Stefan Lochner

Paintings

Three Saints

Three king altar: St. Ursula and Companions

Three king altar: Adoration of the Magi

Three king altar: St. Gereon and companions

Martyrdom of the Apostles Altarpiece (interior left wing)

Sts Anthony the Hermit, Cornelius and Mary Magdalen with a Donor

Presentation of Christ in the Temple

Triptych with the Virgin and Child in an Enclosed garden

St. Francis receiving the stigmata,

Saint Jerome in his Study cabinet

Drawings

Fine Art Prints | Greeting Cards | Phone Cases | Lifestyle | Face Masks | Men's , Women' Apparel | Home Decor | jigsaw puzzles | Notebooks | Tapestries | ...

Three Saints

Stefan Lochner (The Dombild Master) (c. 1410 – 1451) was a German painter working in the late International Gothic style who produced single panel paintings, triptychs and illuminated manuscripts. His work is known for its clean appearance, virtuoso surface textures and innovative iconography. His paintings combine a Gothic tendency towards long flowing lines in brilliant colours with a Flemish-influenced realism and attention to detail. Lochner's compositions often include fanciful angels, singing and playing musical instruments. He was skilled both as a miniaturist and a painter of monumental works, and seems to have had knowledge of metal work, given his realistic depictions of objects such as the Magi's gifts in the Cologne altarpiece.[1]

Lochner was active in Cologne, and is best known for the Altar of the City Patrons triptych, commissioned for the Town Hall chapel in the 1440s. He was long known by the Dombild Master name of convenience until the 19th century when art historians associated that master's painting with the historical Stefan Lochner. Since then some outlines of his life have been established, and 33 works, dated between the early 1430s and 1451, are attributed with varying degrees of confidence.[2] Due to lack of documentary evidence many attributions remain problematic.[3]

Lochner was one of the last major painters working in the "soft style" (weicher Stil) of the International Gothic tradition. He was one of the most important German painters before Albrecht Dürer; an artist who held Lochner in great esteem. One of Dürer's diary entries was eventually key in establishing Locher's identity.[4]

Stefan Lochner died in the winter of 1450-51 during an outbreak of plague. His work has been praised by Friedrich Schlegel and Goethe for the "sweetness and grace" of his Madonna portraits.[1]

Identity and attribution

The Altarpiece of the City's Patron Saints, or the Dombild Altarpiece. Tempera on oak, 94in x 14in. Cologne Cathedral. The central panel shows the Virgin and child receiving the magi. The left wing has Saint Ursula, accompanied by her husband Eutherus and her companions, 11000 virgins. The right panel contains Saint Gereon presented as a knight holding a flag and cross[5]

There are no signed paintings by Lochner, and his identity was not established until the 19th century. The determination of his identity took place in two stages. Firstly, in an article published in 1823, J. F. Böhmer identified the Altar of the City Patrons with a work mentioned in an account of a visit to Cologne in 1520 in the diary of Albrecht Dürer, during which the notorious thrifty artist paid 5 silver pfennig[6] to see an altarpiece by "Maister Steffan", some seventy years after Lochner's death.[7] Dürer's description matches exactly with the center panel of the Altarpiece of the City's Patron Saints. The altarpiece is referred to in a number of other records. It was repaired and re-gilded in 1568, and mentioned in Georg Braun's "Civitates Orbis Terrarum" in 1572.[8] Unfortunately Dürer fails to mention specifically which of Maister Steffan's panels he saw, giving some rise to speculation.[9]

German Gothic art underwent a revival in the early 19th century Romantic period, when the work was seen as a climax of the late Gothic period. The German philosopher and critic Friedrich Schlegel was instrumental in reviving Lochner's reputation; he wrote lengthy tracts, comparing it favourably to the work of Raphael, and proposing that it exceeded anything by van Eyck, Dürer or Holbein.[10] Later, Goethe was enthusiastic – at length – [11] emphasising Lochner's German "spirit and origin", yet described the Dombild as the "axis around which the ancient Netherlandish art resolves into the new."[12]

