. Bergk). The early tragic chorus consisted of 12, and is said to have been raised by Sophocles to 15 (Suidas, (Σοφοκλῆς). It has been supposed accordingly that the dithyrambic chorus of 50 was first arranged in a quadrangular form, which required only 48, and afterwards was divided into four choruses, one for each of the dramas of a tetralogy. Pollux (4.110) declares that up to the production of the Eumenides the tragic chorus consisted of 50, but that the people were so frightened at so many horrible figures that thereafter the number of the chorus was lessened. But this is a mere story, invented to account for the change of numbers. Again it was from the country dithyramb, not from the city dithyramb as organised by Arion, that the drama arose: this latter is to be regarded as the elder sister rather than as the parent of the Attic drama; and in the country dithyrambic chorus we have no evidence how many choreutae took part. At any rate, in the chorus of Attic tragedy there were originally 12 and afterwards 15; and where 14 are mentioned (e. g. in Tzetzes, Prol. ad Lycophr. 254, Müller), the coryphaeus is omitted. Whether the same choreutae took part in all four plays of a tetralogy or not, is a disputed point, and there does not appear to be sufficient evidence forthcoming to decide it (see A. Müller, Die griechische Bühnenalterthümer, p. 333). There were certainly 12 choreutae in the Persae and Septem (A. Müller, op. cit. 202, note 3), and most probably in the Ajax (Muff, Die chorische Technik des Sophokles. pp. 53, 79); but it remains an undecided question whether there were only 12 in the Agamemnon and Eumeeides, as is the view of Wecklein (Neue Jahrbücher für Philologie, Suppl. xiii. p. 217), who holds that Aeschylus had a chorus of 12 in all his plays, or 15, as is attested by the Scholiasts on Eumen. 586 and on Equites 589, and is maintained by R. Arnoldt (Der Chor im Agamemnon, 65 ff.).

The Satyric chorus appears to have consisted of the same number as the tragic chorus. The CHORUS very scanty evidence on the matter points to 15 (Tzetzes, l.c.; R. Arnoldt, Die chorische Technik des Euripides, 308 ff.).

But the chorus of comedy consisted of 24 (Schol. on Aves, 297). Only half a tragic chorus was given to the comic poet, and the same choreutae had to appear in the three comedies of each Agon (O. Müiller, Eumenides, p. 54).

2. Movements and divisions of the Chorus.

The dramatic chorus, unlike the cyclic, was quadrangular (τετράγωνον σχῆμα, Tzetzes, l.c.), one of the features which it borrowed from the Dorians (Ath. 5.181 c). As Pollux tells us (4.108, 109), the entry of the chorus was called πάροδος, its final departure ἔξοδος or ἄφοδος, its temporary departure μετάστασις, and its return after such departure ἐπιπάροδος. (Examples of the latter due to change of scene in the Eumenides, 307; Ajax, 866; and Alcestis, 872.) The tragic chorus was arranged in ζυγὰ of 3 and στοῖχοι of 4 or 5; the comic chorus in ζυγὰ of 4 and στοῖχοι of 6. The arrangement was said to be κατὰ ζυγὰ or κατὰ στοίχους, according to the depth (Poll. 4.108). The chorus usually entered the orchestra κατὰ στοίχους, by the door at the right of the spectators. It rarely made its entrance otherwise, e. g. on the stage, as in the Eumenides (cf. 5.185), and in the Lysistrata by half the chorus (Schol. on 5.321); or hovering over it, as in the Prometheus (128-283). Other examples in A. Müller, op. cit. pp. 125-127.

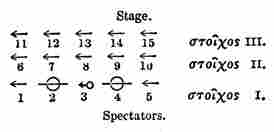

The arrangement of a chorus of 15 at its entrance may be represented thus :

ZZZ.