Triptych with the Virgin in the Garden of Paradise, c. 1445 – 1450. Wallraf-Richartz-Museum, Cologne

Lochner's identity remained unknown for centuries, and no other known works were associated works with the altarpiece.[11] In 1816 Ferdinand Franz Wallraf identified him as Philipp Kalf, based on a reading of an name inscribed on the sheath of a figure on the right of the center panel. He misinterpreted markings on the stone floor of the "Annunciation" to read 1410, which he took as the year of completion.[13] Later, Johann Dominicus Fiorillo discovered a 15th-century record that read "in 1380 there was an excellent painter in Cologne called Wilhelm, who had no equal in his art and who depicted human beings as if they were alive".[14] In 1850 Johann Jakob Merlo identified "Maister Steffan" with the historical Stefan Lochner.[15]

Based on their stylistic similarity to the Altar of the City Patrons, art historians have attributed other paintings to him, although a number have questioned whether the diary entry was authentically made by Dürer. Documentary evidence linking the paintings and miniatures with the historical Lochner has also been challenged, most notably by Michael Wolfson in 1996.[4] In either case, the extent of his direct hand, as opposed to those of workshop members or followers, is debated.[16] Some panels formerly attributed to him are now thought to date from after 1451, the year of his death.[17]

Life

Early life, and move to Cologne

There are no historical records of Lochner's early life; even if the the loss of local archival records during the French occupation of Cologne are ignored, historical record of people from his supposed birth area reveals little.[18] Through threadbare clues and supposition, mostly centered around a relatively wealthy couple that perished during plague, believed to be his parents, he is thought to have come from Meersburg, near Lake Constance. Georg and Alhet Lochner were citizens and recorded as having died there in 1451. "Stefan" is referred to as "Stefan Lochner of Constance" in two documents dated 1444 and 1448.[19] However, there is no archival evidence that he was there, and his style bears no trace of the art of that region.[20] Recent research has not found any further records of him or his family in the town, although there is mention of Lochner's (a fairly uncommon name) in the village of Hagnau, two kilometers from Meersburg.[19] Lochner's talent was recognised from an early age.[21] He may have been of Netherlandish origin or worked there for a master, possibly Robert Campin. His work seems influenced by Jan van Eyck and Rogier van der Weyden; elements of their styles can be detected in the structure and colourisation of his mature works, especially in his Last Judgment,[22] although neither is thought to be the master under whom he had studied.[23]

Saint John the Evangelist, c 1448–50. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

Mary Magdalen, c 1448–50. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam

Cologne had a long tradition of producing high end visual art, and in the 14th century its output was considered equal to Vienna and Prague. In the 15th century its artists concentrated on more personal, intimate and homely forms, and the area became known for its production of small panels of "great lyrical charm and loveliness, which reflected the deep devotion of the writings of the German mystics".[24] By the 1430s, painting in Cologne had become conventional and somewhat old fashioned, still under the influence of the International courtly style of Master of Saint Veronica, known to have been active until 1420.[25] After his arrival, Lochner, who was earlier exposed to the Netherlandish painters and already working with oil,[26] eclipsed other artistic work in the city.[27] According to art historian Emmy Wellesz, after Lochner's arrival "painting in Cologne became infused with a new life", perhaps enriched by the earlier exposure to the Netherlandish artists.[24] He became widely celebrated as the most capable and modern painter in the city, where he was known as "Maister Steffan".[28]

Lochner's first appearance in extant records in 1442; nine years before he died.[2] He moved to Cologne on receiving a commission from the city council for the provision of decorations for the visit of Emperor Frederick III. Lochner was seemingly a well established and although other artists were involved in preparing for the event, Lochner was responsible for the most important arrangements. The centerpiece seems to have been the Dombild Altarpiece, described by modern art historians as "the most important commission of the fifteenth century in Cologne".[29] He is recorded as having been paid forty marks and ten shillings for his effort.[18]