The members of the row (στοῖχος) next the spectators, viz. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, were called ἀριστεροστάται> (a term retained even when the chorus on very rare occasions, as coming from the country, entered by the door on the left), or πρωτοστάται. Here were the best-looking and most skilled choristers (Schol. in Aristid. p. 535, 18 sqq.), the middle place No. 3 (cf. Photius, s. v. τρίτος ἀριστεροῦ), or No. 2 in a chorus of 12, being occupied by the leader of the chorus, κορυφαῖος; and before and behind him were the παράσταται, subordinate leaders of divisions cf the chorus. The leader, who was also the arranger of the chorus, bore the titles ἡγεμὼν τοῦ χοροῦ, χοροστάτης, χορολέκτης, χοροποιός, and in early times he was the χοραγός. (That all these titles were applied to the leader is shown with great wealth of proof by Sommerbrodt, Scaenica, pp. 12-15.) The members of the third row were called δεξιοστάται or δεξιόστοιχοι or τριτοστάται (Poll. 2.161; 4.106); and those of the second row, which contained the most inferior choristers, were called λαυροστάται, as forming a kind of alley (λαύρα) between the first and third rows. What the ὑποκόλπιον τοῦ χοροῦ was (Photius, s. v.), whether the whole of the second row (Muff, op. cit. p. 5, note 3) or only the middle members of it, viz. 7, 8, 9 (Sommerbrodt, op. cit. [p. 1.421]p. 8), remains disputed. The ψιλεῖς ( “exposed” ), or, as they are occasionally called, κρασπεδῖται ( “fringe men” )--which were the same (Hesych. sub voce ψιλεύει)--were the two extreme ζυγά: viz. 1, 6, 11, and 5, 10, 15.

The entry of the chorus by ζυγὰ was very rare. R. Arnoldt (Die Chorpartieen bei Aristophanes, pp. 35, 186) considers that it was the case in the Acharnians and Ranae. Subjoined is a representation of an entry κατὰ ζυγὰ of a chorus of 15.

ZZZ.

Here 2 is the κορυφαῖος: 1 and 3, the παράσταται: 1, 2, 3, the ἀριστεροστάται: 13, 14, 15, the δεξιοστάται: the three intervening ζυγά, the λαυοοστάται. Rows 1 13 and 3 to 15, the ψιλεῖς or κοασπεδῖται. Either row 2 to 14, or Nos. 5, 8, 11, formed the ὑποκόλπιον τοῦ χοροῦ.

The chorus sometimes did not enter in order at all, but severally (καγ̓ ἕνα or σποράδην); cf. Poll. 4.109. An obvious example is the Oedipus Coloneus, 5.117 foll. (Muff, op. cit. 272.)

When the chorus arrived in the orchestra and had to enter into a dialogue with the actors, they made an evolution, so that the ἀριστεποστάται stood facing the stage. When the stage was not occupied by actors, and specially in the parabasis (see below), the chorous turned round, or perhaps made a regular evolution round (Schol. on Pax, 733) and faced the audience (Proleg. de Comoedia vii. in Schol. in Aristoph. p. xvii., ed. Dübner). They appear to have mounted the stage occasionally, as in the Oedipus Coloneus, 856 (Muff, op. cit. 291); probably in the Helena (19627-1642), the Aves (353-400), &c., if we are not merely to suppose that the chorous stood sufficiently close to the actors to be able to touch them. The chorus sometimes divided into two ἡμιχόρια, each denoted in MSS. by ΗΜΙΧ., which stood opposite one another (χοροὶ ἀντιστοιχοῦντες ἀλλήλοις, Xen. Anab. 5.4, 12). This was very frequent in the strophe and antistrophe of the parabasis. In the chorus of 15 each division was led by a παραστάτης, while the κορυφαῖος superintended the whole; in the chorus of 12, the κορυφαῖος led one division and the παραστάτης the other. Subjoined is a representation of a chorus of 15 divided in two in the most usual way:--

ZZZ.

though no doubt many of the other possible orderly arrangements were often employed. Notwithstanding the statement of Pollux (4.107), there seems to have been a difference between ἡμιχόρια and διχόρια or ἀντιχόρια. The latter is that permanent division of age or sex or rank which is found, for example, in the Lysistrata and the Aves, where the chorus consists of a male and female group (A. Müller, op. cit. p. 219). The Scholiast on the Equites, 589, says that in such cases the more distinguished group, e. g. here the male division, consisted of 13, and the less distinguished of 11; but this is very questionable. There is no certain example of such διχόρια in the extant tragedies, though it has been assumed in the Supplices of Aeschylus and Euripides (R. Arnoldt, Die chorische Technik des Euripides, pp. 72 ff.). But the chorus at times used further to divide into στοῖχοι and ζυγά, and even into individual choristers. A remarkable example of this latter is in the Agamemnon during the murder scene; and it has been suggested that in this and similar cases all the choristers speak each his own distich together, and not one after another (Mahaffy, History of Greek Literature, 1.267). When a chorister had to take the part of an actor, such was called παρασκήνιον, says Pollux (4.109), who however omits the really essential point that, as the name indicates, his part must be spoken, not on the stage but from the side scenes (παρασκήνια). A παρασκήνιον was an example of what is called παραχορήγημα--that is, anything outside what the choregus was strictly bound to supply, but it is especially applied to an additional chorus, as, for example, that of the θεράποντες in the Hippolytus (cf. Sommerbrodt, Scaenica, 173-4).