Success, city councilor

Crucifixion, 1445. Alte Pinakothek, Munich

Lochner bought a house around 1442 with his wife Lysbeth. Nothing else is known about her, and the couple apparently had no children.[18] In 1444 he was able to afford to sell it for two larger properties, one named "zome Carbunckel", near Saint Alban Church,[30] and another called "zome Alden Gryne".[29] Historians have speculated whether the acquisition of larger premises indicates the need to house additional assistants in a larger workshop due to an increase in activity. It is likely that he lived in one house and worked in the other.[29] The purchases may have caused a strain, as around 1447 he seems to have encountered financial difficulties, forcing him to remortgage both. Second mortgages were taken out in 1448.[18]

In 1447 the local painters guild elected Lochner to serve as their representative municipal councilor, or Ratsherr. The appointment implies he had lived in Cologne since at least 1437, as only those who had been living in the city for ten years could take up the position. He seemingly had not taken up citizenship immediately, possibly to avoid paying the 12 guilder fee, and anyway the guild did not require it. However he was obliged to as Ratsherr, and on 24 June 1447 became a burgher of Cologne.[31] The role of municipal councilor could only be held for a one-year term, with two years vacated before reoccupation. Lochner was re-elected for a second term in the winter of 1450, but died in office.[18]

Plague, early death

Germany was undergoing an outbreak of plague in 1451, and there are no surviving records of Lochner after Christmas of that year. On 16 August the council of Meersburg was informed by the council of Cologne that Lochner would not be able to travel to attend to the will and estate of his parents, who had recently died.[19] It is presumed he was by then already ill. Plague was widespread in the area Lochner lived. On 22 September his parish of Saint Alban requested permission to burn victims in the lot next to his house as there was no longer room in the cemetery. Lochner died sometime between this date and January 1452, when a creditor took possession of his house, indicating that he had been unable to pay off his debts, perhaps because he had been ill for some time.[11] The latter record does not mention Lysbeth, who was presumably already dead.[19]

Style

Lochner worked in the courtly, International Gothic style, which was considered by many as dated and old-fashioned by the 1440s.[32] Yet he introduced a number of innovations to painting in Cologne, especially in filling his backgrounds and landscapes with specific details, giving his figures more volume, and representing receding space (perspective).[33] Art historian Emmy Wellesz describes his paintings as sharing an "intensity of feeling which gives a very special and very moving quality to his work. His devotion is reflected in his figures: it charges with symbolic meaning the smallest details of his paintings; and, in a hidden, almost magical way, it speaks from the concord of his pure and glowing colours."[34]

Lochner painted with oil. His colour schemes tend to be bright and luminous, especially his reds, blues and greens. He often employed ultramarine, then an expensive and difficult to source pigment.[35] His figures are regularly outlined with red paint.[36] He was innovative in his rendering of flesh tones, which he built up using lead whites to give pale complexions with almost porcelain qualities. In this he refers to an older tradition of indicating women of high nobility whose paleness was associated with a life spent indoors, "shielded from toiling in the fields, which was the lot of most". In this he follows the Master of Veronica, although the earlier painter's figures had an almost yellowish, ivory hue.[37] His Madonnas tend to be clothed in saturated blues, which resonate with surrounding yellow, red and green paint.[38] James Snyder explains that Lochner "employed these four basic colors for his harmonies", but that he went beyond by using more subdued and deep hues in a technique referred to as "pure color".[39]

Saints Ambroise, Augustin et Cécile with the donor Heynricus Zeuwelgyn, c 1450. Wallraf-Richartz-Museum

Like Conrad von Soest, he often applied black cross-hatching on gold, usually to render metallic objects such as brooches, crowns or buckles, in imitation of the work of goldsmiths on precious objects such as reliquaries and chalices.[40] He was heavily influenced by the art and process of goldsmithing, and evidence of his imitation of elements of their craft, from the contemporary to the ancient, is apparent even in his underdrawings; it has been suggested that he may have once trained as a goldsmith.[41]