3. The songs of the Chorus.

As the chorus entered the orchestra, it, or as some say the coryphaeus alone, usually sang the πάροδος, a term like our “march,” applied also to a species of music. Aristotle (Aristot. Poet. 12) defines it as πρώτη λέξις ὅλη τοῦ χοροῦ. It was very frequently in anapaests. The στάσιμα were the regular choral odes which were sung after the chorus had taken up its position on the θυμέλη, and had duly arranged itself. These στάσιμα served to divide the play into acts. They generally consisted of one or more στροφαί, that portion which was sung as the chorus moved from left to right, ἀντιστροφαὶ as it moved from right to left, while the conclusion of the ode was sung standing and called ἐπῳδός (Schol. on Eur. Hec. 647). This of course can only refer to the στάσιμα which was sung by the whole chorus, and not by two half-choruses. That the strophae and antistrophae of all the stasima of Sophocles were sung by half-choruses, while the whole chorus sang the ἐπῳδός, is the view of Muff (op. cit. p. 24 et passim) and Christ (Metrik, 652). The introduction of the strophe, antistrophe, and epode into the original monostrophic chorus is attributed to Stesichorus, though it must be remembered that Alcman had a chorus of fourteen strophes, of which the last seven were in a different metre to the first seven (Grote, ch. 29). The ἐξόδιοι νόμοι or μέλη ἐξόδια (not ἔξοδος, which is the term for the whole of the last act: see Aristot. Poet. 12, and Muff, p. 45) were sung by the chorus, or the coryphaeus, as the chorus moved off the stage to the left of the spectators: like the πάροδος, it was usually in anapaests. A dirge between the chorus and the actors, as in the Choëphoroe (306 ff.) and the [p. 1.422]Electra of Sophocles (121 ff.), was called κομμός (Aristot. l.c.). The dialogue which the MSS. by the heading ΧΟΠ. seem to intimate was held between the actor and the chorus was either sustained on the part of the former by the coryphaeus, or, as seems very probable, the choral parts in κομμοὶ are to be assigned to individual choristers. (See the full discussion in Muff, op. cit. pp. 41, 42.) It is generally said that the dialogue of the coryphaeus with the actor was called καταλογή, while the παρακαταλογὴ was what was delivered by the individual choristers in opposition to μέλος or song of the whole chorus (see B. Arnold, p. 388). But it is more correct to assume that the καταλογὴ were the iambic trimeters which were declaimed by the actors, and the παρακαταλογὴ the trochaic verses which they sang in a kind of recitative with musical accompaniment (see Muff, op. cit. 46; Zielinski, Die Gliederung der altattischen Komüdie, 313).

The parabasis is the distinctive feature of the chorus of the old comedy. In it the chorus, making an evolution and facing the audience, addressed them with remarks on personal matters or on topics of the day (cf. Schol. on Eq. 508; Pax, 733). It consisted of several parts, all of which can be seen in the Aves:--(1) The κομμάτιον (675-683), a short lyrical piece, sung while the chorus was making the evolution to face the audience. (2) The παράβασις proper or ἀνάπαιστοι (684-735), the address of the coryphaeus to the audience, generally in anapaestic tetrameters catalectic (in the Nuibes in Eupolidean metre). The concluding portion of this was called the μακρὸν or πνῖγος (probably 722-735), as it had to be recited in one breath (Hephaest. p. 135; Poll. 4.112). (3) στροφὴ or ᾠδή> (736-751), a short lyrical hymn. (4) ἐπίρρημα (752-767), trochaic tetrameters catalectic, sung in recitative to a musical accompaniment by the coryphaeus. It is a sort of addition to the parabasis proper, and is an address to the people, giving advice, &c. (5) ἀντιστροφὴ or ἀντῳδή (768-782), corresponding to the στροφή. (6) ἀντεπίρρημα (784-799), corresponding to the ἐπίρρημα. In many MSS. of Aristophanes the στροφὴ and ἀντιστροφὴ are assigned each to a semi-chorus; but Müller (op. cit. 219, note 3) does not think much weight is to be attached thereto. Sometimes the separate parts of the parabasis are in different portions of the play, as in the Pax.