He seems to have prepared on paper before he approached underdrawings; there is relatively little evidence of reworking, even when positioning large groups of figures. In the underdrawings for the Last Judgment panels he used letters to denote the final colour to be applied, for example g for gelb (yellow) or w for weiss (white), and there are few deviations in the finished work.[42] He often rearranged drapery fold lines, or enlarged or diminished the size of figures.[43]

Saints Mark, Barbara and Luke, c 1445–50. Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne

Probably influenced by van Eyck, he closely detailed the fall and gradient of light. According to art historian Brigitte Corley, the clothes of "protagonists change their hues in delicate reaction to the influx of light, reds being transformed through a symphony of pink tonalities to a dusty greyish white, greens to a warm pale yellow, and lemon shading through oranges to a saturated red". Lochner employed the notion of supernatural illumination not just from van Eyck, but also from von Soest's Crucifixion where light emanating from Christ dissolves around John's red robe, as yellows rays eventually become white.[35]

Unlike the painters in the Low Countries, Lochner was not so concerned with delineating perspective; his pictures are often set in shallow space, with the backgrounds giving little indication of distance, and dissolving into solid gold. Related to this, often the ancillary figures lack volume in their rendering. For these reasons, and because of his harmonious colour choices, Lochner is usually described as one of the last exponents of the International Gothic. This is not to say his paintings lack contemporary northern sophistication; his arrangements are often innovative.[44] The worlds he paints are hushed, according to Snyder, achieved with the symmetry of subdued use of color and the often repeated stylistic element of circles. Angels form circles around the heavenly figures; the heavenly figures' heads are highly circular and they wear round haloes. According the Snyder the viewer is slowly "drawn into empathy with the revolving forms.[45]

It is difficult to detect any evolution in Lochner's style. Art historians are unsure if his work became progressively more or less influenced by Netherlandish art. Recent dendrochronological examination of attributed works indicate that his development was not linear; suggesting that the more advanced Presentation in the Temple is of 1445, but predates the more Gothic Saints panels now divided between London and Cologne.[46]

Work

Panel paintings

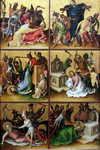

The Martyrdom of the Apostles, 1435-40. Frankfurt, Stadelsches Kunstinstitut

Only two attributed paintings are dated; the 1445 Nativity now in the Alte Pinakothek, Munich, and the larger Presentation in the Temple from 1447, now in Darmstadt.[11] Lochner's major works are three large polyptychs, his Last Judgement, Altarpiece of the City Patron Saints, Nuremberg's Crucifixion and Martyrdom of the Apostles. Like many 15th-century religious pieces, they were broken apart over the centuries, and are today spread across various museums and collections. There are two dated versions of the Presentation in the Temple, one in the Calouste Gulbenkian Museum (1445) and another in the Hessisches Landesmuseum, Darmstadt (1447). There are two surviving wings from an altarpiece with images of saints (now in the National Gallery, London and the Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne).

The Crucifixion is considered one of his earliest works, reminiscent of earlier medieval painting. It has a heavily ornamented gilded background, and the smooth flowing quality of the 'soft' Gothic style. The Last Judgement is probably also from early in his career, but in subject matter and background differs from other extant and attributed works. While the elements are arranged in typical harmony, the composition and tone are unusually dark and dramatic.[44]

Annunciation scene on the reverse of the Altarpiece of the Patron Saints of Cologne, c. 1440–1445, Cologne Cathedral. Outer wing of a triptych altarpiece. Mary receives the word of god, delivered by a dove fluttering over her head.[5]

In later centuries as secular works grew in demand and religious works were seen as constricted and out of step, 15th-century triptychs were often broken up and sold as individual works, especially if a panel or section contained an image that could pass as a secular portrait. Parts of Lochner's Last Judgement are in the Wallraf-Richartz Museum, while other panels from the same work are in the Alte Pinakothek in Munich and the Städel Museum in Frankfurt.[47][48]