4. The dances of the Chorus.

As derived from the dithyramb, of course the chorus danced. The term ὀρχήστρα, and the old name ὀρχησταὶ given to poets, proves this further (Ath. 1.22). But it must be remembered that the term “dance” is to be regarded as equivalent to any “rhythmical movement.” There were three kinds of dances: a special one for each of the different kinds of drama--the grave and stately ἐμμέλεια for tragedy, the frolicsome σίκιννις for the Satyric drama, and the licentious κόρδαξ for comedy (Lucian. de Salt. 26; Bekker, Anecd. p. 101, 16). Aristophanes (see Nubes, 540) does not appear to have used the κόρδαξ. In some cases-as, for example, in the στάσιμα--the dance was generally quite a secondary feature; but there can be no doubt that the chorus danced (i. e. moved rhythmically) while singing the στάσιμα. It is stated in so many words (Aristoph. Thes. 953); and the term στάσιμα means what is sung, not while the chorus remains stationary (Schol. on Eur. Phoen. 202), but what is sung after they had taken up their position in rank and were no longer settling themselves (Hermann, Epist. doctr. metr. § 665). That the contents of many stasima point to the accompaniment of dancing, Muft (op. cit. 33, 34) considers very likely, taking as example the celebrated chorus in the Oedipus Coloneus, 608 ff. Sometimes the coryphaeus sang while the chorus danced. Those entrances and exits which were not regular marches were often accompanied with the dance; and there appears to have been a certain amount of rhythmical movement in the κομμοί (A. Müller, op. cit. p. 222). The dance took a much more prominent position, and a more lively movement was adopted, in the ὑπορχήματα, and in this respect they are distinctly contrasted with the στάσιμα (Schol. on Soph. Trach. 216). Other examples of ὑπορχήματα in Ajax, 693; Oed. Tyr. 1086. It appears that the coryphaeus used to give the first few steps of the dance (ἐνεδίδου τοῖς ἄλλοις τὰ τῆς ὀρχήσεως σχήματα πρῶτος, Dionys. A. R. 7.72). To help the evolutions and dancing of the chorus lines (γραμμαί) were drawn on the thymele to guide them (Hesych. sub voce γραμμαί), just as in the ballet at present. After the Peloponnesian war the art of dancing declined. Carcinus had introduced a kind of very quick ballet which consisted of pirouettes and rapid twirlings of the legs, and this style of dancing became popular (cf. Aristoph. Vesp. ad fin., and Curtius, History of Greece, 4.104). As to the steps and figures of dancing, reference must be made to Chr. Kirchhoff Die orchestische Eurythmie der Griechen, and to the article SALTATIO.

5. The musical accompaniment of the Chorus.

Originally the accompaniment was played on a kind of stringed instrument called κλεψίαμβος (Ath. 14.636; see Muff, op. cit. 47); afterwards by one flute-player (seldom by more than one), playing on a double flute (A. Müller, op. cit. p. 210, note 2). The flute was chosen as the instrument, since it best harmonised with the human voice (Aristot. Prob. 19.43). Dressed in splendid garments and wearing a crown, the flute-player marched before the chorus at their entrances and their exits. During the performance he remained on the thymele or on the steps of the altar (A. Müller, p. 136, note 1). Sometimes there was also the accompaniment of a stringed instrument (Sext. Emp. 751, 17); and both the flute-player and the κιθαριστὴς appear in the great picture of the Satyric chorus from the vase of Ruvo, given by Wieseler (Theatergebaüde und Denkmäler des Bühnenwesens, Taf. vi.), and elaborately discussed by him in Das Satyrspiel; it is also reproduced in Baumeister's Denkmäler, fig. 422. The διαύλιον appears to have been a symphony by the flute-player, the voices not joining in (Hesych. sub voce cf. Schol. on Ran. 1264). When the chorus were to sing or dance, the flute-player gave the signal (διδόναι τὸ ἐνδόσιμον) by pressing with his foot an instrument called κρούπεζα, which was some sort of a wooden rattle (κρόταλον): cf. Poll. 7.87; Hesych. sub voce κρούπεζα. The flute accompaniment of the σίκιννις was called σικιννοτύρβη (Ath. 14.618 c). [p. 1.423]

6. The personnel of the Chorus.

They were always men, citizens, of free birth (Dem. Mid. 532.56), and generally young. Only at the Lenaea were metics allowed to serve in the chorus (Schol. on Plutus, 953). Originally the choreutae served voluntarily (Aristot. Poet. 5), but often in later times pressure had to be put on them by the choregus or chorolectes to make them serve (Antiphon. de Chor. § 11). They were supported by the choregus during the time of training (Argum. ad Antiph. de Chor.), and after the performance he gave them a sumptuous meal (cf. Aristoph. Ach. 1155). They were also paid by the choregus (Xen. Rep. Ath. 1.13), but we do not know the amount. The state granted the choreutae the privilege of exemption from military service (Dem. Mid. 519.15). As there was danger of a fracas often taking place between the choruses of rival choregi, special ἐπιμεληταὶ were appointed by the state to keep order among the choristers (Suidas, s. v. ἐπιμεληταί), though Sommerbrodt (Scaenica, note 3) thinks their function was to see that the choristers did not fall into confusion in making their evolutions.

As to the characters the chorus represented: while the actors were mostly heroes, the chorus represented members of the people, and these of the most various kinds,--old and young, men and women, Greeks and foreigners, even Ocean nymphs in the Prometheus, and inspired Bacchantes in the Bacchae. The chorus of the Satyric drama always represented Satyrs; and in comedy we have all kinds of fantastic forms, such as clouds, frogs, birds, &c.

7. The dress of the Chorus.

They regularly wore masks [PERSONA], in order to appear in similar style to the actors (Theophr. Char. 6; Poll. 4.142). The garments used in tragedy were a short chiton and the himation, though generally special choruses were dressed in character: thus the Eumenides wore black garments and black felt Arcadian hats (Ἀρκαδικὸ πῖλοι: see Suidas, s. v. Φαιός); and the Bacchae wore Bacchic costume. They also appear to have worn a tight-fitting garment (σωμάτιον,) over a certain amount of padding (προστερνίδιον, προγαστρίδιον), and the term σωμάτιον is sometimes applied to this padding (A. Müller, op. cit. p. 230). Sophocles (Vit. Soph. 128, 30) is said to have introduced κρηπῖδες, which had very thin soles. But as they are said to have been worn by actors as well as by the chorus, we cannot be sure that the statement is very reliable, as we know that the actors generally wore cothurni. Perhaps, as Wieseler (op. cit. 11.5) thinks, the subordinate actors used to wear them. Further, the chorus had all sorts of accessories where necessary, such as staves, drums, torches, thyrsi, &c., which they used to lay aside before beginning the dance (Schol. on Pax, 729).

The Satyrs' dress was merely an apron (περίζωμα) of goat-skin round the loins, to which was attached the tail and the phallus, the latter made of red leather; they had besides often a goat's skin round their shoulders. They appeared to be naked, but really they wore a flesh-coloured tight-fitting garment. On their feet they had very thin shoes, though in the pictures they appear to have had bare feet (cf. Wieseler, op. cit. 6.3). On the vase-painting of Ruvo we find one chorister with a short sleeveless tunic, and the χλανὶς ἀνθινή, which is mentioned as a peculiarly Satyric dress (Poll. 4.118).

We have no clear evidence of the costume of the older comedy. It appears to have consisted of the σωμάτιον, χιτών, and ἱμάτιον, the latter being laid aside before dancing (Thesm. 655). The ἱμάτια of the chorus in the Nubes were elaborately adorned (Schol. on Nub. 289). Of course the chorus wore the erect phallus, but this ceased to be worn in the new comedy (A. Müller, p. 257). On their feet they had sandals (σανδαλίσκοι): cf. Aristoph. Frogs 404.