His extant works return repeatedly to the same themes. The nativity is recurrent, while several panels depict the Virgin and Child, often surrounded by a chorus of angels and in his earlier panels, blessed by a hovering representation of God or a dove representing the Holy Ghost. In many instances Mary is enclosed in the usual enclosed garden.[34] Several reveal the work of a number of hands, with weaker and less confident passages or scenes attributed to workshop members. The figures of Mary and Gabriel on the reverse of the Dombild were drawn more rapidly and with less skill than the figures on the main panels, and their drapery is modeled with, according to Chapuis, a certain "stiffness", while the cross hatching "achieves no clear definition of relief".[49] A number of drawings have been associated with him, but only one, a c.1450 brush and ink on paper Virgin and Child now in the Musee du Louvre, is attributed with confidence.[50]

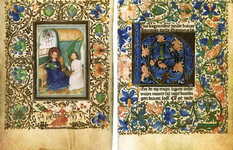

Illuminated manuscript and other formats

Job Derided by his Wife, c 1450

Three surviving books of hours are attributed to him; in Darmstadt, Berlin and Anholt. However the extent of his association is debated; workshop members were probably heavily involved in their production. The most famous is the '"Prayer book of Stephan Lochner" (Gebetbuch des Stephan Lochner) of 1451, now at Darmstadt; the others are the Berlin Book of Prayers dated 1444, and a book in Anholt. The three books are very small (Berlin: 9.3 cm x 7 cm, Darmstadt: 107 cm x 8 cm, Anholt: 9 cm x 8 cm)[51] and are similar in layout, decoration and colourisation; all are extensively decorated with gold and blue. The borders are ornamented in bright colours and contain acanthus scrolls, gold foliage, flowers, berry-like fruits and round pods.[52] The Darmstadt book includes a complete cycle of the Martyrdom of the Apostles. Its illustrations contain his characteristic application of deep blue, reminiscent of his Virgin in the Rose Garden.[53]

Flight into Egypt, 1451. The Virgin sits on a small donkey. Joseph holds the reins, and is depicted as good humoured, but bearded and rather crude.[27]

Art historian Ingo Walther detects Lochner's hand through the "pious intimacy and soulfulness of the figures, always expressed so gently and elegantly, even in the extremely small format of the pictures".[27] Chapuis agrees with the attribution, noting how many of the minaturies share thematic similarities to attributed panels. He writes that the illustrations "are not a peripheral phenomenon. On the contrary, they address several of the concerns articulated in Lochner's paintings and formulate them anew. There is little doubt that these exquisite images stem from the same mind."[54] The text of the Darmstadt book is written in Cologne vernacular, the Berlin book in Latin.[52]

Follower of Stefan Locher, Virgin adoring the infant Christ, pen and black ink on paper. British Museum, 1445

Some art historians have speculated if Lochner worked in other formats. There are extant liturgical vestments that contain embroidered figures, including of St. Barbara, depicted in his style and with similar facial types. This has led to some speculation whether Lochner provided the models. In addition a number of contemporary stained glass panels are similar in style, and there has been debate whether he might have been responsible for church murals; the over-life size figures of the Drombild and Virgin with the Violet indicate his ability to work on a monumental scale.[55]

Two drawings on paper in the British Museum and the Beaux-Arts were at times thought to be studies for the Munich Nativity. The lines of the folding closely match those of the painting, although the technical ability does not. The Paris drawing has blotches of paint indicating that it was a study piece for workshop members. The London piece is superior, but its lines are more rigid, lack Lochner's fluidity, and are considered by hand of a draftsman closely associated with Lochner, but not by him himself.[56]

Influences

Conrad von Soest: St. Dorothea (diptych), c. 1420

Conrad von Soest, St. Odilia. Westphalian State Museum, Münster

His art seems indebted to two broad sources; Netherlandish artists van Eyck and Robert Campin,[33] and the earlier German masters Conrad von Soest and the Master of Saint Veronica.[57] From the former Lochner drew his realism in depicting naturalistic backgrounds, objects and clothes. From the latter he adopted the somewhat antiquated manner of depicting figures, especially females, with doll-like, eloquent and sensitive features, to present "iconic, almost timeless" atmospheres, enhanced by the then old-fashioned gold backgrounds.[3] Lochner's figures have idealised facial features typical of medieval portraiture. His female subjects especially, have usually high foreheads, long noses, small rounded chins, tucked blond curls and prominent ears typical of the late Gothic, giving them the characteristic monumentality of 13th-century art, placing them on seemingly similar shallow backgrounds.[58]

Lochner probably saw van Eyck's c. 1432 Ghent Altarpiece during his visit to the lowlands. He seems to have borrowed a number of motifs and compositional elements; most especially the Ursula and the central Dombild panels quote passages from van Eyck's "Soldiers of Christ". The similarities include the manner in which the figures engage with their space and the emphasis and rendering on elements such as brocades, gems and metals. Some figures in Lochner's paintings are direct quotes from Ghent, and a number of facial features match those seen in van Eyck.[59] His Virgin with the Violet has often been compared to van Eyck's 1439 Virgin at the Fountain.[60] Like van Eyck, Lochner's angels often singor play musical instruments, including lutes and organs.[60]

Yet he seemingly rejected some aspects of van Eyckian realism, notably in his depictions of shadows, and his unwillingness to apply transparent glazes. As a colourist he was more inclined towards the International Gothic style, even if this inhibited realism. He did not use the new Netherlandish techniques of perspective, instead indicated recession through the diminution of parallel objects.[35]

Legacy

Lochner left many followers who painted or drew in his style. Examples in ink after his Virgin in Adoration are in the British Museum and École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts.[56]

Evidence suggests Lochner's paintings were well known and widely copied during his lifetime, and remained popular until the 16th century. Albrecht Dürer knew of him before his stay in Cologne. van der Weyden saw his paintings during his travel to Italy. His Altar of Saint John bears influences from Lochner's Flaying of Bartholomew, especially in the executioner's pose,[61] while his Saint Columba altarpiece includes two motifs from Lochner's Adoration of the Magi triptych; those of the king in the central panel with his back to the viewer, and the girl in the right hand wing holding a basket containing doves.[62][63] Hans Memling similarly was exposed to his work when he traveled south to Italy; and the influence of Lochner's Last Judgement can be seen in the latter's Gdansk altarpiece, where the gates of Heaven are similar, as is the rendering of the blessed.[61]

References

Notes

Borchert, 249

Chapuis, 103

Smith, 427

Corley, 78

Wellesz, 7

Chapuis, 28

Rowlands, 28

Chapuis, 37

Wolfson, 235

Chapuis, 14

Wellesz, 2

Chapuis, 17

Chapuis, 16

"Eodem tempore 1380 Coloniae era pictor optimus, cui non fuit similis in arte sua, dictus fuit Wilhelmus, de pingit enim homines quasi viventes". See Chapuis, 33

Unverfehrt, 107

Chapuis, 261

Chilvers, 366

Chapuis, 26

Chapuis, 27

Borchert, 248

Borchert, 70

Stechow, 312

Borchert, 71

Wellesz, 3

Corley, 80

Nash, 206

Walther, 318

Borchert, 70–71

Chapus, 156

Singer, 16

Chapuis, 26–27

Schmid; Holladay, 491

Emmerson, 412

Wellesz, 6

Corley, 94

Emmerson, 413

Chapuis, 226

Chapuis, 88

Snyder, 219

Chapuis, 214

Chapuis, 217

Chapuis, 119

Chapuis, 148

Wellesz, 4

Snyder, 220

Chapuis, 259

"Magdalen (Left hand wing of the two wings of the "Altarpiece of the Last Judgement" (C. 1445) Stefan Lochner (1410–1451)". Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