8. Gradual disappearance of the Chorus.

The practice of introducing into tragedies choral odes which had no special relevancy to the play, as was especially done by Agathon, was a sign of the growing feeling that the chorus was not an essential part of the drama. However, we find mention of a tragic chorus in the Demosthenic age (Mid. 533.58), and of a Satyric chorus in the time of Sositheus, 284 B.C. (Anth. Pal. 7.707, 3). But from Delphic inscriptions of 260 B.C. quoted by Wescher and Foucart (Inscript. de Delphes, Nos. 3-6), in which no choreutae appear, these scholars have supposed that the chorus of tragedy had disappeared by that date. The absence of the choral songs and of the chorus as a participator in the action is the external mark which, in a considerable measure, distinguishes the middle and new comedy from the old. The discontinuance of the comic choregia is attributed to a decree of Cinesias (Schol. on Ranae, 153). There were no choregi when Aristophanes produced the Aeolosicon (389 B.C.), and the Plutus (2nd edition). But we must not suppose that the discontinuance of the chorus was sudden, for the chorus sometimes appears even in the middle and new comedy (Boeckh, Staatshaushaltung, i.3 545-6; Meineke, 1.441).

The literature on the subject of the chorus is very extensive. The most important works are: B. Arnold, art. Chor in Baumeister's Denkmäler des klassischen Altertüms, pp. 383-391; Sommerbrodt, Scaenica; Muff, Die chorische Technik des Sophokles; R. Arnoldt, Die chorische Technik des Euripides; F. Castets in Daremberg and Saglio, art. Chorus; A. Müller, Die griechischen Bühnenalterthümer. In the two last works full reference is made to the numerous works on the subject.

2. Roman.

The chorus among the Romans belonged especially to the crepidatae, i.e. the tragedies modelled on and derived from the Greek ones; but it also appears in the national tragedy of the Romans, the praetextatue (see O. Ribbeck, Die römische Tragödie im Zeitalter der Republik, 607, 631 ff.). Even though Diomedes (491, 29, Keil) declares that the Roman comedy had no chorus, yet this is only true generally, for there is an undoubted chorus of fishermen in the Rudens of Plautus. It was probably the whole company of actors (caterva), not a chorus, which said the “Plaudite” with which comedies end (cf. Cic. Sest. 55, 118). There appear to have been choruses in the pantomimus and in the pyrrhica of the empire (Friedländer, Darstellungen, ii.3 434, 443). There was no fixed number of choreutae (Diomedes, l.c.). As that part of the theatre which was the Greek orchestra was given up to the spectators at Rome, the chorus had to occupy the stage (Vitr. 5.6, 2). [p. 1.424]The Roman chorus took more part in the action of the drama than did the Greek chorus (O. Jahn, in Hermes, 2.227: cf. Hor. Ars Poet. 193). It was led by a magister chori, who had his place in the middle of the chorus, and so was called mesochorus (Plin. Ep. 2.14, 6). The musical accompaniment was played by a choraules on a double flute (Diom. l.c.). Between the acts the chorus (probably in tragedy) and the tibicen (in comedy) used to sing or play (Donatus, Arg. ad Andriam); and Horace (Ars Poet. 194) especially urges that the subject of the songs should be pertinent to the action of the drama. The chorus was composed of men who were professionals (artifices), and who were for the most part slaves (Ribbeck, op. cit. 639, 657). As the chorus of the Romans sometimes represented women (e. g. in Ennius's Medea; cf. Cic. Fam. 7.6), they must have worn masks. They were probably dressed after the manner of the Greeks, and the dresses appear to have been very splendid, as was the whole production of plays at the end of the republic and during imperial times; e. g. purple cblamydes were wanted for a chorus of soldiers, as is told in a well-known story (Hor. Ep. 1.6, 40).

Besides B. Arnold (op. cit.), O. Ribbeck (op. cit.), see Gaston Boissier in Daremberg and Saglio, and Friedänder in Mommsen-Marquardt, 6.523.

Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities

| Ancient Greece

Science, Technology , Medicine , Warfare, , Biographies , Life , Cities/Places/Maps , Arts , Literature , Philosophy ,Olympics, Mythology , History , Images Medieval Greece / Byzantine Empire Science, Technology, Arts, , Warfare , Literature, Biographies, Icons, History Modern Greece Cities, Islands, Regions, Fauna/Flora ,Biographies , History , Warfare, Science/Technology, Literature, Music , Arts , Film/Actors , Sport , Fashion --- |