"Altarflügel mit den Apostelmartyrien". Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main. 03 September 2014

Chapuis, 130

Borchert, 254

Chapuis, 66

Chapuis, 67

Chapuis, 94-96

Chapuis, 69

Chapuis, 188

Chapuis, 182-84

"Stephan Lochner". National Gallery, London. Retrieved 16 August 2015

Corley, 81–82

Chapuis, 207

Corley, 90

Chapuis, 30–31

Ridderbos et al, 38

Richardson, 89

"Three Saints". National Gallery, London. Retrieved 16 August 2015

Sources

Billinge, Rachel; Campbell, Lorne; Dunkerton, Jill; Foister, Susan. "A double-sided panel by Stephan Lochner". National Gallery Technical Bulletin, No 18, 1997

Borchert, Till-Holger. Van Eyck to Dürer. London: Thames & Hudson, 2011. ISBN 978-0-5002-3883-7

Chapuis, Julien. Stefan Lochner: Image Making in Fifteenth-Century Cologne. Turnhout: Brepols, 2004. ISBN 978-2-5035-0567-1

Chilvers, Ian. The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-1995-3294-0

Corley, Brigitte. "Plausible Provenance for Stefan Lochner?". Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, Volume 59, 1996. 78–96

Emmerson, Richard K. Key Figures in Medieval Europe. London: Routledge, 2005. ISBN 978-0-4159-7385-4

Nash, Susie. Northern Renaissance art. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-1928-4269-5

Richardson, Carol. Locating Renaissance Art: Renaissance Art Reconsidered. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-3001-2188-9

Ridderbos, Bernhard; Van Buren, Anne; Van Veen, Henk. Early Netherlandish Paintings: Rediscovery, Reception and Research. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0-8923-6816-7

Rowlands, John. "The Age of Dürer and Holbein: German Drawings 1400–1550". London: British Museum Publications, 1988. ISBN 978-0-7141-1639-6

Schmid, Wolfgang; Holladay, Joan. "Reviewed: 'Painting and Patronage in Cologne, 1300–1500' by Brigitte Corley". Speculum, Volume 78, No. 2, 2003

Singer, Hans W. "Stories of the German Artists". Wildside Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-4344-0687-3

Smith, Jeffrey Chipps. The Northern Renaissance (Art and Ideas). London: Phaidon Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-7148-3867-0

Snyder, James. Northern Renaissance Art. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1985. ISBN 9780131833487

Stechow, Wolfgang. "A Youthful Work by Stephan Lochner". The Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art, Volume 55, No. 10, 1968. 307–314

Walther, Ingo. Codices Illustres: The World's most famous Illuminated Manuscripts. Berlin: Taschen, 2014. ISBN 978-3-8365-5379-7

Wellesz, Emmy; Rothenstein, John (ed). Stephan Lochner. London: Fratelli Fabbri, 1963

Wolfson, Michael. "Hat Dürer das 'Dombild' gesehen?". Zeitschrift für Kunstgeschichte, Volume 49, 1986. 229–235

Unverfehrt, Gerd. Da sah ich viel köstliche Dinge: Albrecht Dürers Reise in die Niederlande. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2007. ISBN 978-3-5254-7010-7

Further reading

Zehnder, Frank Günter. Stefan Lochner Meister zu Köln Herkunft – Werke – Wirkung. Cologne: Verlag Locher, 1993. ISBN 978-3-9801-8011-5

----

Fine Art Prints | Greeting Cards | Phone Cases | Lifestyle | Face Masks | Men's , Women' Apparel | Home Decor | jigsaw puzzles | Notebooks | Tapestries | ...

----

Artist

A - B - C - D - E - F - G - H - I - J - K - L - M -

N - O - P - Q - R - S - T - U - V - W - X - Y - Z

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/"

All text is available under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License